11. Jacksonian Democracy

In the years before the Civil War, American planters in the South continued to grow Chesapeake tobacco and Carolina rice as they had in the colonial era. Cotton, however, emerged as the antebellum South’s major commercial crop, eclipsing tobacco, rice, and sugar in economic importance. By 1860, the region produced two-thirds of the world’s cotton. In 1793, Eli Whitney had revolutionized production with the cotton gin which dramatically reduced the time it took to process raw cotton, As a commodity, cotton also had the advantage of being easily stored and transported. Demand in the industrial textile mills of Great Britain and New England seemed inexahustible. Southern cotton, picked and processed by American slaves, upheld the wealth and power of the planter elite while it fueled the nineteenth-century Industrial Revolution in both the United States and Great Britain.

Almost no cotton was grown in the United States in 1790 when the first U.S. Census was conducted. Following the War of 1812, cotton became the key cash crop of the southern economy and the most important American commodity. By 1850, 1.8 million of the 3.2 million slaves in the country’s fifteen slave states produced cotton and by 1860, slave labor produced over two billion pounds of cotton annually. American cotton made up two-thirds of the global supply, and production continued to increase. By the time of the Civil War, South Carolina politician James Hammond confidently proclaimed that the North could never threaten the South because “cotton is king.”

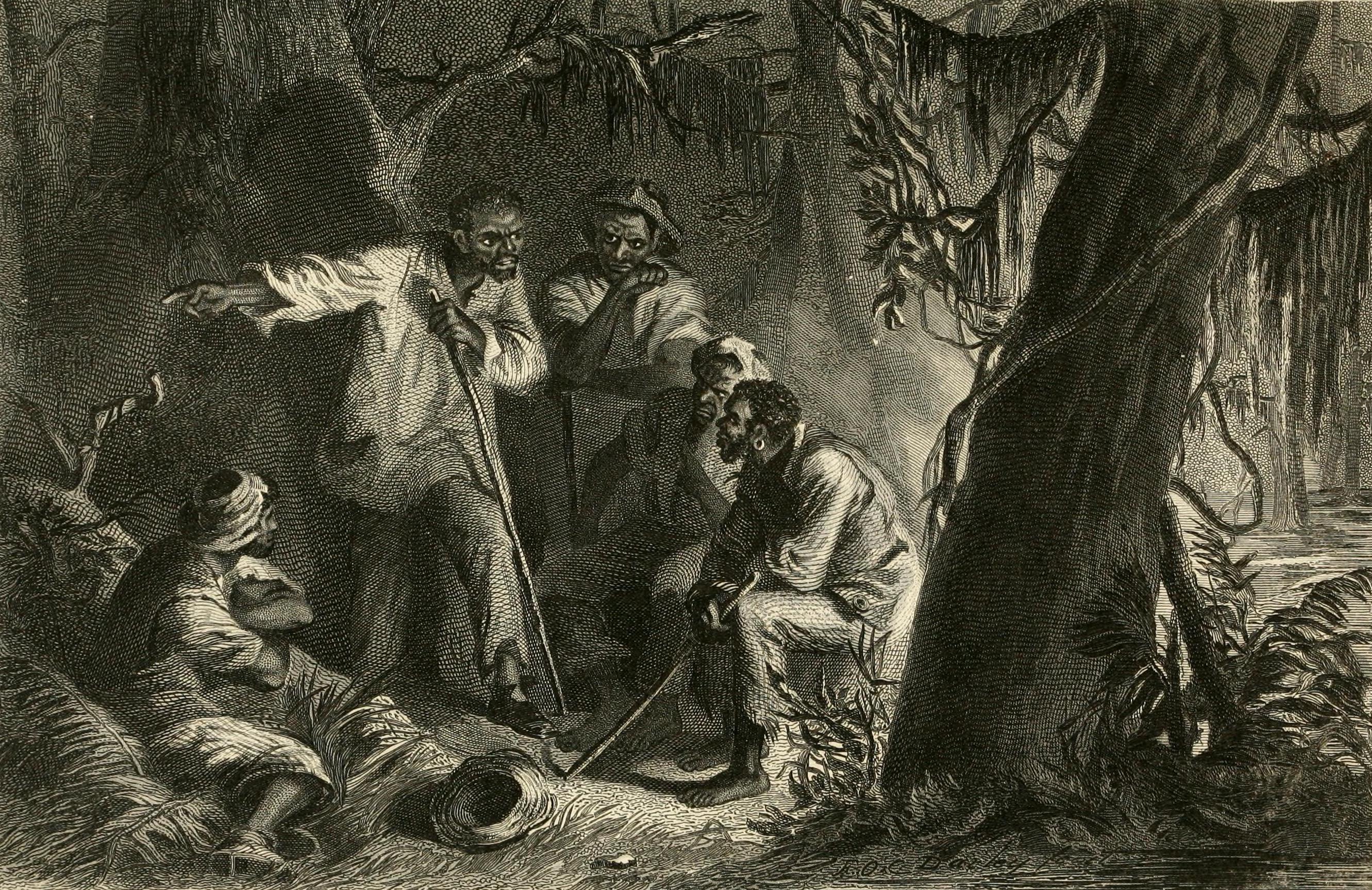

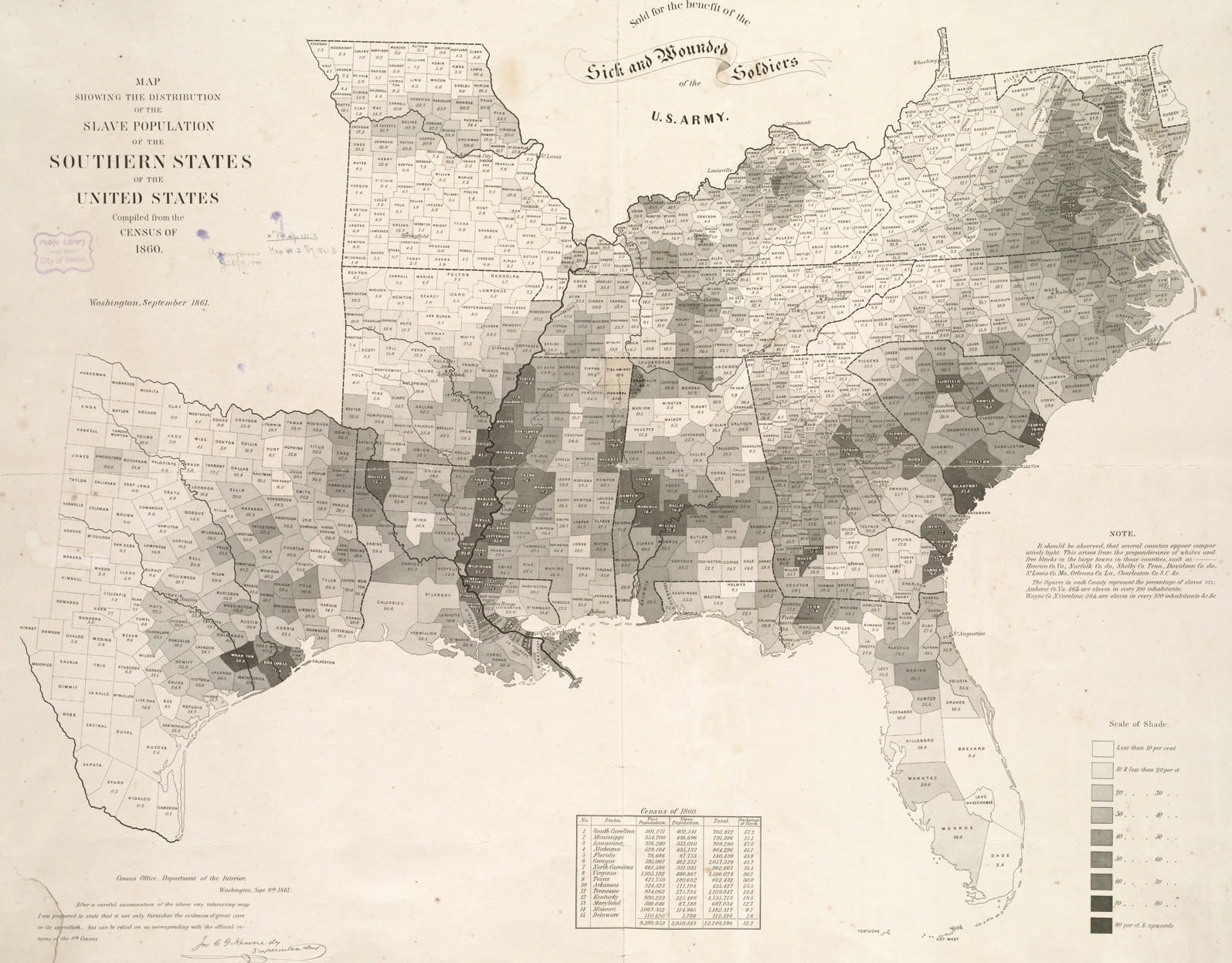

The crop grown in the South was a hybrid known as Petit Gulf cotton that grew extremely well in the Mississippi River Valley as well as in other states like Texas. Whenever new slave states entered the Union, white slaveholders sent armies of slaves to clear land to grow the lucrative crop. The phrase “to be sold down the river,” used by Harriet Beecher Stowe in her 1852 novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin, refers to this forced migration from the upper southern states to the Deep South, lower on the Mississippi, to grow cotton. The slaves forced to build James Hammond’s cotton kingdom with their labor started by clearing the land. Thomas Jefferson’s agrarian vision of white yeoman farmers settling the West by single-handedly carving out small independent farms ironically proved quite different in the South. Old-growth forests and cypress swamps were cleared by slaves and readied for plowing and planting. To ambitious white planters, the new land available for cotton production seemed almost limitless and many planters leapfrogged from one area to the next, abandoning their fields every ten to fifteen years when the soil became exhausted. Slaves composed the vanguard of this American expansion to the West.

Cotton planting took place in March and April, when slaves planted seeds in rows around three to five feet apart. Over the next several months, from April to August, they carefully tended the plants and weeded the cotton rows. Beginning in August, all the plantation’s slaves worked together to pick the crop. Cotton picking occurred as many as seven times a season as the plant continued to flower and produce bolls through the fall and early winter. During the picking season, slaves worked from sunrise to sunset with a ten-minute break at lunch. Once they had brought the cotton to the gin house to be weighed, slaves then had to care for the animals and perform other chores. Indeed, slaves often maintained their own gardens and livestock, which they tended after working the cotton fields, in order to supplement their supply of food.

As the cotton industry boomed in the South, Mississippi River steamboats became a defining component of the cotton kingdom. The video clip above, from a 1937 documentary by Pare Lorentz, shows cotton bales being loaded on a riverboat as they had been for generations. Riverboats were already an important part of the transportation revolution due to their enormous freight-carrying capacity and ability to navigate shallow waterways. By 1837, there were over seven hundred steamships operating on the Mississippi and its tributaries. Major new ports developed at St. Louis, Memphis, Chattanooga, Shreveport, and other locations. By 1860, some thirty-five hundred riverboats were steaming in and out of New Orleans carrying an annual cargo of cotton worth $220 million (over $7 billion in 2019 dollars). Riverboats also came to symbolize the class and social distinctions of the antebellum age. While the decks carried the precious cargo, ornate rooms staterooms graced the interior where whites socialized in the ship’s saloons and dining halls while black slaves served them.

New Orleans had been part of the French Louisiana Territory the United States purchased in 1803. President Jefferson had been interested in acquiring the important port even before Napoleon offered the entire territory. In the first half of the nineteenth century, New Orleans rose to even greater prominence with the cotton boom. Steamboats delivered cotton grown on plantations throughout the South to the port at New Orleans. Initially, the bulk of American cotton went to Liverpool, England, where it was sold to British textile manufacturers. As New England textiles overtook the British industry, the South and New Orleans became rich. By 1840, New Orleans held 12 percent of the nation’s total banking capital, and visitors often commented on the great cultural diversity of the city. A visitor from New England wrote, “Truly does New-Orleans represent every other city and nation upon earth. I know of none where is congregated so great a variety of the human species.” Slaves, cotton, and the steamship transformed the city from a relatively isolated corner of North America in the eighteenth century to a thriving metropolis that rivaled New York in importance.

The South’s dependence on cotton was matched by its dependence on slaves to plant, tend, and harvest the cotton. Despite the rhetoric of the American Revolution that “all men are created equal,” slavery not only endured in the United States but was the very foundation of the country’s economic success. Cotton and slavery occupied a central place in the nineteenth-century economy. Importing slaves into the United States was outlawed by Congress in 1808, but owning slaves remained legal. At the same time, falling tobacco prices caused a shift to wheat farming in the upper South. Raising wheat was much less labor-intensive than tobacco – in fact, the yeoman farmers Jefferson had imagined spreading westward grew plenty of wheat with no slaves at all. Rather than competing with farmers in the North and Midwest, slaveowners in states like Virginia, Maryland, and Kentucky went into the business of raising and selling slaves to the cotton plantations of the Deep South. As many as a million slaves were “sold down the river” in the domestic slave trade during the first half of the nineteenth century, generating immense fortunes for already-wealthy slaveowners in the upper South.

SOLOMON NORTHUP REMEMBERS THE NEW ORLEANS SLAVE MARKET

Solomon Northup was a free black man living in Saratoga, New York, when he was kidnapped and sold into slavery in 1841. He later escaped and wrote a book about his experiences, Twelve Years a Slave. Narrative of Solomon Northup, a Citizen of New-York, Kidnapped in Washington City in 1841 and Rescued in 1853, which was made into the 2013 Academy Award–winning film. This excerpt derives from Northup’s description of being sold in New Orleans, along with fellow slave Eliza and her children Randall and Emily.

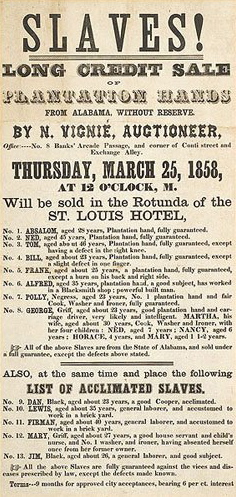

One old gentleman, who said he wanted a coachman, appeared to take a fancy to me…The same man also purchased Randall. The little fellow was made to jump, and run across the floor, and perform many other feats, exhibiting his activity and condition. All the time the trade was going on, Eliza was crying aloud, and wringing her hands. She besought the man not to buy him, unless he also bought her self and Emily…Freeman turned round to her, savagely, with his whip in his uplifted hand, ordering her to stop her noise, or he would flog her. He would not have such work—such snivelling; and unless she ceased that minute, he would take her to the yard and give her a hundred lashes…Eliza shrunk before him, and tried to wipe away her tears, but it was all in vain. She wanted to be with her children, she said, the little time she had to live. All the frowns and threats of Freeman, could not wholly silence the afflicted mother.

During the first half of the nineteenth century, industrialization brought changes to both the production and the consumption of goods in the United States. Some southerners believed that their reliance on a single cash crop and its use of slaves to produce it gave the South economic independence and made them immune from the effects of these changes. Actually, producing cotton brought the South more firmly into larger American and Atlantic markets. Northern mills depended on the South for supplies of raw cotton. And between 1820 and 1860, approximately 80 percent of the global cotton supply was produced in the United States. Nearly all the exported cotton was shipped to Great Britain, making the powerful British Empire increasingly dependent on American cotton and southern slavery.

The power of cotton on the world market may have brought wealth to the South, but it also increased its economic dependence on other countries and other parts of the United States. Much of the corn and pork that slaves consumed came from farms in the West. Cheap clothing and shoes worn by slaves were manufactured in the North. The North also supplied furnishings for the homes of both wealthy planters and members of the middle class. Nearly all the accoutrements of comfortable living for southern whites, such as carpets, lamps, dinnerware, upholstered furniture, books, and musical instruments, were made in either the North or Europe. Southern planters also borrowed money from banks in northern cities, and in the southern summers, took advantage of the developments in transportation to travel to resorts at Saratoga, New York; Litchfield, Connecticut; and Newport, Rhode Island.

Southern whites frequently relied upon the idea of paternalism, that white slaveholders acted in the best interests of slaves, to justify the existence of slavery. Slaveholders claimed to feel great responsibility for their slaves’ care, feeding, discipline, and even their Christian morality. Some even suggested that their slaves were better off in the South than they had been as “savage” and “heathen” free people in Africa. These rationalizations grossly misrepresented the reality of slavery, which was a dehumanizing, traumatizing, and horrifying human disaster and crime against humanity. And slaves were not always passive victims of their conditions; they often found ways to resist their shackles and develop their own communities and cultures.

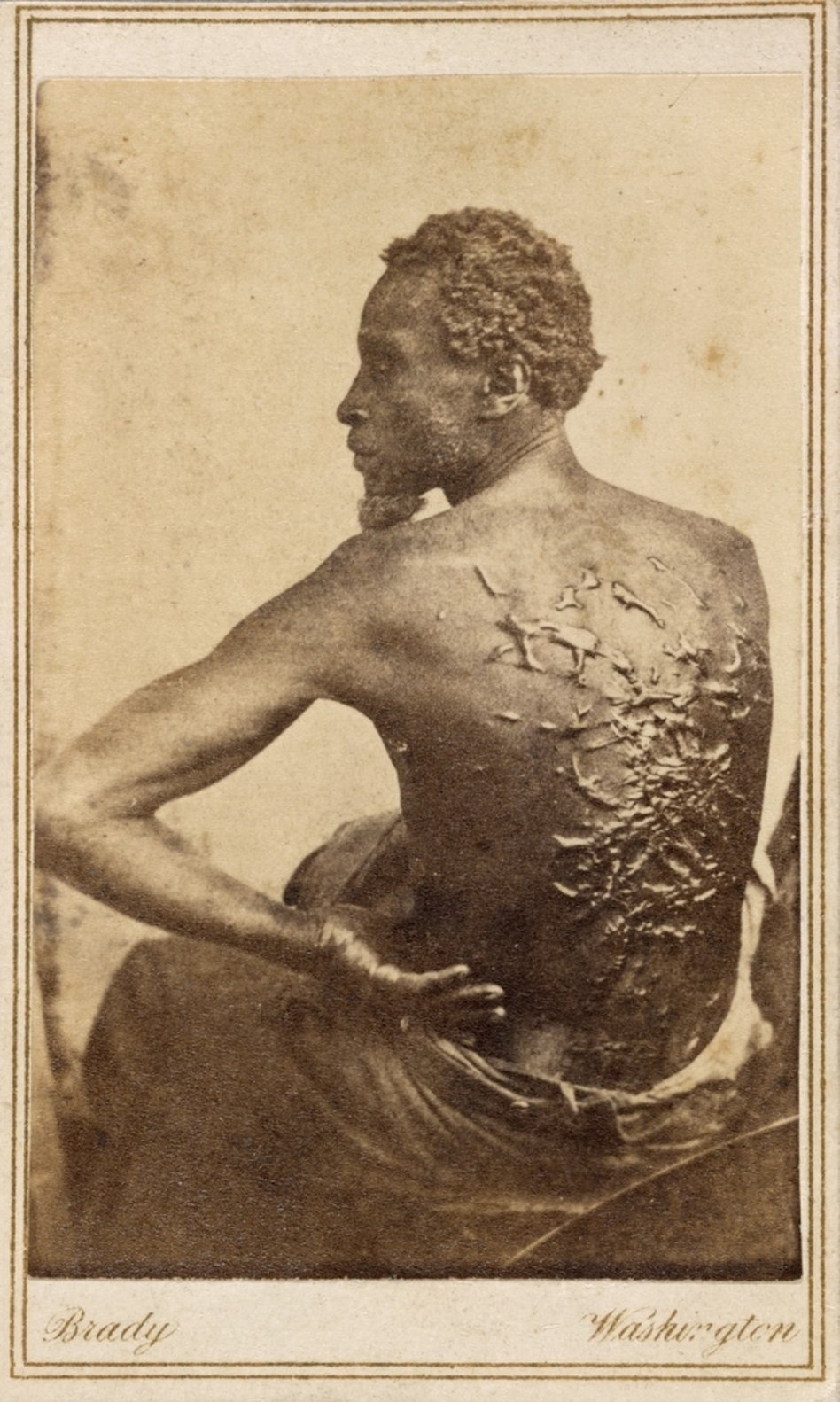

Slaves often used notions of paternalism to their advantage, finding opportunities to resist and winning a degree of freedom and autonomy. For example, some slaves took advantage of slaveholders’ racism by hiding their intelligence and feigning childishness and stupidity. Slaves could slow down the workday and sabotage the system in small ways by “accidentally” breaking tools. A slaveholder who believed his slaves were unsophisticated and childlike might conclude these incidents were accidents rather than rebellions. Some slaves engaged in more dramatic forms of resistance, such as poisoning their masters slowly. But subversion and sabotage were dangerous. Slaves hoping to gain preferential treatment sometimes informed slaveholders about planned slave rebellions, hoping to earn the slaveholder’s gratitude and more lenient treatment. Slaveholders used both psychological coercion and physical violence to prevent slaves from disobeying their wishes. The lash, while the most common form of punishment, was effective but sometimes left slaves incapacitated or even dead. Slaveholders also used punishment gear like neck braces, balls and chains, leg irons, and spurs. But often, the most effective way to intimidate slaves was to threaten to sell them. Slaves lived in constant terror of both physical violence and separation from family and friends.

Under southern law, slaves could not marry. But many slaveholders allowed unions to promote the birth of children and to foster harmony on plantations. Some even forced slaves to form unions, anticipating the birth of more children and greater profits from them. Slaveholders sometimes allowed slaves to choose their own partners, but they could also veto a match. Slave couples always faced the prospect of being sold away from each other, and, once they had children, the horrifying reality that their children could be sold and sent away at any time.

Slave parents tried to show their children the best ways to survive under slavery, teaching them to be discreet, submissive, and guarded around whites. Parents also taught children more subversive lessons through the stories they told. Popular stories among slaves included tales of tricksters, sly slaves, or animals like Brer Rabbit who outwitted powerful but stupid antagonists. Such stories provided comfort in humor and conveyed the slaves’ sense of the wrongs of slavery. Slaves’ work songs commented on the harshness of their life and often hid double meanings:a literal meaning that whites would not find offensive and a deeper meaning for slaves.

African beliefs, including ideas about the spiritual world and the importance of African healers, survived in the South as well. Whites who became aware of non-Christian rituals among slaves often labeled such practices as witchcraft or voodoo. Among Africans, however, rituals and use of various plants by respected slave healers created connections between the African past and the American South and gave slaves a sense of community and identity. Other African customs, including traditional naming patterns, making baskets, and cultivating native African plants that had been brought to the New World, also endured. Many slaves embraced Christianity. Whites emphasized scriptural messages of obedience and patience, promising a better day awaiting slaves in heaven; but slaves focused on the uplifting message of being freed from bondage. Spiritual songs that referenced the Exodus, such as “Roll, Jordan, Roll,” allowed slaves to freely express messages of hope, struggle, and overcoming adversity.

Complicating the picture of antebellum Southern society was the existence of a large free black population. More free blacks lived in the South than in the North: roughly 261,000 lived in slave states, while 226,000 lived in northern states without slavery. Most free blacks did not live in the Deep South, but in the upper southern states of Delaware, Maryland, Virginia, North Carolina, and later Kentucky, Missouri, Tennessee, and the District of Columbia. One reason for the large number of free blacks living in slave states were the many instances of manumission that occurred after the Revolution, when many slaveholders acted on the ideal that “all men are created equal” and freed their slaves. And the transition to the staple crop of wheat, which did not require large numbers of slaves to produce, also spurred some manumissions. Another large group of free blacks in the South had been free residents of Louisiana before the 1803 Louisiana Purchase, while still other free blacks came from Cuba and Haiti.

Most free blacks in the South lived in cities, and a majority of free blacks were lighter-skinned due to interracial unions between white men and black women. Everywhere in the United States blackness had come to be associated with slavery. Both whites and those with African ancestry were acutely aware of the importance of skin color in social hierarchy. In the slaveholding South, different names described a person’s distance from full blackness. Mulattos had one black and one white parent, quadroons had one black grandparent, and octoroons had one black great-grandparent. Throughout most of American history a “one drop” rule prevailed, where a person with even a single African in her background was classified as black regardless of appearance (for example, Thomas Jefferson’s mistress Sally Hemings probably looked very much like her half-sister, Jefferson’s late wife. But Hemings was one quarter African, which made her Jefferson’s slave). Even though their legal status was the same, lighter-skinned blacks often looked down on their darker counterparts, an indication of the ways in which both whites and blacks internalized the racism of the age.

Slaves resisted in small ways every day, and this resistance often led to mass uprisings. Although southern society tried to hide slave resistance under the fiction of paternalism, historians have documented over 250 revolts or plots involving ten or more slaves. Enslaved people understood that the chances of ending slavery through rebellion were slim and that violent resistance would result in massive retaliation. Many feared the risk that rebelling would pose to their families, but conditions were often so unbearable that rebellions went ahead anyway. White slaveholders, outnumbered by slaves in most of the South, constantly feared uprisings and took drastic steps, including torture and mutilation, whenever they believed that rebellions might be simmering. Gripped by the fear of insurrection, whites often imagined revolts to be in the works even when no uprising actually happened.

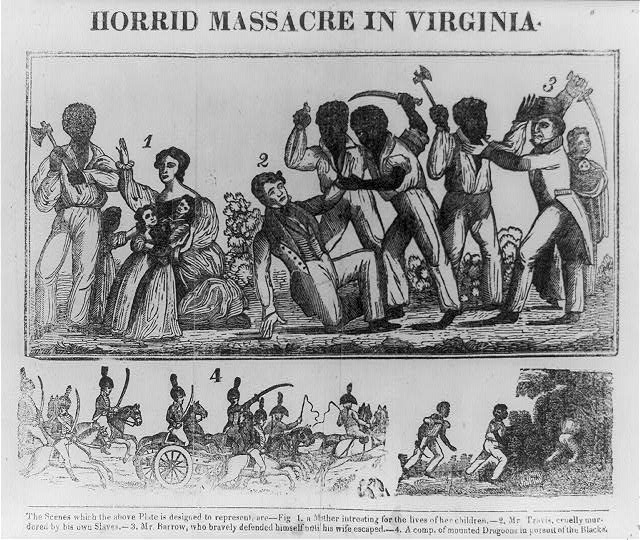

Important slave rebellions in the British North American colonies and the United States included the New York Slave Revolt of 1712, the Samba Rebellion (1731), the Stono Rebellion (1739), the New York Slave Insurrection (1741), the Mina Conspiracy (1791), the Pointe Coupée conspiracy (1794), Gabriel’s conspiracy (1800), the Igbo Landing mass suicide (1803), the Chatham Manor Rebellion (1805), the German Coast Uprising (1811), George Boxley’s Rebellion (1815), Denmark Vesey’s conspiracy (1822), Nat Turner’s Rebellion (1831), the Black Seminole Rebellion (1835-38), the Amistad ship seizure (1839), the Creole ship rebellion (1841), the Slave Revolt in the Cherokee Nation (1842), and John Brown’s raid on Harpers Ferry (1859) which included an attempt to organize a slave rebellion. One of the most traumatic for white Southerners was the revolt led by a slave named Nat Turner in 1831 in Southampton County, Virginia. Turner had suffered not only from personal enslavement, but also from the additional trauma of having his wife sold away from him. Bolstered by Christianity, Turner became convinced that like Christ, he should lay down his life to end slavery. Mustering his relatives and friends, he began the rebellion August 22, killing scores of whites in the county. Whites mobilized quickly and within forty-eight hours had brought the rebellion to an end. Shocked by Nat Turner’s Rebellion and aware that the use of slaves in Virginia was decreasing with the decline of tobacco, Virginia’s state legislature considered ending slavery in the state in order to provide greater security. In the end, legislators decided slavery would remain and that their state would continue to play a key role in the domestic slave trade.

Nat Turner’s Rebellion, which broke out in August 1831 in Southampton County Virginia, was one of the largest slave uprisings in American history. Nat Turner was a literate slave who was inspired by the evangelical Protestant fervor of the Second Great Awakening sweeping the republic. He preached to fellow slaves and gained a reputation among them as a prophet. Turner organized them for rebellion until an eclipse in August signaled that the appointed time had come. Turner and as many as seventy other slaves attacked their slaveholders and the slaveholders’ families, killing about sixty-five people. Turner eluded capture until late October, when he was caught, hanged, beheaded, and quartered. Virginia executed fifty-six other slaves whom they suspected were part in the rebellion. White vigilantes murdered two hundred more as panic swept through Virginia and the rest of the South.

NAT TURNER ON HIS BATTLE AGAINST SLAVERY

Thomas R. Gray was a lawyer in Southampton, Virginia, where he visited Nat Turner in jail. He published The Confessions of Nat Turner, the leader of the late insurrection in Southampton, Va., as fully and voluntarily made to Thomas R. Gray in November 1831, after Turner had been executed.

For as the blood of Christ had been shed on this earth, and had ascended to heaven for the salvation of sinners, and was now returning to earth again in the form of dew…it was plain to me that the Saviour was about to lay down the yoke he had borne for the sins of men, and the great day of judgment was at hand…And on the 12th of May, 1828, I heard a loud noise in the heavens, and the Spirit instantly appeared to me and said the Serpent was loosened, and Christ had laid down the yoke he had borne for the sins of men, and that I should take it on and fight against the Serpent,…Ques. Do you not find yourself mistaken now? Ans. Was not Christ crucified. And by signs in the heavens that it would make known to me when I should commence the great work—and on the appearance of the sign, (the eclipse of the sun last February) I should arise and prepare myself, and slay my enemies with their own weapons.

Nat Turner’s Rebellion provoked a heated discussion in Virginia over slavery. The Virginia legislature was already in the process of revising the state constitution, and some delegates advocated for an easier manumission process. The rebellion, however, rendered that reform impossible. Virginia and other slave states recommitted themselves to the institution of slavery, and defenders of slavery in the South increasingly blamed northerners for provoking their slaves to rebel.

The selling of slaves was a major business enterprise throughout the history of the South, representing a key part of the economy. Beginning in the colonial period, when Thomas Jefferson wrote about the profits that could be made on the “natural increase” produced by enslaved women, white men invested substantial sums in slaves and carefully calculated the annual returns they could expect from selling a slave’s children. The domestic slave trade was highly profitable and between 1820 and 1860, white American traders sold a million or more slaves in the domestic slave market. Groups of slaves were transported by ship from places like Virginia, a state that specialized in raising slaves for sale, to New Orleans, where they were sold to planters in the Mississippi Valley. Other slaves made the overland trek in chains from older states like North Carolina to new and booming Deep South states like Alabama.

New Orleans had the largest slave market in the United States. A healthy young male slave in the 1850s could be sold for $1,000 (approximately $33,000 in 2019 dollars), and by the 1850s demand for slaves reached an all-time high, and prices therefore doubled. The high price of slaves in the 1850s and the inability of natural increase to satisfy demands led some southerners to demand the reopening of the international slave trade, a movement that caused a rift between the Upper South and the Lower South. Whites in the Upper South who sold slaves to their counterparts in the Lower South worried that reopening the trade would lower prices and hurt their profits.

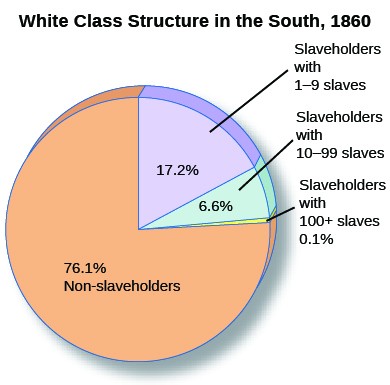

The South prospered, but its wealth was very unequally distributed. Upward social mobility did not exist for the millions of slaves who produced a good portion of the nation’s wealth, while poor southern whites hoped for a day when they might rise enough in the world to own slaves of their own. Because of the cotton boom, there were more millionaires per capita in the Mississippi River Valley by 1860 than anywhere else in the United States. However, in that same year, only 3 percent of whites owned more than fifty slaves, and two-thirds of white households in the South did not own any slaves at all. Distribution of wealth in the South became less democratic over time with fewer whites owning slaves in 1860 than in 1840.

At the top of southern white society was a planter elite comprised of two groups. In the Upper South, an aristocratic gentry, generation upon generation of whom had grown up with slavery, held a privileged place. In the Deep South, a newly-rich elite group of slaveholders had gained their wealth from cotton. Some members of this group hailed from established families in the eastern states (Virginia and the Carolinas), while others came from humbler backgrounds. South Carolinian Nathaniel Heyward, a wealthy rice planter and member of the aristocratic gentry, came from an established family and sat atop the pyramid of southern slaveholders. He amassed an enormous estate; in 1850, he owned more than eighteen hundred slaves. When he died in 1851, he left an estate worth more than $2 million (approximately $65 million in current dollars).

As cotton production increased, wealth flowed to the cotton planters whether they had inherited fortunes or were newly rich. These planters became the staunchest defenders of slavery, and as their wealth grew, they gained considerable political power. Another member of the planter elite was Edward Lloyd V, who came from an established family of Talbot County, Maryland. Lloyd inherited his position rather than rising to it through his own labors. His hundreds of slaves formed a crucial part of his wealth. Like many of the planter elite, Lloyd’s plantation was a masterpiece of elegant architecture and gardens. One of the slaves on Lloyd’s plantation was Frederick Douglass, who escaped in 1838 and became an abolitionist leader, writer, statesman, and orator in the North. In his autobiography, Douglass described the plantation’s elaborate gardens and racehorses, but also its underfed and brutalized slave population. Lloyd provided employment opportunities to other whites in Talbot County, many of whom served as slave traders and the “slave breakers” entrusted with beating and overworking unruly slaves into submission. Like other members of the planter elite, Lloyd himself served in a variety of local and national political offices. He was governor of Maryland from 1809 to 1811, a member of the House of Representatives from 1807 to 1809, and a senator from 1819 to 1826. As a representative and a senator, Lloyd defended slavery as the foundation of the American economy.

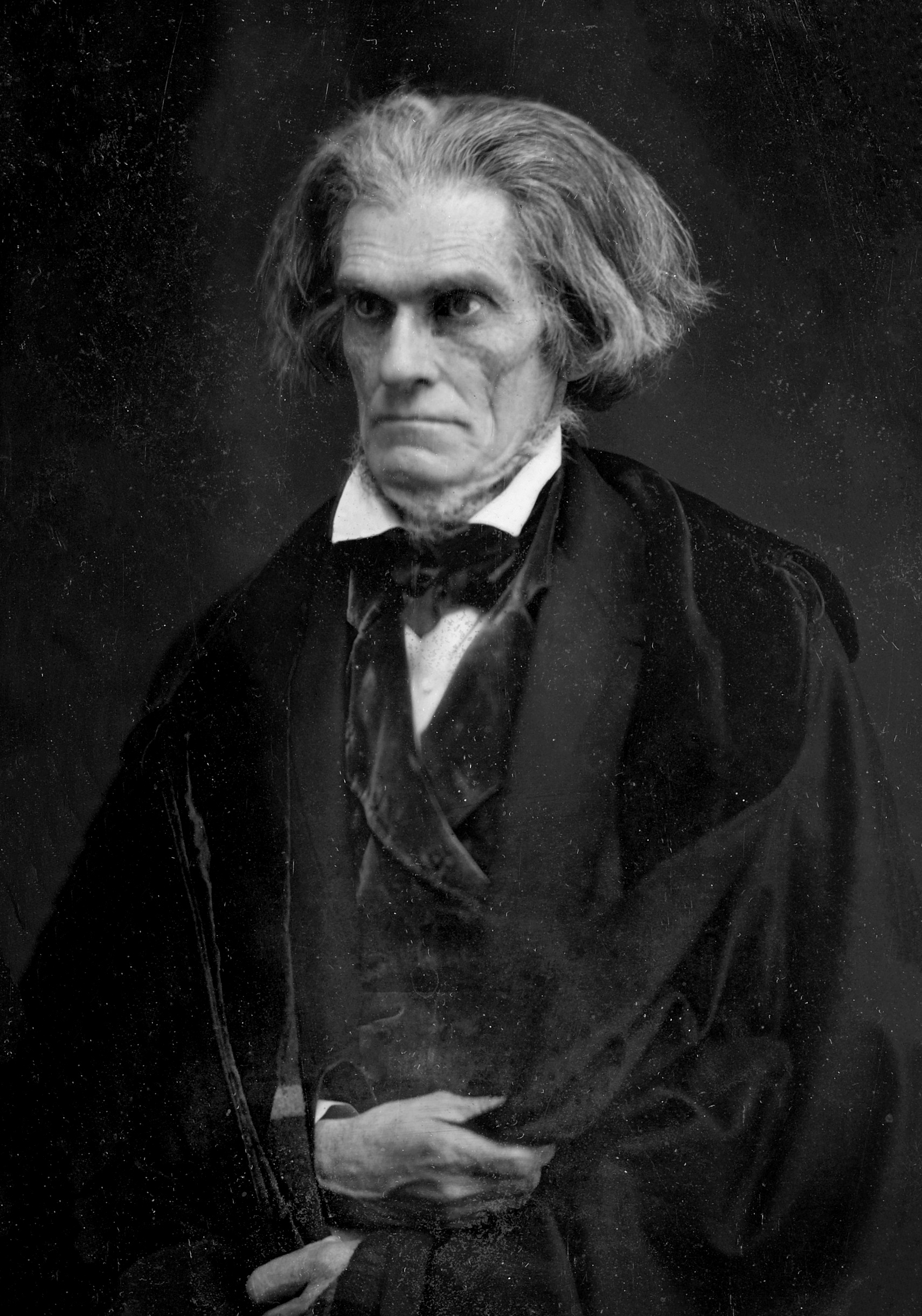

As the nation expanded in the 1830s and 1840s, the writings of abolitionists, a small but vocal group of northerners committed to ending slavery, reached a larger national audience. White southerners responded, defending slavery, their way of life, and their honor. Calhoun became a leading political theorist defending slavery and the rights of southerners he saw as an increasingly embattled minority. He argued that a majority of a separate region, although a minority of the nation, had the power to veto or disallow legislation put forward by a national hostile majority. Calhoun’s theory was reflected in his 1850 essay “Disquisition on Government” in which he defined government as a necessary means to “preserve and protect our race.” If government grew hostile to a minority society, then the minority had to take action, including forming a new government. “Disquisition on Government” advanced a profoundly anti-democratic argument, illustrating southern leaders’ intense suspicion of democratic majorities and their ability to pass laws that would challenge southern interests.

White southerners defended slavery by criticizing wage labor in the North. They argued that the Industrial Revolution had brought about a new type of “wage slavery” that they claimed was far worse than the slave labor used on southern plantations. Defenders of slaveholding also lashed out directly at abolitionists such as William Lloyd Garrison for daring to call into question their way of life. Indeed, Virginians accused Garrison of instigating Nat Turner’s 1831 rebellion. A Virginian named George Fitzhugh contributed to the defense of slavery with his 1854 book Sociology for the South, or the Failure of Free Society. Fitzhugh argued that laissez-faire capitalism benefited only the quick-witted and intelligent, leaving the ignorant at a huge disadvantage. Slaveholders, he argued, took care of the ignorant slaves of the South. Southerners provided slaves with care from birth to death, Fitzhugh asserted, in stark contrast to the wage slavery of the North where workers were at the mercy of economic forces beyond their control. Fitzhugh’s ideas exemplified southern notions of paternalism.

Garrison founded the New England Anti-Slavery Society in 1831, and the American Anti-Slavery Society (AASS) in 1833. By 1838, the AASS had 250,000 members. They rejected colonization as a racist scheme and opposed the use of violence to end slavery. Influenced by evangelical Protestantism, Garrison and other abolitionists believed in moral suasion, a technique of appealing to the conscience of the public, especially slaveholders. Moral suasion relied on dramatic narratives, often from former slaves, about the horrors of slavery, arguing that slavery destroyed families, as children were sold and taken away from their mothers and fathers. Moral suasion resonated with many women, who condemned the sexual violence against slave women and the victimization of southern white women by adulterous husbands.

Opponents made clear their resistance to Garrison and others of his ilk; Garrison nearly lost his life in 1835, when a Boston anti-abolitionist mob dragged him through the city streets. Anti-abolitionists tried to pass federal laws that made the distribution of abolitionist literature a criminal offense, fearing that such literature, with its engravings and simple language, could spark rebellious blacks to action. Their sympathizers in Congress passed a “gag rule” that forbade the consideration of the many hundreds of petitions sent to Washington by abolitionists. A mob in Illinois killed an abolitionist named Elijah Lovejoy in 1837, and the following year, ten thousand protestors destroyed the abolitionists’ newly built Pennsylvania Hall in Philadelphia, burning it to the ground.

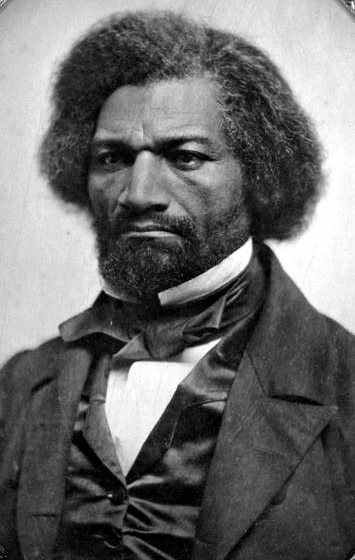

Many escaped slaves joined the abolitionist movement, including Frederick Douglass. Douglass was born in Maryland in 1818, escaping to New York in 1838. He later moved to New Bedford, Massachusetts, with his wife. Douglass’s commanding presence and powerful speaking skills electrified his listeners when he began to provide public lectures on slavery. He came to the attention of Garrison and others, who encouraged him to publish his story. In 1845, Douglass published Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, An American Slave Written by Himself, in which he told about his life of slavery in Maryland. He identified by name the whites who had brutalized him, and for that reason, along with the mere act of publishing his story, Douglass had to flee the United States to avoid being murdered. British abolitionist friends bought his freedom from his Maryland owner, and Douglass returned to the United States. He began to publish his own abolitionist newspaper, North Star, in Rochester, New York. During the 1840s and 1850s, Douglass labored to bring about the end of slavery by telling the story of his life and highlighting how slavery destroyed families, both black and white.

FREDERICK DOUGLASS ON SLAVERY

Most white slaveholders frequently raped female slaves. In this excerpt, Douglass explains the consequences for the children fathered by white masters and slave women.

Slaveholders have ordained, and by law established, that the children of slave women shall in all cases follow the condition of their mothers…this is done too obviously to administer to their own lusts, and make a gratification of their wicked desires profitable as well as pleasurable…the slaveholder, in cases not a few, sustains to his slaves the double relation of master and father…Such slaves [born of white masters] invariably suffer greater hardships…They are…a constant offence to their mistress…she is never better pleased than when she sees them under the lash,…The master is frequently compelled to sell this class of his slaves, out of deference to the feelings of his white wife; and, cruel as the deed may strike any one to be, for a man to sell his own children to human flesh-mongers,…for, unless he does this, he must not only whip them himself, but must stand by and see one white son tie up his brother, of but few shades darker…and ply the gory lash to his naked back.

—Frederick Douglass, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, An American Slave Written by Himself(1845)