12. Manifest Destiny

As we have already seen, the differences that led to the secession of the South and the Civil War were present from the start of the United States. Early compromises over the 3/5 provision of the Constitution and banning slavery in the Northwest Territory led to disagreements over issues like the states’ right to nullify federal laws. In this chapter we’ll look more closely at the escalating conflicts between the slaveholding South and the increasingly anti-slavery North and West.

The admission of new states increased focus on the balance between supporters and opponents of slavery in government. In 1820, a bill called the Missouri Compromise allowed two new states to enter the Union simultaneously to keep the balance. Free-soil Maine and slaveholding Missouri would each get two senators and a small number of representatives until their populations increased. An additional clause in the law would prevent slavery north of the 36°30′ parallel, excluding Missouri. President James Monroe signed it on March 6, 1820.

The Missouri Compromise was controversial at the time and many Americans worried that the country had become lawfully divided along sectional lines. Tejanos in northern Mexico were supported by southerners, especially after they achieved a degree of independence from anti-slavery Mexico in 1836. The annexation of Texas into the United States in 1845, which precipitated the Mexican-American War, also triggered another conflict over slave states.

Mexican politics were extremely chaotic, in the eyes of Americans. When the Mexicans rebelled against Spanish rule in the 1810s, the royal government sent a general named Agustín de Iturbide against Vicente Guerrero’s forces, but Guerrero beat Iturbide in battle and then convinced him to join the revolution. In 1821 the two allied under the Plan de Iguala, or the plan of the three guarantees, which again proclaimed Mexico’s independence and declared that “All inhabitants . . . without distinction of their European, African or Indian origins are citizens . . . with full freedom to pursue their livelihoods according to their merits and virtues.” When Iturbide declared himself emperor of Mexico, Guerrero and his supporters rebelled and although Iturbide defeated them in the field he resigned when Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna also rebelled and went into exile. Santa Anna (1794-1876) was a creole general who like Iturbide had first defended New Spain and then switched to the patriot cause. Santa Anna would become Mexico’s 8th president, serving from 1833 to 1855. Mexican politics remained complicated and turbulent: suffice it to say that Santa Anna ended his life living in exile in Cuba and New York after 1855, and both Iturbide and Guerrero ended up being executed in their turns.

Santan Anna was born in 1794 into a wealthy creole family in Veracruz, the port city on the Gulf Coast that had been founded by Cortés in 1519. In 1810 as a sixteen-year old, Santa Anna joined the army against his parents’ wishes and fought revolutionaries like Manuel Hidalgo y Costilla. He was wounded in battle and by age 18 had been promoted to Lieutenant. When royalist officer Agustín Iturbide joined Vicente Guerrero in 1821 to support the revolution, Santa Anna changed sides too. As a reward for driving Spanish forces out of Veracruz, Iturbide made Santa Anna a general.

Santa Anna was given control of the port of Veracruz and was rapidly becoming a regional caudillo. Iturbide removed Santa Anna from the post and in 1822 Santa Anna joined a rebellion against the dictator, when Iturbide suspended the constituent congress. In 1828 Santa Anna supported Guerrero for president. Spain made a final attempt to retake Mexico in 1829 and Santa Anna led the forces that defeated the small Spanish invasion. People began calling him (with his approval) the savior of the motherland and the Napoleon of the West. Later in 1829 a coup led by the vice president deposed and executed Guerrero. Santa Anna commanded the forces opposing the new president. In 1833 he was elected 8th president of Mexico. He would serve 11 non-consecutive terms over the next 22 years.

Santa Anna is often criticized as an opportunist, but American historians may be guilty of demonizing the victim. In October 1835 a small group of Tejanos living in the northern Mexican territory of Texas rebelled against the central government and declared their independence. The Tejanos were Americans who had migrated from Southern states along with their slaves, and they refused to free their slaves in direct violation of Mexican law (Mexico had eliminated slavery in its 1824 Constitution and by 1829 slavery was completely ended throughout Mexico). The Tejanos insisted their slaves were actually “indentured servants for life.” The Tejanos and supporters from the US attacked and defeated Mexican army garrisons in the territory. President Santa Anna declared that any foreigners fighting Mexican troops “will be deemed pirates and dealt with as such, being citizens of no nation presently at war with the Republic and fighting under no recognized flag.” Having declared the rebels outlaws (since the US government remained silent on the issue), Santa Anna led an army to personally retake Texas. The Tejanos fortified an old Mission called the Alamo and Santa Anna overran it and killed them all.

A new Tejano force under Sam Houston managed to capture Santa Anna in a later battle and held him hostage until he agreed to withdraw the army to the Rio Grande. Mexico never recognized the independence of Texas, and when the US annexed it in 1845 and immediately made it the 28th state (without the standard period as a territory) – in a special effort to shore up slavery in the US. Texas entered as a slave state to retain the balance of power between slave and free representatives in Congress and the Senate. In preparation for the annexation, US President James K. Polk made an offer to the Mexican government to purchase the Mexican land between the Republic of Texas and the Rio Grande. The $25 million offer also covered the purchase of Mexico’s western province, Alta California. When the Mexican government (Santa Anna was not president at the time) refused the offer, Polk sent General Zachary Taylor into the Mexican territory. The Mexican army attacked Taylor’s force, killing 12 and capturing 52. Polk cited this attack as an invasion of US territory (even though it was clearly Mexican territory) and asked Congress to declare war.

There are three basic themes to manifest destiny: The special virtues of the American people and their institutions, the mission of the United States to redeem and remake the west in the image of agrarian America, and an irresistible destiny to accomplish this essential duty. Newspaper editor John O’Sullivan is generally credited with coining the term manifest destiny in 1845 to describe the essence of this mindset, but the unsigned editorial titled “Annexation” in which it first appeared was probably written by journalist and annexation advocate Jane Cazneau. The term was used by Democrats in the 1840s to justify the war with Mexico and it was also used to divide half of Oregon with the United Kingdom. But some historians suggest that although it captured the imagination of the people, manifest destiny never became a national political priority. By 1843, former U.S. President John Quincy Adams, originally a major supporter of the concept underlying manifest destiny, had changed his mind and repudiated expansionism because it meant the expansion of slavery in Texas.

Cazneau was sent by President Polk on a secret peace mission to Mexico in 1845. Instead of waiting for more comfortable transportation, she rode there on horseback. With the outbreak of the Mexican-American War, she went to the front, where she witnessed Winfield Scott’s capture of the fortress of Vera Cruz in March 1847, the first female war correspondent in American history, using the name of “Cora Montgomery.” She helped negotiate the Treaty of Guadalupe-Hidalgo (1848), which included guarantees of property rights to both male and female nonresident landowners. While in Mexico, she worked on canal-building expeditions and banking projects. At the end of the Mexican-American War she turned her attention to Cuba, and the potential it represented, advocating its annexation, and denouncing its Spanish colonial overlords.

In 1845, Texas became a US State, adopting a constitution that specifically endorsed both slavery and the slave trade (which was illegal in the US). The US assumed the territorial claims of the Texas Republic, which included a large disputed territory extending to the Rio Grande. President James K. Polk offered to buy the disputed territory as well as “Alta California” for $25 million, but Mexico refused. Polk moved US troops led by General (later president) Zachary Taylor into the area, and the Mexicans attacked a patrol. This led to both nations declaring war on each other.

The Mexican American War was almost entirely fought in Mexico, and was basically a US invasion of Mexico. Santa Anna, who was not president when the war began, was reelected to lead the nation and the army. The US landed its forces at Veracruz and fought their way to Mexico City, which they conquered and occupied. The 1848 Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo ended the war and forced the Mexican renunciation of its claim on the Texas territory and cession of its northern territories in exchange for a $15 million payment for physical damage caused by the war. Mexico lost half of its national territory and the US acquired a region that became the states of New Mexico, Arizona, Nevada, California, Utah, Colorado, and parts of Wyoming, Kansas, and Oklahoma.

Although most Americans supported the war and believed it represented the Manifest Destiny of the US to occupy the entire continent, some opposed it. Abraham Lincoln and black abolitionist Frederick Douglass both wrote against the war, and Henry David Thoreau spent time in jail and wrote his famous essay Civil Disobedience about his refusal to pay taxes to support the war. Even General and later President Ulysses S. Grant (who had been a lieutenant under General Taylor) recalled in his memoirs “I was bitterly opposed to the measure, and to this day regard the war which resulted as one of the most unjust ever waged by a stronger against a weaker nation. It was an instance of a republic following the bad example of European monarchies, in not considering justice in their desire to acquire additional territory.”

Congressman David Wilmot introduced an amendment called the Wilmot Proviso in August 1846 on a $2,000,000 appropriations bill intended for the final negotiations to resolve the war Americans believed would be over quickly. Wilmot’s rider would have banned slavery in all the territory the US acquired from Mexico. The appropriations bill with the Wilmot Proviso attached passed the House of Representatives but the Senate adjourned rather than debate it. It was reintroduced in February 1847 and again passed the House and failed in the Senate. In 1848, an attempt to make it part of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo also failed. Sectional political disputes over slavery in the Southwest continued until the Compromise of 1850.

Antislavery northerners clung to the idea expressed in the 1846 Wilmot Proviso: slavery would not expand into the areas taken from Mexico. Though the proviso remained a proposal and never became a law, it defined the sectional division. The Free-Soil Party, which formed at the conclusion of the Mexican-American War in 1848 and included many members of the abolitionist Liberty Party, made this position the centerpiece of all its political activities, ensuring that the issue of slavery and its expansion remained at the front and center of American political debate. Supporters of the Wilmot Proviso and members of the new Free-Soil Party did not plan to abolish slavery in the states where it already existed, but Free-Soil advocates demanded that the western territories be kept free of slavery for the benefit of white settlers. They wanted to protect white workers from having to compete with slave labor in the West (Abolitionists, in contrast, looked to destroy slavery everywhere in the United States). Southern extremists, especially wealthy slaveholders, reacted with outrage at this effort to limit slavery’s expansion. They argued for the right to bring their slave property west, and they vowed to leave the Union if necessary to protect their way of life and ensure that the American empire of slavery would continue to grow.

The issue of what to do with the western territories added to the republic by the Mexican Cession consumed Congress in 1850. The border between Texas and New Mexico remained contested and the issue of California had not been resolved. California was the crown jewel of the Mexican Cession, and following the discovery of gold, it was flush with thousands of immigrants. By most estimates, however, it would be a free state, since the Mexican ban on slavery remained in force and slavery had not taken root in California.

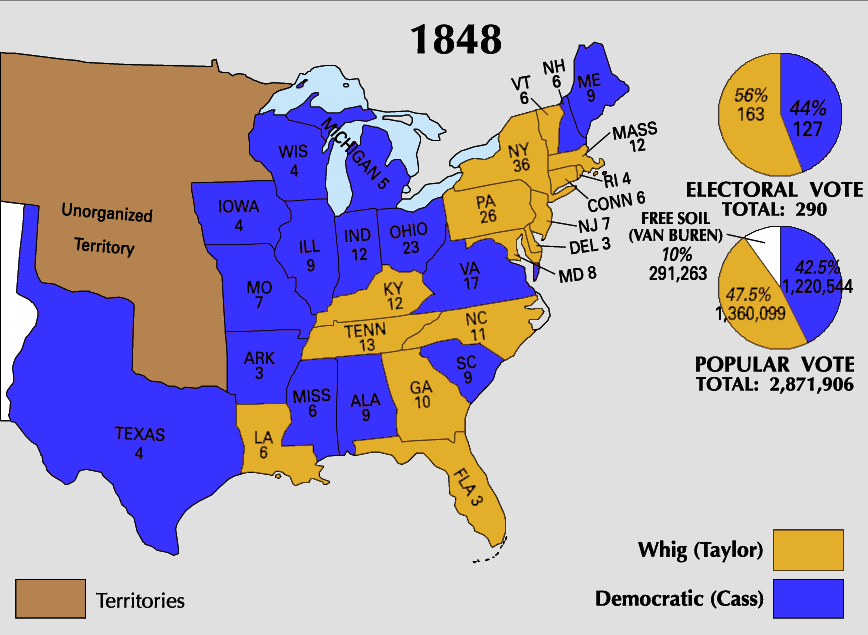

The presidential election of 1848 did little to solve the problems resulting from the Mexican Cession. The Democrats nominated Lewis Cass of Michigan, a supporter of popular sovereignty, or letting the people in the territories decide whether or not to permit slavery based on majority rule. The Whigs nominated General Zachary Taylor, a slaveholder who had achieved national prominence in the Mexican-American War. The fledgling Free-Soil Party put forward former president Martin Van Buren as their candidate. The Free-Soil Party attracted northern Democrats who supported the Wilmot Proviso, northern Whigs who rejected Taylor because he was a slaveholder, former members of the Liberty Party, and other abolitionists. The Free-Soil Party took votes away from Whigs and Democrats and helped to ensure Taylor’s election in 1848.

As president, Taylor sought to defuse the sectional controversy and preserve the Union. However, the California Gold Rush made California’s statehood into an issue demanding immediate attention. In 1849 California residents adopted a state constitution prohibiting slavery and President Taylor called on Congress to admit California and New Mexico as free states, a move that infuriated southern defenders of slavery. Taylor did not believe slavery could flourish in the arid lands of the Mexican Cession and proposed that the Wilmot Proviso be applied to the entire area. In Congress, Kentucky senator Henry Clay offered a series of resolutions addressing slavery and its expansion. Clay’s resolutions called for the admission of California as a free state; no restrictions on slavery in the rest of the Mexican Cession; a boundary between New Mexico and Texas that did not expand Texas; payment of outstanding Texas debts from the Lone Star Republic days; and the end of the slave trade but continuation of slavery in the nation’s capital; and a more robust federal fugitive slave law. Clay presented these proposals as an omnibus bill, that is, one that would be voted on its totality.

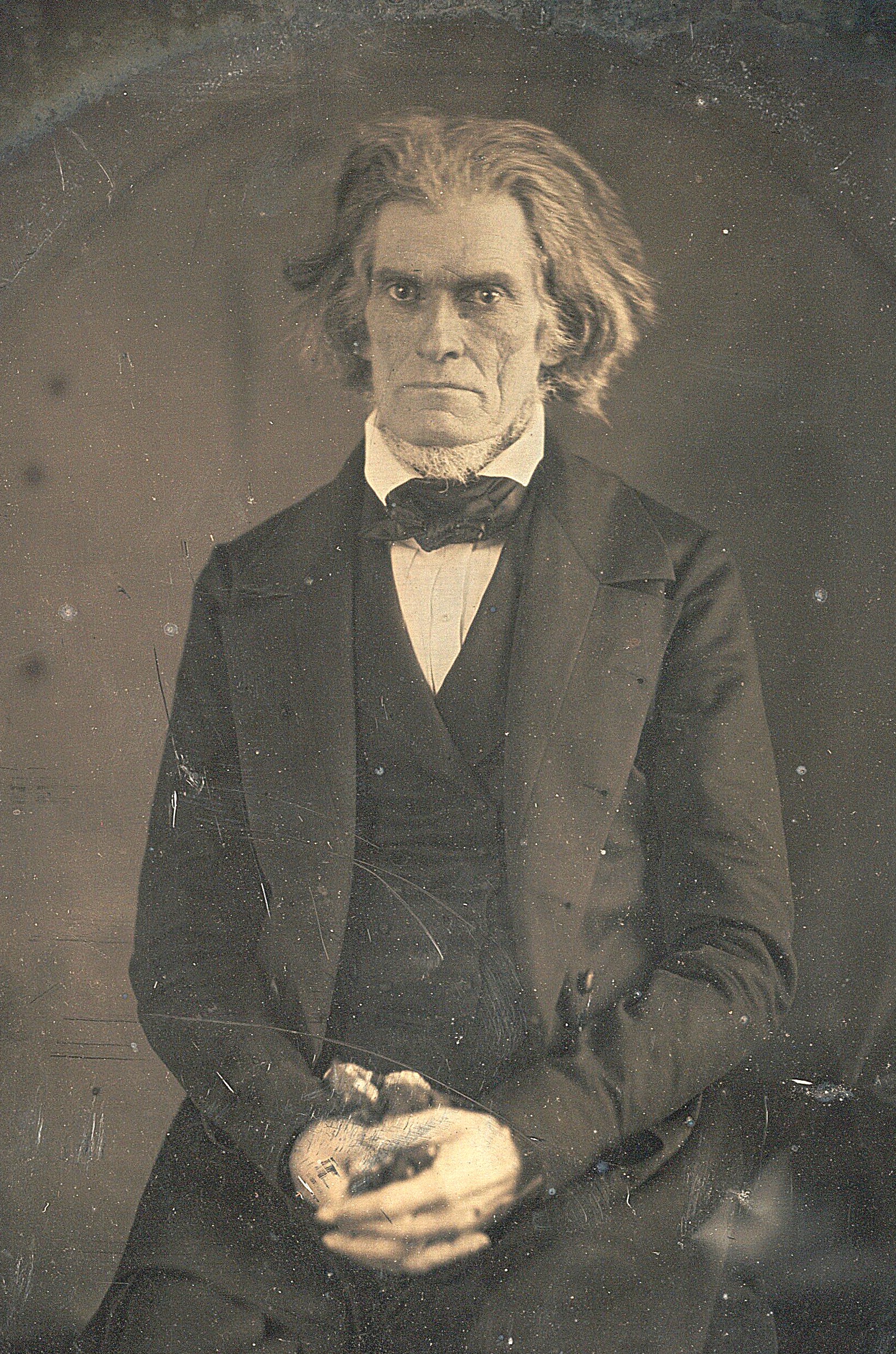

Clay’s proposals ignited angry debate that lasted eight months. Admitting California as a free state aroused the wrath of the aged and deathly ill John C. Calhoun, who had his friend Virginia senator James Mason present his assessment of Clay’s resolutions and the current state of sectional strife. Calhoun called for a vigorous federal law to ensure that runaway slaves were returned to their masters. He also proposed a constitutional amendment specifying a dual presidency—one office that would represent the South and another for the North. Calhoun’s argument portrayed an embattled South faced with continued northern aggression. Massachusetts senator Daniel Webster countered Calhoun and called for national unity, famously declaring that he spoke “not as a Massachusetts man, not as a Northern man, but as an American.” Webster asked southerners to end threats of disunion and requested that the North stop antagonizing the South by harping on the Wilmot Proviso. Like Calhoun, Webster also called for a new federal law to ensure the return of runaway slaves.

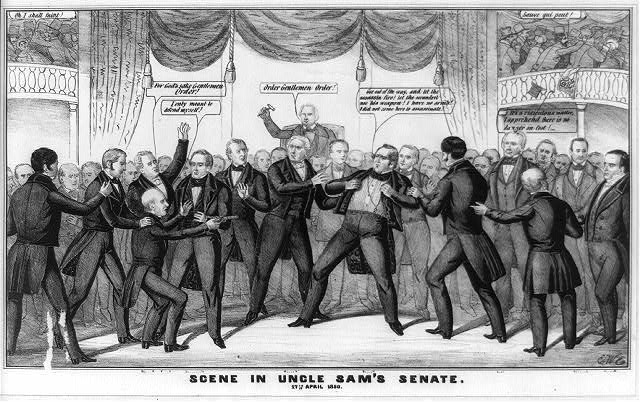

Webster’s efforts to compromise led many abolitionists to denounce him as a traitor. Whig senator William H. Seward of New York declared that slavery—which he characterized as incompatible with the assertion in the Declaration of Independence that “all men are created equal”—would one day be extinguished in the United States. Seward’s speech invoked the idea of a higher moral law than the Constitution and secured his reputation in the Senate as an advocate of abolition. The American public followed the debates with great interest in newspapers. Colorful reports of wrangling in Congress further piqued public interest. It was not uncommon for arguments to devolve into fistfights or duels. One of the most astonishing episodes of the debate occurred in April 1850, when a quarrel erupted between Missouri Democratic senator Thomas Hart Benton and Mississippi Democratic senator Henry S. Foote. When the burly Benton advanced to assault Foote, the Mississippi senator drew his pistol.

President Taylor resented Henry Clay and disapproved of his resolutions. With neither side willing to budge, the government stalled on how to resolve the disposition of the Mexican Cession and the other issues of slavery. The drama only increased when in July 1850, when President Taylor abruptly died and Vice President Millard Fillmore became president. Unlike his predecessor, Fillmore worked with Congress to achieve a solution to the crisis of 1850. Clay stepped down as leader of the compromise effort and Illinois senator Stephen Douglas pushed five separate bills through Congress, collectively composing the Compromise of 1850. First, as advocated by the South, Congress passed the Fugitive Slave Act, a law that provided for payment of federal “bounties” to slave-catchers. Second, to balance this concession to the South, Congress admitted California as a free state, a move that cheered antislavery advocates and abolitionists in the North. Third, Congress settled the contested boundary between New Mexico and Texas and the federal government paid the debts Texas had incurred as an independent republic. Fourth, antislavery advocates welcomed Congress’s ban on the slave trade in Washington, DC, although slavery continued to thrive in the nation’s capital. Finally, on the thorny issue of whether slavery would expand into the territories, Congress avoided making a direct decision and instead relied on the principle of popular sovereignty, allowing majorities in each territory to decide the territory’s laws. The compromise, however, further exposed the sectional divide as votes on the bills divided along strict regional lines.

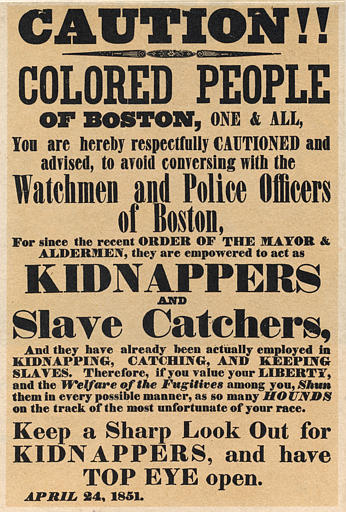

The hope that the Compromise of 1850 would resolve the sectional crisis proved short-lived when the Fugitive Slave Act turned into a major source of conflict. The federal law imposed heavy fines and prison sentences on people in the North and West who aided runaway slaves or refused to join posses to catch fugitives. Many northerners felt the law forced them to act as slave-catchers against their will. The law also established a new group of federal commissioners who would decide the fate of fugitives brought before them. In some instances, slave-catchers even brought in free northern blacks, prompting abolitionist societies to step up their efforts to prevent kidnappings. The commissioners had a financial incentive to send fugitives and free blacks to the slaveholding South, since they received ten dollars for every captive sent South and only five if they decided the person captured was actually free. The commissioners used no juries, and the alleged runaways could not testify in their own defense.

The law alarmed northerners and confirmed the existence of a “Slave Power” of elite slaveholders who wielded power over the federal government, shaping domestic and foreign policies to suit their interests. Despite southerners’ insistence on states’ rights, the Fugitive Slave Act showed that slaveholders were willing to use the power of the federal government to bend people in other states to their will. Although paranoid that federal power would restrict the expansion of slavery, southerners turned to the federal government to protect and promote the institution of slavery.

The actual number of slaves who were not captured within a year of escaping remained very low, perhaps no more than one thousand per year in the early 1850s. But southerners feared the influence of the Underground Railroad, a network of northern whites and free blacks who provided safe houses and secret escape routes from the South. Quakers were especially active in this network and historians believe that up to 100,000 slaves used the Underground Railroad. Many thousands of fugitives escaped the United States completely by going to southern Ontario, Canada.

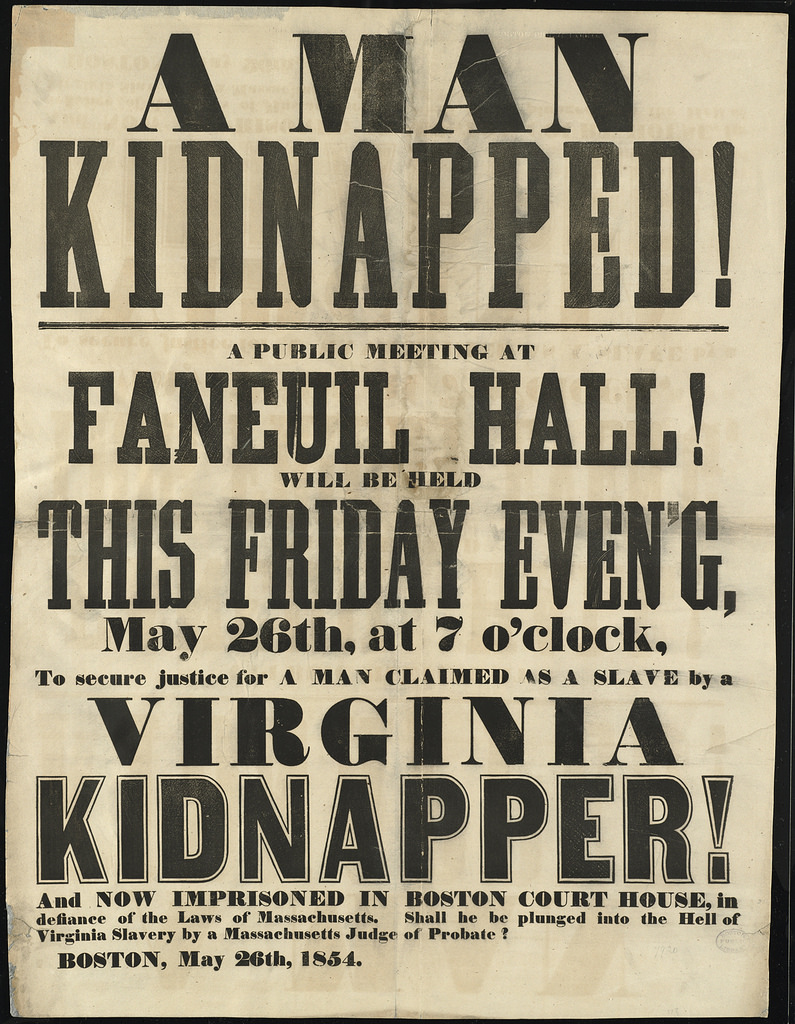

Some abolitionists, such as Frederick Douglass, believed that standing up against the Fugitive Slave Act necessitated violence. In Boston and elsewhere, abolitionists tried to protect fugitives from federal authorities. One case involved Anthony Burns, who had escaped slavery in Virginia in 1853 and made his way to Boston. When federal officials arrested Burns in 1854, abolitionists staged a series of mass demonstrations and a confrontation at the courthouse. Despite their best efforts, however, Burns was returned to Virginia when President Franklin Pierce supported the Fugitive Slave Act with federal troops. Boston abolitionists eventually bought Burns’s freedom. For many northerners, however, the Burns incident, combined with Pierce’s response, only amplified their sense of a conspiracy of southern power.

The backlash against the Fugitive Slave Act, fueled by Uncle Tom’s Cabin and well-publicized cases like that of Anthony Burns, resulted in personal liberty laws being passed in eight northern states declaring that the state would provide legal protection to anyone arrested as a fugitive slave, including the right to trial by jury. The personal liberty laws demonstrated the North’s use of states’ rights in opposition to federal power but furthered southerner claims that northerners had no respect for the Fugitive Slave Act or slaveholders’ property rights.