8. A New Republic

Hereditary Monarchy rests on the idea that instead of all people having equal natural rights, a particular person has many more rights than everybody else, perhaps through some type of divine selection. Kingship is also based on dynastic succession, in which the monarch’s child or other relative inherits the throne. Despite claims of divine selection, dynastic contests produced chronic conflict and warfare in Europe. In the eighteenth century, well-established monarchs ruled most of Europe and, according to tradition (especially in constitutional monarchies) were obligated to protect and guide their subjects. However, by the mid-1770s, many American colonists believed that George III, the king of Great Britain, had failed to do so. Patriots believed the British monarchy under George III had been corrupted and the king had become a tyrant who cared nothing for the traditional liberties afforded to members of the British Empire. The disaffection from monarchy explains why a republic appeared a better alternative to the revolutionaries.

American revolutionaries looked to the past for inspiration for their break with the British monarchy and their adoption of a republican form of government. The Roman Republic provided guidance. Much like the Americans in their struggle against Britain, Romans had thrown off monarchy and created a republic in which Roman citizens would appoint or select the leaders who would represent them. The fact that the Roman Republic was ultimately replaced by the Roman Empire did not dissuade the Patriots, who believed they could prevent the types of changes that had led Rome into imperialism.

While republicanism offered an alternative to monarchy, it was also an alternative to democracy, a system of government characterized by majority rule, where the majority of citizens have the power to make decisions binding upon the whole. To many revolutionaries, especially wealthy landowners, merchants, and planters, democracy did not offer a good replacement for monarchy. Indeed, conservative Whigs opposed democracy, which they equated with anarchy. In the tenth in a series of essays later known as The Federalist Papers, Virginia plantation-owner James Madison wrote: “Democracies have ever been spectacles of turbulence and contention; have ever been found incompatible with personal security or the rights of property; and have in general been as short in their lives as they have been violent in their deaths.” Many shared this perspective and worked hard to keep democratic tendencies in check. It is easy to understand why democracy seemed threatening: majority rule can easily overpower minority rights, and the wealthy few had reason to fear that a hostile and envious majority could seize and redistribute their wealth.

While many now assume the United States was founded as a democracy, conservative Whigs believed in government by a patrician class composed of a small number of privileged families. Radical Whigs favored broadening the popular participation in political life and pushed for a bit more democracy. No one, however, wanted to include women, Africans, or Indians in the political class of the new nation. The great debate, after independence was won, centered on the question, who should rule in the new American republic?

According to the Patriots’ political theory, a republic requires its citizens to cultivate virtuous behavior; if the people were virtuous, the republic would survive. If the people became corrupt, the republic would fall. Whether republicanism succeeded or failed in the United States would depend on civic virtue and an educated citizenry. Revolutionary leaders agreed that the ownership of property provided one way to measure an individual’s virtue, arguing that property holders had the greatest stake in society and therefore could be trusted to make decisions for it. By the same token, non-property holders, they believed, should have very little to do with government. Unlike a democracy, in which the mass of non-property holders could exercise the political right to vote, a republic would limit political rights to property holders. In this way, republicanism exhibited a bias toward the elite, a preference that is understandable given the colonial legacy. During colonial times, wealthy planters and merchants in the American colonies had looked to the British ruling class, whose social order demanded deference from those of lower rank, as a model of behavior. Old habits of social hierarchy died hard, even in a revolutionary society that had proclaimed “all men are created equal”.

BENJAMIN FRANKLIN’S THIRTEEN VIRTUES FOR CHARACTER DEVELOPMENT

In the 1780s, Benjamin Franklin carefully defined thirteen virtues to help guide his countrymen in maintaining a virtuous republic. His choice of thirteen is telling since he wrote for the citizens of the thirteen new American republics. These virtues were:

- Temperance. Eat not to dullness; drink not to elevation.

2. Silence. Speak not but what may benefit others or yourself; avoid trifling conversation.

3. Order. Let all your things have their places; let each part of your business have its time.

4. Resolution. Resolve to perform what you ought; perform without fail what you resolve.

5. Frugality. Make no expense but to do good to others or yourself; i.e., waste nothing.

6. Industry. Lose no time; be always employ’d in something useful; cut off all unnecessary actions.

7. Sincerity. Use no hurtful deceit; think innocently and justly, and, if you speak, speak accordingly.

8. Justice. Wrong none by doing injuries, or omitting the benefits that are your duty.

9. Moderation. Avoid extremes; forbear resenting injuries so much as you think they deserve.

10. Cleanliness. Tolerate no uncleanliness in body, cloaths, or habitation.

11. Tranquillity. Be not disturbed at trifles, or at accidents common or unavoidable.

12. Chastity. Rarely use venery but for health or offspring, never to dullness, weakness, or the injury of your own or another’s peace or reputation.

13. Humility. Imitate Jesus and Socrates.

George Washington served as a role model par excellence for the new republic, embodying the exceptional talent and public virtue prized under the political and social philosophy of republicanism. He did not seek to become the new king of America, but retired as commander in chief of the Continental Army and returned to his Virginia estate at Mount Vernon to resume his life among the planter elite. Washington modeled his behavior on the Roman aristocrat Cincinnatus, a representative of the patrician or ruling class, who had also retired from public service in the Roman Republic and returned to his estate to pursue agricultural life. Like Cincinnatus, Washington was not giving up much by retiring. He was one of the wealthiest men in America and his estates covered over 50,000 acres of Virginia’s best farmland.

The aristocratic side of republicanism and the belief that the true custodians of public virtue were those who had commanded in the military found expression in the Society of the Cincinnati, of which Washington was the first president general. Founded in 1783, the society admitted only officers of the Continental Army and the French forces, not militia members or minutemen. Following the rule of primogeniture, the eldest sons of members inherited their fathers’ memberships. The society still exists today and retains the motto Omnia relinquit servare rempublicam (“He relinquished everything to save the Republic”).

In eighteenth-century America, as in Great Britain, the legal status of married women was defined as coverture, meaning a married woman (or feme covert) had no legal or economic status independent of her husband. She could not conduct business or buy and sell property. Her husband controlled any property she brought to the marriage, although he could not sell it without her agreement. Married women’s status as femes covert did not change as a result of the Revolution, and wives remained economically dependent on their husbands. The women of the newly independent nation did not call for the right to vote, but some wives of elite republican statesmen, began to agitate for equality under the law between husbands and wives, and for the same educational opportunities as men. Some women hoped to overturn coverture. Abigail Adams wrote to her husband, Whig leader John Adams in 1776, “In the new code of laws which I suppose it will be necessary for you to make, I desire you would remember the ladies and be more generous and favorable to them than your ancestor. Do not put such unlimited power in the husbands. Remember, all men would be tyrants if they could.”

Mainstream culture believed the home was a separate domestic sphere assigned to women who were expected to practice republican virtues, especially frugality and simplicity. Republican motherhood meant that women, more than men, were responsible for raising good children and instilling in them all the virtue necessary to ensure the survival of the republic. Benjamin Rush, a Whig educator and physician from Philadelphia, strongly advocated for the education of girls and young women as part of the larger effort to ensure that republican virtue and republican motherhood would endure.

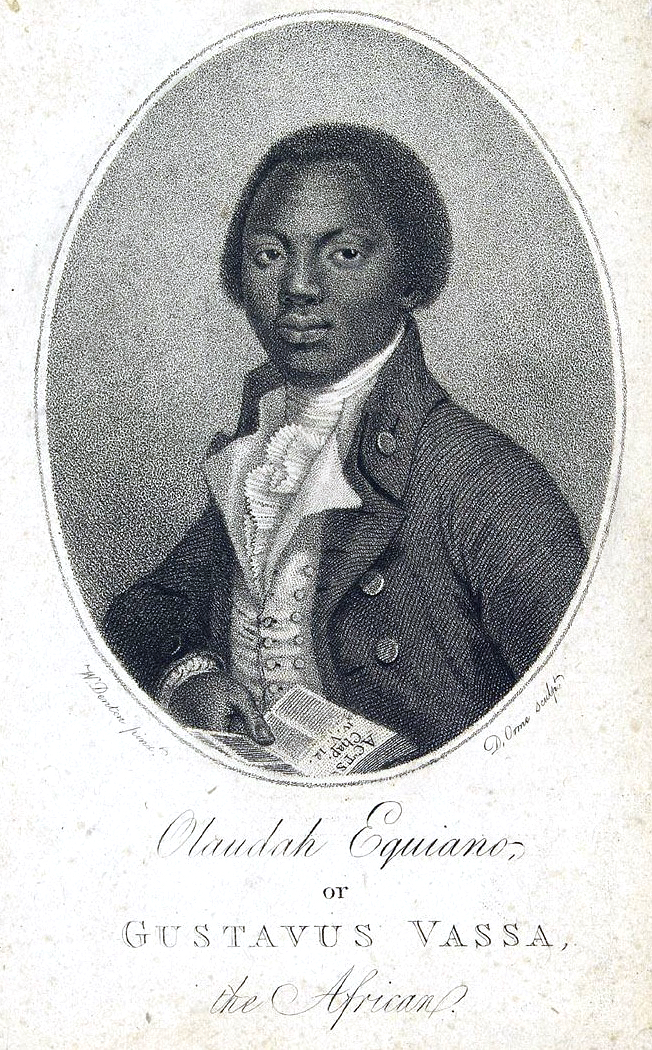

By the time of the Revolution, slavery had been firmly in place in America for well over a century. The Revolution reinforced assumptions about race among white Americans, who viewed the new nation as a white republic; blacks were slaves, and Indians had no place. Racial hatred of blacks increased during the Revolution because many slaves fled their white masters for the freedom offered by the British through Dunmore’s Proclamation. The same resentment applied to Indians who had allied themselves with the British. Benjamin Franklin wrote in the 1780s that alcoholism would soon wipe out the Indians, leaving the land free for white settlers. Slavery was the most glaring contradiction between the ideal of equality stated in the Declaration of Independence and the reality of race relations in the late eighteenth century. Racism shaped white views of blacks. Although he penned the Declaration of Independence, Thomas Jefferson owned more than one hundred slaves and he freed only a few either during his lifetime or in his will. White slaveholders took their female slaves as mistresses, as most historians agree (and DNA evidence has recently proven) that Jefferson did with one of his slaves, Sally Hemings. They had several children, who were apparently the only slaves Jefferson ever freed in his lifetime or in his will.

Jefferson understood the contradiction fully, and his writings reveal hard-edged racist assumptions. In his Notes on the State of Virginia in the 1780s, Jefferson urged the end of slavery in Virginia and the removal of blacks from that state. He wrote: “It will probably be asked, Why not retain and incorporate the blacks into the state, and thus save the expense of supplying, by importation of white settlers, the vacancies they will leave? Deep rooted prejudices entertained by the whites; ten thousand recollections, by the blacks, of the injuries they have sustained; new provocations; the real distinctions which nature has made; and many other circumstances, will divide us into parties, and produce convulsions which will probably never end but in the extermination of the one or the other race. —To these objections, which are political, may be added others, which are physical and moral.” Jefferson envisioned an “empire of liberty” for white farmers and relied on the argument of sending blacks out of the United States, even if doing so would completely destroy the slaveholders’ wealth in their human property. Southern planters strongly objected to Jefferson’s views on abolishing slavery and removing blacks from America. When Jefferson was a candidate for president in 1796, an anonymous “Southern Planter” wrote, “If this wild project succeeds, under the auspices of Thomas Jefferson, President of the United States, and three hundred thousand slaves are set free in Virginia, farewell to the safety, prosperity, the importance, perhaps the very existence of the Southern States”. Slaveholders and many other Americans protected and defended the institution.

While slavery existed in all the colonies that had become new states, the ideals of the Revolution generated a movement toward the abolition of slavery. Private manumissions, in which slaveholders freed their slaves, provided one pathway from bondage. Slaveholders in Virginia freed about ten thousand slaves. Other revolutionaries formed societies dedicated to abolishing slavery. Dr. Benjamin Rush and other Philadelphia Quakers formed what became the Pennsylvania Abolition Society in 1775. New Yorkers formed the New York Manumission Society in 1785, to educate black children and protect free blacks from kidnapping. Slavery persisted in the North, however, and the situation in Massachusetts highlights the complexity of the situation. The state’s 1780 constitution technically freed all slaves, but several hundred individuals remained enslaved in the state until a series of court decisions undermined slavery in Massachusetts. Several slaves, citing assault by their masters, successfully sought their freedom in court. Despite these legal victories, about eleven hundred slaves continued to be held in the New England states in 1800. Over thirty-six thousand slaves remained in the North, with the highest concentrations in New Jersey and New York. New York only gradually phased out slavery, with the last slaves emancipated in the late 1820s.

The 1783 Treaty of Paris did not address Indians at all. All the lands held by the British east of the Mississippi and south of the Great Lakes (except Spanish Florida) were handed over to the new American republic. Though the treaty remained silent on the issue, much of the territory now included in the boundaries of the United States had only been claimed by the British and remained firmly under the control of native peoples. Earlier in the eighteenth century, a “middle ground” had existed between powerful native groups in the West and British and French imperial zones, where the various groups interacted and accommodated each other. As had happened in the French and Indian War and Pontiac’s Rebellion, the Revolutionary War turned the middle ground into a battle zone that no one group controlled. During the Revolution, many Indians had remained neutral. Some native groups, such as the Delaware and the Iroquois Confederacy, split into factions. The Mohawk, Cayuga, Onondaga, and Seneca fought on the British side, while the Oneida and Tuscarora supported the revolutionaries. Ohio River Valley tribes such as the Shawnee, Miami, and Mungo that had been fighting for years against colonial expansion west also supported the British. Some native peoples who had previously allied with the French hoped the conflict between the colonies and Great Britain might lead to French intervention and the return of French rule. Few Indians sided with the American revolutionaries because almost all revolutionaries in the middle ground viewed them as an enemy to be destroyed. This racial hatred toward native peoples found expression in the American massacre of ninety-six Christian Delawares in 1782. Most of the dead were women and children. After the war, the victorious Americans turned a deaf ear to Indian claims to their ancestral lands and moved aggressively to assert control over western New York and Pennsylvania. In response, Mohawk leader Joseph Brant formed the Western Confederacy, an alliance of native peoples who pledged to resist American intrusion into what was then called the Northwest. The Northwest Indian War (1785–1795) ended with the defeat of the Indians and their claims. Under the Treaty of Greenville (1795), the United States gained dominion over land in Ohio.

After the Revolution, several colonies with official, tax-supported churches questioned the validity of state-authorized religion, limitation of public office-holding to those of a particular denomination, and payment of mandatory taxes to support churches. In Virginia, the established colonial religion had been the Church of England, which did not tolerate Catholics, Baptists, or followers or other faiths. In 1786 Virginia’s lawmakers approved the Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom, which ended the Church of England’s privileged status and allowed religious liberty. Under the statute, no one could be forced to attend or support a specific church or be prosecuted for his or her beliefs. Pennsylvania’s original constitution limited officeholders in the state legislature to those who professed a belief in both the Old and the New Testaments, which prohibited Jews from holding office. In 1790 Pennsylvania removed this qualification from its constitution. The New England states were slower to embrace freedom of religion. In the former Puritan colonies, the Congregational Church remained the church of most inhabitants. Massachusetts, Connecticut, and New Hampshire all required the public support of Christian churches. The Massachusetts constitution blended the goal of republicanism with the goal of promoting Protestant Christianity, stating “As the happiness of a people, and the good order and preservation of civil government, essentially depend upon piety, religion and morality; and [that] these cannot be generally diffused through a community, but by the institution of the public worship of GOD, and of public instructions in piety, religion and morality”. Massachusetts did not disestablish the Congregational Church and make its support voluntary rather than a legal requirement until January 1, 1834.

Read more about religion and state governments at the Religion and the Founding of the American Republic exhibition page on the Library of Congress site.

In 1776, Whig leader John Adams urged the thirteen rebellious colonies to write their own state constitutions. Enlightenment political thought profoundly influenced Adams and other revolutionary leaders seeking to create viable republican governments. The ideas of the French philosopher Montesquieu, who had advocated the separation of powers in government, guided Adams’s thinking. Responding to a request for advice on proper government from North Carolina, Adams wrote Thoughts on Government, which influenced many state legislatures. Adams did not advocate democracy, he wrote “there is no good government but what is republican.” Fearing the potential for tyranny with only one group in power, he suggested a system of checks and balances in which three separate branches of government—executive, legislative, and judicial—would maintain a balance of power. He also proposed that each state remain sovereign, as its own republic. The state constitutions of the new United States illustrate different approaches to addressing the question of how much democracy would prevail in the thirteen republics. Some states embraced democratic practices, while others adopted far more aristocratic and republican ones.

The 1776 Pennsylvania constitution and the 1784 New Hampshire constitution both provide examples of democratic tendencies. In Pennsylvania, the requirement to own property in order to vote was eliminated, which opened voting to most free white male citizens of Pennsylvania. The 1784 New Hampshire constitution allowed every small town and village to send representatives to the state government, making the lower house of the legislature a model of democratic government. Conservative Whig John Adams reacted with horror to the 1776 Pennsylvania constitution, declaring that it was “so democratical that it must produce confusion and every evil work.” Pennsylvania’s constitution also eliminated the executive branch (there was no governor) and the upper house. Instead, Pennsylvania had a one-house, unicameral legislature. The Maryland and South Carolina constitutions provide examples of efforts to limit the power of a democratic majority. Maryland’s, written in 1776, restricted office holding to the wealthy planter class. A man had to own at least £5,000 worth of personal property to be the governor of Maryland and £1,000 to be a state senator. This excluded over 90 percent of the white males in Maryland from political office. The 1778 South Carolina constitution also protected the interests of the wealthy. Governors and lieutenant governors of the state had to have “a settled plantation or freehold…of the value of at least ten thousand pounds currency, clear of debt.” South Carolina state senators had to own estates valued at £2,000.

John Adams wrote most of the 1780 Massachusetts constitution, and it reflected his fear of too much democracy. Adams created two legislative chambers, an upper and lower house, and a strong governor with broad veto powers. In addition to allowing only wealthy men to hold office, Adams limited voting to men worth at least sixty pounds. To further check democracy, judges were appointed, not elected and the state capitol was set in the commercial center of Boston, which made it difficult for farmers from the western part of the state to attend legislative sessions.

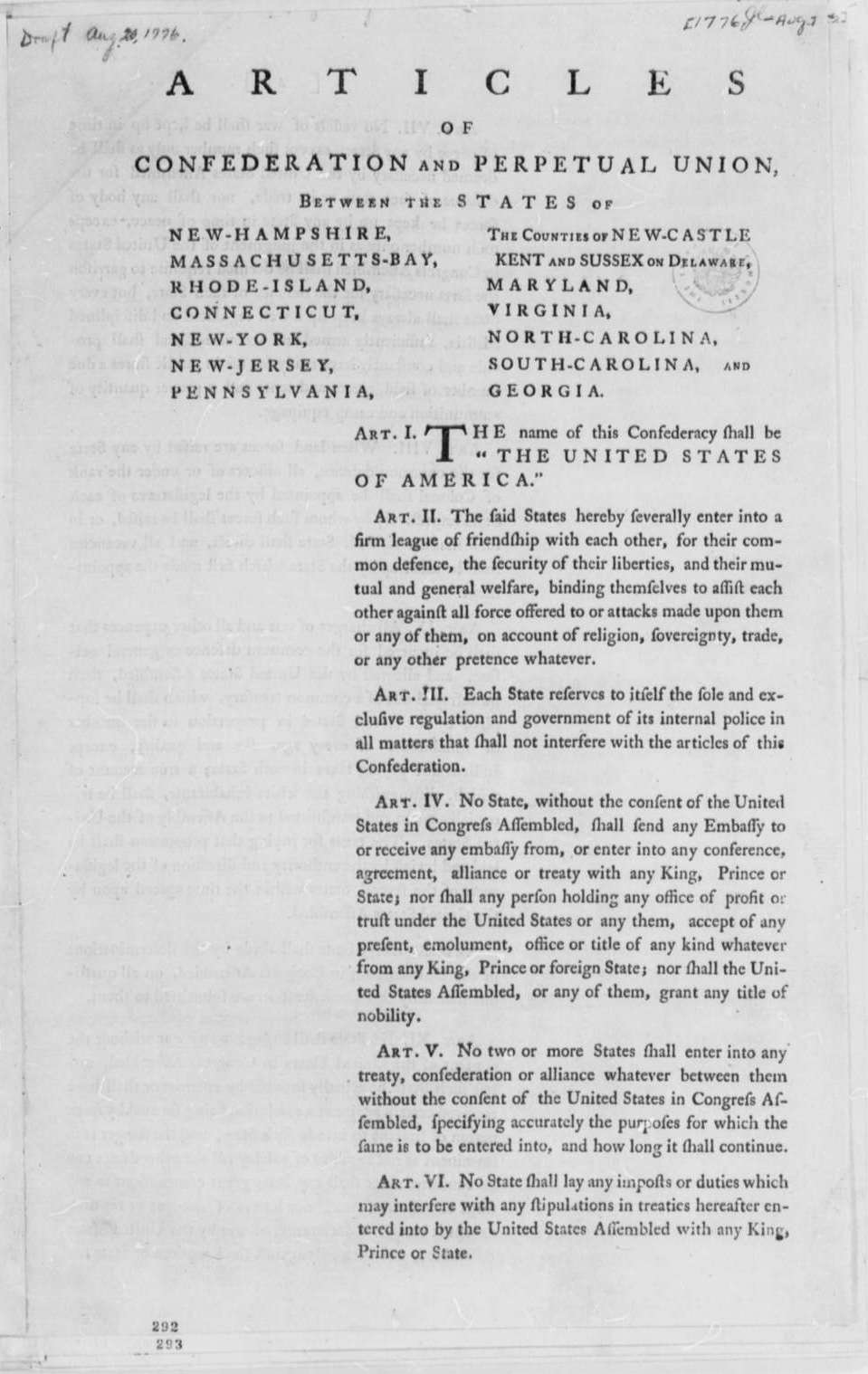

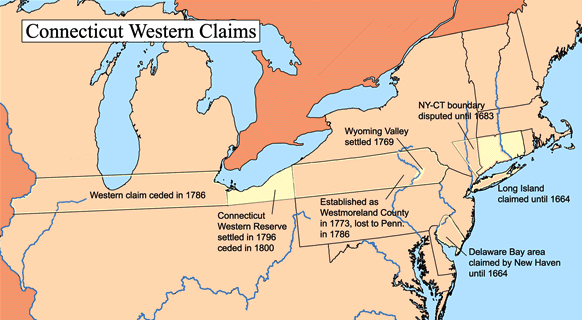

Most revolutionaries pledged their greatest loyalty to their individual states; they feared a strong national government and took some time to adopt the Articles of Confederation as the first national constitution. Reaching agreement on the Articles of Confederation proved difficult as members of the Continental Congress argued over western land claims. Connecticut, for example, used its colonial charter to assert its claim to western lands in Pennsylvania and the Ohio Territory. Members of the Continental Congress also debated what type of representation would be best and tried to figure out how to pay the expenses of the new nation they hoped to establish. In lieu of creating a federal government, the Articles of Confederation created a “league of friendship” between the states. Congress readied the Articles in 1777 but did not officially approve them until 1781. The delay of four years illustrates the difficulty of getting the thirteen new states to agree.

The Articles of Confederation authorized a unicameral legislature, a continuation of the earlier Continental Congress. The people would not vote directly for members of the national Congress; state legislatures would decide who would represent the state. In practice, the national Congress was composed of state delegations. There was no president or executive office of any kind, and there was no national judiciary (or Supreme Court) for the United States. Passing a law under the Articles of Confederation proved difficult. It took the consensus of nine states for any measure to pass and amending the Articles required the consent of all the states, also extremely difficult to achieve. And any acts passed by the Congress were non-binding; states had the option to enforce them or not. While the Congress theoretically had power over Indian affairs and foreign policy, individual states could choose whether or not to comply.

Congress did not have the power to tax citizens of the United States, a fact that had serious consequences for the republic. During the Revolutionary War the Continental Congress had sent requisitions for funds to the individual states, which already had an enormous financial burden paying for militias and supplying them. The states failed to provide even half the funding requested by the Congress during the war, which led to a national debt in the tens of millions by 1784. Some members of the Congress argued that the national government needed the power to tax. This required amending the Articles of Confederation with the consent of all the states. “Nationalists” who called for a stronger federal government proposed a 5 percent tariff on imports which would have yielded enough revenue to clear the debt. However, Rhode Island vetoed their proposal. Plans for a national bank also failed to win unanimous support. Without revenue, the Congress could not pay back American creditors who had lent it money. However, fearing that defaults would destroy the republic’s credit and leave it unable to secure loans, Congress did manage to make interest payments to foreign creditors in France and the Dutch Republic. Establishing workable foreign and commercial policies under the Articles of Confederation also proved difficult. Each state could decide for itself whether to comply with treaties between the Congress and foreign countries. Both Great Britain and Spain understood the weakness of the Confederation Congress and refused to make commercial agreements with the United States because they doubted they would be enforced. British goods flooded U.S. markets in the 1780s, in a repetition of the economic imbalance that existed before the Revolutionary War.

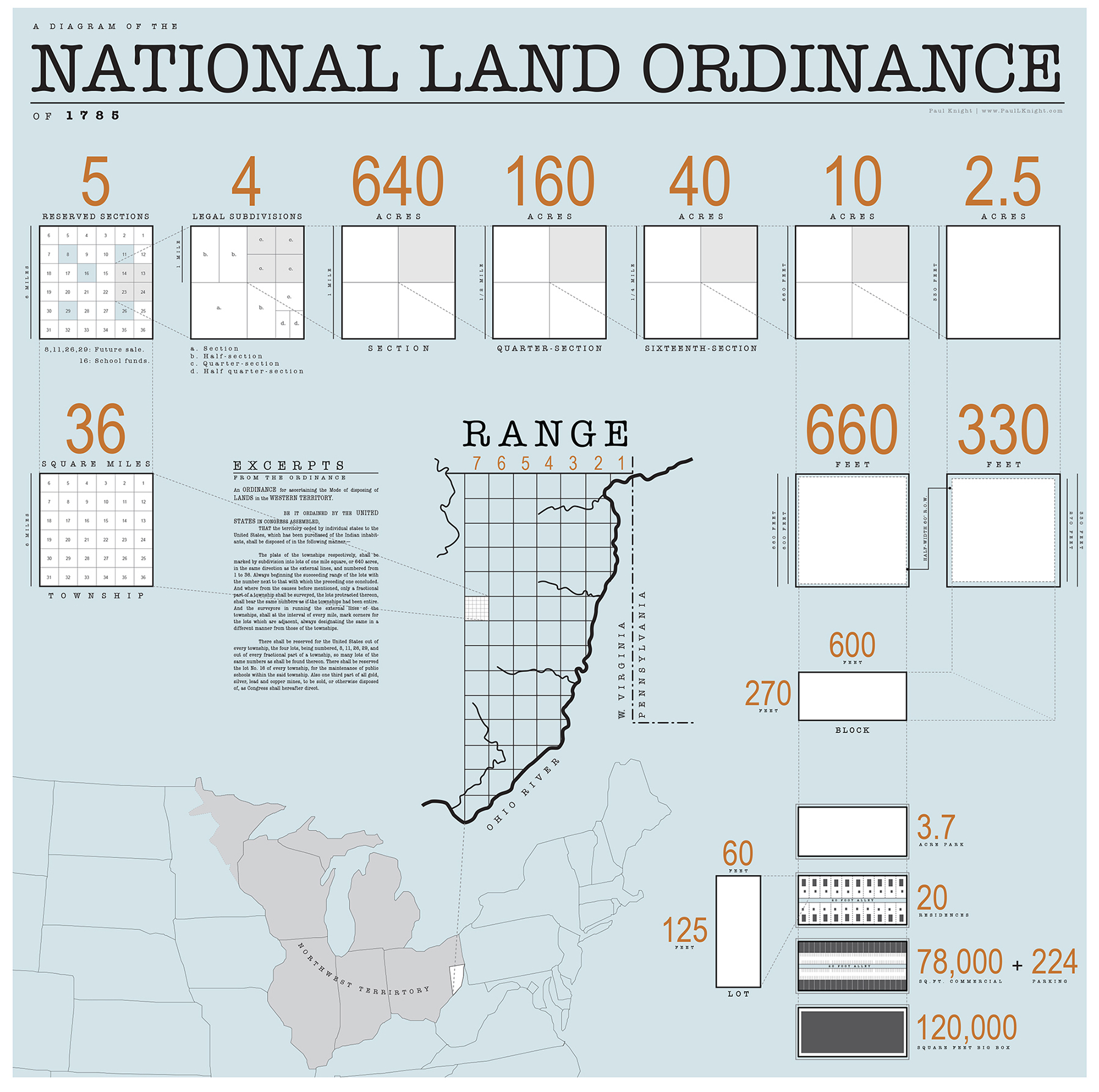

The Confederation Congress was successful in passing a series of land ordinances that established rules for the settlement of western lands in the public domain and the admission of new states to the republic. Congress created the Mississippi and Southwest Territories and stipulated that slavery would be permitted there. The Ordinance of 1784, written by Thomas Jefferson and the first of the Northwest Ordinances, directed that new states would be formed from a huge area of land below the Great Lakes, and these new states would have equal standing with the original states. The Ordinance of 1785 called for the division of this land into rectangular plots in order to prepare for the government sale of land. Surveyors would divide the land into six-mile square townships that would be subdivided into thirty-six one square-mile plots of 640 acres each. The price of an acre of land was set at a minimum of one dollar, and the land was to be sold at public auction under the direction of the Confederation. The Ordinance of 1787 officially turned the land into an incorporated territory called the Northwest Territory and prohibited slavery north of the Ohio River. The map of the 1787 Northwest Territory shows how the public domain was to be divided by the national government for sale. Townships of thirty-six square miles were to be surveyed. Each had land set aside for schools and other civic purposes. Smaller parcels could then be made: a 640-acre section could be divided into quarter-sections of 160 acres, and then again into sixteen sections of 40 acres. The geometric grid pattern established by the ordinance is still evident today on the American landscape and much of the Midwest, when viewed from an airplane, is composed of an orderly grid system. Congress would appoint a governor for the territories, and when the population in the territory reached five thousand free adult settlers, those citizens could create their own legislature and begin the process of moving toward statehood. When the population reached sixty thousand, the territory could become a new state. And there would be no slavery allowed in the Northwest territory, which encouraged the growth of family farms rather than large plantations.

Despite Congress’s victory in creating an orderly process for organizing new states and territories, land sales failed to produce enough revenue to fix the dire economic problems facing the new country in the 1780s. Each state had issued large amounts of paper money and in the aftermath of the Revolution, inflation of state paper money and the Continental dollar made the currency militias had been paid in virtually worthless. Added to this dilemma was America’s lack of specie (gold and silver currency) to conduct routine business. Meanwhile, demobilized soldiers, many of whom had spent the years of their youths fighting rather than learning a peacetime trade, searched desperately for work. The economic crisis came to a head in 1786 and 1787 in western Massachusetts, where farmers faced high state taxes and debts they found nearly impossible to pay with the worthless state and Continental paper money. For several years after the war’s end, these indebted citizens had petitioned the state legislature for aid. Many were veterans of the Revolution who had returned to farms and families after the fighting ended and now faced losing their homes. Their petitions to the Massachusetts legislature highlighted economic and political issues: how could people pay their debts and state taxes when paper money proved unstable? Why was the state government located in Boston, the center of the merchant elite? Why did John Adams’s 1780 Massachusetts constitution cater to the interests of the wealthy? To the indebted farmers, the situation in the 1780s seemed hauntingly familiar; the revolutionaries had routed the British, but a new form of seemingly corrupt and self-serving government had replaced the overseas tyranny.

In 1786, when the state legislature again refused to address the petitioners’ requests, Massachusetts citizens took up arms and closed courthouses across the state to prevent foreclosures (seizure of land to cover overdue loan payments) on farms in debt. The farmers wanted their debts forgiven and they demanded that the 1780 constitution be revised to address the needs of citizens beyond the wealthy elite who qualified to vote and serve in the legislature. Many of the rebels were veterans of the war for independence, including Captain Daniel Shays from the hill-town of Pelham in western Massachusetts. Although Shays was only one of many former officers in the Continental Army who took part in the revolt, authorities in Boston singled him out as a ringleader, and the uprising became known as Shays’s Rebellion. The Massachusetts legislature responded to the closing of the courthouses by Shays and other “regulators” with a flurry of legislation designed to punish the rebels. The government offered the rebels clemency if they surrendered and took an oath of allegiance. Otherwise, local officials were empowered to use deadly force against them without fear of prosecution. Rebels would lose their property, and if any militiamen refused to defend the state, they would be executed. Despite Boston’s threats, the rebellion continued. Governor James Bowdoin raised a private army of forty-four hundred men, funded by wealthy Boston merchants, without the approval of the legislature. In January 1787 the rebels attempted to seize the federal armory in Springfield, Massachusetts. A force loyal to the state defeated them there, although the rebellion continued into February. Shays’ Rebellion resulted in eighteen deaths, but the uprising had lasting effects. To men of property and conservative Whigs, Shays’ Rebellion suggested the republic was falling into anarchy and chaos. The other twelve states had faced similar economic and political difficulties, and continuing problems seemed to indicate that on a national level, an unwelcome democratic impulse was driving the population. Letters complaining of Shays’ Rebellion reached George Washington and convinced him to come out of retirement and lead the convention called for by Alexander Hamilton to amend the Articles of Confederation in order to deal with insurgencies like the one in Massachusetts and provide greater stability in the United States.

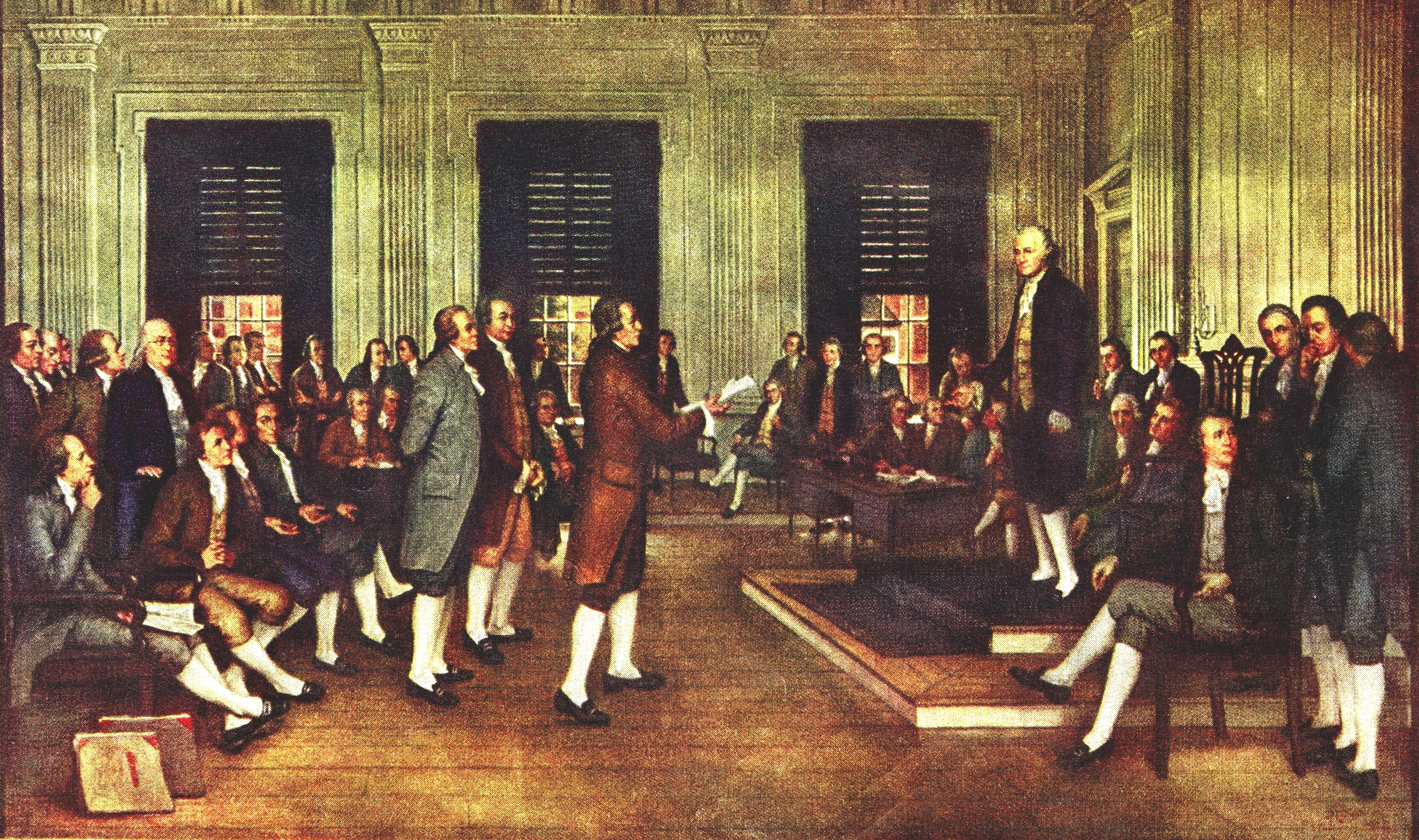

The stated purpose of the Philadelphia Convention in 1787 was to amend the Articles of Confederation. Very quickly, however, the attendees decided to create a new framework for a national government. Fifty-five men met in Philadelphia in secret; historians know of the proceedings only because James Madison kept careful notes of what transpired. The delegates knew that what they were doing would be controversial. Rhode Island refused to send delegates, and New Hampshire’s delegates arrived late. Two delegates from New York, Robert Yates and John Lansing, left the convention when it became clear that the Articles were being put aside and a new plan of national government was being drafted. They did not believe the delegates had the authority to create a strong national government.

One issue that the delegates in Philadelphia addressed was the way in which representatives to the new national government would be chosen. Would individual citizens be able to elect representatives or would representatives be chosen by state legislatures? And how much representation was appropriate for each state? James Madison put forward a proposition known as the Virginia Plan, which called for a strong national government that could overturn state laws. Madison’s plan featured a bicameral or two-house legislature, with an upper and a lower house. The number of representatives in both houses would be based on population. Virginia, the most populous state, would dominate national political power and ensure its interests, including slavery, would be safe. William Paterson introduced a New Jersey Plan to counter Madison’s scheme, proposing that all states have equal votes in a unicameral national legislature. He also addressed the economic problems of the day by calling for the Congress to have the power to regulate commerce, to raise revenue though taxes on imports and through postage, and to enforce Congressional requisitions from the states. Roger Sherman from Connecticut offered what became known as the Great Compromise, outlined a different bicameral legislature in which the upper house, the Senate, would have equal representation with each state represented by two senators chosen by the state legislatures. Only the lower house, the House of Representatives, would have proportional representation.

The question of slavery was a major issue at the Constitutional Convention because slaveholders wanted slaves to be counted along with whites, termed “free inhabitants,” when determining a state’s total population. This, in turn, would augment the number of representatives accorded to those states in the lower house. Some northerners such as New York’s Gouverneur Morris, hated slavery and did not even want the term included in the new national plan of government. The issue of counting for purposes of representation connected directly to the question of taxation. Beginning in 1775, the amount each state was assessed to support the Revolutionary War by the Second Continental Congress was determined by a state’s total population, including both free and enslaved individuals. States routinely fell far short of delivering the money requested by Congress under the plan. In April 1783, the Confederation Congress amended the earlier system of requisition by having slaves count as three-fifths of the white population. In this way, slaveholders gained a significant tax break. The delegates in Philadelphia adopted this same three-fifths formula in the summer of 1787. Northerners agreed to the three-fifths compromise because the Northwest Ordinance of 1787 had banned slavery in the future states of the northwest. Northern delegates felt this ban balanced political power between states with slaves and those without. The three-fifths compromise gave an advantage to slaveholders, but over time the growing population of the Northwest Territory would shift the balance of power.

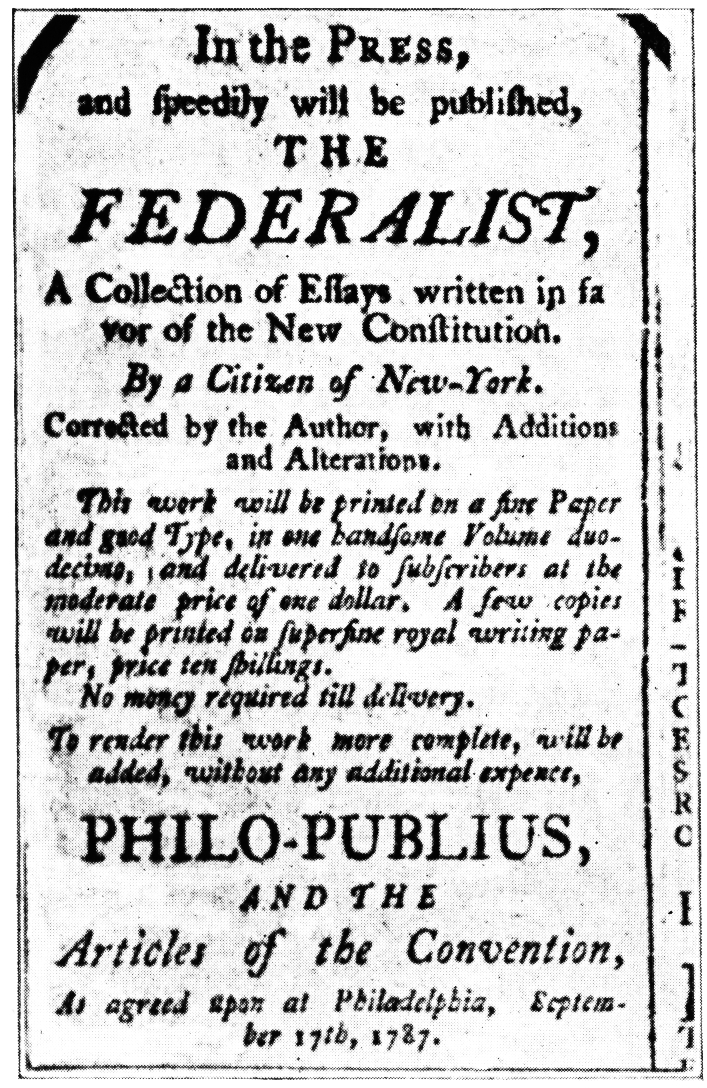

The draft constitution was finished in September 1787. The delegates decided that when nine of the thirteen states had approved the plan, the new government would go into effect. American public opinion was deeply divided, but most people were opposed. The architects of the new national government began a campaign to sway public opinion in favor of their blueprint for a strong central government. In the fierce debate that erupted, the two sides articulated contrasting visions of the American republic and of democracy. Federalist supporters of the 1787 Constitution made the case that a centralized republic provided the best hope for the nation’s survival. Those who opposed it, known as Anti-Federalists, argued that the Constitution would consolidate all power in a national government and rob the states of the power to make their own decisions. Anti-Federalists argued that wealthy aristocrats would run the new national government and that the political elite would not represent ordinary citizens. The rich would monopolize power and use the new government to pass laws that benefited their class interests. They also argued that after the experience of the Revolution and the difficulties of the Confederacy, the Constitution should contain a bill of rights. The Federalists, particularly John Jay, Alexander Hamilton, and James Madison, put their case to the public in a famous series of essays known as The Federalist Papers. These were first published in New York and subsequently republished elsewhere in the United States.

JAMES MADISON ON THE BENEFITS OF REPUBLICANISM

From this view of the subject, it may be concluded, that a pure Democracy, by which I mean a Society consisting of a small number of citizens, who assemble and administer the Government in person, can admit of no cure for the mischiefs of faction. A common passion or interest will, in almost every case, be felt by a majority of the whole; a communication and concert result from the form of Government itself; and there is nothing to check the inducements to sacrifice the weaker party, or an obnoxious individual. Hence it is, that such Democracies have ever been spectacles of turbulence and contention; have ever been found incompatible with personal security, or the rights of property; and have in general been as short in their lives, as they have been violent in their deaths. Theoretic politicians, who have patronized this species of Government, have erroneously supposed, that by reducing mankind to a perfect equality in their political rights, they would, at the same time, be perfectly equalized and assimilated in their possessions, their opinions, and their passions.

A Republic, by which I mean a Government in which the scheme of representation takes place, opens a different prospect, and promises the cure for which we are seeking. Let us examine the points in which it varies from pure Democracy, and we shall comprehend both the nature of the cure, and the efficacy which it must derive from the Union.

The two great points of difference, between a Democracy and a Republic, are, first, the delegation of the Government, in the latter, to a small number of citizens elected by the rest: Secondly, the greater number of citizens, and greater sphere of country, over which the latter may be extended.

Federalist No. 10

Including all the state ratifying conventions around the country, a total of about two thousand state delegates voted on whether to adopt the new plan of government. They represented the the decisions of state citizens who met and debated the document in their home communities. Many of these town meetings gave tentative approval and sent lists of items they wanted changed or amendments they wanted added. Much of the time, their suggestions were put aside and their provisional “Yes” votes were entered as approval. In the end, the Constitution only narrowly won ratification. In New York, the vote was thirty in favor to twenty-seven opposed. In Massachusetts, the vote to approve was 187 to 168, and some claim supporters of the Constitution resorted to bribes in order to ensure approval. Virginia ratified by a vote of eighty-nine to seventy-nine, and Rhode Island by thirty-four to thirty-two. Opposition to the Constitution reflected the fears that a new national government, much like the British monarchy, created too much centralized power and deprived citizens in the various states of the ability to make their own decisions. In June 1788, New Hampshire became the ninth state to ratify the federal Constitution, and elections for the first U.S. Congress were held in 1788 and 1789. In a reflection of the trust placed in him as the personification of republican virtue, George Washington became the first president in April 1789. John Adams served as his vice president; the pairing of a leader from Virginia with one from Massachusetts symbolized national unity. Nonetheless, political divisions quickly became apparent. Although they believed they were above partisan considerations, Washington and Adams represented the Federalist position in the just-ended fight over ratification, creating a backlash among the large segment of the people who resisted the new government’s assertions of federal power.

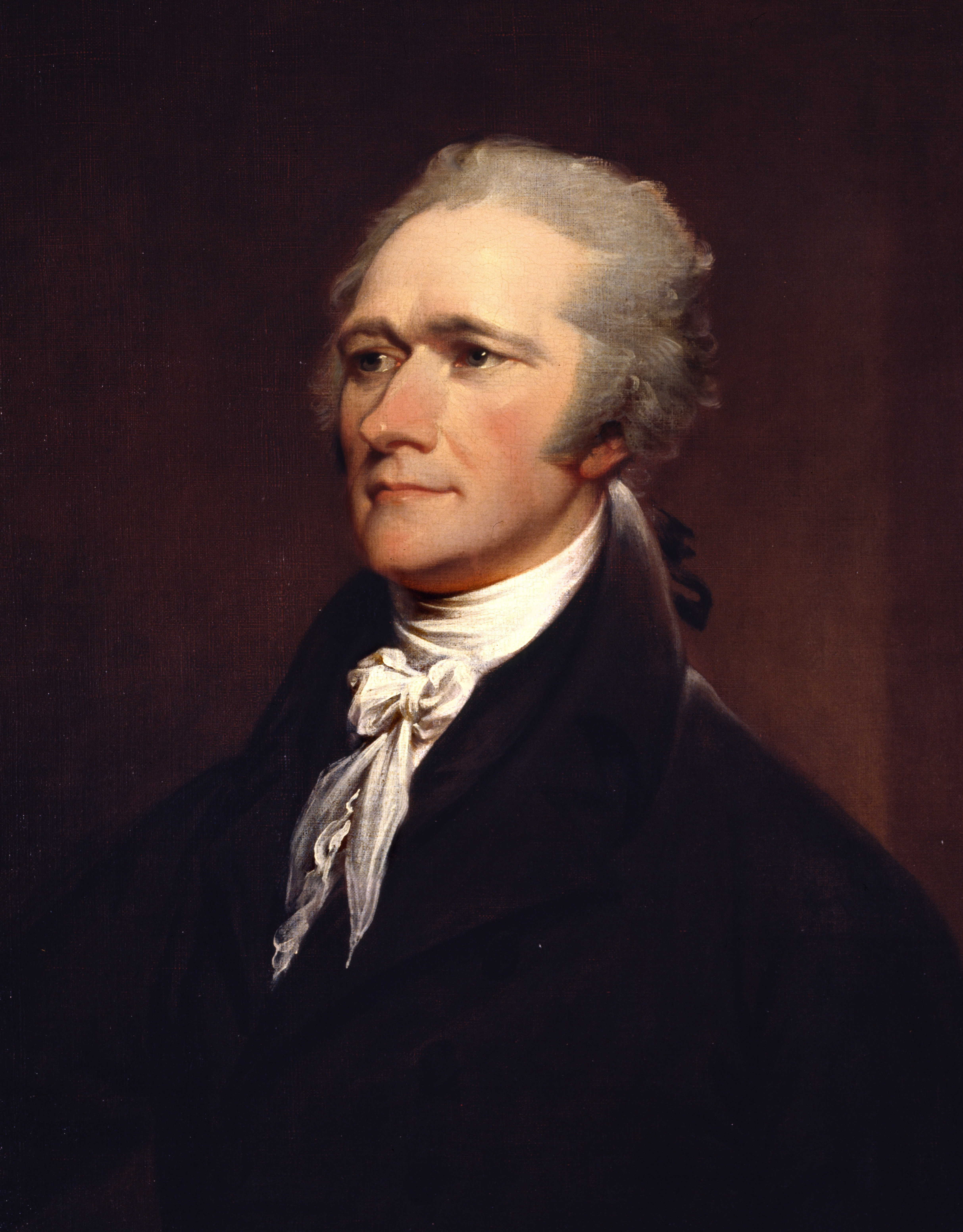

Though the Revolution had overthrown British aristocratic rule in the United States, Federalists adhered to a very British notion of social hierarchy. For Federalists, political participation was based on property, which barred many citizens from voting or holding office. Federalists did not believe the Revolution had changed the traditional social divisions between rich and poor, men and women, or between whites and other races. They did believe in clear distinctions in rank and intelligence. To these supporters of the Constitution, the idea that all were equal appeared ludicrous. Women, blacks, and Indians had to know their place as secondary to white male citizens. Attempts to impose equality would destroy the republic. The United States was not created to be a democracy. The writers and advocates of the Constitution held a majority among the members of the new national government. Many assumed the new executive posts the first Congress created. Washington appointed Alexander Hamilton, a leading Federalist, as secretary of the treasury. In July 1789, Congress also passed the Judiciary Act, creating a Supreme Court of six justices. Congress passed its first major piece of legislation by taxing imports with the 1789 Tariff Act. Congress also placed a fifty-cent-per-ton duty on materials transported by foreign ships coming into American ports, a move designed to give the commercial advantage to American shipping and goods.

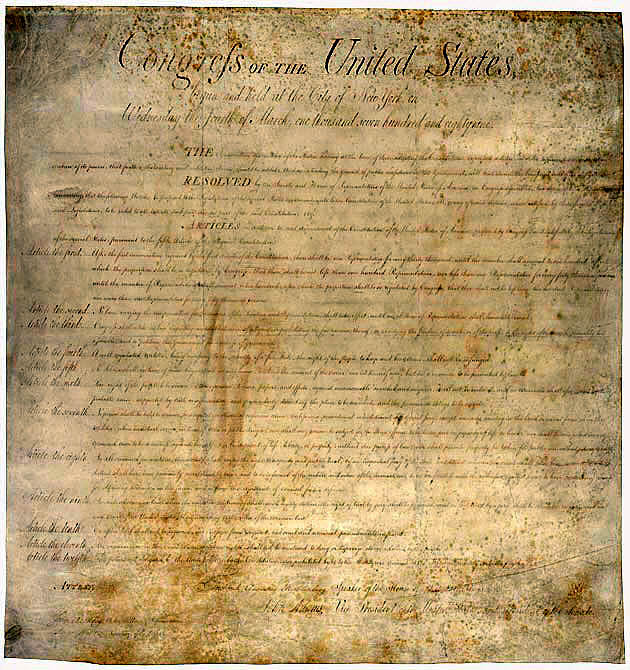

Almost half of Americans opposed the 1787 Constitution because it seemed a dangerous concentration of centralized power that threatened the rights and liberties of ordinary citizens. These opponents, known collectively as Anti-Federalists, united in demanding protections for individual rights and several states made the passing of a bill of rights a condition of their acceptance of the Constitution. Rhode Island and North Carolina rejected the Constitution because it did not already have this specific bill of rights. Federalists followed through on the promise they had made in their campaigning for the Constitution when Virginia Representative James Madison introduced and Congress approved the Bill of Rights. Adopted in 1791, the bill consisted of the first ten amendments to the Constitution and affirmed many of the personal rights state constitutions had already guaranteed.

| Rights Protected by the First Ten Amendments | |

| Amendment 1 | Right to freedoms of religion and speech; right to assemble and to petition the government for redress of grievances |

| Amendment 2 | Right to keep and bear arms to maintain a well-regulated militia |

| Amendment 3 | Right not to house soldiers during time of war |

| Amendment 4 | Right to be secure from unreasonable search and seizure |

| Amendment 5 | Rights in criminal cases, including to due process and indictment by grand jury for capital crimes, as well as the right not to testify against oneself |

| Amendment 6 | Right to a speedy trial by an impartial jury |

| Amendment 7 | Right to a jury trial in civil cases |

| Amendment 8 | Right not to face excessive bail or fines, or cruel and unusual punishment |

| Amendment 9 | Rights retained by the people, even if they are not specifically enumerated by the Constitution |

| Amendment 10 | States’ rights to powers not specifically delegated to the federal government |

Alexander Hamilton, Washington’s secretary of the treasury, was an ardent nationalist who believed a strong federal government could solve many of the new country’s financial ills. In 1789 the United States federal debt was over $53 million. The states had a combined debt of around $25 million, and the nation had been unable to pay its debts in the 1780s and was considered a credit risk by European countries. Hamilton wrote three reports offering solutions to the economic crisis brought on by these problems. The first addressed public credit, the second addressed banking, and the third addressed raising revenue. Hamilton’s Report on Public Credit recommended that the new federal government honor all its debts, including all paper money issued by the Confederation and the states during the war, at face value. Hamilton wanted wealthy American creditors who held large amounts of paper money to be invested, literally, in the new national government. Hamilton proposed that the federal government sell bonds to the public that would yield interest payments. Creditors could exchange their old notes for the new government bonds. Hamilton wanted to satisfy creditors, citing the goal of “doing justice to the creditors of the nation.” But the majority of both Confederation and state notes had found their way into the hands of speculators who had bought them from hard-pressed veterans in the 1780s at a fraction of their face value. Because these speculators held so many notes, many in Congress objected that Hamilton’s plan would benefit them at the expense of the original note-holders. One of those who opposed Hamilton’s 1790 report was James Madison, who questioned the fairness of a plan that seemed to cheat poor soldiers.

States with a large debt like South Carolina supported Hamilton’s plan, while states with less debt like North Carolina did not. Hamilton worked out a compromise with Virginians Madison and Jefferson, where in return for their support he would give up New York City as the nation’s capital and agree on a more southern location, which they preferred. In July 1790, a site along the Potomac River was selected as the new “federal city,” which became the District of Columbia. Hamilton’s plan to convert notes to bonds worked extremely well to restore European confidence in the U.S. economy. It also proved a windfall for creditors and for speculators who had bought up state and Confederation notes at far less than face value. But it immediately generated controversy about the size and scope of the government. Some saw the plan as an unjust use of federal power, and their objections increased when Hamilton proposed a Bank of the United States modeled on the Bank of England. The bank would issue loans to American merchants and federal bank notes while serving as a repository of government revenue from the sale of land. Jefferson, in particular, argued that the Constitution did not permit the creation of a national bank. In response, Hamilton invoked the Constitution’s implied powers. President Washington backed Hamilton’s position and signed legislation creating the bank in 1791. Finally, using the power to tax as provided under the Constitution, Hamilton decided to tax American-made whiskey and in 1791 Congress authorized a tax of 7.5 cents per gallon of whiskey and rum. Although many citizens paid what they considered a “sin tax” on an unneeded luxury, trouble erupted in four western Pennsylvania counties in an uprising known as the Whiskey Rebellion.

Farmers in the western counties of Pennsylvania produced whiskey from their grain for economic reasons. Without adequate roads to transport a bulky grain harvest, frontier farmers distilled their grains into less bulky spirits that were more cost-effective to transport and had a higher value at a lower mass. Since these farmers depended on the sale of whiskey for the cash they used to buy goods they couldn’t produce on their farms (as well as pay their taxes), many citizens in western Pennsylvania viewed the new tax as further proof that the new Federalist government favored the commercial classes on the coast at the expense of farmers in the West. Supporters of the tax argued that it helped stabilize the economy and that its cost could easily be passed on to consumers by raising prices, and would not be paid by the farmer-distiller. But the tax collectors were still trying to take money out of the farmers’ pockets and there was no guarantee they would be able to sell the whiskey at higher prices. In 1794 angry citizens rebelled against the federal officials enforcing the federal law. Like the Sons of Liberty before the American Revolution and the Massachusetts regulators of Shays’s Rebellion, the whiskey rebels used violence to protest policies they saw as unfair. They tarred and feathered federal officials, intercepted the federal mail, and intimidated wealthy citizens. The extent of their discontent was represented most extremely by talk of forming an independent western commonwealth, and they even began negotiations with British and Spanish representatives, hoping to secure their support for independence from the United States. The rebels also contacted their backcountry neighbors in Kentucky and South Carolina, circulating the idea of secession. George Washington led a force of 13,000 men; the only time a US President has ever led an army in the field and the only time a Commander in Chief has ever taken the field against US citizens.