112 The French Revolution (1792)

My Dear General [Washington],

I have been called from the army to this capital for a conference between the two other generals, the ministers, and myself, and am about returning to my military post. The coalition between the continental powers respecting our affairs is certain and will not be broken by the Emperor’s death. But although warlike preparations are going on it is very doubtful whether our neighbors will attempt to stifle so very catching a thing as liberty.

The danger for us lies in our state of anarchy owing to the ignorance of the people, the number of non-proprietors, the jealousy of every governing measure. All which inconveniences are worked up by designing men or aristocrats in disguise, but both extremely tend to defeat our ideas of public order. Do not believe however the exaggerated accounts you may receive, particularly from England. That liberty and equality will be preserved in France, there is no doubt. In case there were, you well know that I would not, if they fall, survive them.

But you may be assured that we shall emerge from this unpleasant situation either by an honorable defense or by internal improvements. How far this constitution of ours insures a good government has not been as yet fairly experienced. This only we know, that it has restored to the people their rights, destroyed almost every abuse, and turned French vassalage and slavery into national dignity and the enjoyment of those faculties which nature has given and society ought to insure.

Give me leave to you alone to offer an observation respecting the late choice of the American ambassador. You know I am personally a friend to Gouverneur Morris and ever as a private man have been satisfied with him. But the aristocratic and indeed counter-revolutionary principles he has professed unfitted him to be the representative of the only nation whose politics have a likeness to ours, since they are founded on the plan of a representative democracy. This I may add, that surrounded with enemies as France is, it looks as if America was preparing for a change in this government. Not only that kind of alteration which the democrats may wish for and bring about, but the wild attempts of aristocracy, such as the restoration of a noblesse, a House of Lords, and such other political blemishes which, while we live, cannot be reestablished in France. I wish we had an elective Senate, a more independent set of judges, and a more energetic administration. But the people must be taught the advantages of a firm government before they reconcile it to their ideas of freedom and can distinguish it from the arbitrary systems which they have just got over. You see, my dear General, I am not an enthusiast for every part of our constitution, although I love its principles which are the same as those of the United States except the hereditary character of the president of the executive, which I think suitable to our circumstances. But I hate everything like despotism and aristocracy and I cannot help wishing the American and French principles were in the heart and on the lips of the American ambassador in France. This I mention to you alone.

There have been changes in the ministry. The King has chosen his council from the most violent popular party in the Jacobin club, a Jesuitic institution more fit to make deserters from our cause than converts to it. The new ministers however, being unsuspected, have a chance to restore public order and say they will improve it. The Assembly are wild, uninformed, and too fond of popular applause. The King, slow and rather backward in his daily conduct, although now and then he acts full well. But upon the whole it will do and the success of our revolution cannot be questioned.

My command extends on the frontiers from Givet to Bitche. I have sixty thousand men, a number that is increasing now, as young men pour in from every part of the empire to fill up the regiments. This voluntary recruiting shows a most patriotic spirit. I am going to encamp thirty thousand men, with a detached corps in an entrenched camp. The remainder will occupy the fortified places. The armies of Maréchals Luckner and Rochambeau are inferior to mine because we have sent many regiments to the southward. But in case we have a war to undertake, we may gather respectable forces.

Our emigrants are beginning to come in. Their situation abroad is miserable and in case ever we quarrel with our neighbors, they will be out of the question. Our paper money has been of late rising very fast. Manufactures of every kind are much employed. The farmer finds his cares alleviated and will feel the more happy under our constitution, as the Assembly are going to give up their patronage of one set of priests. You see that, although we have many causes to be as yet unsatisfied, we may hope everything will by and by come right. Licentiousness under the mask of patriotism is our greatest evil, as it threatens property, tranquillity, and liberty itself. Adieu, my dear General. My best respects wait on Mrs. Washington. Remember me most affectionately to our friends and think sometimes of your respectful, loving, and filial friend,

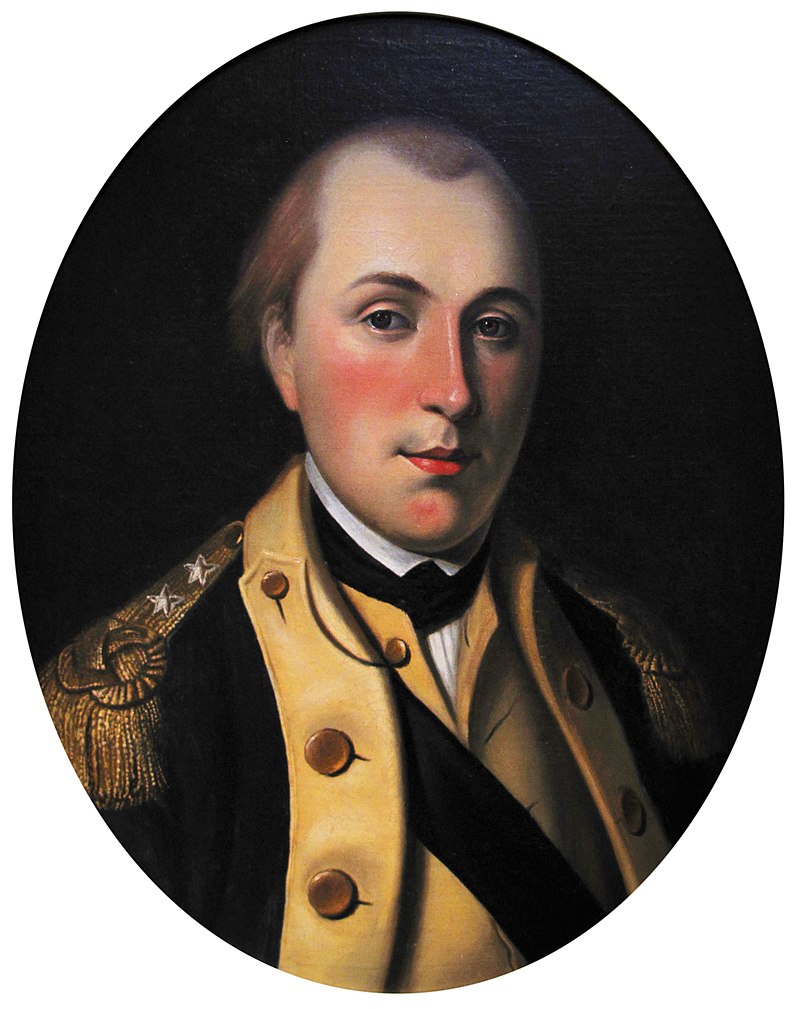

Lafayette.

Source: Letter from the Marquis de Lafayette to George Washington, in Washington’s Writings (edited by Jared Sparks, 1836), X, Appendix, 502-504. https://archive.org/details/toldcontemporari03hartrich/page/302/mode/2up