9. Jefferson’s New Revolution

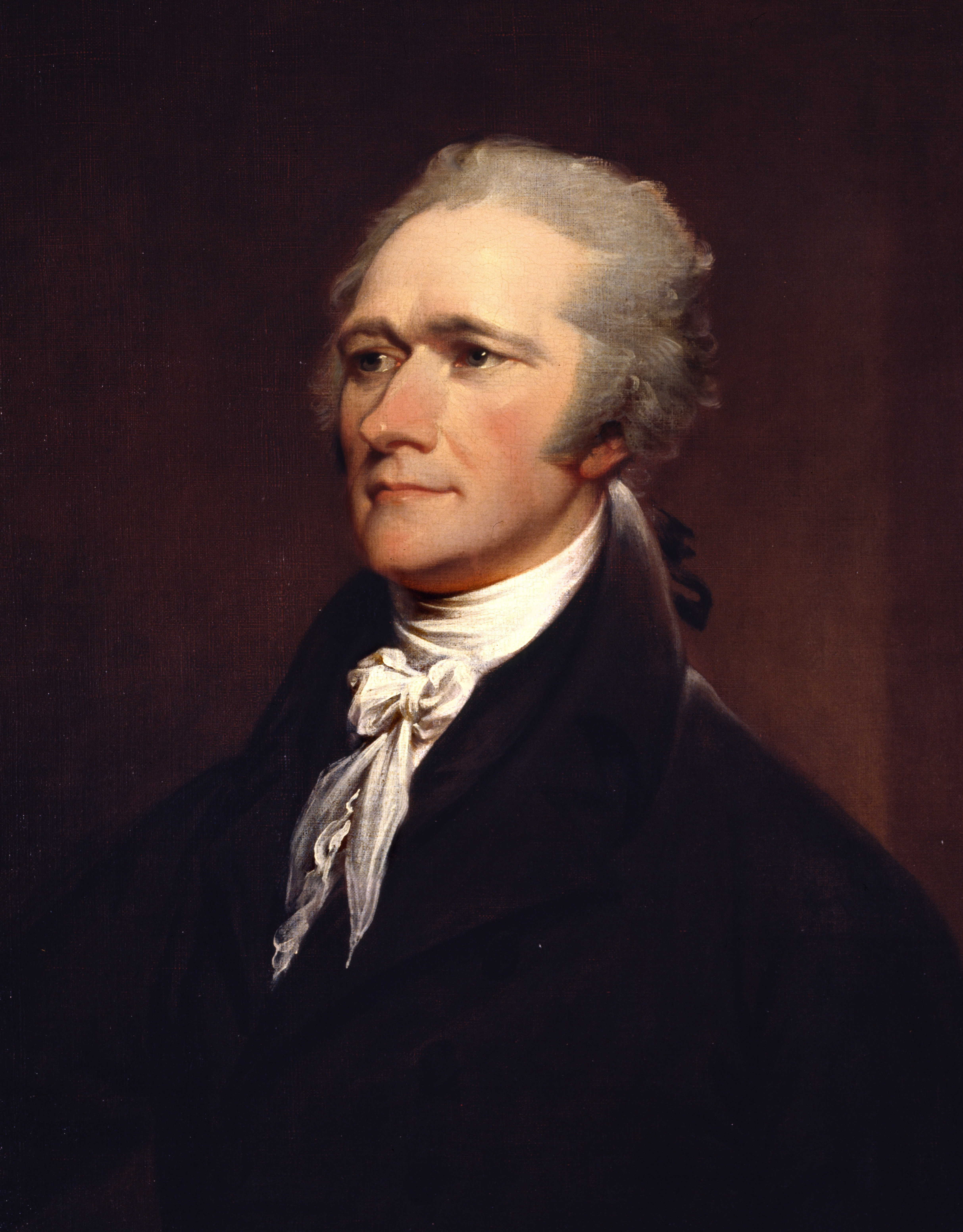

Alexander Hamilton, Washington’s secretary of the treasury, was an ardent nationalist who believed a strong federal government could solve many of the new country’s financial ills. In 1789 the United States federal debt was over $53 million. The states had a combined debt of around $25 million, and the nation had been unable to pay its debts in the 1780s and was considered a credit risk by European countries. Hamilton wrote three reports offering solutions to the economic crisis brought on by these problems. The first addressed public credit, the second addressed banking, and the third addressed raising revenue. Hamilton’s Report on Public Credit recommended that the new federal government honor all its debts, including all paper money issued by the Confederation and the states during the war, at face value. Hamilton wanted wealthy American creditors who held large amounts of paper money to be invested, literally, in the new national government. Hamilton proposed that the federal government sell bonds to the public that would yield interest payments. Creditors could exchange their old notes for the new government bonds. Hamilton wanted to satisfy creditors, citing the goal of “doing justice to the creditors of the nation.” But the majority of both Confederation and state notes had found their way into the hands of speculators who had bought them from hard-pressed veterans in the 1780s at a fraction of their face value. Because these speculators held so many notes, many in Congress objected that Hamilton’s plan would benefit them at the expense of the original note-holders. One of those who opposed Hamilton’s 1790 report was James Madison, who questioned the fairness of a plan that seemed to cheat poor soldiers.

States with a large debt like South Carolina supported Hamilton’s plan, while states with less debt like North Carolina did not. Hamilton worked out a compromise with Virginians Madison and Jefferson, where in return for their support he would give up New York City as the nation’s capital and agree on a more southern location, which they preferred. In July 1790, a site along the Potomac River was selected as the new “federal city,” which became the District of Columbia. Hamilton’s plan to convert notes to bonds worked extremely well to restore European confidence in the U.S. economy. It also proved a windfall for creditors and for speculators who had bought up state and Confederation notes at far less than face value. But it immediately generated controversy about the size and scope of the government. Some saw the plan as an unjust use of federal power, and their objections increased when Hamilton proposed a Bank of the United States modeled on the Bank of England. The bank would issue loans to American merchants and federal bank notes while serving as a repository of government revenue from the sale of land. Jefferson, in particular, argued that the Constitution did not permit the creation of a national bank. In response, Hamilton invoked the Constitution’s implied powers. President Washington backed Hamilton’s position and signed legislation creating the bank in 1791. Finally, using the power to tax as provided under the Constitution, Hamilton decided to tax American-made whiskey and in 1791 Congress authorized a tax of 7.5 cents per gallon of whiskey and rum. Although many citizens paid what they considered a “sin tax” on an unneeded luxury, trouble erupted in four western Pennsylvania counties in an uprising known as the Whiskey Rebellion.

Farmers in the western counties of Pennsylvania produced whiskey from their grain for economic reasons. Without adequate roads to transport a bulky grain harvest, frontier farmers distilled their grains into less bulky spirits that were more cost-effective to transport and had a higher value at a lower mass. Since these farmers depended on the sale of whiskey for the cash they used to buy goods they couldn’t produce on their farms (as well as pay their taxes), many citizens in western Pennsylvania viewed the new tax as further proof that the new Federalist government favored the commercial classes on the coast at the expense of farmers in the West. Supporters of the tax argued that it helped stabilize the economy and that its cost could easily be passed on to consumers by raising prices, and would not be paid by the farmer-distiller. But the tax collectors were still trying to take money out of the farmers’ pockets and there was no guarantee they would be able to sell the whiskey at higher prices. In 1794 angry citizens rebelled against the federal officials enforcing the federal law. Like the Sons of Liberty before the American Revolution and the Massachusetts regulators of Shays’s Rebellion, the whiskey rebels used violence to protest policies they saw as unfair. They tarred and feathered federal officials, intercepted the federal mail, and intimidated wealthy citizens. The extent of their discontent was represented most extremely by talk of forming an independent western commonwealth, and they even began negotiations with British and Spanish representatives, hoping to secure their support for independence from the United States. The rebels also contacted their backcountry neighbors in Kentucky and South Carolina, circulating the idea of secession. George Washington led a force of 13,000 men; the only time a US President has ever led an army in the field and the only time a Commander in Chief has ever taken the field against US citizens.

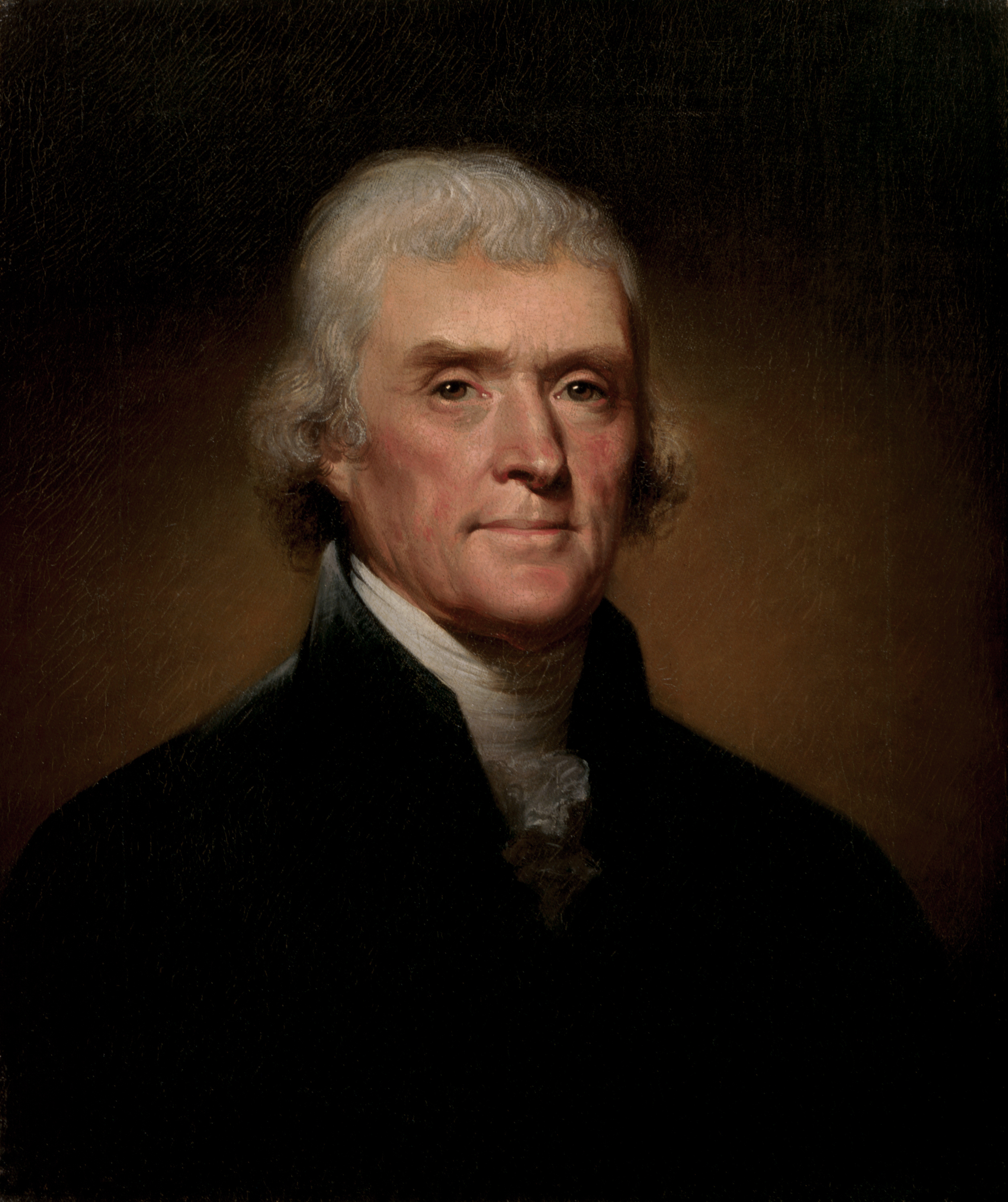

Thomas Jefferson, who had returned to the United States in 1790 after serving as a diplomat in France, tried unsuccessfully to convince Washington to block the creation of a national bank. He also took issue with the favoritism given to commercial classes in American cities. Jefferson thought urban life widened the gap between the wealthy few and landless poor workers who, because of their oppressed condition, could never be good republican citizens. Rural life, Jefferson thought, offered more opportunities for property ownership and virtue. Jefferson believed that self-sufficient, property-owning republican citizens or yeoman farmers held the key to the success and longevity of the American republic. To him, Hamilton’s program seemed to encourage economic inequalities and work against the ordinary American yeoman. Jefferson turned to his friend Philip Freneau to help organize the effort through the publication of the National Gazette as a counter to the Federalist press, especially the Gazette of the United States. From 1791 until 1793, when it ceased publication, Freneau’s partisan paper attacked Hamilton’s program and Washington’s administration. “Rules for Changing a Republic into a Monarchy,” written by Freneau, is an example of the type of attack aimed at the elitism of the Federalist Party. Newspapers in the 1790s became enormously important in American culture as partisans like Freneau attempted to sway public opinion. These newspapers did not aim to be objective; they served to broadcast the views of a particular party.

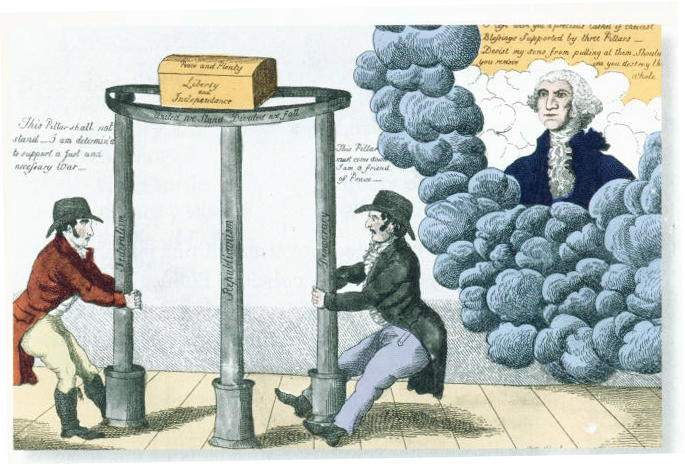

Opposition to the Federalists led to the formation of Democratic-Republican societies that championed limited government. To Democratic-Republicans, the Federalists promoted aristocracy and a monarchical government—a betrayal of what many believed to be the goal of the American Revolution. While wealthy merchants and planters formed the core of the Federalist leadership, members of the societies in cities like Philadelphia and New York came from the ranks of artisans. These citizens saw themselves as acting in the spirit of 1776. Their political efforts against the Federalists were a battle to preserve republicanism, to promote the public good against private self-interest. In their strident newspaper attacks, they also worked to undermine traditional forms of deference and subordination to aristocrats, in this case the Federalist elites. Some members of northern Democratic-Republican clubs denounced slavery as well.

The French Revolution, which began in 1789, further split American thinkers into different ideological camps and deepened the political divide between Federalists and their Democratic-Republican foes. At first, in 1789 and 1790, the revolution in France appeared to be a new chapter in the rejection of corrupt monarchy, a trend inspired by the American Revolution. A constitutional monarchy replaced the absolute monarchy of Louis XVI in 1791, and in 1792, France was declared a republic. Republican liberty, the creed of the United States, seemed to be ushering in a new era in France. Thomas Paine, who was living in London when the Revolution began, wrote a defense of the French in The Rights of Man, which once again attacked monarchy and supported progressive taxes and social programs to alleviate the poverty of the masses. The new French Republic made Paine an honorary citizen and invited him to join the new National Convention as well as the nine-member Constitutional Committee tasked with writing a new basis for the republican government.

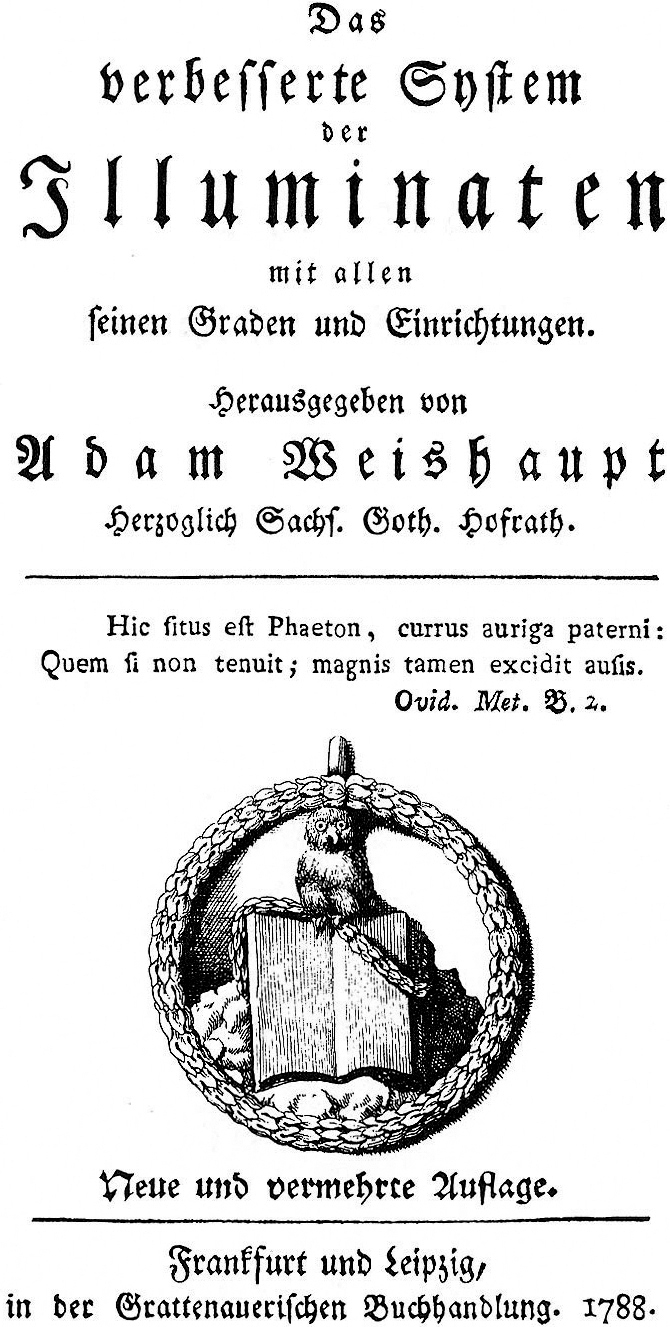

1793 and 1794 challenged the simple interpretation of the French Revolution as a happy chapter in the unfolding triumph of republican government over monarchy. The French king and queen were executed in January 1793, beginning the Reign of Terror, a period of extreme violence against perceived enemies of the revolutionary government. Jacobin revolutionaries following Maximillian Robespierre advocated direct representative democracy, dismantled Catholicism, renamed the months of the year, and relentlessly employed the guillotine against their enemies. When Thomas Paine protested the execution of Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette, the Jacobins declared him an enemy of the state and sentenced him to death. Paine spent seven months in prison awaiting his sentence and was freed in late July 1794 when Robespierre was overthrown and went to the guillotine himself. Federalists viewed these excesses with growing alarm, fearing that the radicalism of the French Revolution might infect the minds of citizens at home. Many Federalists believed that an international conspiracy called the Illuminati was trying to overthrow the US government and establish an American reign of terror. Democratic-Republicans interpreted the same events with greater optimism, seeing them as a necessary evil of eliminating the monarchy and aristocratic culture that supported the privileges of a hereditary class of rulers. The controversy in the United States intensified when France declared war on Great Britain and Holland in February 1793. The French requested a large repayment of the money the Continental Congress had borrowed from France during the Revolutionary War. Americans worried Great Britain would judge any aid given to France as a hostile act. Washington declared the United States neutral in 1793, but Democratic-Republican groups denounced neutrality and declared their support of the French republicans. The Federalists used the violence of the French revolutionaries as a reason to attack Democratic-Republicanism in the United States, arguing that Jefferson and Madison would lead the country down a similarly disastrous path toward mob rule and anarchy.

Unlike the American Revolution, which ultimately strengthened the institution of slavery and the powers of American slaveholders, the French Revolution inspired slave rebellions in the Caribbean including a 1791 slave uprising in the French colony of Saint-Domingue, the western portion of the island of Hispaniola which the French had occupied since the end of the seventeenth century. Thousands of slaves overthrew the brutal system of sugar plantation slavery and took control of a large section of the island, burning plantations and killing the white planters who had worked tens of thousands of enslaved Africans to death. When Jacobins led by Robespierre abolished slavery in the French empire, and both Spain and England attacked Saint-Domingue, hoping to add the colony to their own empires and reinstitute slave-based sugar production. Toussaint L’Ouverture, a former slave, led a five-year fight against Spain and England to free Haiti of slavery and further European colonialism. Because revolutionary France had abolished slavery, Toussaint aligned himself with France, hoping to keep Spain and England at bay.

Westward expansion and war between Great Britain and France in the 1790s shaped early United States foreign policy. As a new, indebted, and relatively weak nation, the American republic had no control over European events and no real leverage to obtain its goals of trading freely in the Atlantic. George Washington, reelected in 1792 by an overwhelming majority, refused to run for a third term, eliminating the threat that his presidency would become a monarchy and setting a precedent for future presidents. In the presidential election of 1796, the Federalist and Democratic-Republican parties competed for the first time. Partisan division over the French Revolution and the Whiskey Rebellion fueled the divisiveness and Washington’s vice president, Federalist John Adams, defeated his Democratic-Republican rival Thomas Jefferson by a narrow margin of only three electoral votes. Adams won the New England and Mid-Atlantic states and Jefferson took the South and Pennsylvania. As loser in the presidential race, Jefferson became Adams’s Vice President (“Tickets” including both the presidential and vice-presidential candidate began in 1800 and a separate ballot for Vice President was implemented in 1804).

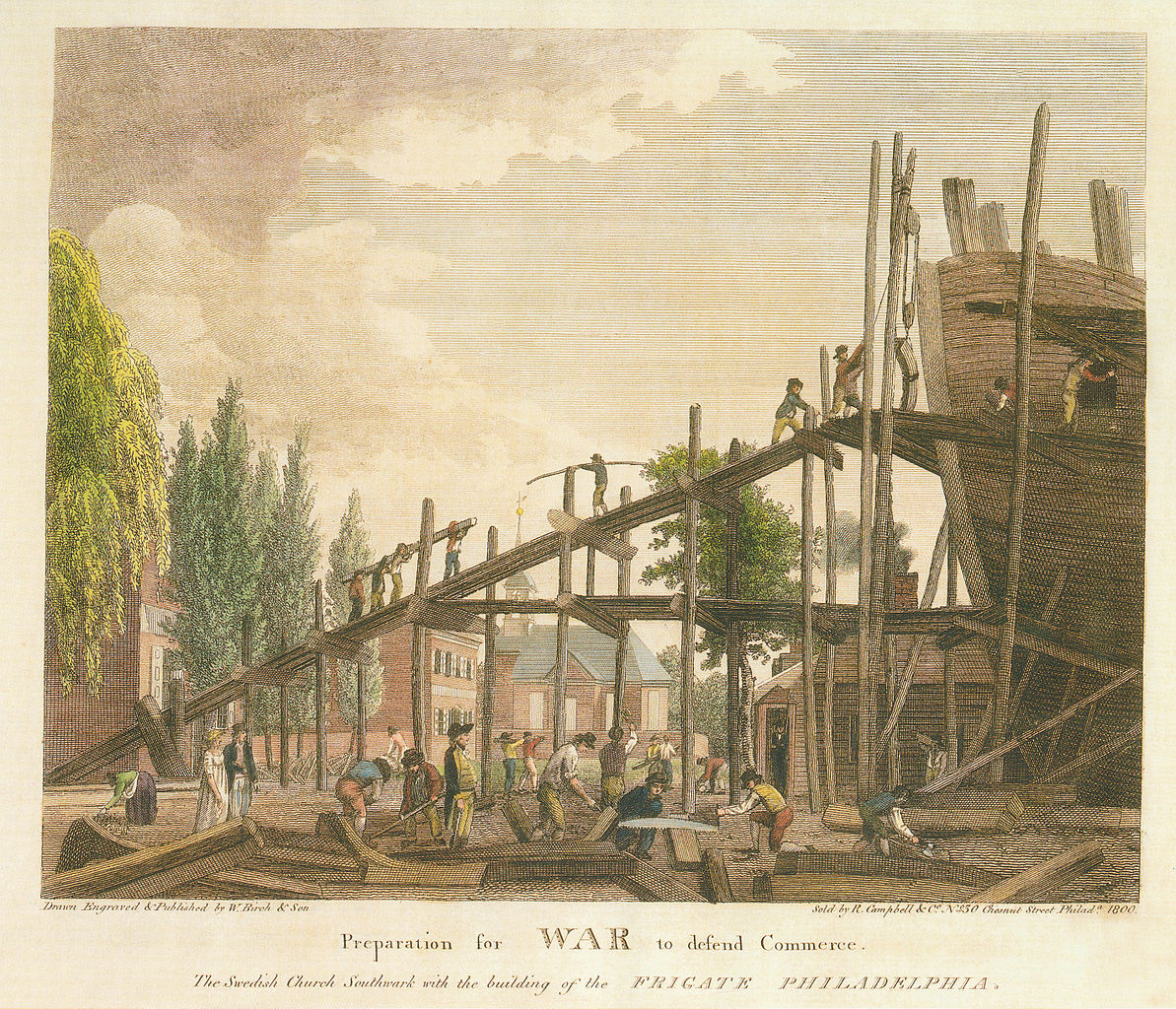

To Federalist president John Adams, relations with France posed the biggest problem. After the execution of Robespierre and the end of the Reign of Terror, the French wrote a new constitution that backed away from the democratic ideals of the revolution and a five-man committee called the Directory ruled France from 1795 to 1799. The Directory was continually at war with coalitions of enemies including the Ottoman Empire, Austria, Prussia, and the Kingdom of Naples. Great Britain was a constant foe and France issued decrees stating that any ship carrying British goods could be seized on the high seas. In practice, this meant the French would target American ships, especially those in the West Indies, where the United States conducted a brisk trade with the British. France declared its 1778 treaty with the United States null and void, and France and the United States waged an undeclared war from 1796 to 1800. Between 1797 and 1799, the French seized 834 American ships, and President Adams urged the buildup of the U.S. Navy, which had consisted of only a single vessel at the time of his election in 1796.

In 1797, President Adams sought a diplomatic solution to the conflict with France and dispatched envoys to negotiate terms. The French foreign minister, Charles-Maurice de Talleyrand, told the American envoys that the United States must repay all outstanding debts owed to France, lend France 32 million guilders (Dutch currency), and pay a £50,000 bribe before any negotiations could take place. News of the attempt to extract a bribe, known as the XYZ affair, outraged the American public and turned public opinion against France. In the court of public opinion, Federalists appeared to have been correct in their interpretation of France, while the pro-French Democratic-Republicans had been misled. At about the same time, rumors began to circulate of a German secret society called the Illuminati that critics accused of starting the French Revolution and attempting to spread the anarchist-democratic ideals of that revolution to America. Federalist politicians and American pastors (including Jedediah Morse, a very influential minister and author and father of the painter of the Adams portrait above) wrote and preached to warn Americans against the threat of the secret (and Catholic) Illuminati who they imagined had infiltrated and taken over the rival Democratic-Republican party. No evidence was ever found to support their accusations, and the conspiracy theories diminished after the election of Jefferson failed to result in the destruction of the republic.

The complicated situation in Haiti, which remained a French colony in the late 1790s under the control of the former slaves who had rebelled against the white planters, also came to the attention of President Adams. The Haitian leader Toussaint L’Ouverture, who had to contend with various domestic rivals seeking to displace him as well as a five-year long British invasion, wished to end the U.S. embargo on France and its colonies. In early 1799, in order to capitalize upon trade in the lucrative West Indies and undermine France’s hold on the island, Congress ended the ban on trade with Haiti—a move that acknowledged L’Ouverture’s leadership, to the horror of American slaveholders.

The complicated situation in Haiti, which remained a French colony in the late 1790s under the control of the former slaves who had rebelled against the white planters, also came to the attention of President Adams. The Haitian leader Toussaint L’Ouverture, who had to contend with various domestic rivals seeking to displace him as well as a five-year long British invasion, wished to end the U.S. embargo on France and its colonies. In early 1799, in order to capitalize upon trade in the lucrative West Indies and undermine France’s hold on the island, Congress ended the ban on trade with Haiti—a move that acknowledged L’Ouverture’s leadership, to the horror of American slaveholders.

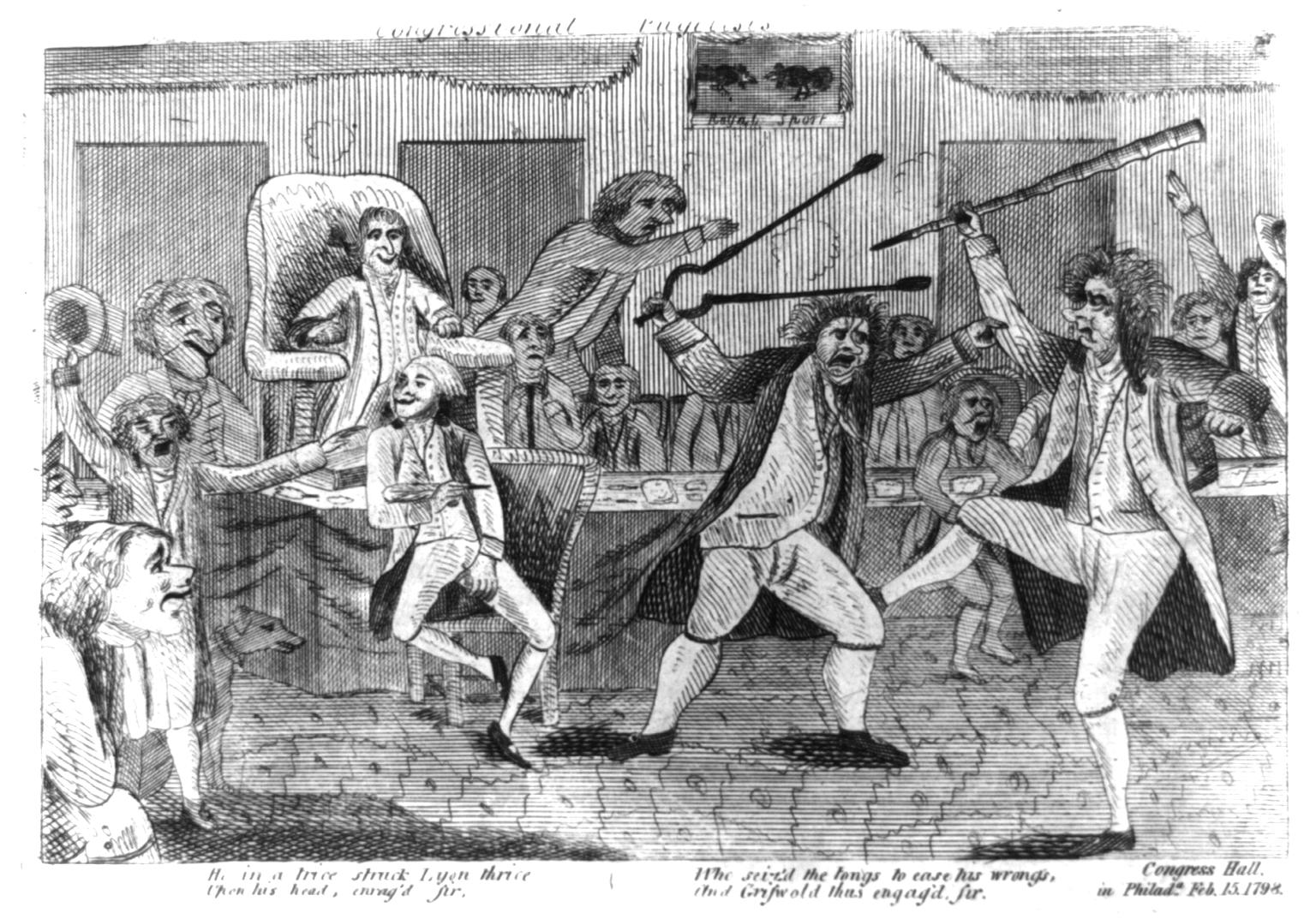

The surge of animosity against France during the undeclared war led Congress to pass several measures that in time undermined Federalist power. These 1798 war measures, known as the Alien and Sedition Acts, aimed to increase national security against what most had come to regard as the French menace and the Illuminati. The Alien Act and the Alien Enemies Act took particular aim at French immigrants fleeing the West Indies by giving the president the power to deport new arrivals who appeared to be a threat to national security. The act expired in 1800 with no immigrants having been deported. The Sedition Act was directed against U.S. citizens, imposing up to five years’ imprisonment and a massive fine of $5,000 on people convicted of speaking or writing “in a scandalous or malicious” manner against the government of the United States. Twenty-five men, all members of the opposition party, were indicted under the act, and ten were convicted. One of these was Congressman Matthew Lyon, Democratic-Republican representative from Vermont, who had launched his own newspaper, The Scourge Of Aristocracy and Repository of Important Political Truth.

The Alien and Sedition Acts raised important constitutional questions about the freedom of the press provided under the First Amendment. Democratic-Republicans argued that the acts were evidence of the Federalists’ intent to squash individual liberties and, by enlarging the powers of the national government, crush states’ rights. Jefferson and Madison mobilized the response to the Adams administration’s laws in statements known as the Virginia and Kentucky Resolutions, which argued that the acts were illegal and unconstitutional. The resolutions introduced the idea of nullification, the right of states to nullify acts of Congress, and advanced the argument of states’ rights. The ideas introduced in these resolutions would later become central in the fight over slavery. The undeclared war with France came to an end in 1800, when President Adams was able to secure the Treaty of Mortefontaine. His willingness to open talks with France divided the Federalist Party, but the treaty reopened trade between the two countries and ended the French practice of taking American ships on the high seas.

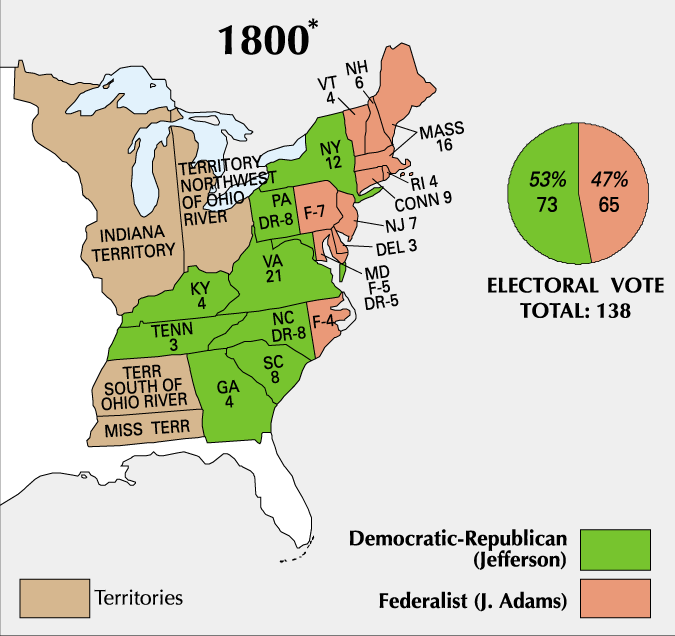

In 1800, another close election swung the other way. Jefferson picked up half of Maryland’s electoral votes but lost nearly half of Pennsylvania’s. The big difference was that by making New York Senator Aaron Burr his running-mate, Jefferson won all of New York’s 12 electoral votes, beginning a long period of Democratic-Republican government. The term “Revolution of 1800″ refers to the first transfer of power from one party to another in American history, when the presidency passed from Federalist John Adams to his vice president and political adversary, Democratic-Republican Thomas Jefferson. The peaceful transition of political power from one political party to another without bloodshed set an important precedent, especially after the rhetoric of the campaign which included suggestions that Jefferson’s party was a puppet for foreign powers or the Illuminati, and that anarchy and chaos would follow a Federalist defeat.

The election was much more divisive than the 1796 election had been, as both the Federalist and Democratic-Republican Parties waged a mudslinging campaign unlike any seen before. Because the Federalists were badly divided, the Democratic-Republicans gained political ground. Alexander Hamilton, who disagreed with President Adams’s approach to France, wrote a lengthy letter, meant for people within his party, attacking his fellow Federalist Adams’ character and judgment and ridiculing his handling of foreign affairs. Democratic-Republicans happily reprinted the letter. Jefferson viewed participatory democracy as a positive force for the republic, a direct departure from Federalist views. His version of participatory democracy was only slightly more inclusive than that of the Federalists, however, extending only to the white yeoman farmers in whom Jefferson placed great trust. While Federalist statesmen, like the architects of the 1787 Constitution, feared a pure democracy and preferred to vest political power in the hands of merchants, bankers, and wealthy plantation owners, Jefferson was far more optimistic that the common American farmer could be trusted to make good decisions. Jefferson had cheered the French Revolution and had not objected when the French republic instituted the Terror to ensure the monarchy would not return. While residing in France in the late 1780s, Jefferson had written to a U.S. diplomat that “The tree of liberty must be refreshed from time to time with the blood of patriots and tyrants. It is its natural manure.” By 1799, however, he had rejected the cause of France because of his opposition to Napoleon’s seizure of power and creation of a dictatorship.

Over the course of two terms as president, Jefferson reversed the policies of the Federalist Party by turning away from urban commercial development and early industrialization. Instead, he promoted agriculture through the sale of western public lands in small and affordable lots. Perhaps Jefferson’s most lasting legacy is his vision of an “empire of liberty.” He distrusted cities and instead hoped to build a rural republic of land-owning white men, or yeoman republican farmers. He wanted the United States to be the breadbasket of the world, exporting its agricultural commodities without suffering the ills of urbanization and industrialization. Men who worked for wages, he believed, could be intimidated by their employers into voting for the candidates preferred by their bosses (Ballots were not secret during this period; Massachusetts was the first state to adopt a secret ballot in 1888). Since American yeomen would own their own land, they could stand up against those who might try to influence their votes with threats or promises. Jefferson championed the rights of states and insisted on limited federal government as well as limited taxes. This stood in stark contrast to the Federalists’ insistence on a strong, active federal government. Jefferson also believed in fiscal austerity. He pushed for, and Congress approved, an end of all internal taxes such as those on whiskey and rum. The most significant trimming of the federal budget came at the expense of the military; Jefferson did not believe in maintaining a costly military during peacetime and he slashed the size of the navy Adams had worked to build. Nonetheless, Jefferson responded to the capture of American ships and sailors by pirates off the coast of North Africa by sending the U. S. Navy to war against the Muslim Barbary States in 1801, the first conflict fought by Americans overseas.

The slow decline of the Federalists, which began under Jefferson, led to a period of one-party rule in national politics. Historians call the years between 1815 and 1828 the “Era of Good Feelings” and highlight the “Virginia dynasty” of the time, since the next two presidents who followed Jefferson, James Madison and James Monroe, both hailed from his home state. Like Jefferson, they both owned slaves and represented the Democratic-Republican Party. Though Federalists continued to enjoy regional popularity, especially in the Northeast, their days of prominence in setting foreign and domestic policy had ended. And partisan divisions sometimes flared up into violence. The animosity between the political parties exploded in 1804, when Aaron Burr, Jefferson’s vice president, killed Federalist Alexander Hamilton in a duel. When Democratic-Republican Burr discovered he would not be Jefferson’s running-mate in 1804, he ran for governor of New York. Burr lost to another Democratic-Republican, but blamed his defeat on Hamilton, who had been quoted in a newspaper article written to discredit him. On July 11, the two rivals met in New Jersey for a duel in which Burr shot Hamilton.

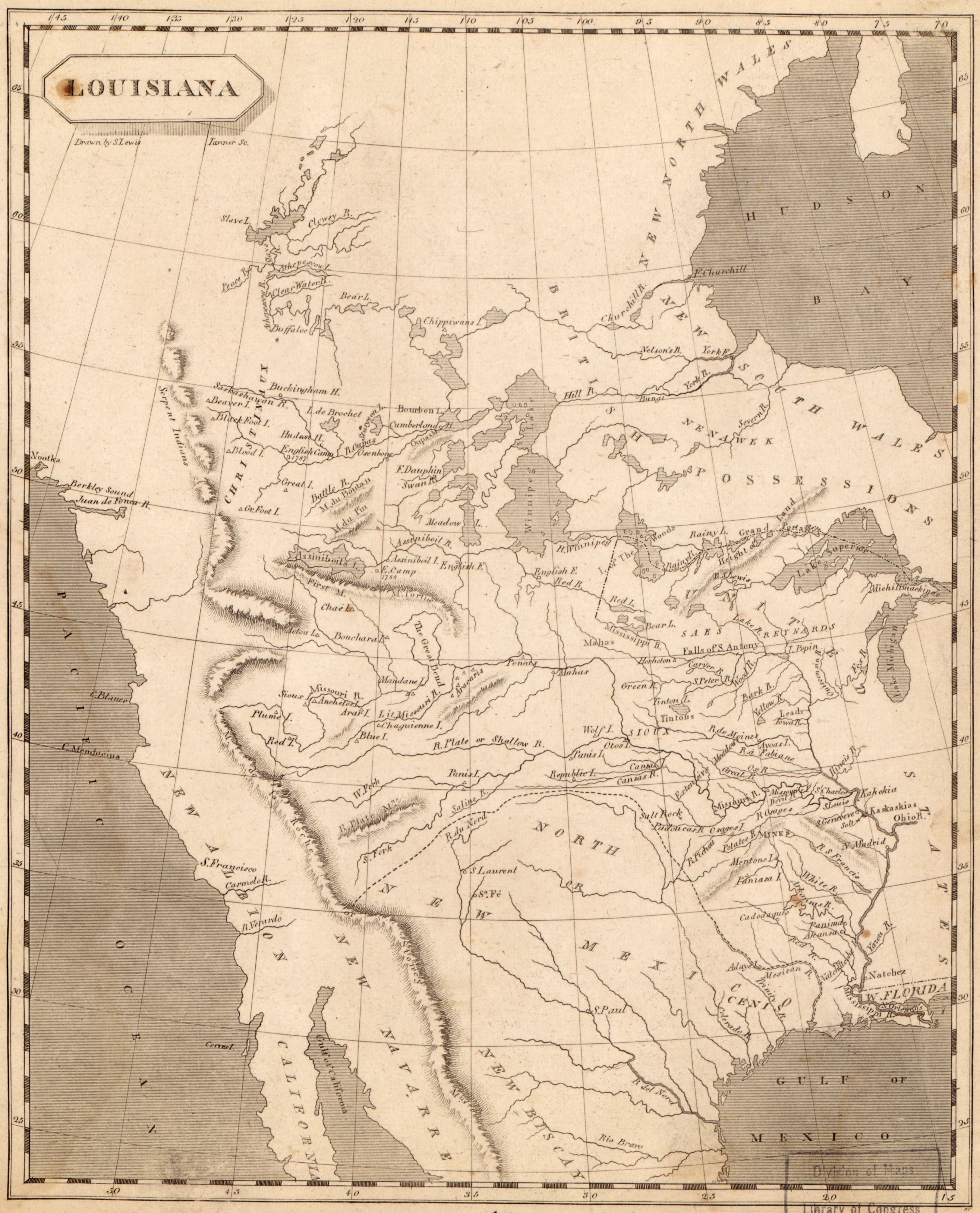

Jefferson realized his greatest triumph in 1803 when the United States bought the Louisiana territory from France. Louisiana, which had been a French Province since the seventeenth century, had been ceded to Spain in 1762 at the end of the French and Indian War. Napoleon had re-acquired the North American territory for France in 1800, but mounting debts from his failed attempt to reconquer Haiti (which in 1804 became the second former colony in the Americas to achieve independence from Europe and the only nation ever established by former slaves) and the prospect of a new war with Britain convinced the Emperor of the French to give up his ambition to return France to the Americas. For $15 million—a bargain price, considering the 828,000 square miles of land involved—the Louisiana Purchase greatly enhanced the Jeffersonian vision of the United States as an agrarian republic in which yeomen farmers would work the land. The United States doubled in size. Initially, Jefferson had only hoped to buy the city of New Orleans bolster trade in the West, seeing the port on the delta of the Mississippi River (then the western boundary of the United States) as crucial to America’s agricultural commerce. In his mind, farmers would send their produce down the Mississippi River to New Orleans, where it could be put on ships or sold to European traders. When Spain had controlled New Orleans the United States had been allowed to traffic goods in the port without paying customs duties. Under French control of the city, the United States lost its right to deposit goods free in the port. Jefferson instructed Robert Livingston, the American envoy to France, to secure access to New Orleans, sending James Monroe to France to add additional pressure. The timing proved advantageous. Napoleon’s plan to make Louisiana and the Mississippi Valley a French-controlled breadbasket for Haiti, the most profitable sugar island in the world, was clearly failing. The emperor agreed to the sale in early 1803.

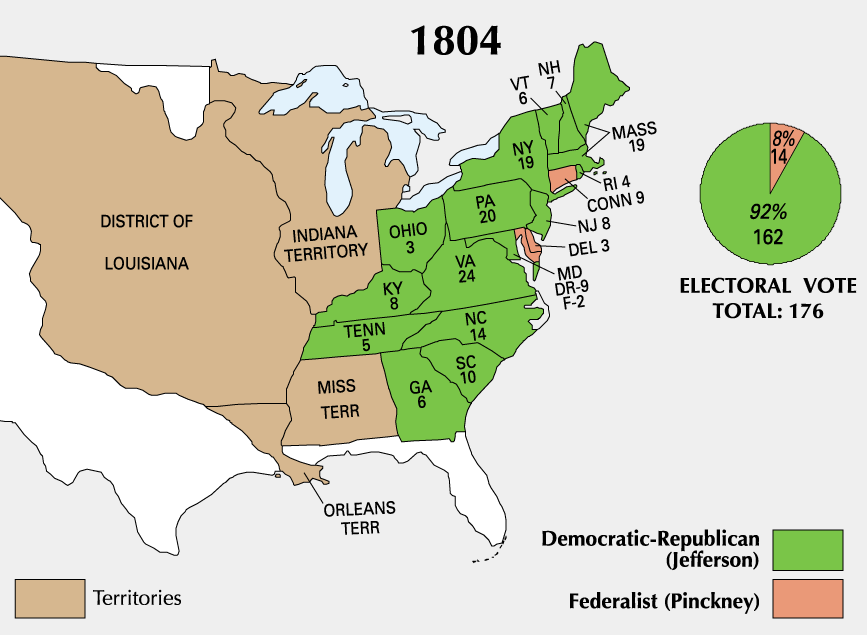

The Louisiana Purchase helped Jefferson win reelection in 1804 by a landslide. Of 176 electoral votes cast, all but 14 went to Jefferson. The great expansion of the United States did have its critics, however, especially northerners who feared both the addition of more slave states and reduced representation of their interests inCongress. And under a strict interpretation of the Constitution, it remained unclear whether President Jefferson had actually possessed the legal authority to add territory in this fashion. But the vast majority of citizens cheered the vast increase in the size and apparent importance of the republic. For slaveholders, new western lands would be a boon; for slaves, the Louisiana Purchase threatened to entrench their suffering further.

France and England continued their conflict in Europe and on the high seas during the Napoleonic Wars that raged between 1803 and 1815. Both declared open season on American ships, which they seized regularly. England was the major offender, the Royal Navy following a long-standing practice of “impressing” American sailors into its service. The issue came to a head in 1807 when the British warship HMS Leopard opened fire on a U.S. naval ship off the coast of Norfolk Virginia. The British boarded the ship and took four sailors. Having little power to force Britain to stop, Jefferson responded to the crisis with a sweeping ban on trade. The Embargo Act of 1807 prohibited American ships from leaving their ports until Britain and France stopped seizing them on the high seas. In early January, the Act was amended to include fishing boats, coastal traders, and whalers. As a result of the embargo, American commerce came to a near-total halt. The logic behind the embargo was that cutting off all trade would so severely damage the British and French economies that the seizures at sea would end. However, while the embargo did have some economic impact on the Britain, American commercial interests suffered more. The embargo hurt American farmers in addition to merchants, and seaport cities experienced increased unemployment and a rise in bankruptcies. American business activity declined by 75 percent from 1808 to 1809.

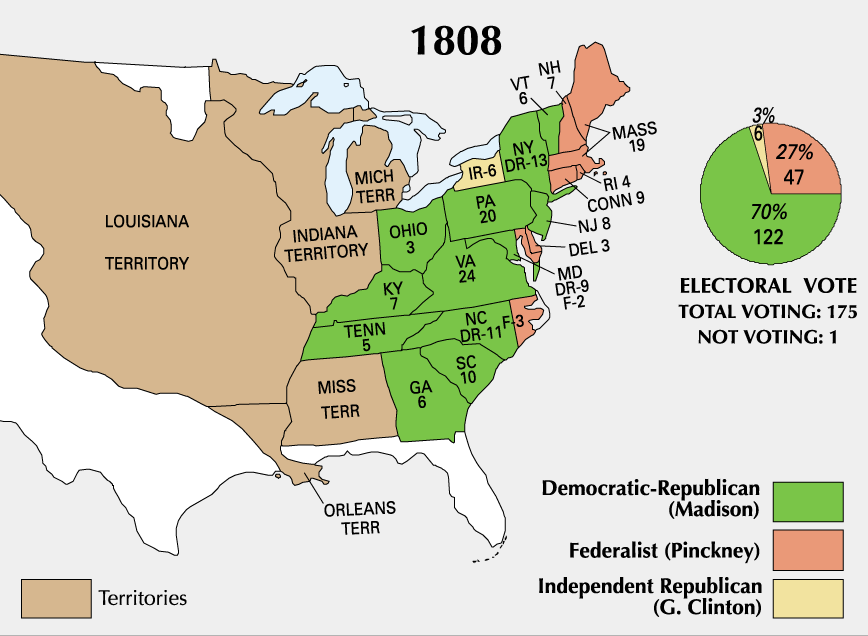

Enforcement of the embargo proved very difficult, especially in the states bordering British Canada. Smugglers’ Notch in Vermont, for example, earned its name from illegal trade with British Canada. President Jefferson attributed the problems with the embargo to lax enforcement. British merchants shifted their focus to South America and were actually happy to have less competition from American merchants. Critics of Jefferson observed that the champion of a small government that stayed out of citizens’ affairs was assuming extraordinary coercive powers to try to enforce his embargo. At the very end of his second term, Jefferson relented and signed the Non-Intercourse Act of 1808, lifting the unpopular embargoes on trade except with Britain and France. In the election of 1808, American voters elected another Democratic-Republican, James Madison. The Federalists again nominated South Carolinian Charles C. Pinckney, whom Jefferson had beaten decisively in 1804. Although Pinkney again did poorly in the South against the Virginian Madison, he did manage to win the Federalist-leaning New England states of Massachusetts, Rhode Island, Connecticut, and New Hampshire. President Madison inherited Jefferson’s foreign policy problems with Britain and France. Most people in the United States, especially those in the West, saw Great Britain as a major problem.