49 History of the Pilgrims (1702)

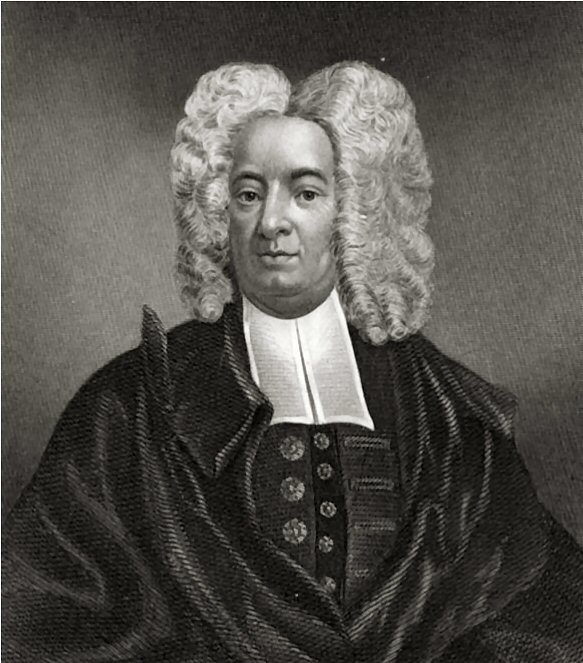

Over 80 years after the establishment of Plymouth and more than 70 since Boston, the Massachussets-born Puritan minister, Cotton Mather, wrote an ecclesiastical history of New England that he titled Magnalia Christi Americana (the great works of Christ in America). In it he described the Pilgrims’ arrival on Cape Cod and their early encounters with the natives, whom Mather claimed had been cleared from the region by Providence.

Their design was to have sat down some where about Hudson’s River, but some of their neighbors in Holland having a mind themselves to settle a plantation there, secretly and sinfully contracted with the master of the ship employed for the transportation of these our English exiles, by a more northerly course to put a trick upon them. ‘Twas in the pursuance of this plot that not only the goods, but also the lives of all on board were now hazarded by the ships falling among the shoals of Cape Cod where they were so entangled among dangerous breakers thus late in the year, that the company, got at last into the Cape Harbor, broke off their intentions of going any further. And yet, this false-dealing proved a safe-dealing for the good people against whom it was used. Had they been carried according to their desire unto Hudson’s River, the Indians in those parts were at this time so many and so mighty and so sturdy, that in probability all this little feeble number of Christians had been massacred by these bloody savages, as not long after some others were. Whereas the good hand of God now brought them to a country wonderfully prepared for their entertainment by a sweeping mortality that had lately been among the natives.

The Indians in these parts had newly, even about a year or two before, been visited with such a prodigious pestilence as carried away not a tenth, but nine parts of ten, (yea, ’tis said, nineteen of twenty) among them, so that the woods were almost cleared of those pernicious creatures, to make room for a better growth. Those infidels were consumed in such vast multitudes, that our first planters found the land almost covered with their unburied carcasses. And they that were left alive were smitten into awful and humble regards of the English.

Inexpressible the hardships to which this chosen generation was now exposed! The penetrating arrows of cold, feathered with nothing but snow and pointed with hail. And the days left them to behold the frost-bitten and weather-hardened face of the earth, were grown shorter than the nights, wherein they had yet more trouble to get shelter from the increasing injuries of the frost and weather. But these believers in our primitive times were more afraid of the barbarous people among whom they were now cast, than they were of the rain or cold. These barbarians were at the first so far from accommodating them with bundles of sticks to warm them, that they let fly other sorts of sticks (that is to say, arrows) to wound them. And the very looks and shouts of those grim savages had not much less of terror in them, than if they had been so many devils.

Hereupon they sent ashore to look [for] a convenient seat for their intended habitation. And while the carpenter was fitting of their shallop, sixteen men tendered themselves to go by land on the discovery. Accordingly on Nov. 16th, 1620, they made a dangerous adventure, following five Indians whom they spied flying before them into the woods for many miles. From whence, after two or three days ramble, they returned with some ears of Indian Corn, but with a poor and small encouragement as unto any situation [location]. When the shallop was fitted, about thirty more went in it upon a further discovery, who prospered little more than only to find a little Indian Corn, and bring to the company some occasions of doubtful debate, whether they should here fix their stakes. Yet these expeditions on discovery had this one remarkable smile of Heaven upon them; that being made before the snow covered the ground, they met with some Indian Corn and this Corn served them for seed in the Spring following, which else they had not been seasonably furnished withal. So that it proved, in effect, their deliverance from the terrible famine.

At last, on Dec. 6, 1620, they manned the shallop with about eighteen or twenty hands and went out upon a third discovery. So bitterly cold was the season that the spray of the sea lighting on their clothes,

glazed them with an immediate congelation. Yet they kept cruising about the bay of Cape-Cod and that night they got safe down the bottom of the bay. There they landed and there they tarried that night, and

unsuccessfully ranging about all the next day, at night they made a little barricade of boughs and logs, wherein the most weary slept. The next morning they suddenly were surrounded with a crew of Indians who let fly a shower of arrows among them. Whereat our distressed handful of English happily recovering their arms, which they had laid by from the moisture of the weather. They vigorously discharged their muskets upon the Savages, who astonished at the strange effects of such dead-doing things as powder and shot, fled apace into the woods. But not one of ours was wounded by the Indian arrows that flew like hail about their ears and pierced through sundry of their coats; and they called the place by the name of The First Encounter. From hence they coasted along, till a horrible storm arose which tore their vessel at such a rate and threw them into the midst of such dangerous breakers, it was reckoned little short of miracle that they escaped alive. In the end they got under the lee of a small island where, going ashore, they kindled fires for their succor against the wet and cold. On the next day they sounded the harbor and found it fit for shipping. They visited the main land also and found it accommodated with pleasant fields and brooks. So they resolved that they would here pitch their tents; and sailing up to the town of Plymouth, (by the Indians ’twas called Patuxet) on the twenty-fifth day of December they began to erect the first House that ever was in that memorable town; and yet it was not long before an unhappy accident burnt unto the ground their house. After this they soon went upon the building of more little cottages and upon the settling of good laws for the better governing of such as were to inhabit those cottages. They then resolved that until they could be further strengthened in their settlement by the authority of England, they would be governed by rulers chosen from among themselves, who were to proceed

according to the laws of England and such other by-laws, as by common consent should be judged necessary for the circumstances of the Plantation.

If the reader would know how these good people fared the rest of the melancholy winter, let him know that besides the exercises of religion, with other work enough, there was the care of the sick to take up no little part of their time. ‘Twas a most heavy trial of their patience, whereto they were called the first winter of this their pilgrimage. The hardships which they encountered were attended with and productive of deadly sicknesses which in two or three months carried off more than half their company. There died sometimes two, sometimes three in a day, till scarcely fifty of them were left alive. And of those fifty, sometimes there were scarce five well at a time to look after the sick. Yet there was this remarkable providence further in the circumstances of this mortality, that if a disease had not more easily fetched so many of this number away to Heaven, a famine would probably have destroyed them all, before their

expected supplies from England were arrived. But what a wonder was it that all the bloody savages far and near did not cut off this little remnant! They saw no Indians all the winter long, but such as at the

first sight always ran away. Yea, they quickly found that God had so turned the hearts of these barbarians, as more to fear than to hate his people thus cast among them. This blessed people was as a little flock of kids, while there were many nations of Indians left still as kennels of wolves in every corner of the country. And this little flock suffered no damage by those rabid wolves.

Source: Cotton Mather, Magnalia Christi Americana, 1702, 1853. 50-53. https://archive.org/details/cihm_44870/page/n89/mode/2up