2. Early English Colonies

The scarcity of additional Norse sites and the fact that we’re not all speaking Norwegian in America today remind us that the Vikings failed to sustain their settlement in Vinland. While we can probably attribute this failure partly to the resistance of the Skraelings, another decisive factor was a change in global climate. In the middle of the fourteenth century, a four hundred-year period of global cooling known as the Little Ice Age began. Scientists have measured the effects of this climate change in tree rings as far away as Patagonia. Changes in temperature and weather were noticed and recorded in Mayan and Aztec Chronicles, and also in European paintings depicting Londoners drinking, dancing, and skating on the frozen Thames (which no longer freezes). Pack ice in the North Atlantic expanded southward, making travel from Greenland to America much more difficult and dangerous. Greenland’s glaciers advanced and shortened growing seasons threatened the five hundred year-old Viking settlements there. By the early 1400s the Norse had abandoned these settlements, and without Greenland it was impossible to sustain a colony in Vinland. This 1747 map of Old Greenland mentions that the coastline where settlements had once been located had become “inaccessible” due to “floating and fixed mountains of ice.” The map even includes the location of a legendary strait that was believed to have once allowed travelers to sail through the center of the continent to North America, but had become “shut up with ice.” It’s interesting to speculate what American history would look like today, if the Vikings hadn’t been defeated by Skraelings and climate change.

Questions for Discussion

- Why is it significant that the Vikings were in the Americas five hundred years before the voyages of the Spanish and Portuguese?

- Why do historians think the remains found in Newfoundland were of a permanent settlement?

Even during the Little Ice Age, Europeans continued to venture into the icy Atlantic and many probably sailed most of the way to the new world. Basque fishing fleets, for example, began crossing the North Atlantic to visit the Grand Banks in the middle of the fifteenth century. The Banks are areas of shallow water on the edge of the North American continental shelf which are warmed by the Gulf Stream. These warm, shallow waters are an ideal home for bottom-dwelling species like Cod and Lobster. Whoever first discovered the rich fisheries of the Grand Banks off Newfoundland and Georges Bank off Cape Cod, by the late 1400s thousands of Europeans were crossing the ocean to take advantage of the bounty. Venetian explorer Giovanni Caboto (who Anglicized his name to John Cabot) reported in 1497 that Grand Banks cod were so abundant that you could almost walk across the water’s surface on their backs.

Cod had been fished in the North Atlantic at least since the period of Viking exploration, 800 to 1000 CE. The Vikings and the Basques used similar techniques, catching fish close to shore and then drying them on wooden racks assembled on nearby beaches. They probably landed regularly on the coastlines near the fishing grounds, to dry fish and to replenish their supplies of fresh water. While the locations of prime fishing grounds were closely-guarded trade secrets, by the late 1400s the Portuguese had found out and had begun sending their own fleets to the Grand Banks. Salted Cod is still an important element of Portuguese cuisine, although nowadays they get their fish from Norway.

PORTUGAL AND SPAIN

The travels of Portuguese traders to western Africa and the establishment of colonies on both the west and east coasts of the continent introduced the Portuguese to the African slave trade. Seeing slaves as a source of labor in growing the profitable crop of sugar on their Atlantic islands, the Portuguese soon began exporting African captives along with African ivory and gold. Profits from sugar fueled the Atlantic slave trade even before European discovery of the Americas, and the Portuguese islands quickly became home to sugar plantations. In time, much of the Atlantic World would become a gargantuan sugar-plantation complex in which two thirds of the Africans enslaved by Europeans worked to produce the highly profitable commodity for European consumers.

Both the Portuguese and the Spanish had been engaged in a centuries-long military campaign to regain territory in the Iberian Peninsula that had been conquered by the Muslim Umayyad Caliphate in the 8th century CE. The Reconquista ended around 1415 for the Portuguese but it took Spain the rest of the 15th century to subdue the Kingdom of Granada in what is now southern Spain. Portuguese exploration of the African Coast, discovery of a route to Asia around the southern “Horn” of Africa, and colonization of Atlantic islands in the 1400s inaugurated an era of aggressive European expansion. Columbus’s mission to find a route to Asia across the Atlantic appealed to Ferdinand and Isabella, monarchs of the newly-unified Kingdom of Spain, partly because Portugal already controlled the route around Africa. The married monarchs finally defeated Granada in 1492. They also ejected Jews and Muslims from the Kingdom who refused to convert to Christianity and used the Spanish Inquisition to prosecute “conversos” suspected of secretly practicing their original religions after converting. In the 1500s, Spain surpassed Portugal as the dominant European power. This age of exploration marked the earliest phase of globalization, in which previously isolated groups—Africans, Native Americans, and Europeans—first came into contact with each other, sometimes with disastrous results.

Question for Discussion

- Why were the Portuguese not particularly interested in Columbus’ plan to sail across the Atlantic to reach Asia?

Columbus held erroneous views that shaped his thinking about what he would encounter as he sailed west. Although ancient Greek geometers had established that the Earth was a sphere and had pretty accurately computed its size, Columbus believed the earth to be much smaller than its actual size and expected to land in Asia by traveling as far as the fishermen had in search of Cod. Although he was basically correct about the distance he would need to travel across the Atlantic, Columbus was unaware of the existence of the American continents or the Pacific Ocean. On October 12, 1492 he made landfall on an island in the Bahamas and then sailed to an island he named Hispaniola (present-day Dominican Republic and Haiti). Believing he had landed in the East Indies, Columbus called the native Taínos he found there “Indios,” giving rise to the term “Indian” for any native people of the New World. Columbus explored the islands until his flagship, the Santa Maria, ran aground on Hispaniola and had to be abandoned. The two remaining ships did not have enough room for all his men, so with the permission of a local chief Columbus left 39 sailors in a settlement he called La Navidad (because the ship had run aground on Christmas). Upon Columbus’s return to Spain in March 1493, the Spanish monarchs bestowed on him the title of Admiral of the Ocean Sea and named him governor and viceroy of the lands he had discovered.

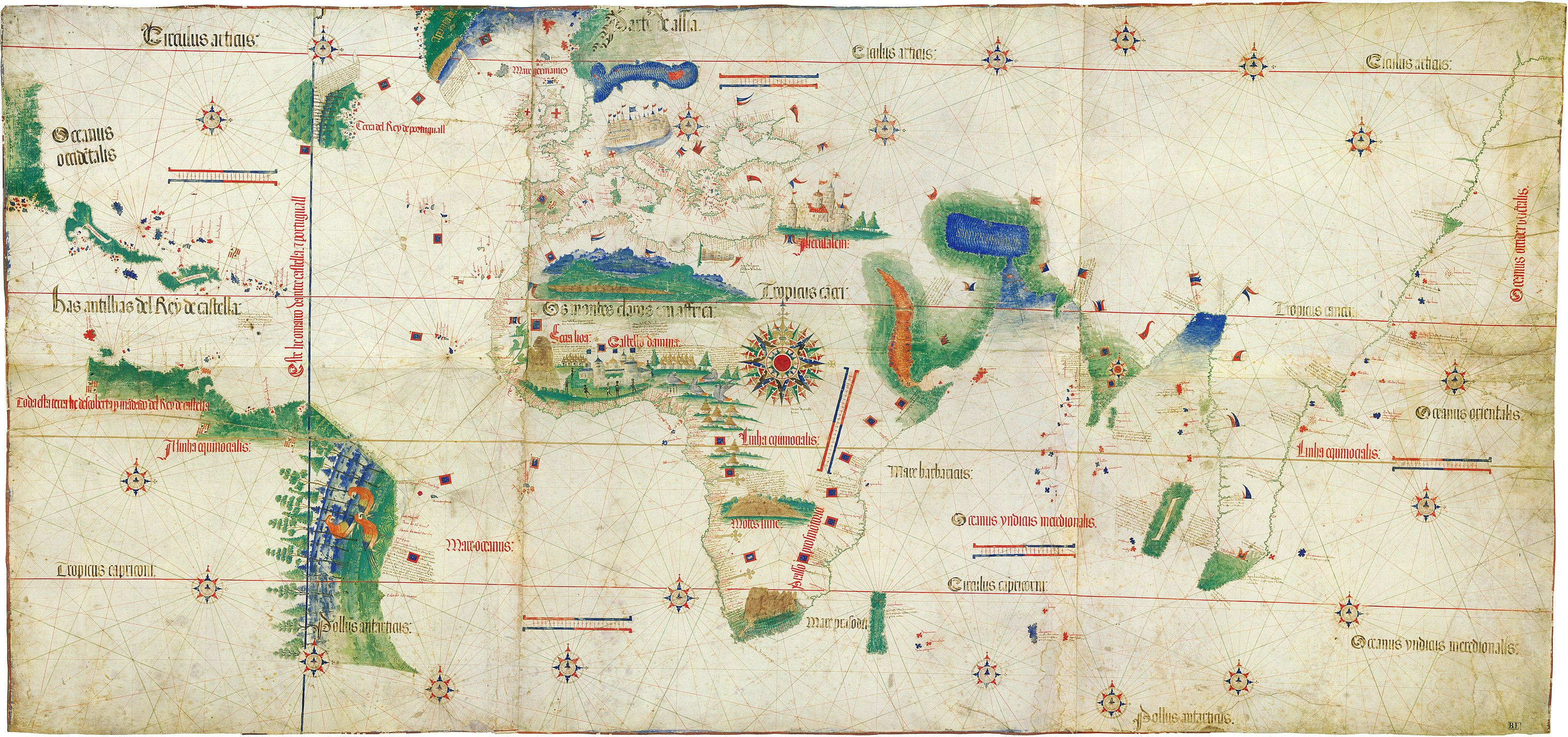

Columbus made three more voyages over the next decade, establishing Spain’s first settlement in the New World on the island of Hispaniola. Columbus made extravagant claims about the territory he had explored, including that the rivers were filled with gold. Columbus’s 1493 letter to his royal patrons, called the probanza de mérito (proof of merit), describing his “discovery” did much to inspire excitement in Europe. Another Italian navigator, Amerigo Vespucci, actually coined the term New World in a work that bore that title in Latin. Mundus Novus, written in 1503, described his voyages in a Portuguese ship which landed in the harbor that became Rio de Janeiro in Brazil. Mundus Novus was translated into several European languages and became so popular that when German cartographer Martin Waldseemüller published a map of the world in 1507, he named the two continents he added America after Vespucci. Waldseemüller’s map includes only the coastal regions of the Americas that had been explored by 1507. Europeans did not understand size of the continents or the extent of the Pacific Ocean until 1513, and Ferdinand Magellan’s mission rounded Cape Horn at the southern tip of the Americas and crossed the Pacific in 1519.

Questions for Discussion

- What impact do you think the stories told by explorers like Columbus and Vespucci had on Europeans?

- Why were the Spanish so well-prepared to become conquistadors in the “New World”?

The 1492 Columbus landfall accelerated the rivalry between Spain and Portugal, and the two powers competed for domination of European politics through the acquisition of new lands. Earlier in the 1400s, Pope Sixtus IV had granted Portugal the right to all land south of the Cape Verde islands, leading the Portuguese king to claim that the lands discovered by Columbus belonged to Portugal. Seeking to ensure that Columbus’s finds would remain Spanish, Spain’s monarchs appealed to the new pope, Spanish-born Rodrigo Borja (Pope Alexander VI), who issued two papal decrees in 1493 that gave legitimacy to Spain’s Atlantic claims at the expense of Portugal. Hoping to salvage Portugal’s Atlantic holdings, King João II began negotiations with Spain. The resulting Treaty of Tordesillas in 1494 drew a north-to-south line through South America. Spain gained territory west of the line, while Portugal retained the lands east of the line, including its African colonies and route to Asia, along with the east coast of Brazil.

THE COLUMBIAN EXCHANGE

Columbus had returned to the Caribbean in 1495 with 17 ships, 1,200 men, and according to his diaries, “seeds and cuttings for the planting of wheat, chickpeas, melons, onions, radishes, salad greens, grape vines, sugar cane, and fruit stones for the founding of orchards.” Other old-world crops that thrived in the Americas included coffee and bananas, which were brought from the Canary Islands in 1516. The Spanish and Portuguese both had extensive sugar plantations off the African coast, so it only made sense to try the plant in the tropical paradise their explorers had discovered across the Atlantic. Cattle and sheep, neither of which were native to the Americas, were delivered to Spanish conquistadors in Mexico in 1521 and by 1614, according to one of the conquistador chronicles, “the residents of Santiago [in Chile, over 4,000 miles away] possessed 39,250 head,” as well as flocks totaling 623,825 sheep. According to local traditions, when Pizarro first invaded Peru in 1524, he crossed the Andes with only eighty fighting men and forty horses, but with over 2,000 pigs. Most of the really significant Eurasian species brought to the Americas had already been introduced by the Spanish by the early 1500s, long before North American settlement began. Even species like the wild horses of the American West that would transform Plains Indian culture were escapees from the herds of the conquistadors. The Americas were home to very few large mammal species, and most could not be domesticated. Nearly all the species humans have successfully domesticated, the familiar residents of the modern farmyard, originated in Europe and Asia. These include goats, sheep, cows, horses, pigs and chickens. Eurasians began domesticating these animals between ten and fifteen thousand years ago. This was just a little too late for the Beringians to bring domesticated animals with them into North America. In any case, the Beringians were tundra hunters, not temperate-zone pastoralists. But as any good hunter would, the Beringians had brought their dogs.

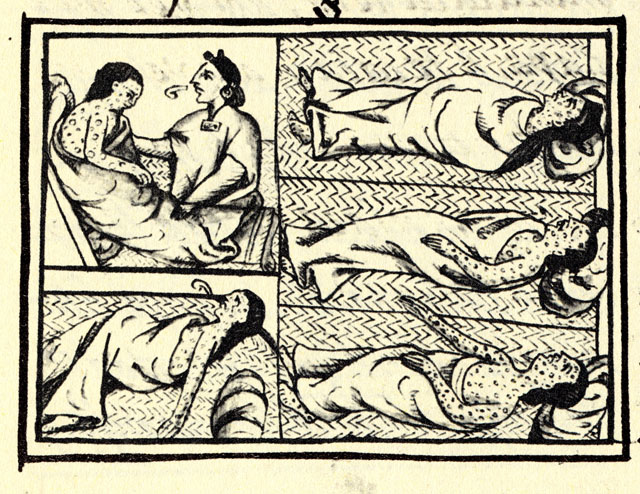

Historians call the transfer of plants and animals that began with fifteenth and early-sixteenth century European-American re-contact the Columbian exchange. The directions of these transfers and their effects on the environments and people of Europe and the Americas shaped the modern world we live in. American maize, potatoes, and cassava developed by native Americans fed growing European and Asian populations, allowing the building of new cities and industries. They remain three of the five most important staple crops in the world, even today. European animals such as pigs, sheep, chicken, and cattle thrived in the Americas, allowing both Natives and Europeans to expand and change their cultures. But the most significant change of all was the largely accidental transfer of viruses and bacteria from Europeans to Americans, which caused the deaths of possibly 90% of the native American population. Most of humanity’s major diseases originated in animals and crossed from domesticated species to their human keepers. Whooping cough and influenza came from pigs; measles and smallpox from cattle; malaria and avian flu from chickens. The people who domesticated these species and lived with the animals for generations co-evolved with them. Animal diseases became survivable when people developed antibodies and immunity. Without this inherited protection, even a routine childhood disease such as chickenpox would be devastating.

The introduction of a disease into an area without immunity is called a virgin soil epidemic. Such epidemics had happened in Eurasia, when the Romans spread smallpox into the populations they conquered, and in Europe when the expanding Mongols introduced bubonic plague. The Black Death killed probably half the population of Europe in the fourteenth century and reduced world population by over a hundred million. Virgin soil epidemics happened in the Americas when explorers and colonists introduced Eurasian diseases to native Americans who had been isolated for thousands of years. The Americans had no immunities, and even diseases that were no longer deadly to Europeans killed millions. The Eurasian diseases that attacked native populations included smallpox, measles, chickenpox, influenza, typhus, cholera, typhoid, diphtheria, bubonic plague, scarlet fever, whooping cough, and malaria.

The impact of these Eurasian diseases on Americans was one of human history’s most severe population disasters. Even the Black Death didn’t kill as large a percentage of Europeans. For example, there were probably a million people living on the Caribbean island of Hispaniola in 1492 when the Columbus left his 39 sailors in La Navidad. By 1548, there were only 500 Natives left alive. The populations of other Caribbean islands were similarly wiped out. Whole civilizations disappeared, but this was not only a tragedy for the cultures that vanished. It began a cycle of violence that became central to American history. Because once there were no natives left to work on European sugar plantations, African slaves became crucial to the survival of the West Indies economy.

The Spanish believed native peoples would work for them by right of conquest, and, in return, the Spanish would bring them Christian salvation. In theory the relationship consisted of reciprocal obligations, but in practice the Spaniards ruthlessly exploited it, seeing native people as little more than beasts of burden. Native peoples everywhere resisted both the labor obligations and the effort to change their ancient belief systems. Many retained their religion or incorporated only the parts of Catholicism that made sense to them. In addition to a system of labor grants called encomiendas, used in Spain during the Reconquista, the Spanish adapted an Inca labor system called the Mita which had required citizens of the empire to work for the public benefit. Men in Inca society between the ages of 15 and 50 worked on public projects such as road building and repair, fishing, or farming. Under the Inca, mita work was seasonal and did not prevent men from providing for their own families. Under Spanish rule, the duration of the mita expanded and work conditions worsened until the mita became synonymous with slavery. The Potosí mita, for example, drew workers from across southern Peru and Bolivia and workers often injured or maimed themselves to avoid recruitment.

Mitas and encomiendas were accompanied by a great deal of violence. One Spaniard, Bartolomé de Las Casas, denounced the brutality of Spanish rule. A Dominican friar, Las Casas had been one of the earliest Spanish settlers in the Spanish West Indies. In his early life in the Americas, Las Casas had owned Indian slaves as the recipient of an encomienda. However, after witnessing the savagery of the Spanish, he reversed his views. In 1515, Las Casas released his native slaves, gave up his encomienda, and began to advocate for humane treatment of native peoples. He lobbied for changes eventually known as the New Laws, which would eliminate slavery and the encomienda system. Ironically, Las Casas advocated the import of African slaves to reduce the exploitation of Indians. Las Casas’s exposure of the Spaniards’ horrific treatment of Indians was amplified by Spain’s Protestant adversaries and inspired the so-called Black Legend that depicted the Spanish as bloodthirsty conquerors with no regard for human life. English writers and others seized on the idea of Spain’s ruthlessness to support their own colonization projects. They demonized the Spanish and justified their own efforts as more humane. All European colonizers, however, shared a disregard for Indians. And as Indian populations disappeared as a result of the Columbian Exchange, Europeans had to look elsewhere for forced labor.

Indians were not the only source of unfree labor in the Americas; by the middle of the sixteenth century, Africans were an important component of the forced labor landscape, producing sugar and tobacco for European markets. Europeans viewed Africans as non-Christians, which they used as a justification for enslavement. At every opportunity, Africans resisted enslavement, and their resistance was met with violence. Physical, mental, and sexual violence formed a key strategy among European slaveholders in their effort to impose their will. Portuguese “factories” on the west coast of Africa, like Elmina Castle in Ghana, served as holding pens for slaves brought from Africa’s interior. The Spanish, prevented by the Treaty of Tordesillas from establishing their own slave-taking colonies on the West African coast, established a monopoly contract called the Asiento in 1518. The Dutch West India Company was awarded the monopoly in 1675 and held it until 1713, when the Asiento was passed to the British South Sea Company which held it until 1750.

Questions for Discussion

- What made the conquistadors so successful?

- Why were native societies so susceptible to Eurasian diseases?

- What were the long-term consequences of native depopulation?

CHANGES IN EUROPE

The exploits of European explorers had a profound impact both in the Americas and back in Europe. In Spain, gold and silver from the Americas helped to fuel a golden age, the Siglo de Oro, when Spanish art and literature flourished. Riches poured in from the colonies, especially from the silver mines at Potosí in the Andes and Zacatecas in Mexico. New ideas poured in from other countries and new lands.

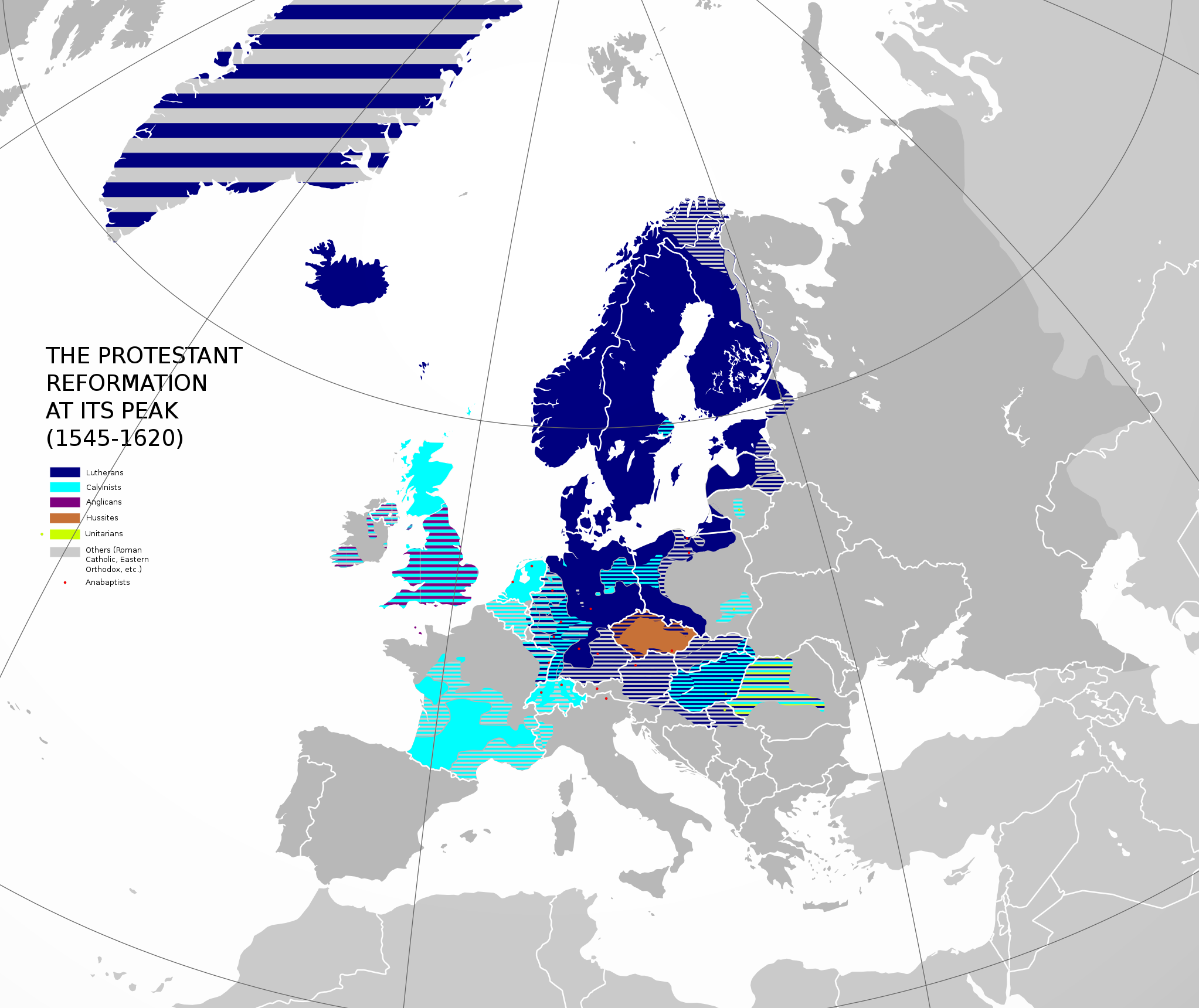

Until the 1500s, the Roman Catholic Church provided a unifying religious structure for Christian Europe. The Vatican in Rome exercised great power over the lives of Europeans, controlling not only learning and scholarship but also levying taxes on the faithful. Spain, with its New World wealth, was a bastion of the Catholic faith. Beginning with the reform efforts of Martin Luther in 1517 and John Calvin in the 1530s, however, Catholic dominance came under attack as the Protestant Reformation began. During the sixteenth century, Protestantism spread through northern Europe, and Catholic countries responded by attempting to extinguish what was seen as a heretical menace. Religious turmoil between Catholics and Protestants influenced the history of the Atlantic World as well, since different nations competed not only for control of new territories but also for the preeminence of their religious beliefs there. Just as the history of Spain’s rise to power is linked to the Reconquista, so too is the history of early globalization connected to the history of competing Christian groups in the Atlantic World.

Martin Luther was a German Catholic monk and theologian at the University of Wittenberg who took issue with the Catholic Church’s practice of selling indulgences, documents that absolved sinners in return for cash donations to finance the building of St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome. He also objected to the Catholic Church’s taxation of ordinary Germans and delivery of Mass in Latin. Although he had hoped to reform the Catholic Church while remaining a part of it, Luther’s action instead triggered a movement called the Protestant Reformation that divided the Church in two. The Catholic Church condemned him as a heretic, but a doctrine based on his reforms, called Lutheranism, spread through northern Germany and Scandinavia.

Like Luther, the French lawyer John Calvin advocated making the Bible accessible to ordinary people in their own languages. In 1535, Calvin fled Catholic France and led the Reformation movement from Geneva, Switzerland. Soon Calvin’s ideas spread to the Netherlands and Scotland. Luther’s idea that scripture should be available in the everyday language of worshippers inspired English scholar William Tyndale to translate the Bible into English in 1526. The break with the Catholic Church in England occurred in the 1530s, when Henry VIII established a new, Protestant state religion. A devout Catholic, Henry had initially opposed the Reformation. Pope Leo X even awarded him the title “Defender of the Faith.” The tides turned, however, when Henry’s Spanish Catholic wife, Catherine (the daughter of Ferdinand and Isabella), failed to produce a male heir for Henry and the king petitioned for an annulment to their marriage. The Pope refused his request and Henry created the Church of England, with himself at its head. This left him free to seize all the land and wealth of the Church, and to annul his own marriage and marry Anne Boleyn.

The new queen also failed to bear a son and when she was accused of adultery, Henry had her executed. His third wife, Jane Seymour, at long last delivered a son, Edward, who ruled for only a short time before dying in 1553 at the age of fifteen. Mary, the daughter of Henry VIII and his discarded Spanish first wife Catherine of Aragon, then came to the throne, committed to restoring Catholicism. She earned the nickname “Bloody Mary” for the many executions of Protestants that she ordered during her reign. Mary married her cousin Philip II, the King of Spain, who became King of England as well until Mary’s death in 1558. When Queen Elizabeth I took the throne, Philip proposed marriage so that he could continue as King of England. Elizabeth turned him down, which led Philip to plan an invasion of Britain, supposedly to return the nation to Catholicism. The invasion was launched in the summer of 1588, but the British navy and storms at sea defeated the Spanish Armada and established Britain as Europe’s leading naval power.

Under Elizabeth, the Church of England again became the state church, retaining the hierarchical structure and many of the rituals of the Catholic Church. However, by the late 1500s, some English members of the Church began to agitate for more reform. Known as Puritans, they worked to purify the last traces of Catholicism from the Church of England. At the time, the term “puritan” was pejorative, since many people saw Puritans as pious frauds who used religion to swindle their neighbors. Worse, many in power saw Puritans as a security threat because of their opposition to the national church. Puritans crossed the Atlantic in the 1620s and 1630s to create a New England, a haven for reformed Protestantism where Puritans could not only practice their religion freely but attain wealth and power unavailable to them in England. The conflict between Spain and England dragged on into the early seventeenth century, and Protestant nations, especially England and the newly-independent Dutch Republic, posed a significant challenge to Spain and to Catholic France as imperial rivalries played out in the Atlantic World. Spain retained its hold on Central and South America, but by the early 1600s, the nation could no longer keep England and its European rivals, the French and Dutch, from colonizing smaller islands in the Caribbean and the mainland of North America.

Question for Discussion

- How much of a factor do you think the Protestant Reformation was in the colonization of the Americas?

The French and Dutch

Spanish exploits in the New World had whetted the appetite of other would-be imperial powers, including France. In the early sixteenth century, navigator Jacques Cartier claimed northern North America for the French, naming the area New France. From 1534 to 1541, he made three voyages of discovery on the Gulf of St. Lawrence and the St. Lawrence River. Like other explorers, Cartier made exaggerated claims of mineral wealth in America, but he was unable to send great riches back to France or to establish a permanent settlement in North America. Samuel de Champlain explored the Caribbean in 1601 and then the coast of New England in 1603 before traveling farther north and founding Quebec in 1608.

Unlike other imperial powers, France fostered good relationships with native peoples, paving the way for French exploration further into the continent, around the Great Lakes, Hudson Bay, and eventually the Mississippi River. Champlain made an alliance with the Huron confederacy and the Algonquins and agreed to fight with them against their enemy, the Iroquois. The French created extensive trading networks in New France, relying on native hunters to supply furs, especially beaver pelts, in exchange for French trade goods. Beaver undercoat fur was very fine and could be felted into high quality hats that were extremely popular throughout Europe. The French also dreamed of replicating the wealth of Spain by colonizing the tropics and raising sugar. When Spanish control of the Caribbean began to weaken, the French turned their attention to small islands in the West Indies, and by 1635 they had colonized two, Guadeloupe and Martinique. Later in the seventeenth century, the French moved on larger islands including Hispaniola itself. Though it lagged far behind Spain, France’s Caribbean possessions became lucrative sugar islands that provided profits for French planters by exploiting African slave labor.

Dutch entrance into the Atlantic World is part of the story of religious and imperial conflict in the early modern era. During the sixteenth century, the provinces of the Spanish Netherlands adopted Calvinism and fought a series of wars for independence from Catholic Spain. Established in 1581, the Dutch Republic, or Holland, quickly made itself a powerful force in the race for Atlantic colonies and wealth. The Dutch relied on powerful corporations: the Dutch East India Company, chartered in 1602 to trade in Asia, and the Dutch West India Company, established in 1621 to colonize and trade in the Americas. Sailing for the Dutch East India Company in 1609, the English sea captain Henry Hudson explored New York Harbor and the river that now bears his name. Like many explorers of the time, Hudson was actually seeking a northwest passage to Asia and its wealth (Europeans remained unaware of the width of North America until the nineteenth century), but the ample furs harvested from the region he explored, especially beaver pelts, provided a reason to claim it for the Netherlands. The Dutch named their colony New Netherlands, and it served as a fur-trading outpost for the expanding Dutch West India Company. With headquarters in New Amsterdam on the island of Manhattan, the Dutch set up several regional trading posts, including one at present-day Albany. A brisk trade in furs with local Algonquian and Iroquois peoples brought the Dutch and native peoples together in a commercial network that extended throughout the Hudson River Valley and beyond.

Question for Discussion

- How did the French approach to the Americas differ from that of England?

British North America

Although England initially lacked the naval power and financial resources to challenge the Spanish and Portuguese in the Atlantic, English monarchs carefully monitored developments in the new Atlantic World and took steps to assert England’s claim to the Americas. As early as 1497, Henry VII of England had commissioned Giovanni Caboto (John Cabot), an Italian mariner, to explore new lands. Caboto sailed from England to the Grand Banks and made landfall somewhere along the North American coastline. He reported that the cod were so numerous on the Grand Banks that you could almost walk across the surface of the ocean on their backs. For the next century, English fishermen routinely crossed the Atlantic to fish the rich waters off the North American coast. However, English colonization efforts in the 1500s were closer to home, as England devoted its energy to the subjugation of Catholic Ireland. England could not consider large-scale colonization in the Americas while Spain appeared ready to invade Ireland or Scotland. Nonetheless, Queen Elizabeth commissioned English privateers, sea captains authorized to raid and harass England’s enemies. These professional pirates cruised the Caribbean, plundering Spanish ships whenever they could. Each year the English took more than £100,000 from Spain; English privateer Francis Drake first made a name for himself when, in 1573, he looted Spanish silver, gold, and pearls worth £40,000.

Elizabeth did authorize an early attempt at colonization in 1584, when Sir Walter Raleigh, a favorite of the queen’s, attempted to establish a colony at Roanoke, an island off the coast of present-day North Carolina. The colony was small, consisting of only 117 people who struggled to survive in their new home. Their governor, John White, returned to England in late 1587 to secure more people and supplies, but was unable to return to Roanoke for three years. When White’s resupply ships arrived in 1590, the entire colony had vanished. The only trace the colonists left behind was the word “Croatoan” carved into a fence surrounding the village. Governor White never discovered whether the colonists had gone to live with the Indians of the nearby island (now Hatteras) or whether some disaster had befallen them all. Roanoke is still called “the lost colony.”

In 1588, a promoter of English colonization named Thomas Hariot published A Briefe and True Report of the New Found Land of Virginia to describe the region to the English and encourage exploration and colonization. English advocates of colonization promoted its commercial advantages and promoted the establishment of Protestantism in the Americas. English merchants and aristocrats began to pool their resources to form joint stock companies, the precursor of modern corporations. The companies received charters from the crown to establish colonies, and the first permanent English settlement was established by the Virginia Company. Named for Elizabeth, the “virgin queen,” the company sent two expeditions to the New World. The northern colony, established on the Kennebec River, quickly failed. But in early 1607, 144 settlers arrived in Chesapeake Bay. Finding a river they called the James in honor of their new king, James I, they established a ramshackle settlement in a marshy region shunned by local Indians and named it Jamestown. Despite serious struggles, the colony survived.

The Jamestown settlers did not bring any workers. The colonists came from elite families: younger sons who would not inherit their fathers’ estates but had not learned any of the skills they needed to survive in a new colony. The Jamestown adventurers believed they would find instant wealth in the New World, as the Spanish had a century earlier, and did not actually expect to have to perform work. Henry Percy, the eighth son of the Earl of Northumberland, was among them. His son’s account, excerpted below, illustrates the hardships the English confronted in Virginia in 1607. The 144 men and boys who started the Jamestown colony were completely unprepared for the hardships they would face. By the end of the first winter, only 38 had not starved to death. Henry’s son George Percy, who later served twice as governor of Jamestown, kept records of the colonists’ first months in the colony which were published in London in 1608. This excerpt is from his account of August and September of 1607.

England came late to the colonization race. As Jamestown limped along in the 1610s, the Spanish Empire extended around the globe and grew rich from its global colonial project. Although they dominated Caribbean, Central, and South America, the Spanish did not completely ignore North America. In 1565, Spain established the first permanent European settlement in North America at St. Augustine in Florida. Florida would remain a Spanish territory until the early nineteenth century, which may help explain why St. Augustine is not better remembered as the first European settlement. After Jamestown’s founding, English colonization of the New World accelerated. In 1609, a ship bound for Jamestown foundered in a storm and landed on Bermuda (some believe this incident helped inspire Shakespeare’s 1611 play The Tempest). The ship’s commander, George Somers, claimed the island for the English crown. The English also began to colonize small islands in the Caribbean that had been overlooked by the Spanish American empire, such as St. Christopher (1624), Barbados (1627), Nevis (1628), Montserrat (1632), and Antigua (1632).

From the start, the English West Indies had a commercial orientation, producing the cash crops tobacco and then sugar. Very quickly, by the mid-1600s, Barbados became one of the most important English colonies because of the sugar produced there. Barbados specialized to such an extent that the colony depended on New England and the Mid-Atlantic colonies for foodstuffs because planters were unwilling to sacrifice any space on the island to grow anything but sugar. Barbados became a model for other English slave societies in the Caribbean and on the American mainland, which differed radically from England itself, where slavery was not practiced.

English Puritans also began to colonize the Americas in the 1620s and 1630s. One of the first groups of Puritans to move to North America, known as Pilgrims and led by William Bradford, had originally left England to live in the Netherlands. Fearing their children were losing their English identity among the Dutch, however, they sailed for North America in 1620 to settle at Plymouth, the first successful colony in what became known as New England. The Pilgrims differed from other Puritans in their insistence on completely separating from what they saw as the corrupt Church of England. For this reason, Pilgrims are known as Separatists.

Like Jamestown, Plymouth occupies an iconic place in American national memory. The tale of the 102 Pilgrims who crossed the Atlantic aboard the Mayflower and their struggle for survival is a well-known story of the founding of the country. The story includes the signing of the Mayflower Compact, a 1620 document some see as an expression of democratic spirit because of the cooperative nature of the agreement to live and work together. In 1630, a much larger contingent of Puritans left England to escape conformity to the Church of England and founded the Massachusetts Bay Colony in nearby Boston.

Although the Bay Colony’s leaders wrote of their goal to create a “City upon a Hill” at Boston that would be an example of pious life, leaders of the colony were also very interested in material success. John Winthrop, the Puritan leader who helped establish Boston and who was Governor of the Massachusetts Bay Colony four times before 1650, sent his second son Henry to help establish Barbados in 1626. When Oliver Cromwell’s Civil War halted the flow of commercial shipping between England and the ten-year-old Bay Colony in 1640, trade with the West Indies saved Boston’s economy. Governor Winthrop’s younger son Samuel joined the growing community of New England merchants in the Caribbean sugar islands in 1647.

Questions for Discussion

- Why were the settlers of Jamestown unwilling in working to make their colony successful?

- What was the most important early English colony, from a financial perspective?

When they chose to settle along Chesapeake Bay, the English unknowingly placed themselves at the center of the Powhatan Confederacy, a powerful Algonquian alliance of thirty native groups with perhaps as many as twenty-two thousand people. Tensions ran high between the English and the Powhatan, and near-constant war prevailed as more and more English settlers arrived. The First Anglo-Powhatan War (1609–1614) resulted not only from the English colonists’ intrusion onto Powhatan land, but also from their refusal to follow native social protocols of gift exchange. English actions infuriated and insulted the Powhatan. In 1613, the settlers captured Pocahontas (also called Matoaka), the daughter of Wahunsenacawh, who the English called Chief Powhatan. Pocahontas helped quell the war in 1614 and promoters of colonization publicized her story as an example of the good work of converting the Powhatan to Christianity. Pocahontas married John Rolfe and travelled with him to England, where she met King James I. She died in London of a European disease, leaving behind a two-year old son, Thomas Rolfe, who returned to Virginia.

Peace in Virginia did not last long. The Second Anglo-Powhatan War (1620s) broke out after the death of Wahunsenacawh because of the expansion of the English settlement nearly one hundred miles into the interior and because of the continued insults and friction caused by English activities. The Chief’s brother, Opechanacanough, had never been reconciled to the English presence and went to war as soon as he became chief. The Powhatan attacked in 1622 and succeeded in killing almost 350 English, about a third of the settlers. The English responded by annihilating every Powhatan village around Jamestown and from then on became even more intolerant. The Third Anglo-Powhatan War (1644–1646) began with a surprise attack in which the Powhatan killed around five hundred English colonists. However, their ultimate defeat in this conflict forced the Powhatan to acknowledge King Charles I as their sovereign. Opechancanough was captured and paraded through Jamestown as a prisoner, although he was over 90 years old. The chief was then shot in the back by a soldier who had been assigned to guard him. The Anglo-Powhatan Wars, spanning nearly forty years, illustrate the degree of native resistance that resulted from English intrusion into the Powhatan confederacy.