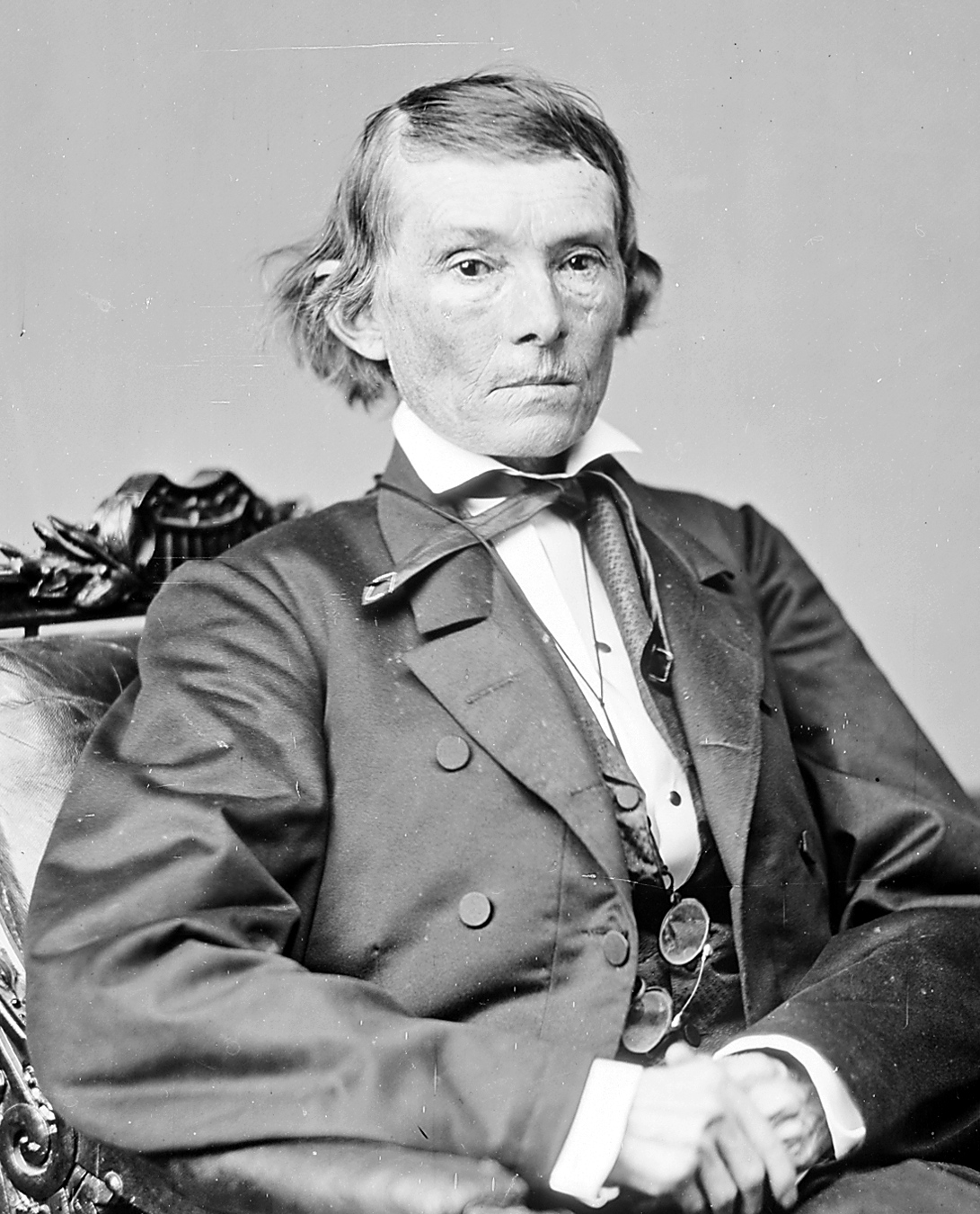

184 Southern “Opponent” of Secession (1860)

Fellow Citizens: I appear before you tonight at the request of Members of the Legislature and others, to speak of matters of the deepest interest that can possibly concern us all. My object is not to stir up strife but to allay it; not to appeal to your passions but to your reason. Let us therefore reason together. It is not my purpose to say aught to wound the feelings of any individual who may be present and if in the ardency with which I shall express my opinions I shall say anything which may be deemed too strong, let it be set down to the zeal with which I advocate my own convictions. There is with me no intention to irritate or offend.

The first question that presents itself is, shall the people of Georgia secede from the Union in consequence of the election of Mr. Lincoln to the Presidency of the United States? My countrymen, I tell you frankly, candidly, and earnestly that I do not think that they ought. In my judgment, the election of no man constitutionally chosen to that high office is sufficient cause to justify any State to separate from the Union. It ought to stand by and aid still in maintaining the Constitution of the country. To make a point of resistance to the Government, to withdraw from it because any man has been elected would put us in the wrong. We are pledged to maintain the Constitution. Many of us have sworn to support it. Can we therefore, for the mere election of any man to the Presidency and that too in accordance with the prescribed forms of the Constitution, make a point of resistance to the Government without becoming the breakers of that sacred instrument ourselves by withdrawing ourselves from it? Would we not be in the wrong? Whatever fate is to befall this country, let it never be laid to the charge of the people of the South and especially to the people of Georgia, that we were untrue to our national engagements. Let the fault and the wrong rest upon others. If all our hopes are to be blasted, if the Republic is to go down, let us be found to the last moment standing on the deck with the Constitution of the United States waving over our heads. Let the fanatics of the North break the Constitution if such is their fell purpose. Let the responsibility be upon them. I shall speak presently more of their acts. But let not the South, let us not be the ones to commit the aggression. We went into the election with this people. The result was different from what we wished. But the election has been constitutionally held. Were we to make a point of resistance to the Government and go out of the Union merely on that account, the record would be made up hereafter against us.

But it is said Mr. Lincoln’s policy and principles are against the Constitution and that if he carries them out, it will be destructive of our rights. Let us not anticipate a threatened evil. If he violates the Constitution, then will come our time to act. Do not let us break it because, forsooth, he may. If he does, that is the time for us to act. I think it would be injudicious and unwise to do this sooner. I do not anticipate that Mr. Lincoln will do anything to jeopardize our safety or security, whatever may be his spirit to do it. For he is bound by the Constitutional checks which are thrown around him, which at this time render him powerless to do any great mischief. This shows the wisdom of our system. The President of the United States is no Emperor, no Dictator — he is clothed with no absolute power. He can do nothing unless he is backed by power in Congress. The House of Representatives is largely in a majority against him. Is this the time then to apprehend that Mr. Lincoln, with this large majority in the House of Representatives against him, can carry out any of his unconstitutional principles in that body?

My countrymen, I am not of those who believe this Union has been a curse up to this time. There is nothing perfect in this world of human origin. But that this Government of our Fathers with all its defects comes nearer the objects of all good Governments than any other on the face of the earth, is my settled conviction. Have we not at the South as well as the North grown great, prosperous, and happy under its operation? Has any part of the world ever shown such rapid progress in the development of wealth and all the material resources of national power and greatness as the Southern States have under the General Government, notwithstanding all its defects?

I look upon this country with our Institutions as the Eden of the world, the Paradise of the Universe. It may be that out of it we may become greater and more prosperous, but I am candid and sincere in telling you that I fear if we yield to passion and without sufficient cause shall take that step, that instead of becoming greater or more peaceful, prosperous, and happy — instead of becoming Gods we will become demons and at no distant day commence cutting one another’s throats. This is my apprehension. Let us therefore, whatever we do, meet these difficulties, great as they are, like wise and sensible men and consider them in the light of all the consequences which may attend our action. Let us see first, clearly, where the path of duty leads and then we may not fear to tread therein.

Now then, my recommendation to you would be this: in view of all these questions of difficulty, let a Convention of the people of Georgia be called, to which they may be all referred. Let the Sovereignty of the people speak. I have no hesitancy in saying that the Legislature is not the proper body to sever our Federal relations, if that necessity should arise. Sovereignty is not in the Legislature. We the People are Sovereign! I am one of them and have a right to be heard. And so has every other citizen of the State. Our Constitutions, State and Federal, came from the people. They made both and they alone can rightfully unmake either.

Should Georgia determine to go out of the Union, I speak for one. Though my views might not agree with them, whatever the result may be, I shall bow to the will of her people. Their cause is my cause and their destiny is my destiny. And I trust this will be the ultimate course of all. The greatest curse that can befall a free people is civil war.

Before making reprisals, we should exhaust every means of bringing about a peaceful settlement of the controversy. At least let these offending and derelict States know what your grievances are. And if they refuse as I said to give us our rights under the Constitution, I should be willing as a last resort to sever the ties of our Union with them.

My own opinion is that if this course be pursued and they are informed of the consequences of refusal, these States will recede, will repeal their nullifying acts. But if they should not, then let the consequences be with them and the responsibility of the consequences rest upon them.

I am, as you clearly perceive, for maintaining the Union as it is if possible. I will exhaust every means, thus, to maintain it with an equality in it. My position then, in conclusion, is for the maintenance of the honor, the rights, the equality, the security, and the glory of my native State in the Union, if possible. But if these cannot be maintained in the Union, then I am for their maintenance, at all hazards, out of it. Next to the honor and glory of Georgia, the land of my birth, I hold the honor and glory of our common country.

Source: Alexander H. Stephens, A Constitutional View of the late War between the States (1870), II, 279-299. https://archive.org/details/americanhistoryt00ivunse/page/164/mode/2up