6 First Expedition to Kansas and Nebraska (1540)

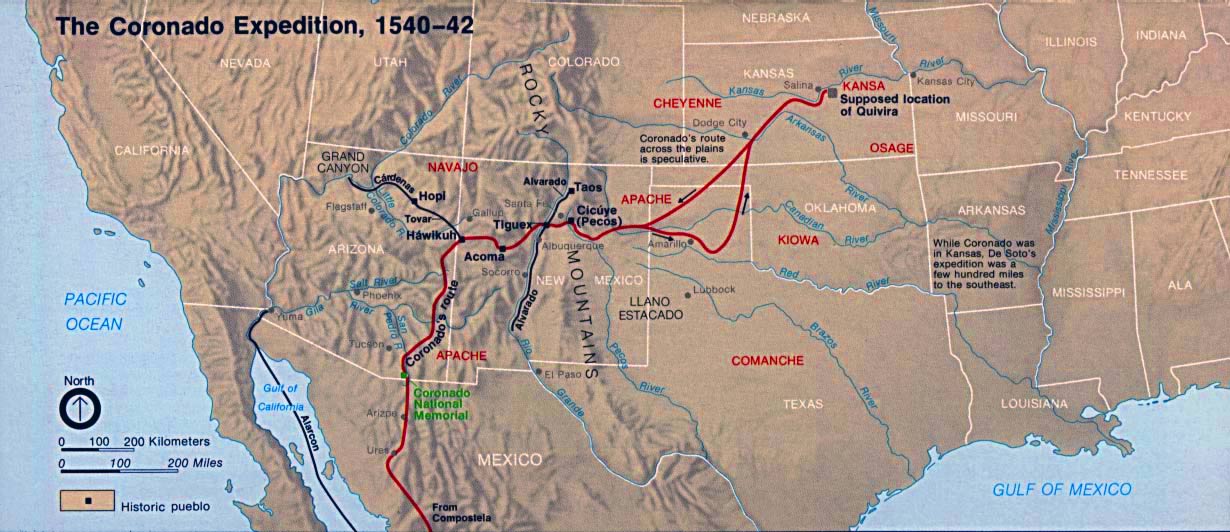

In 1540, Francisco Vásquez de Coronado set out to find the legendary seven cities of Cibola, where he hoped to discover another cache of gold like that of Mexico or Peru. He traveled north from Mexico, through what is now Arizona, New Mexico, Texas, Oklahoma, and Kansas; failing to find the legendary cities but reaching Quivira on the Arkansas River. Jaramillo mentions buffalo herds several times, calling them “cows”. I have replaced the generic term “cows” with buffalo, and retained the word cows only when he is referring to females. When he refers to the “north sea” he is talking about the Atlantic Ocean; the “south sea” is the Pacific.

From here we went to another river, which we called the Bermejo or Red River, in two days’ journey in the same direction, but less toward the northeast. Here we saw an Indian or two, who afterwards turned out to be from the first settlement of Cibola. From here we came in two days’ journey to the said village, the first of Cibola. The houses have flat roofs and walls of stone and mud, and here was where they killed Steve, or Estevanillo, the negro who had come with Dorantes from Florida and returned with Friar Marcos de Niza. In this province of Cibola there are five little villages besides this, all with flat roofs and of stone and mud as I described. The country is cold, as is shown by the houses and hothouses (estufas) they have. From this first village of Cibola, facing the northeast and a little less, on the left hand, there is a province called Tucayan about five days off, which has seven flat-roofed villages with as good as or better food supply than these and even a larger population. And they also have the skins of buffalo and of deer and cloaks of cotton, as I said.

All the waterways we found up to this Cibola, — and I don’t know but what a day or two beyond, — the rivers and streams, run into the south sea [Pacific], and those from beyond here into the North Sea [Atlantic Ocean, specifically the Gulf of Mexico].

From this first village of Cibola, as I have said, we went to another in this same province which was about a short day’s journey off on the way to Tihuex [Rio Grande]. It is nine days of such marches as we have made from this settlement of Cibola to the river of Tihuex. Half-way between, I do not know but it may be a day more or less, is a village of earth and dressed stone in a very strong position which is called Tutahaco. All these Indians except the first in the village of Cibola received us well. At the river of Tihuex there are 15 villages within a distance of about 20 leagues, all with flat-roofed houses of earth and not stone, after the fashion of mud walls. There are other villages besides these on other streams which flow into this and three of these are, for Indians, well worth seeing. All the rest, and these also, have corn and beans and melons, skins and some long robes of feathers which they braid, joining the feathers with a sort of thread. And they also make them of a sort of plain weaving with which they make the cloaks with which they protect themselves. They all have hot rooms underground which, although not very clean, are very warm. They raise and have a very little cotton, of which they make the cloaks of which I have spoken above. This river comes from the northwest and flows about southeast, which shows that it certainly flows into the North Sea.

From Cicuique we came to another river [Pecos?] which the Spaniards named Cicuique, in three days . . . and began to enter the plains where the buffalo are, although we did not find them for some four or five days. After which we began to come across bulls, of which there are great numbers. And after going on and meeting the bulls for two or three days in the same direction, after this we began to find ourselves in the midst of very great numbers of cows, yearlings, and bulls all in together. We found Indians among these first buffalo who were called on this account, by those in the flat-roofed houses, Querechos. They live without houses but have some sets of poles which they carry with them to make something like huts in the places where they stop, which serve them for houses. They tie these poles together at the top and stick the bottoms into the ground, covering them with some buffalo skins which they carry around and which, as I have said, serve them for houses. From what was learned of these Indians, all their human needs are supplied by these buffalo, for they are fed and clothed and shod from these. They are a people who go around here and there, wherever seems to them best.

Here there was a river with more water and more inhabitants than the others. Being asked if there was anything beyond, they said that there was nothing more of Quivira but that there was Harahey, and that it was the same sort of a place with settlements like these and of about the same size. The general sent to summon the lord of those parts and the other Indians whom they said resided in Harahey and he came with about 200 men — all naked — with bows and I don’t know what sort of things on their heads. . . . He was a big Indian, with a large body and limbs and well proportioned. After he had got the opinion of one and another about it, the general asked them what we ought to do, reminding us of how the army had been left and that the rest of us were there, so that it seemed to all of us that as it was already almost the opening of winter. For if I remember rightly, it was after the middle of August, and because there was little to winter there for, and we were but very little prepared for it, and the uncertainty as to the success of the army that had been left, and because the winter might close the roads with snow and rivers which we could not cross, and also in order to see what had happened to the rest of the force left behind, it seemed to us all that his grace ought to go back in search of them. And when he had found out for certain how they were, to winter there and return to that country at the opening of spring, to conquer and cultivate it. Since as I said, this was the last point which we reached, here the Turk [their native guide] saw that he had lied to us and called upon all these people to attack us one night and kill us. We learned of it and put him under guard and strangled him that night, so that he never waked up. With the plan mentioned, we turned back it may have been two or three days, where we provided ourselves with picked fruit and dried corn for our return. The general raised a cross at this place, at the foot of which he made some letters with a chisel which said that “Francisco Vazquez de Coronado,” general of that army, had arrived here.

This country presents a very fine appearance, than which I have not seen a better in all our Spain nor Italy nor a part of France; nor indeed in the other countries in which I have travelled in His Majesty’s service. For it is not a very rough country but is made up of hillocks and plains and very fine appearing rivers and streams, which certainly satisfied me and made me sure that it will be very fruitful in all sorts of products. Indeed there is profit in the buffalo ready to the hand, from the quantity of them, which is as great as one could imagine. We found a variety of Castilian prunes which are not all red, but some of them black and green. The tree and fruit is certainly like that of Castile with a very excellent flavor. Among the buffalo we found flax which springs up from the earth in clumps apart from each other, which are noticeable as the buffalo do not eat it, with their tops and blue flowers and very perfect although small, resembling that of our own Spain. There are grapes along some streams of a fair flavor, not to be improved upon . . .

Source: “First Expedition to Kansas and Nebraska” (1540), Captain Juan Jaramillo

(Translated by George P. Winship, 1896), American History Told by Contemporaries, Albert Bushnell Hart, 1897, 60-4. https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.45493/page/n79/mode/2up