111 Yellow Fever in Philadelphia (1793)

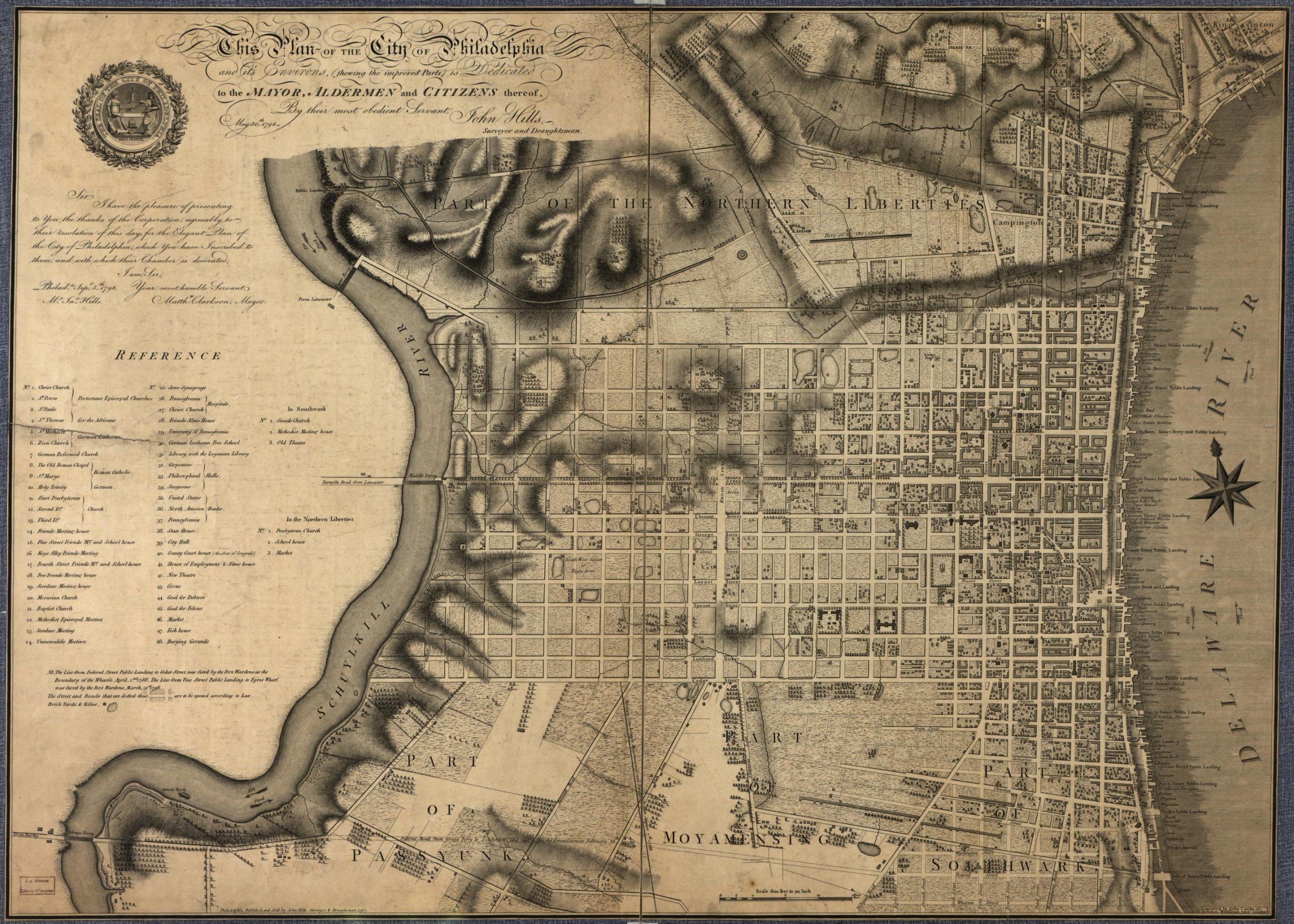

I had scarcely become settled in Philadelphia when in July 1793 the yellow fever broke out and, spreading rapidly in August, obliged all the citizens who could remove to seek safety in the country. My father took his family to Bristol on the Delaware and in the last of August I followed him. Having engaged in commerce and having a ship at the wharf loading for Liverpool, I was compelled to return to the city on the 8th of September and spend the 9th there. My business took me down to the Swedes’ Church and up Front Street to Walnut Street wharf where I had my counting-house. Everything looked gloomy and forty-five deaths were reported for the 9th. In the afternoon when I was about returning to the country, I passed by the lodgings of the Vicomte de Noailles, who had fled from the Revolutionists of France. He was standing at the door and calling to me, asked me what I was doing in town. “Fly,” said he, “as soon as you can, for pestilence is all around us.” And yet it was nothing then to what it became three or four weeks later, when from the first to the twelfth of October one thousand persons died. On the twelfth a smart frost came and checked its ravages.

The horrors of this memorable affliction were extensive and heart-rending. Nor were they softened by professional skill. The disorder was in a great measure a stranger to our climate and was awkwardly treated. Its rapid march, being from ten victims a day in August to one hundred a day in October, terrified the physicians and led them into contradictory modes of treatment. They as well as the guardians of the city were taken by surprise. No hospitals or hospital stores were in readiness to alleviate the sufferings of the poor. For a long time nothing could be done other than to furnish coffins for the dead and men to bury them. At length a large house in the neighborhood was appropriately fitted up for the reception of patients and a few pre-eminent philanthropists volunteered to superintend it. At the head of them was Stephen Girard, who has since become the richest man in America.

In private families the parents, the children, the domestics lingered and died, frequently without assistance. The wealthy soon fled. The fearless or indifferent remained from choice, the poor from necessity. The inhabitants were reduced thus to one-half their number, yet the malignant action of the disease increased so that those who were in health one day were buried the next. The burning fever occasioned paroxysms of rage which drove the patient naked from his bed to the street and in some instances to the river where he was drowned. Insanity was often the last stage of its horrors.

In November, when I returned to the city and found it repeopled, the common topic of conversation could be no other than this unhappy occurrence. The public journals were engrossed by it and related many examples of calamitous suffering. One of these took place on the property adjacent to my father’s. The respectable owner, counting upon the comparative security of his remote residence from the heart of the town, ventured to brave the disorder and fortunately escaped its attack. He told me that in the height of the sickness, when death was sweeping away its hundreds a week, a man applied to him for leave to sleep one night on the stable floor. The gentleman like everyone else inspired with fear and caution, hesitated. The stranger pressed his request, assuring him that he had avoided the infected parts of the city, that his health was very good, and promised to go away at sunrise the next day. Under these circumstances he admitted him into his stable for that night. At peep of day the gentleman went to see if the man was gone. On opening the door he found him lying on the floor delirious and in a burning fever. Fearful of alarming his family, he kept it a secret from them and went to the committee of health to ask to have the man removed.

That committee was in session day and night at the City Hall in Chestnut Street. The spectacle around was new, for he had not ventured for some weeks so low down in town. The attendants on the dead stood on the pavement in considerable numbers soliciting jobs and until employed they were occupied in feeding their horses out of the coffins which they had provided in anticipation of the daily wants. These speculators were useful and albeit with little show of feeling, contributed greatly to lessen by competition the charges of interment. The gentleman passed on through these callous spectators until he reached the room in which the committee was assembled and from whom he obtained the services of a quack doctor, none other being in attendance. They went together to the stable where the doctor examined the man and then told the gentleman that at ten o’clock he would send the cart with a suitable coffin into which he requested to have the dying stranger placed. The poor man was then alive and begging for a drink of water. His fit of delirium had subsided, his reason had returned, yet the experience of the soi-disant [presumed] doctor enabled him to foretell that his death would take place in a few hours. It did so and in time for his corpse to be conveyed away by the cart at the hour appointed. This sudden exit was of common occurrence. The whole number of deaths in 1793 by yellow fever was more than four thousand. Again it took place in 1797, ’98 and ’99 when the loss was six thousand, making a total in these four years of ten thousand.

Source: Samuel Breck, Recollections (edited by H. E. Scudder, 1877), 193-196. https://archive.org/details/toldcontemporari03hartrich/page/38/mode/2up