166 Danger of Disunion (1850)

I have, Senators, believed from the first that the agitation of the subject of slavery would if not prevented by some timely and effective measure, end in disunion. Entertaining this opinion, I have on all proper occasions endeavored to call the attention of each of the two great parties which divide the country to adopt some measure to prevent so great a disaster; but without success. The agitation has been permitted to proceed with almost no attempt to resist it, until it has reached a period when it can no longer be disguised or denied that the Union is in danger. You have thus had forced upon you the greatest and the gravest question that can ever come under your consideration. How can the Union be preserved?

The first question then is what is it that has endangered the Union? One of the causes is undoubtedly to be traced to the long-continued agitation of the slave question on the part of the North and the many aggressions which they have made on the rights of the South during the time. There is another, lying back of it, with which this is intimately connected that may be regarded as the great and primary cause. That is to be found in the fact that the equilibrium between the two sections in the government, as it stood when the constitution was ratified and the government put in action, has been destroyed.

To sum up the whole, the United States since they declared their independence have acquired 2,373,046 square miles of territory from which the North will have excluded the South, if she should succeed in monopolizing the newly acquired territories, from about three-fourths of the whole, leaving to the South but about one-fourth. Such is the first and great cause that has destroyed the equilibrium between the two sections in the government. But while these measures were destroying the equilibrium between the two sections, the action of the government was leading to a radical change in its character by concentrating all the power of the system in itself.

That the government claims and practically maintains the right to decide in the last resort as to the extent of its powers will scarcely be denied by anyone conversant with the political history of the country. The character of the government has been changed in consequence from a Federal Republic, as it originally came from the hands of its framers, into a great national consolidated Democracy. It has indeed at present all the characteristics of the latter and not one of the former, although it still retains its outward form. The result of the whole of these causes combined is that the North has acquired a decided ascendency over every department of this government and through it a control over all the powers of the system.

As the North has the absolute control over the government, it is manifest that on all questions between it and the South where there is a diversity of interests the interests of the latter will be sacrificed to the former, however oppressive the effects may be, as the South possesses no means by which it can resist through the action of the government. If there was no question of vital importance to the South in reference to which there was a diversity of views between the two sections, this state of things might be endured without the hazard of destruction to the South. But such is not the fact. There is a question of vital importance to the Southern section, in reference to which the views and feelings of the two sections are as opposite and hostile as they can possibly be. I refer to the relation between the two races in the Southern section, which constitutes a vital portion of her social organization. Every portion of the North entertains views and feelings more or less hostile to it. On the contrary, the Southern section regards the relation as one which cannot be destroyed without subjecting the two races to the greatest calamity and the section to poverty, desolation, and wretchedness. And accordingly they feel bound by every consideration of interest and safety to defend it.

This hostile feeling on the part of the North towards the social organization of the South long lay dormant but it only required some cause to act on those who felt most intensely that they were responsible for its continuance, to call it into action. The increasing power of this government and the control of the Northern section over all its departments furnished the cause. It was this which made an impression on the minds of many that there was little or no restraint to prevent the government from doing whatever it might choose to do. This was sufficient of itself to put the most fanatical portion of the North in action for the purpose of destroying the existing relation between the two races in the South.

Such is a brief history of the agitation, as far as it has yet advanced. Now I ask Senators, what is there to prevent its further progress until it fulfills the ultimate end proposed, unless some decisive measure should be adopted to prevent it? Has any one of the causes which has added to its increase from its original small and contemptible beginning until it has attained its present magnitude, diminished in force? Is the original cause of the movement, that slavery is a sin and ought to be suppressed, weaker now than at the commencement? Or is the Abolition party less numerous or influential, or have they less influence over or control over the two great parties of the North in elections? Or has the South greater means of influencing or controlling the movements of this government now than it had when the agitation commenced? To all these questions but one answer can be given: no, no, no! The very reverse is true. Instead of being weaker, all the elements in favor of agitation are stronger now than they were in 1835 when it first commenced, while all the elements of influence on the part of the South are weaker. Unless something decisive is done, I again ask what is to stop this agitation before the great and final object at which it aims — the abolition of slavery in the states — is consummated? Is it then not certain that if something decisive is not now done to arrest it, the South will be forced to choose between abolition and secession?

I return to the question with which I commenced. How can the Union be saved? There is but one way by which it can with any certainty and that is by a full and final settlement on the principle of justice of all the questions at issue between the two sections. The South asks for justice, simple justice, and less she ought not to take. She has no compromise to offer but the Constitution and no concession or surrender to make. She has already surrendered so much that she has little left to surrender. Such a settlement would go to the root of the evil and remove all cause of discontent, by satisfying the South she could remain honorably and safely in the Union and thereby restore the harmony and fraternal feelings between the sections which existed anterior to the Missouri agitation. Nothing else can with any certainty finally and forever settle the questions at issue. Terminate agitation and save the Union.

But can this be done? Yes, easily. Not by the weaker party, for it can of itself do nothing — not even protect itself — but by the stronger. The North has only to will it to accomplish it, to do justice by conceding to the South an equal right in the acquired territory. And to do her duty by causing the stipulations relative to fugitive slaves to be faithfully fulfilled. To cease the agitation of the slave question and to provide for the insertion of a provision in the Constitution by an amendment which will restore to the South in substance the power she possessed of protecting herself before the equilibrium between the sections was destroyed by the action of this government. There will be no difficulty in devising such a provision — one that will protect the South and which at the same time will improve and strengthen the government instead of impairing and weakening it.

But will the North agree to do this? It is for her to answer this question. If you remain silent, you will compel us to infer by your acts what you intend. In that case, California will become the test question. If you admit her under all the difficulties that oppose her admission, you compel us to infer that you intend to exclude us from the whole of the acquired territories.

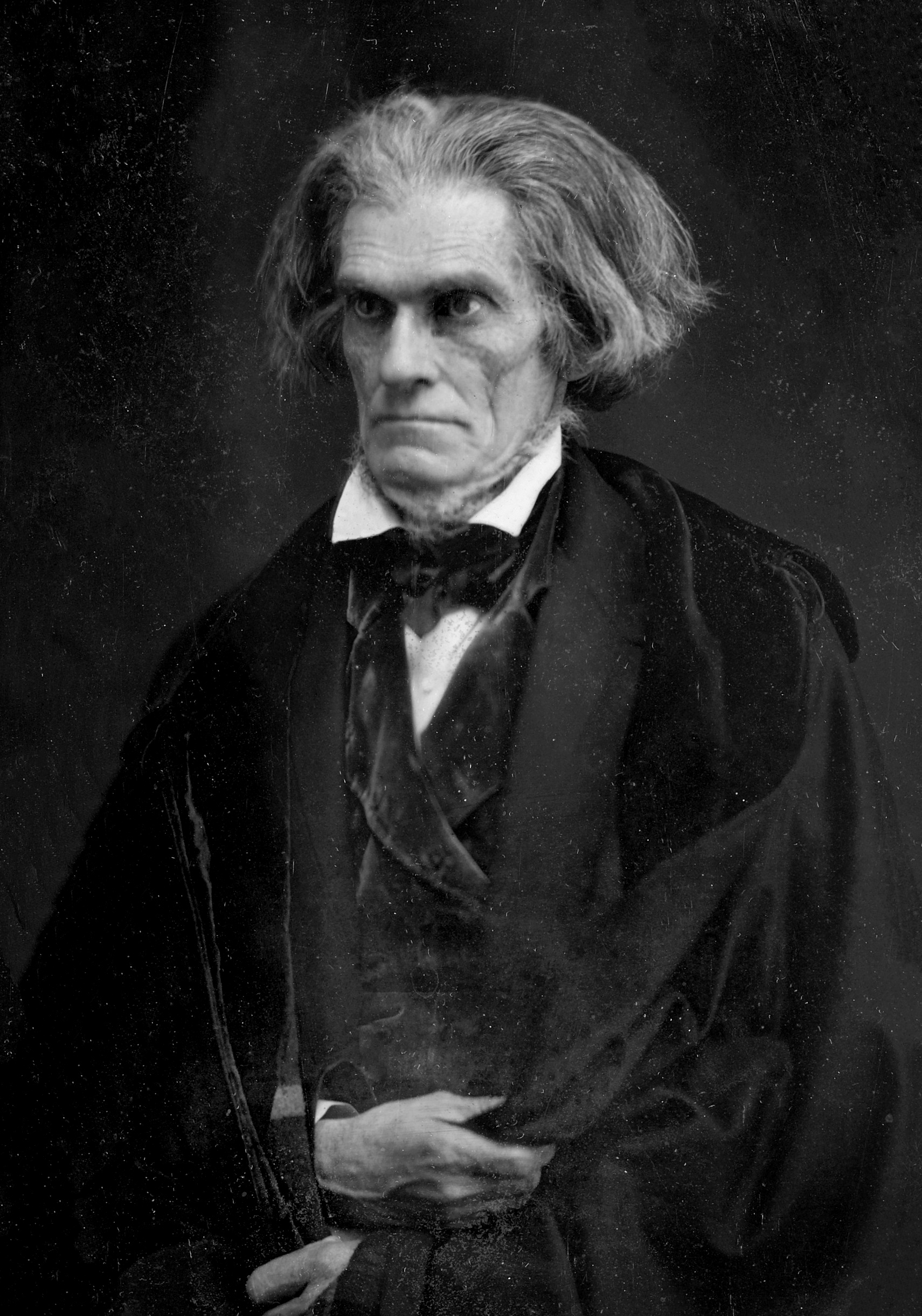

Source: John C. Calhoun, Congressional Globe, 31st Congress, 1st session (1850), 451-455. https://archive.org/details/americanhistoryt00ivunse/page/48/mode/2up