126 Justification of the War (1813)

The war was declared because Great Britain arrogated to herself the pretension of regulating foreign trade under the delusive name of retaliatory Orders in Council — a pretension by which she undertook to proclaim to American enterprise, “Thus far shalt thou go, and no farther.” Orders which she refused to revoke after the alleged cause of their enactment had ceased because she persisted in the act of impressing American seamen, because she had instigated the Indians to commit hostilities against us, and because she refused indemnity for her past injuries upon our commerce. But it is said that the Orders in Council are done away, no matter from what cause. And that having been the sole motive for declaring the war, the relations of peace ought to be restored.

The war was declared because Great Britain arrogated to herself the pretension of regulating foreign trade under the delusive name of retaliatory Orders in Council — a pretension by which she undertook to proclaim to American enterprise, “Thus far shalt thou go, and no farther.” Orders which she refused to revoke after the alleged cause of their enactment had ceased because she persisted in the act of impressing American seamen, because she had instigated the Indians to commit hostilities against us, and because she refused indemnity for her past injuries upon our commerce. But it is said that the Orders in Council are done away, no matter from what cause. And that having been the sole motive for declaring the war, the relations of peace ought to be restored.

I have no hesitation then in saying that I have always considered the impressment of American seamen as much the most serious aggression. But sir, how have those orders at last been repealed? Great Britain, it is true, has intimated a willingness to suspend their practical operation but she still arrogates to herself the right to revive them upon certain contingencies of which she constitutes herself the sole judge. She waives the temporary use of the rod but she suspends it in terrorem over our heads.

Supposing it was conceded to gentlemen that such a repeal of the Orders in Council as took place on the 23rd of June last, exceptionable as it is, being known before the war would have prevented the war. Does it follow that it ought to induce us to lay down our arms without the redress of any other injury? Does it follow in all cases, that that which would have prevented the war in the first instance should terminate the war? By no means. It requires a great struggle for a nation prone to peace as this is, to burst through its habits and encounter the difficulties of war. Such a nation ought but seldom to go to war. When it does, it should be for clear and essential rights alone and it should firmly resolve to extort, at all hazards, their recognition.

And who is prepared to say that American seamen shall be surrendered the victims to the British principle of impressment? It is in vain to assert the inviolability of the obligation of allegiance. It is in vain to set up the plea of necessity and to allege that she cannot exist without the impressment of her seamen. The truth is, she comes by her press gangs on board of our vessels, seizes our native seamen as well as naturalized and drags them into her service. It is the case then of the assertion of an erroneous principle and a practice not conformable to the principle — a principle which, if it were theoretically right, must be forever practically wrong. If Great Britain desires a mark by which she can know her own subjects, let her give them an ear mark. The colors that float from the mast-head should be the credentials of our seamen. There is no safety to us and the gentlemen have shown it, but in the rule that all who sail under the flag (not being enemies) are protected by the flag. It is impossible that this country should ever abandon the gallant tars who have won for us such splendid trophies.

The gentleman from Delaware sees in Canada no object worthy of conquest. Other gentlemen consider the invasion of that country as wicked and unjustifiable. Its inhabitants are represented as unoffending, connected with those of the bordering States by a thousand tender ties, interchanging acts of kindness and all the offices of good neighborhood. Canada innocent! Canada unoffending! Is it not in Canada that the tomahawk of the savage has been molded into its deathlike form? From Canadian magazines, Malden and others, that those supplies have been issued which nourish and sustain the Indian hostilities?

What does a state of war present? The united energies of one people arrayed against the combined energies of another. A conflict in which each party aims to inflict all the injury it can by sea and land upon the territories, property, and citizens of the other, subject only to the rules of mitigated war practiced by civilized nations. The gentlemen would not touch the continental provinces of the enemy nor I presume, for the same reason, her possessions in the West Indies. The same humane spirit would spare the seamen and soldiers of the enemy. The sacred person of His Majesty must not be attacked, for the learned gentlemen on the other side are quite familiar with the maxim that the King can do no wrong. Indeed sir, I know of no person on whom we may make war upon the principles of the honorable gentlemen, except Mr. Stephen, the celebrated author of the Orders in Council or the Board of Admiralty who authorize and regulate the practice of impressment.

The disasters of the war admonish us, we are told, of the necessity of terminating the contest. If our achievements upon the land have been less splendid than those of our intrepid seamen, it is not because the American soldier is less brave. On the one element, organization, discipline, and a thorough knowledge of their duties exist on the part of the officers and their men. On the other, almost everything is yet to be acquired. We have however the consolation that our country abounds with the richest materials and that in no instance when engaged in an action have our arms been tarnished. It is true that the disgrace of Detroit remains to be wiped off. With the exception of that event, the war even upon the land had been attended by a series of the most brilliant exploits which, whatever interest they may inspire on this side of the mountains, have given the greatest pleasure on the other.

What cause, Mr. Chairman, which existed for declaring the war has been removed? We sought indemnity for the past and security for the future. The Orders in Council are suspended, not revoked. No compensation for spoliations, Indian hostilities which were before secretly instigated now openly encouraged, and the practice of impressment unremittingly persevered in and insisted upon. Yet [the] Administration has given the strongest demonstrations of its love of peace. On the 29th of June, less than ten days after the declaration of war, the Secretary of State writes to Mr. Russell authorizing him to agree to an armistice upon two conditions only; and what are they? That the Orders in Council should be repealed and the practice of impressing American seamen cease, those already impressed being released. When Mr. Russell renews the overture in what was intended as a more agreeable form to the British Government, Lord Castlereagh is not content with a simple rejection, but clothes it in the language of insult.

The honorable gentleman from North Carolina (Mr. Pearson) supposes that if Congress would pass a law prohibiting the employment of British seamen in our service upon condition of a like prohibition on their part and repeal the act of non-importation, peace would immediately follow. Sir, I have no doubt if such a law were passed with all the requisite solemnities and the repeal to take place, Lord Castlereagh would laugh at our simplicity. No sir, [the] Administration has erred in the steps which it has taken to restore peace, but its error has been not in doing too little but in betraying too great a solicitude for that event. An honorable peace is attainable only by an efficient war. My plan would be to call out the ample resources of the country, give them a judicious direction, prosecute the war with the utmost vigor, strike wherever we can reach the enemy at sea or on land, and negotiate the terms of a peace at Quebec or Halifax. We are told that England is a proud and lofty nation that disdaining to wait for danger, meets it half-way. Haughty as she is, we once triumphed over her and if we do not listen to the councils of timidity and despair we shall again prevail. In such a cause with the aid of Providence, we must come out crowned with success. But if we fail, let us fail like men: lash ourselves to our gallant tars and expire together in one common struggle, fighting for “seamen’s rights and free trade.”

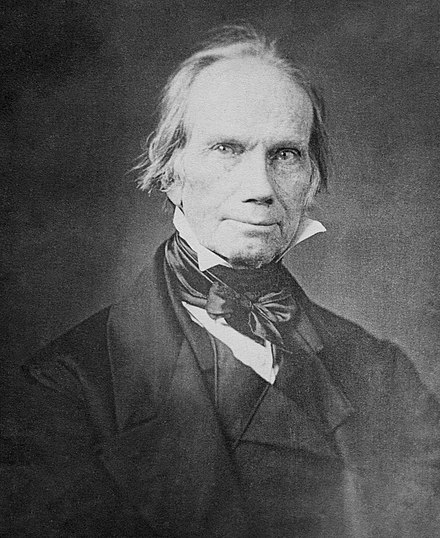

Source: “Justification of the War” (1813), by Henry Clay in Annals of Congress, 12th Congress, 2nd session. (1853), 667-676. https://archive.org/details/toldcontemporari03hartrich/page/416/mode/2up