25 Indentured Servant’s Letter (1623)

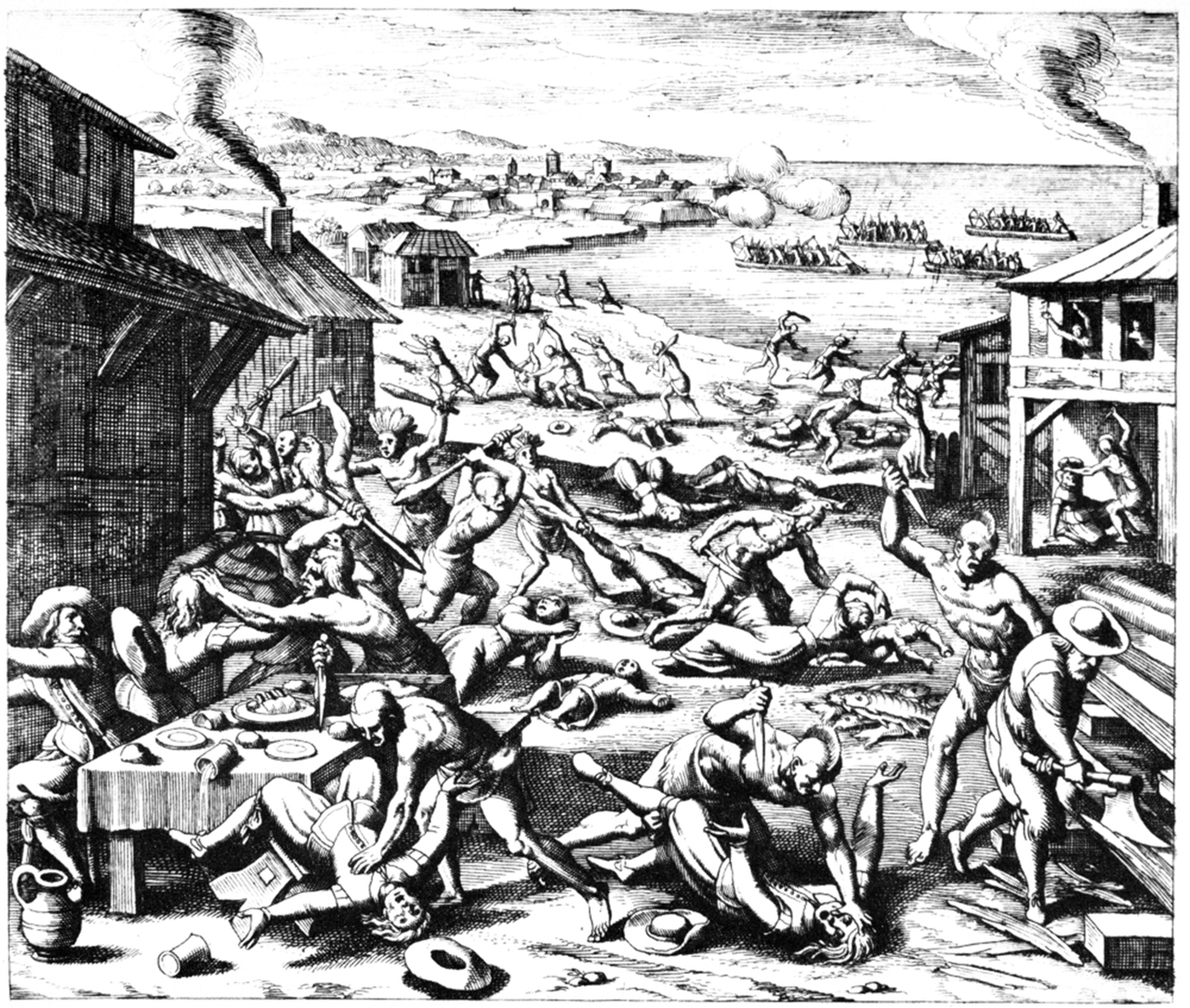

Richard Frethorne was an indentured servant working at Martin’s Hundred, a plantation a few miles from Jamestown, a year after an Indian attack in 1622 left hundreds dead in the area. A year later the royal government took over the struggling colony.

Loving and kind father and mother:

My most humble duty remembered to you, hoping in God of your good health, as I myself am at the making hereof. This is to let you understand that I your child am in a most heavy case by reason of the nature of the country, [which] is such that it causes much sickness as the scurvy and the bloody flux and diverse other diseases, which makes the body very poor and weak. And when we are sick there is nothing to comfort us; for since I came out of the ship I never ate anything but peas and loblollie [water gruel]. As for deer or venison I never saw any since I came into this land. There is indeed some fowl but we are not allowed to go and get it, but must work hard both early and late for a mess of water gruel and a mouthful of bread and beef. A mouthful of bread for a penny loaf must serve for four men which is most pitiful. People cry out day and night—Oh! that they were in England without their limbs—and would not care to lose any limb to be England again, yea, though they beg from door to door. For we live in fear of the enemy every hour, yet we have had a combat with them and we took two alive and made slaves of them. We are in great danger, for our plantation is very weak by reason of the death and sickness of our company. Our Lieutenant is dead and his father and his brother. And there was some five or six of the last year’s twenty, of which there is but three left so that we are fain to get other men to plant with us and yet we are but 32 to fight against 3000 if they should come. And the highest help that we have is ten miles of us and when the rogues overcame this place last they slew 80 persons. How then shall we do, for we lie even in their teeth?

And I have nothing to comfort me, nor there is nothing to be gotten here but sickness and death except that one had money to lay out in some things for profit. But I have nothing at all—no, not a shirt to my back nor no clothes but one poor Suit, nor but one pair of shoes, but one pair of stockings, but one cap, but two bands. My cloak is stolen by one of my own fellows, and to his dying hour [he] would not tell me what he did with it. But some of my fellows saw him have butter and beef out of a ship, which my cloak I doubt [not] paid for. So that I have not a penny to help me to either spice or sugar or strong waters, without the which one cannot live here. For as strong beer in England does fatten and strengthen them, so water here does wash and weaken these here [and] only keeps life and soul together. But I am not half a quarter so strong as I was in England and all is for want of victuals, for I do protest unto you that I have eaten more in [one] day at home than I have allowed me here for a week. You have given more than my day’s allowance to a beggar at the door and if Mr. Jackson had not relieved me, I should be in a poor case. But he like a father and she like a loving mother does still help me.

Goodman Jackson pitied me and made me a cabin to lie in always when I come up, which comforted me more than peas or water gruel. Oh, they be very godly folks and love me very well and will do anything for me. And he much marveled that you would send me [as] a servant to the Company; he said I had been better knocked on the head. And indeed so I find it now, to my great grief and misery; and say that if you love me you will redeem me suddenly, for which I do entreat and beg. And if you cannot get the merchants to redeem me for some little money, then for God’s sake get a gathering or entreat some good folks to lay out some little sum of money in meal and cheese and butter and beef. Any eating meat will yield great profit. But for God’s sake send beef and cheese and butter, or the more of one sort and none of another. But if you send cheese, it must be very old cheese; and at the cheese-monger’s you may buy very good cheese for twopence farthing or halfpenny that will be liked very well. But if you send cheese, you must have a care how you pack it in barrels and you must put cooper’s chips between every cheese or else the heat of the hold will rot them. And look whatsoever you send me—be it never so much— what[ever] I make of it, I will deal truly with you. I will send it over and beg the profit to redeem me and if I die before it come, I have entreated Goodman Jackson to send you the worth of it, who has promised he will. Good father, do not forget me but have mercy and pity my miserable case. I know if you did but see me you would weep to see me, for I have but one suit. I pray you to remember my love to all my friends and kindred. I hope all my brothers and sisters are in good health and as for my part I have set down my resolution that certainly wiII be. That is, that the answer of this letter will be life or death to me. Therefore good father, send as soon as you can and if you send me anything let this be the mark.

Moreover, on the third day of April we heard that after these rogues had gotten the pinnace and had taken all furnitures [such] as pieces [guns], swords, armor, coats of mail, powder, shot, and all the things that they had to trade withal, they killed the Captain and cut off his head. And rowing with the tail of the boat foremost, they set up a pole and put the Captain’s head upon it and so rowed home. Then the Devil set them on again so that they furnished about 200 canoes with above 1000 Indians and came. And thought to have taken the ship but she was too quick for them—which thing was very much talked of, for they always feared a ship. But now the rogues grow very bold and can use pieces, some of them, as well or better than an Englishman. For an Indian did shoot with Mr. Charles, my master’s kinsman, at a mark of white paper and he hit it at the first, but Mr. Charles could not hit it. But see the envy of these slaves, for when they could not take the ship then our men saw them threaten Accomack, that is the next plantation. And now there is no way but starving. For they had no crop last year by reason of these rogues, so that we have no corn but as ships do relieve us. Nor we shall hardly have any crop this year, and we are as like to perish first as any plantation. For we have but two hogsheads of meal left to serve us this two months; that is but a halfpenny loaf a day for a man. Is it not strange to me, think you? But what will it be when we shall go a month or two and never see a bit of bread, as my master says we must do? And he said he is not able to keep us all. Then we shall be turned up to the land and eat barks of trees or molds of the ground. Therefore with weeping tears I beg of you to help me. Oh that you did see my daily and hourly sighs, groans, and tears, and thumps that I afford mine own breast, and rue and curse the time of my birth. I thought no head had been able to hold so much water as has and does daily flow from mine eyes.

But this is certain: I never felt the want of father and mother till now. But now, dear friends, full well I know and rue it, although it were too late before I knew it.

Your loving son,

Richard Frethorne

Virginia, 3rd April, 1623

Source: Richard Frethorne, April 3, 1623, https://louis.pressbooks.pub/theamericanrevolutionprimarysourcereadings/chapter/chapter-1-2/