191 Pickett’s Charge at Gettysburg (1863)

General Lee has reported of arrangements for the day:

The general plan was unchanged. Longstreet, reinforced by Pickett’s three brigades which arrived near the battlefield during the afternoon of the 2nd [July] was ordered to attack the next morning and General Ewell was ordered to attack the enemy’s right at the same time.

This is disingenuous. He did not give or send me orders for the morning of the third day, nor did he reinforce me by Pickett’s brigades for morning attack. As his headquarters were about four miles from the command, I did not ride over but sent to report the work of the second day. In the absence of orders, I had scouting parties out during the night in search of a way by which we might strike the enemy’s left and push it down towards his center. I found a way that gave some promise of results and was about to move the command, when he rode over after sunrise and gave his orders. His plan was to assault the enemy’s left center by a column to be composed of McLaws’s and Hood’s divisions reinforced by Pickett’s brigades. I thought that it would not do; that the point had been fully tested the day before by more men when all were fresh. That the enemy was there looking for us, as we heard him during the night putting up his defenses. That the divisions of McLaws and Hood were holding a mile along the right of my line against twenty thousand men who would follow their withdrawal, strike the flank of the assaulting column, crush it, and get on our rear towards the Potomac River. That thirty thousand men was the minimum of force necessary for the work. That even such force would need close co-operation on other parts of the line. That the column as he proposed to organize it would have only about thirteen thousand men (the divisions having lost a third of their numbers the day before). That the column would have to march a mile under concentrating battery fire and a thousand yards under long-range musketry. That the conditions were different from those in the days of Napoleon, when field batteries had a range of six hundred yards and musketry about sixty yards.

He said the distance was not more than fourteen hundred yards. General Meade’s estimate was a mile or a mile and a half. He then concluded that the divisions of McLaws and Hood could remain on the defensive line; that he would reinforce by divisions of the Third Corps and Pickett’s brigades and stated the point to which the march should be directed. I asked the strength of the column. He stated fifteen thousand. Opinion was then expressed that the fifteen thousand men who could make successful assault over that field had never been arrayed for battle. But he was impatient of listening and tired of talking and nothing was left but to proceed. General Alexander was ordered to arrange the batteries of the front of the First and Third Corps, those of the Second were supposed to be in position. Colonel Walton was ordered to see that the batteries of the First were supplied with ammunition and to prepare to give the signal-guns for the opening combat. The infantry of the Third Corps to be assigned were Heth’s and Pettigrew’s divisions and Wilcox’s brigade.

The signal-guns broke the silence, the blaze of the second gun mingling in the smoke of the first, and salvoes roiled to the left and repeated themselves, the enemy’s fine metal spreading its fire to the converging lines, ploughing the trembling ground, plunging through the line of batteries and clouding the heavy air. The two or three hundred guns seemed proud of their undivided honors and organized confusion. The Confederates had the benefit of converging fire into the enemy’s massed position but the superior metal of the enemy neutralized the advantage of position. The brave and steady work progressed.

Pickett said, “General, shall I advance?” The effort to speak the order failed and I could only indicate it by an affirmative bow. He accepted the duty with seeming confidence of success, leaped on his horse, and rode gayly to his command. I mounted and spurred for Alexander’s post. He reported that the batteries he had reserved for the charge with the infantry had been spirited away by General Lee’s chief of artillery. That the ammunition of the batteries of position was so reduced that he could not use them in proper support of the infantry. He was ordered to stop the march at once and fill up his ammunition chests. But, alas! There was no more ammunition to be had.

The order was imperative. The Confederate commander had fixed his heart upon the work. Just then a number of the enemy’s batteries hitched up and hauled off, which gave a glimpse of unexpected hope. Encouraging messages were sent for the columns to hurry on, and they were then on elastic springing step. The officers saluted as they passed, their stern smiles expressing confidence. General Pickett, a graceful horseman, sat tightly in the saddle, his brown locks flowing quite over his shoulders. Pettigrew’s division spread their steps and quickly rectified the alignment and the grand march moved bravely on.

As soon as the leading columns opened the way, the supports sprang to their alignments. General Trimble mounted, adjusting his seat and reins with an air and grace as if setting out on a pleasant afternoon ride. When aligned to their places solid march was made down the slope and past our batteries of position.

Confederate batteries put their fire over the heads of the men as they moved down the slope and continued to draw the fire of the enemy until the smoke lifted and drifted to the rear, when every gun was turned upon the infantry columns. The batteries that had been drawn off were replaced by others that were fresh. Soldiers and officers began to fall, some to rise no more, others to find their way to the hospital tents. Single files were cut here and there, then the gaps increased and an occasional shot tore wider openings, But, closing the gaps as quickly as made, the march moved on.

Colonel Latrobe was sent to General Trimble to have his men fill the line of the broken brigades, and bravely they repaired the damage. The enemy moved out against the supporting brigade in Pickett’s rear. Colonel Sorrel was sent to have that move guarded and Pickett was drawn back to that contention. McLaws was ordered to press his left forward, but the direct line of infantry and cross-fire of artillery was telling fearfully on the front. Colonel Fremantle ran up to offer congratulations on the apparent success, but the big gaps in the ranks grew until the lines were reduced to half their length. I called his attention to the broken, struggling ranks. Trimble mended the battle of the left in handsome style but on the right the massing of the enemy grew stronger and stronger. Brigadier Garnett was killed, Kemper and Trimble were desperately wounded. Generals Hancock and Gibbon were wounded. General Lane succeeded Trimble and with Pettigrew held the battle of the left in steady ranks.

Pickett’s lines being nearer, the impact was heaviest upon them. Most of the field officers were killed or wounded. Colonel Whittle of Armistead’s brigade, who had been shot through the right leg at Williamsburg and lost his left arm at Malvern Hill, was shot through the right arm, then brought down by a shot through his left leg.

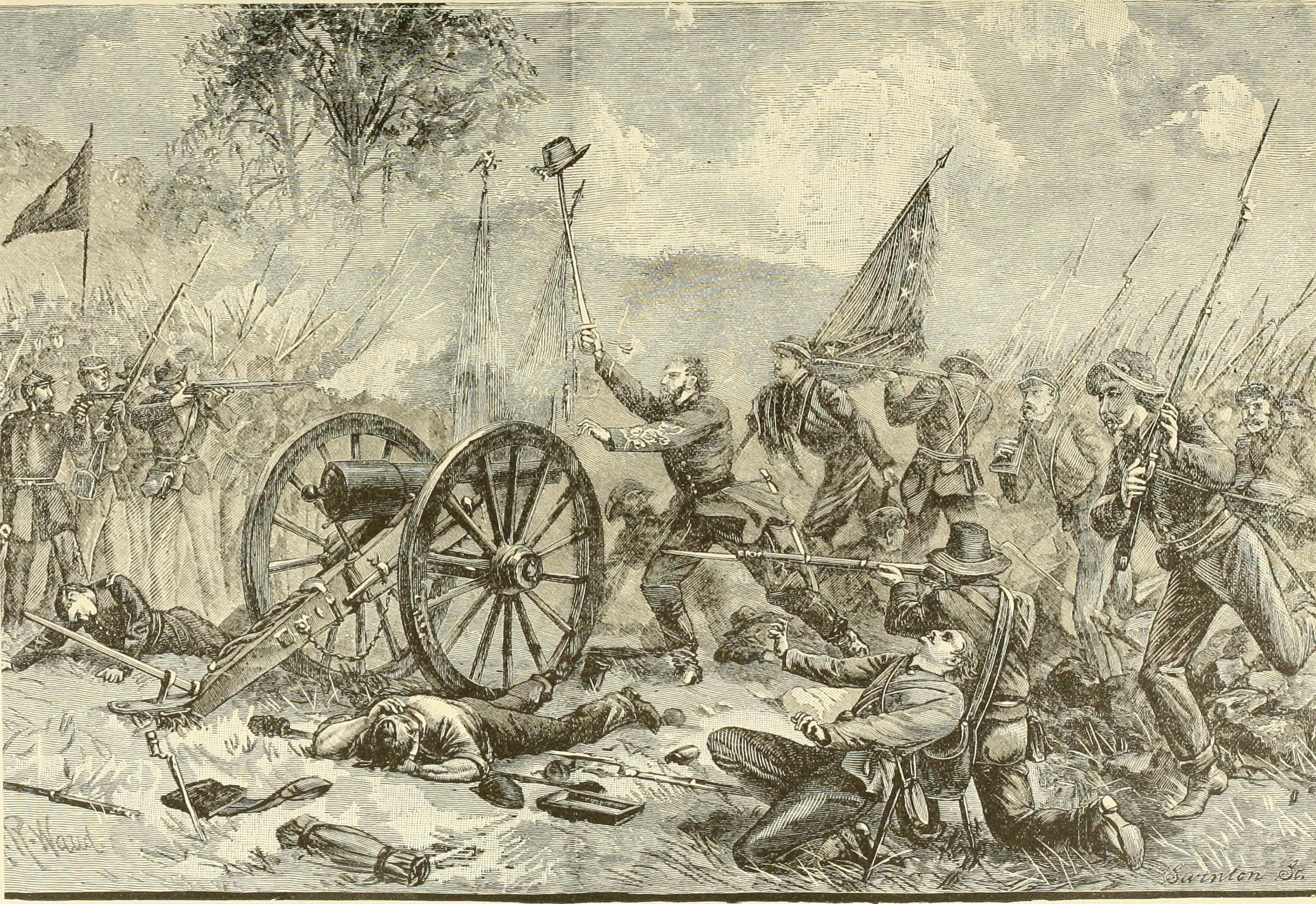

General Armistead, of the second line, spread his steps to supply the places of fallen comrades. His colors cut down with a volley against the bristling line of bayonets, he put his cap on his sword to guide the storm. The enemy’s massing, enveloping numbers held the struggle until the noble Armistead fell beside the wheels of the enemy’s battery. Pettigrew was wounded but held his command. General Pickett, finding the battle broken while the enemy was still reinforcing, called the troops off. There was no indication of panic. The broken files marched back in steady step. The effort was nobly made and failed from blows that could not be fended.

Looking confidently for advance of the enemy through our open field, I rode to the line of batteries, resolved to hold it until the last gun was lost. As I rode, the shells screaming over my head and ploughing the ground under my horse, an involuntary appeal went up that one of them might take me from scenes of such awful responsibility. But the storm to be met left no time to think of one’s self. The battery officers were prepared to meet the crisis. No move had been made for leaving the field. Our men passed the batteries in quiet walk.

Source: James Longstreet, From Manassas to Appomattox (1896), 385-395. https://archive.org/details/americanhistoryt00ivunse/page/372/mode/2up