209 Proposed Intervention in Cuba (1875)

Hamilton Fish was a Governor of New York and a US Senator before the Civil War; then he was Secretary of State during both of President Grant’s administrations. Diplomatic negotiations with Spain concerning Cuba began soon after the United States acknowledged the independence of the South and Central American States and these questions remained unresolved until they finally culminated, in 1898, in war between the two nations. This extract is from an official letter to Caleb Cushing, the American minister to Spain.

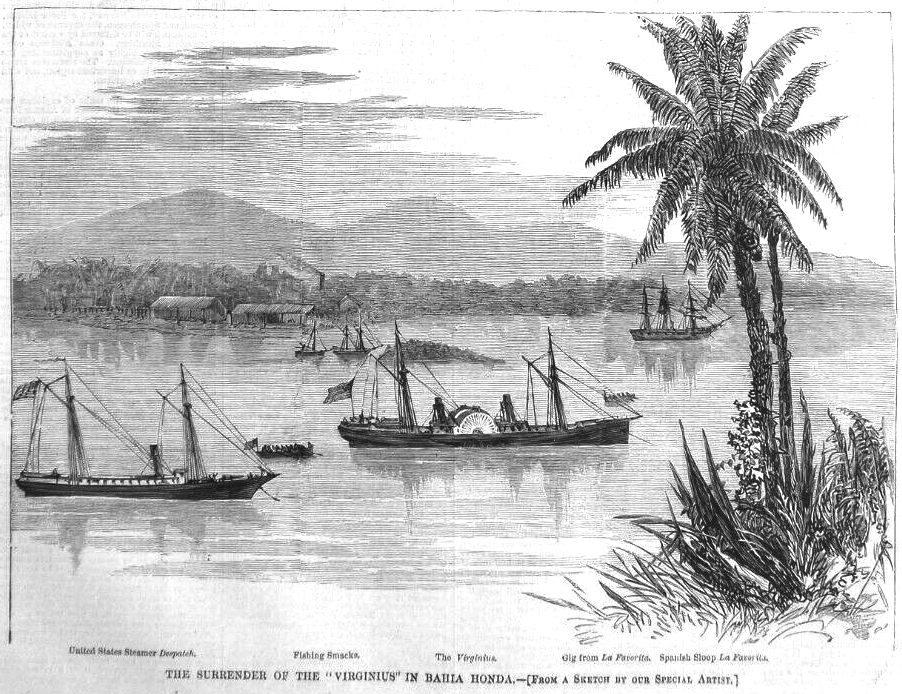

The Virginius was an American ship hired by Cuban insurrectionists to transport men and munitions. After the US Civil War, Cuba was still part of the Spanish Empire and was one of the few places in the Western Hemisphere where slavery was still practiced. The Virginius was captured by the Spanish General Burriel, who declared the people on board to be pirates and executed 53 men until the British government intervened. Many of the executed men were American citizens, and protest rallies were held in several American cities, calling for US intervention in Cuba and punishment of Spain.

Apart from the general question of the unsatisfactory condition of affairs in Cuba and the failure to suppress the revolution, several prominent questions remained unadjusted, the settlement of which was deemed necessary before any satisfactory relations with Spain could be established or maintained. Upon all of these you were instructed. The most prominent among them were the questions arising from the embargo and confiscation of estates of American citizens in Cuba; those relating to the trial of American citizens in that island, in violation of treaty obligations, and the claims arising out of the capture of the Virginius, including the trial and punishment of General Burriel.

In the cases of embargo and confiscation, not only have wrongs been long since done, but continuing and repeated wrongs are daily inflicted. Turning to the questions which arose from the capture of the Virginius, and the executions which followed, no extended reference is required. The particulars of the delivery of the vessel to this Government, and the payment to both Great Britain and the United States of considerable sums as compensation for the acts of the authorities in ordering the execution of fifty-three of the passengers and crew under circumstances of peculiar brutality, have passed into history. So far as a payment of money can atone for the execution of these unprotected prisoners, that has been accomplished. The higher and more imperative duty which the government of Spain assumed by the protocol of November 29, 1873, namely, to bring to justice General Burriel and the other principal offenders in this tragedy, has been evaded and entirely neglected.

It was then more than five years since an organized insurrection had broken out which the government of Spain had been entirely unable to suppress. Almost two years have passed since those instructions were issued, and it would appear that the situation has in no respect improved. The horrors of war have in no perceptible measure abated; the inconveniences and injuries which we then suffered have remained, and others have been added. The ravages of war have touched new parts of the island, and well-nigh ruined its financial and agricultural system and its relations to the commerce of the world. No effective steps have been taken to establish reforms or remedy abuses, and the effort to suppress the insurrection, by force alone, has been a complete failure.

The United States purchases more largely than any other people of the productions of the island of Cuba and therefore, more than any other for this reason, and still more by reason of its immediate neighborhood, is interested in the arrest of a system of wanton destruction which disgraces the age and affects every commercial people on the face of the globe. Under these circumstances and in view of the fact that Spain has rejected all suggestions of reform or offers of mediation made by this Government, and has refused all measures looking to a reconciliation, except on terms which make reconciliation an impossibility, the difficulty of the situation becomes increased.

When, however, in addition to these general causes of difficulty, we find the Spanish government neglectful also of the obligations of treaties and solemn compacts, and unwilling to afford any redress for long-continued and well-founded wrongs suffered by our citizens, it becomes a serious question how long such a condition of things can or should be allowed to exist, and compels us to inquire whether the point has not been reached where longer endurance ceases to be possible.

During all this time and under these aggravated circumstances, this Government has not failed to perform her obligations to Spain as scrupulously as toward other nations. It will be apparent that such a state of things cannot continue. It is absolutely necessary to the maintenance of our relations with Spain, even on their present footing, that our just demands for the return to citizens of the United States of their estates in Cuba, unencumbered, and for securing to them a trial for offenses according to treaty provisions and all other rights guaranteed by treaty and by public law, should be complied with.

The United States has exerted itself to the utmost, for seven years, to repress unlawful acts on the part of these self-exiled subjects of Spain, relying on the promise of Spain to pacify the island. Seven years of strain on the powers of this Government to fulfill all that the most exacting demands of one government can make, under any doctrine or claim of international obligation, upon another, have not witnessed the much hoped for pacification. The United States feels itself entitled to be relieved of this strain. The severe measures, injurious to the United States and often in conflict with public law, which the colonial officers have taken to subdue the insurrection; the indifference and ofttimes the offensive assaults upon the just susceptibilities of the people of the United States and their Government, which have characterized that portion of the peninsular population of Havana which has sustained and upheld, if it has not controlled, successive governors-general, and which have led to the disregard of orders and decrees which the more enlarged wisdom and the more friendly councils of the home government had enacted; the cruelty and inhumanity which have characterized the contest, both on the part of the colonial government and of the revolt, for seven years, and the destruction of valuable properties and industries by arson and pillage, which Spain appears unable, however desirous, to prevent and stop, in an island three thousand miles distant from her shores, but lying within sight of our coast, with which trade and constant intercourse are unavoidable, are causes of annoyance and of injury to the United States, which a people cannot be expected to tolerate without the assured prospect of their termination.

The United States has more than once been solicited by the insurgents to extend to them its aid, but has for years hitherto resisted such solicitation and has endeavored by the tender of its good offices, in the way of mediation, advice, and remonstrance, to bring to an end a great evil which has pressed sorely upon the interests both of the Government and of the people of the United States, as also upon the commercial interests of other nations. The President hopes that Spain may spontaneously adopt measures looking to a reconciliation and to the speedy restoration of peace, and the organization of a stable and satisfactory system of government in the island of Cuba.

In the absence of any prospect of a termination of the war, or of any change in the manner in which it has been conducted on either side, he feels that the time is at hand when it may be the duty of other governments to intervene, solely with the view of bringing to an end a disastrous and destructive conflict and of restoring peace in the island of Cuba. No government is more deeply interested in the order and peaceful administration of this island than is that of the United States, and none has suffered as has the United States from the condition which has obtained there during the past six or seven years. He will, therefore, feel it his duty at an early day to submit the subject in this light, and accompanied by an expression of the views above presented, for the consideration of Congress.

It is believed to be a just and friendly act to frankly communicate this conclusion to the Spanish government. You will, therefore, take an early occasion thus to inform that government.

Source: Hamilton Fish, House Executive Documents, 44th Congress, 1st session. (Washington, 1876), XII, No. 99, pp. 3-11. https://archive.org/details/americanhistoryt04hartuoft/page/556/mode/2up