13 First Account of New England (1602)

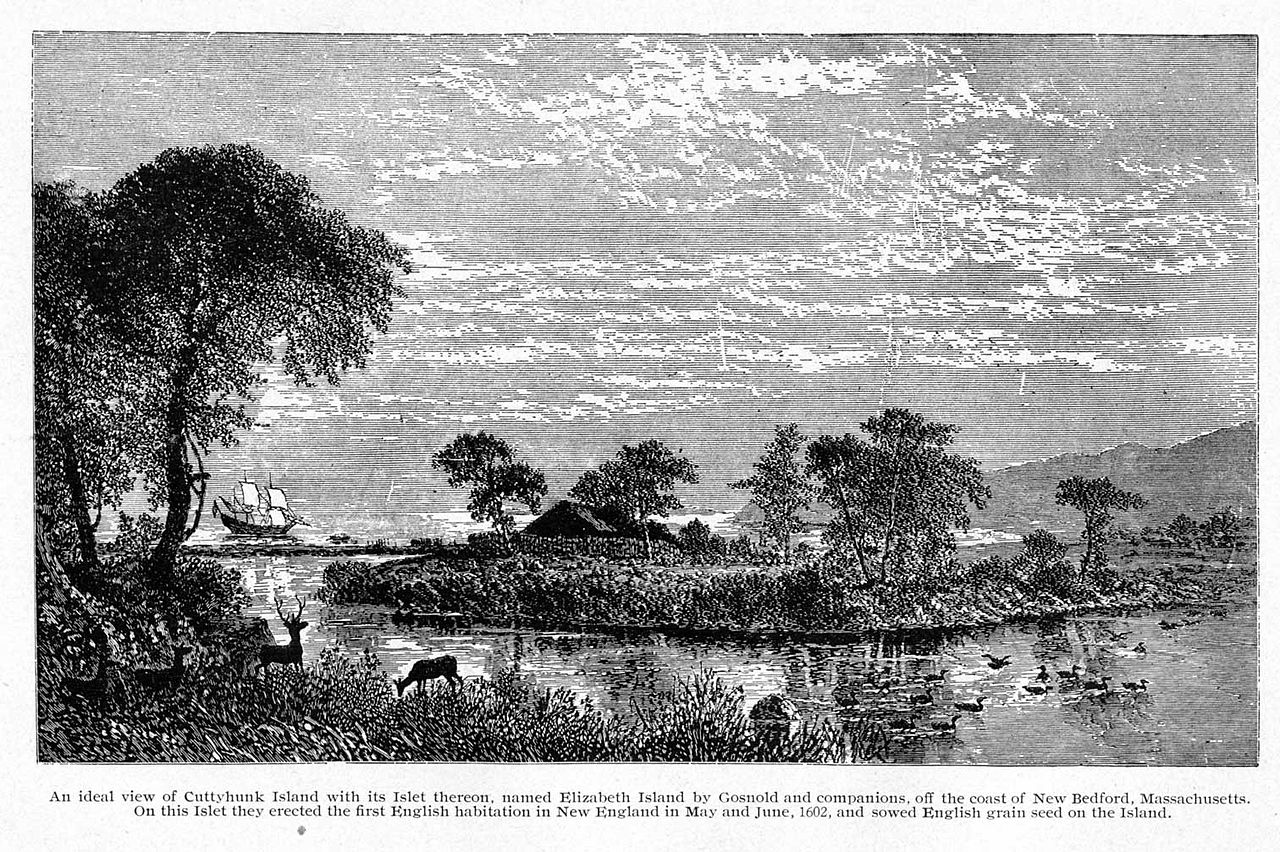

This is a description of an English expedition in 1602 to Cuttyhunk Island in what is now Buzzards Bay, just south of the Cape Cod peninsula near Martha’s Vineyard. The island, which is less than a mile and a half long, was a source of sassafras, which was valued in Europe.

Upon the six and twentieth of March 1602, being Friday, we went from Falmouth, being in all two & thirty persons, in a small bark of Dartmouth called the Concord, holding a course for the North part of Virginia . . . on Friday the fourteenth of May early in the morning we made the land, being full of fair trees, the land somewhat low, certain hummocks or hills lying into the land, the shore full of white sand, but very stony or rocky. And standing fair along by the shore about twelve of the clock the same day we came to an anchor where six Indians in a Basque-shallop [water-taxi] with mast and sail, an iron grapple, and a kettle of copper came boldly aboard us; one of them appareled with a waistcoat and breeches of black serge made after our sea fashion, hose and shoes on his feet. All the rest (saving one that had a pair of breeches of blue cloth) were all naked. These people are of tall stature, broad and grim visage, of a black swarthy complexion, their eyebrows painted white; their weapons are bows and arrows. It seemed by some words and signs they made, that some Basques or of St. John de Luz [a community in the French Pyrenees] have fished or traded in this place, being in the latitude of 43 degrees.

Captain Bartholomew Gosnold, myself, and three others went ashore, being a white sandy and very bold shore. And marching all that afternoon with our muskets on our necks, on the highest hills which we saw (the weather very hot) at length we perceived this headland to be parcel of the main [mainland] and sundry islands lying almost round about it. So returning (towards evening) to our shallop we espied an Indian, a young man of proper stature and of a pleasing countenance. And after some familiarity with him, we left him at the sea-side and returned to our ship. I am persuaded that in the months of March, April, and May, there is upon this coast better fishing and in as great plenty, as in Newfoundland. For the schools of Mackerel, herrings, Cod, and other fish that we daily saw as we went and came from the shore, were wonderful. And besides, the places where we took these Cods (and might in a few days have laden our ship) were but in seven fathoms of water and within less than a league of the shore; where in Newfoundland they fish in forty or fifty fathoms of water and far off.

The land somewhat low, full of goodly woods. At length we were come amongst many fair islands which we had partly discerned at our first landing, all lying within a league or two one of another and the outermost not above six or seven leagues from the main[land]. But coming to an anchor under one of them, we found it to be four English miles in compass [diameter], without house or inhabitant, saving a little old house made of boughs covered with bark, an old piece of a weir of the Indians to catch fish, and one or two places where they had made fires. This island, as also all the rest of these Islands, are full of all sorts of stones fit for building. Yet we found no towns nor many of their houses, although we saw many Indians which are tall big boned men, all naked saving they cover their privy parts with a black-hued skin, much like a Blacksmith’s apron, tied about their middle and between their legs behind. They gave us of their fish ready boiled (which they carried in a basket made of twigs, not unlike our osier [willow]) whereof we did eat and judged them to be fresh-water fish. They gave us also of their Tobacco, which they drink [smoke] green but dried into powder, very strong and pleasant and much better than any I have tasted in England. The necks of their pipes are made of clay hard dried (whereof in that island is great store both red and white) the other part is a piece of hollow copper, very finely closed and cemented together. We gave unto them certain trifles as knives, points, and such like, which they much esteemed.

From hence we went to another island, to the Northwest of this, and within a league or two of the main, full of high timbered Oaks, their leaves thrice so broad as ours; Cedars, straight and tall; Beech, Elm, Holly, Walnut trees in abundance, the fruit as big as ours. Hazelnut trees, Cherry trees, the leaf, bark and bigness not differing from ours in England, but the stalk bears the blossoms or fruit at the end thereof, like a cluster of Grapes, forty or fifty in a bunch. Sassafras trees great plenty all the island over, a tree of high price and profit. Also, in every island, and almost in every part of every island, are great store of Ground nuts, forty together on a string, some of them as big as hens’ eggs. They grow not two inches underground; the which nuts we found to be as good as Potatoes. Also, diverse sorts of shellfish, as Scallops, Muscles, Cockles, Lobsters, Crabs, Oysters, and Wilks, exceeding good and very great [large].

Hard by, we espied seven Indians and coming up to them, at first they expressed some fear. But being emboldened by our courteous usage and some trifles which we gave them, they followed us . . . the second day after our coming from the main we espied nine canoes or boats with fifty Indians in them, coming toward us. And being loth they should discover our fortification, we went out on the sea side to meet them. And coming somewhat near them, they all sat down upon the stones, calling aloud to us (as we rightly guessed) to do the like a little distance from them. Having sat a while in this order, Captain Gosnold willed me to go unto them, to see what countenance they would make. But as soon as I came up unto them, one of them to whom I had given a knife two days before in the main knew me (whom I also very well remembered) and smiling upon me, spoke somewhat unto their lord or captain which sat in the midst of them, who presently rose up and took a large Beaver skin from one that stood about him and gave it unto me. But I pointing towards Captain Gosnold, made signs unto him, that he was our captain. And after many signs of gratulations we became very great friends and gave them such meats as we had then ready dressed, whereof they misliked nothing but our mustard, whereat they made many a sour face. While we were thus merry, one of them had conveyed a target [shield] of ours into one of their canoes, which we suffered only to try whether they were in subjection to this L. [leader] to whom we made signs (by showing him another of the same likeness and pointing to the canoe) what one of his company had done. Who suddenly expressed some fear and speaking angrily to one about him (as we perceived by his countenance) caused it presently to be brought back again.

These people are exceeding courteous, gentle of disposition, and well conditioned, excelling all others that we have seen. I think they excel all the people of America; of stature much higher than we. Some of them are black thin bearded. They make beards of the hair of beasts and one of them offered a beard of their making to one of our sailors, for his that grew on his face, which because it was of a red color they judged to be none of his own. They are quick eyed and steadfast in their looks, fearless of others’ harms, as intending none themselves. Some of the meaner sort given to filching, which the very name of Savages (not weighing their ignorance in good or evil) may easily excuse. Their garments are of Deer skins. They pronounce our language with great facility; for one of them one day sitting by me, upon occasion I spoke smiling to him these words: “How now, sirrah, are you so saucy with my Tobacco?” Which words (without any further repetition) he suddenly spoke so plain and distinctly as if he had been a long scholar in the language. Their women (such as we saw) which were but three in all, were but low of stature, their eyebrows, hair, apparel, and manner of wearing like to the men. Fat and very well favored and much delighted in our company; the men are very dutiful towards them. And truly, the wholesomeness and temperature of this Climate does not only argue this people to be answerable to this description, but also of a perfect constitution of body, active, strong, healthful, and very witty, as the sundry toys of theirs cunningly wrought may easily witness.

Source: “Letter to Walter Raleigh” by John Brereton, in George Parker Winship, Sailors narratives of voyages along the New England coast, 1524-1624, 1905, 33-48. https://archive.org/details/sailorsnarrative00wins/page/n51/mode/2up