164 On the Duty of Civil Disobedience (1849)

I heartily accept the motto, “That government is best which governs least”; and I should like to see it acted up to more rapidly and systematically. Carried out, it finally amounts to this, which also I believe—”That government is best which governs not at all”. And when men are prepared for it, that will be the kind of government which they will have. Government is at best but an expedient, but most governments are usually and all governments are sometimes inexpedient. The objections which have been brought against a standing army, and they are many and weighty and deserve to prevail, may also at last be brought against a standing government. The standing army is only an arm of the standing government.

I heartily accept the motto, “That government is best which governs least”; and I should like to see it acted up to more rapidly and systematically. Carried out, it finally amounts to this, which also I believe—”That government is best which governs not at all”. And when men are prepared for it, that will be the kind of government which they will have. Government is at best but an expedient, but most governments are usually and all governments are sometimes inexpedient. The objections which have been brought against a standing army, and they are many and weighty and deserve to prevail, may also at last be brought against a standing government. The standing army is only an arm of the standing government.

The mass of men serve the state thus, not as men mainly but as machines with their bodies. In most cases there is no free exercise whatever of the judgement or of the moral sense, but they put themselves on a level with wood and earth and stones. And wooden men can perhaps be manufactured that will serve the purpose as well. Such command no more respect than men of straw or a lump of dirt. They have the same sort of worth only as horses and dogs. Yet such as these even are commonly esteemed good citizens. Others—as most legislators, politicians, lawyers, ministers, and office-holders—serve the state chiefly with their heads and as they rarely make any moral distinctions. They are as likely to serve the devil without intending it, as God. A very few—as heroes, patriots, martyrs, reformers in the great sense, and men—serve the state with their consciences also and so necessarily resist it for the most part. And they are commonly treated as enemies by it.

How does it become a man to behave toward the American government today? I answer that he cannot without disgrace be associated with it. I cannot for an instant recognize that political organization as my government which is the slave’s government also. When a sixth of the population of a nation which has undertaken to be the refuge of liberty are slaves and a whole country is unjustly overrun and conquered by a foreign army and subjected to military law, I think that it is not too soon for honest men to rebel and revolutionize. What makes this duty the more urgent is that fact that the country so overrun is not our own, but ours is the invading army.

Practically speaking, the opponents to a reform in Massachusetts are not a hundred thousand politicians at the South but a hundred thousand merchants and farmers here, who are more interested in commerce and agriculture than they are in humanity and are not prepared to do justice to the slave and to Mexico. I quarrel not with far-off foes but with those who, near at home, co-operate with and do the bidding of those far away, and without whom the latter would be harmless. We are accustomed to say that the mass of men are unprepared, but improvement is slow because the few are not as materially wiser or better than the many. There are thousands who are in opinion opposed to slavery and to the war, who yet in effect do nothing to put an end to them. Who esteeming themselves children of Washington and Franklin, sit down with their hands in their pockets and say that they know not what to do, and do nothing. Who even postpone the question of freedom to the question of free trade and quietly read the prices-current along with the latest advices from Mexico after dinner, and it may be, fall asleep over them both.

All voting is a sort of gaming like checkers or backgammon, with a slight moral tinge to it. A playing with right and wrong, with moral questions, and betting naturally accompanies it. The character of the voters is not staked. I cast my vote perchance as I think right, but I am not vitally concerned that that right should prevail. I am willing to leave it to the majority. Its obligation therefore never exceeds that of expediency. Even voting for the right is doing nothing for it. It is only expressing to men feebly your desire that it should prevail. A wise man will not leave the right to the mercy of chance nor wish it to prevail through the power of the majority. There is but little virtue in the action of masses of men. When the majority shall at length vote for the abolition of slavery, it will be because they are indifferent to slavery or because there is but little slavery left to be abolished by their vote. They will then be the only slaves.

Those who while they disapprove of the character and measures of a government, yield to it their allegiance and support are undoubtedly its most conscientious supporters and so frequently the most serious obstacles to reform. Some are petitioning the state to dissolve the Union, to disregard the requisitions of the President. Why do they not dissolve it themselves—the union between themselves and the state—and refuse to pay their quota into its treasury? Do not they stand in same relation to the state that the state does to the Union? And have not the same reasons prevented the state from resisting the Union which have prevented them from resisting the state?

Action from principle, the perception and the performance of right changes things and relations; it is essentially revolutionary. Unjust laws exist, shall we be content to obey them? Or shall we endeavor to amend them and obey them until we have succeeded? Or shall we transgress them at once? Men generally, under such a government as this, think that they ought to wait until they have persuaded the majority to alter them. They think that if they should resist, the remedy would be worse than the evil. But it is the fault of the government itself that the remedy is worse than the evil. It makes it worse. Why is it not more apt to anticipate and provide for reform?

I do not hesitate to say that those who call themselves Abolitionists should at once effectually withdraw their support both in person and property from the government of Massachusetts and not wait till they constitute a majority of one before they suffer the right to prevail through them. Moreover, any man more right than his neighbors constitutes a majority of one already.

Under a government which imprisons unjustly, the true place for a just man is also a prison. The proper place today, the only place which Massachusetts has provided for her freer and less despondent spirits, is in her prisons. To be put out and locked out of the State by her own act, as they have already put themselves out by their principles. It is there that the fugitive slave, and the Mexican prisoner on parole, and the Indian come to plead the wrongs of his race should find them. On that separate but more free and honorable ground where the State places those who are not with her, but against her—the only house in a slave State in which a free man can abide with honor.

They who assert the purest right and consequently are most dangerous to a corrupt State commonly have not spent much time in accumulating property. To such the State renders comparatively small service and a slight tax is wont to appear exorbitant, particularly if they are obliged to earn it by special labor with their hands. If there were one who lived wholly without the use of money, the State itself would hesitate to demand it of him. But the rich man is always sold to the institution which makes him rich. Absolutely speaking, the more money, the less virtue.

When I converse with the freest of my neighbors I perceive that the long and the short of the matter is that they cannot spare the protection of the existing government and they dread the consequences to their property and families of disobedience to it. The state never intentionally confronts a man’s sense, intellectual or moral, but only his body, his senses. It is not armed with superior wit or honesty, but with superior physical strength. I was not born to be forced.

Is it not possible to take a step further towards recognizing and organizing the rights of man? There will never be a really free and enlightened state until the state comes to recognize the individual as a higher and independent power from which all its own power and authority are derived, and treats him accordingly. I please myself with imagining a state at last which can afford to be just to all men and to treat the individual with respect as a neighbor.

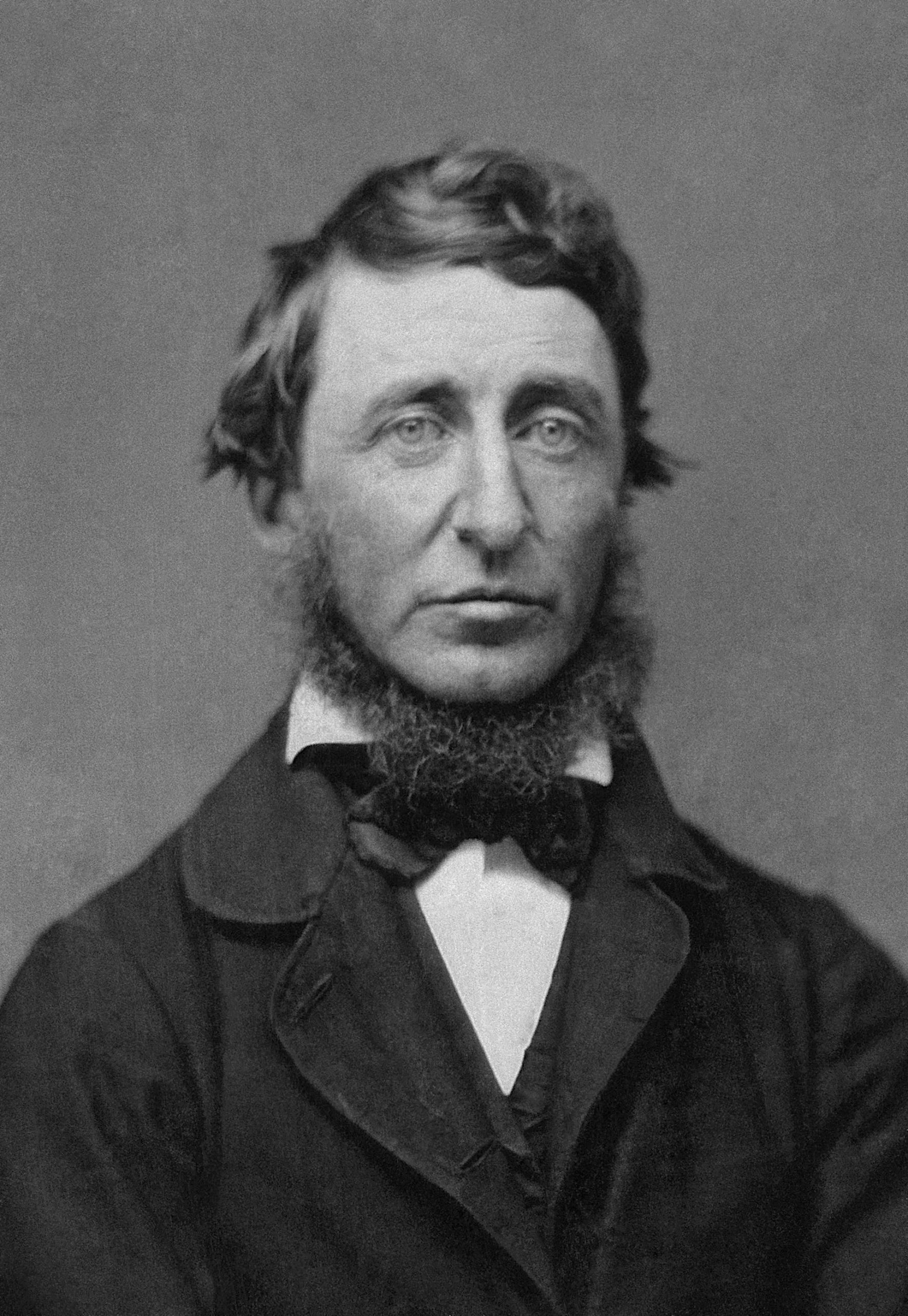

Source: Henry David Thoreau (1849). Original title: “Resistance to Civil Government”. http://www.historyisaweapon.com/defcon1/thoreaucivildisobe.html