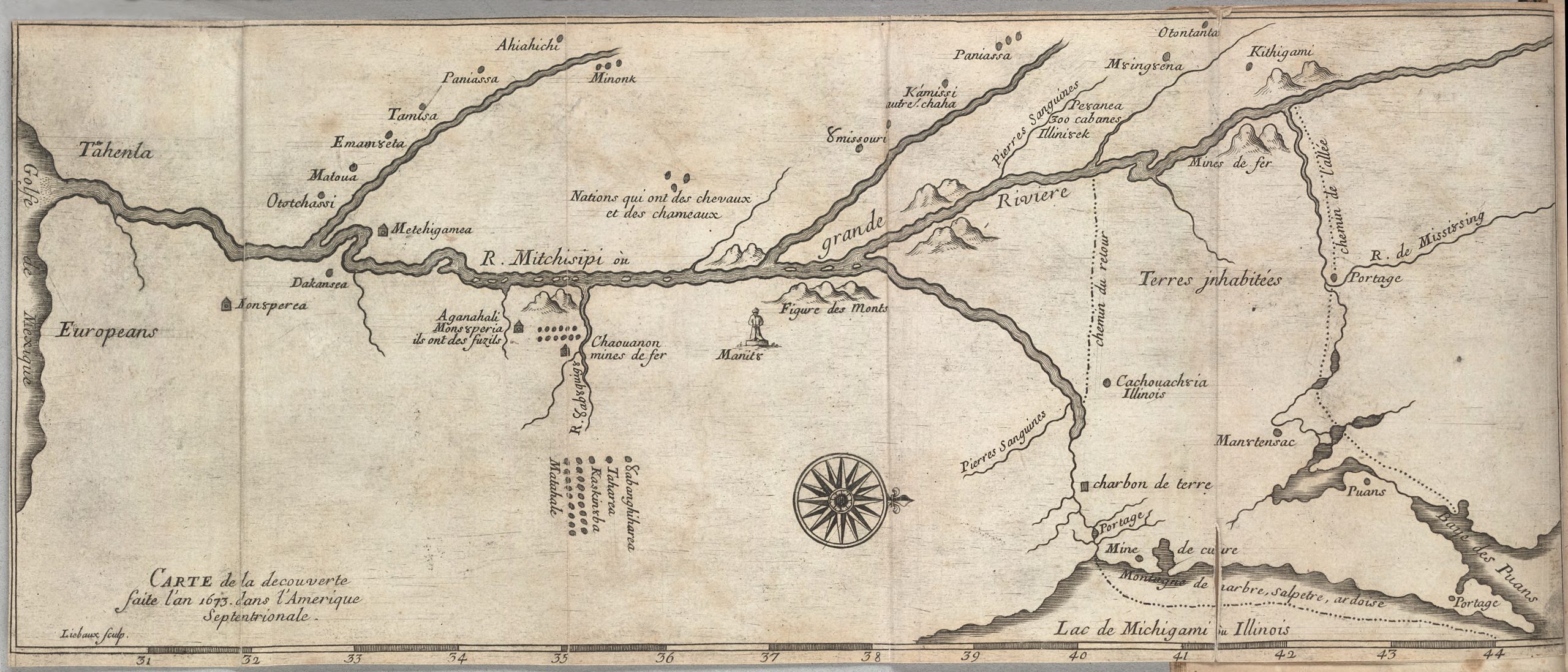

37 Marquette on the Mississippi (1673)

Jacques Marquette (1637-1675) was a Jesuit priest who migrated to New France in 1666 and was assigned to Trois-Rivières on the St. Lawrence River, to do missionary work among the Indians. After two years, he moved to the Great Lakes region and in 1669 he was assigned to a mission in the Apostle Islands of Lake Superior. He travelled 500 miles by canoe; two years later he established the St. Ignace Mission on Mackinac Island. In 1673 Marquette took a leave from missionary work to join an expedition down the Mississippi with Louis Jolliet. They went as far as the Arkansas River and then wintered in what would become Chicago. Marquette lost his papers on the return journey, and composed this narrative from memory.

I embarked with Mr. Joliet, who had been chosen to conduct this enterprise, on the 13th May 1673 with five other Frenchmen in two bark canoes. We laid in some Indian corn and smoked beef for our voyage. We first took care, however, to draw from the Indians all the information we could concerning the countries through which we designed to travel and drew up a map on which we marked down the rivers, nations, and points of the compass to guide us in our journey. The first nation we came to was called the Folles-Avoines or the nation of wild oats. I entered their river to visit them, as I had preached among them some years before. The wild oats from which they derive their name grow spontaneously in their country.

I acquainted them with my design of discovering other nations to preach to them the mysteries of our holy religion, at which they were much surprised and said all they could to dissuade me from it. They told me I would meet Indians who spare no strangers and whom they kill without any provocation or mercy. That the war they have one with the other would expose me to be taken by their warriors, as they are constantly on the look-out to surprise their enemies. That the Great River was exceedingly dangerous and full of frightful monsters who devoured men and canoes together, and that the heat was so great that it would positively cause our death. I thanked them for their kind advice but told them I would not follow it, as the salvation of a great many souls was concerned in our undertaking, for whom I should be glad to lose my life.

This bay [Green Bay] is about thirty leagues long and eight broad in the greatest breadth. We left this bay to go into a river [Fox River] that discharges itself therein. It abounds in bustards, ducks, and other birds which are attracted there by the wild oats, of which they are very fond. We next came to a village of the Maskoutens, or nation of fire. We were informed that at three leagues from the Maskoutens we should find a river which runs into the Mississippi, and that we were to go to the west-south-west to find it. The river upon which we rowed and had to carry our canoes from one to the other, looked more like a cornfield than a river, insomuch that we could hardly find its channel. We now left the waters which extend to Quebec, about five or six hundred leagues, to take those which would leads us hereafter into strange lands.

The river upon which we embarked is called Mesconsin [Wisconsin]. The river is very wide but the sand bars make it very difficult to navigate. The country through which it flows is beautiful; the groves are full of walnut, oak, and other trees unknown to us in Europe. We saw neither game nor fish, but roebuck and buffaloes in great numbers. After having navigated thirty leagues we discovered some iron mines and one of our company who had seen such mines before said these were very rich in ore. After having rowed ten leagues further, making forty leagues from the place where we had embarked, we came into the Mississippi on the 17th of June [1673].

The mouth of the Mesconsin is in about 42° N. latitude. Behold us then, upon this celebrated river whose singularities I have attentively studied. The Mississippi takes its rise in several lakes in the North. Its channel is very narrow at the mouth of the Mesconsin and its current is slow because of its depth. In sounding we found nineteen fathoms of water. A little further on it widens nearly three-quarters of a league. Here we perceived the country change its appearance. There were scarcely any more woods or mountains. We met from time to time monstrous fish which struck so violently against our canoes that at first we took them to be large trees which threatened to upset us. When we threw our nets into the water we caught an abundance of sturgeons and another kind of fish like our trout.

Having descended the river as far as 41° 28′, we found that turkeys took the place of game and the Pisikious that of other animals. We called the Pisikious wild buffaloes because they very much resemble our domestic oxen, but twice as large. We shot one of them and it was as much as thirteen men could do to drag him from the place where he fell. We continued to descend the river, not knowing where we were going and having made a hundred leagues without seeing anything but wild beasts and birds. And being on our guard we landed at night to make our fire and prepare our repast and then left the shore to anchor in the river, while one of us watched by turns to prevent a surprise. We went south and south-west until we found ourselves in about the latitude of 40° and some minutes, having rowed more than sixty leagues since we entered the river.

We took leave of our guides about the end of June and embarked in presence of all the village, who admired our birch canoes as they had never before seen anything like them. We descended the river, looking for another called Pekitanoni [Missouri] which runs from the north-west into the Mississippi. As we were descending the river we saw high rocks with hideous monsters painted on them, and upon which the bravest Indians dare not look. They are as large as a calf, with head and horns like a goat, their eyes red, beard like a tiger’s, and a face like a man’s. Their tails are so long that they pass over their heads and between their fore legs, under their belly, and ending like a fish’s tail. They are painted red, green, and black. They are so well drawn that I cannot believe they were drawn by the Indians. And for what purpose they were made seems to me a great mystery.

As we fell down the river and while we were discoursing upon these monsters, we heard a great rushing and bubbling of waters and small islands of floating trees coming from the mouth of the Pekitanoni with such rapidity that we could not trust ourselves to go near it. The water of this river is so muddy that we could not drink it. It so discolors the Mississippi as to make the navigation of it dangerous. This river comes from the north-west and empties into the Mississippi, and on its banks are situated a number of Indian villages. We judged by the compass that the Mississippi discharged itself into the Gulf of Mexico. It would, however, have been more agreeable if it had discharged itself into the South Sea or Gulf of California.

Having satisfied ourselves that the Gulf of Mexico was in latitude 31° 40′, and that we could reach it in three or four days’ journey from the Akansea [Arkansas River], and that the Mississippi discharged itself into it and not to the eastward of the Cape of Florida nor into the California Sea, we resolved to return home. We considered that the advantage of our travels would be altogether lost to our nation if we fell into the hands of the Spaniards, from whom we could expect no other treatment than death or slavery. Besides, we saw that we were not prepared to resist the Indians, the allies of the Europeans, who continually infested the lower part of this river. We therefore came to the conclusion to return and make a report to those who had sent us. So that having rested another day, we left the village of the Akansea on the seventeenth of July 1673, having followed the Mississippi from the latitude 42° to 34° and preached the Gospel to the utmost of my power to the nations we visited. We then ascended the Mississippi with great difficulty against the current and left it in the latitude of 38° north to enter another river [Illinois], which took us to the lake of the Illinois [Michigan], which is a much shorter way than through the River Mesconsin by which we entered the Mississippi.

Source: “Discovery of the Mississippi” (1673) by James Marquette, Translated by J. D. B. De Bow, Marquette and Joliet’s Account of the Voyage to Discover the Mississippi River, in B. F. French, Historical Collections of Louisiana (Philadelphia, 1850), Part II, 279-296. https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.45493/page/n155/mode/2up