172 Foundation of a New Party (1855)

When President Pierce was inaugurated on the fourth of March, 1853, the pride and power of the Democratic party seemed to be at their flood. In his annual message in December following, he lauded the Compromise measures with great emphasis and declared that the repose which they had brought to the country should receive no shock during his term of office if he could avert it. In the beginning the session gave promise of a quiet one, but on the twenty-third of January the precious repose of the country to which the President had so lovingly referred in his message was rudely shocked by the proposition of Senator Douglas to repeal the Missouri compromise. The whole question of slavery was thus reopened, for the sacredness of the compact of 1820 and the wickedness of its violation depended largely upon the character of slavery itself and our constitutional relations to it.

On all sides the situation was exceedingly critical and peculiar. The Whigs, in their now practically disbanded condition, were free to act as they saw fit and were very indignant at this new demonstration in the interest of slavery, while they were yet in no mood to countenance any form of “abolitionism.” Multitudes of Democrats were equally indignant and were quite ready to join hands with the Whigs in branding slavery with the violation of its plighted faith. Both made the sacredness of the bargain of 1820 and the crime of its violation the sole basis of their hostility.

The position of the Free Soilers was radically different. They opposed slavery upon principle and irrespective of any compact or compromise. They did not demand the restoration of the Missouri compromise and although they rejoiced at the popular condemnation of the perfidy which had repealed it, they regarded it as a false issue. It was an instrument on which different tunes could be played. To restore this compromise would prevent the spread of slavery over soil that was free, but it would re-affirm the binding obligation of a compact that should never have been made and from which we were now offered a favorable opportunity of deliverance.

The situation was complicated by two other political elements. One of these was Temperance, which now for the first time had become a most absorbing political issue. The other element referred to made its appearance in the closing months of 1853 and took the name of the Know-Nothing party. It was a secret oath-bound political order and its demand was the proscription of Catholics and a probation of twenty-one years for the foreigner as a qualification for the right of suffrage. Its career was as remarkable as it was disgraceful.

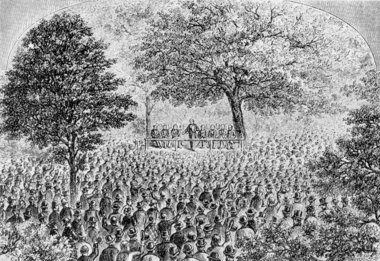

Its birth simultaneously with the repeal of the Missouri compromise was not an accident, as anyone could see who had studied the tactics of the slave-holders. It was a well-timed scheme to divide the people of the free States upon trifles and side issues, while the South remained a unit in defense of its great interest. It was the cunning attempt to balk and divert the indignation aroused by the repeal of the Missouri restriction, which else would spend its force upon the aggressions of slavery. For by thus kindling the Protestant jealousy of our people against the Pope and enlisting them in a crusade against the foreigner, the South could all the more successfully push forward its schemes. Such were the elements which mingled and commingled in the political ferment of 1854 and out of which an anti-slavery party was to be evolved capable of trying conclusions with the perfectly disciplined power of slavery. The problem was exceedingly difficult and could not be solved in a day. The necessary conditions of progress could not be slighted and the element of time must necessarily be a large one in the grand movement which was to come. The dispersion of the old parties was one thing, but the organization of their fragments into a new one on a just basis was quite a different thing. The honor of taking the first step in the formation of the Republican party belongs to Michigan, where the Whigs and Free Soilers met in State convention on the sixth of July, formed a complete fusion into one party, and adopted the name Republican. This action was followed soon after by like movements in the States of Wisconsin and Vermont. In Indiana a State “fusion”convention was held on the thirteenth of July which adopted a platform, nominated a ticket, and called the new movement the “People’s Party”. The platform, however, was narrow and equivocal and the ticket nominated had been agreed on the day before by the Know- Nothings in secret conclave, as the outside world afterward learned. The ticket was elected but it was done by combining opposite and irreconcilable elements and was not only barren of good fruits but prolific of bad ones, through its demoralizing example. For the same dishonest game was attempted the year following and was overwhelmingly defeated by the Democrats. In New York the Whigs refused to disband and the attempt to form a new party failed. The same was true of Massachusetts and Ohio. The latter State however, in 1855 fell into the Republican column and nominated Mr. Chase for Governor, who was elected by a large majority. A Republican movement was attempted this year in Massachusetts, where conservative Whiggery and Know-Nothingism blocked the way of progress, as they did also in the State of New York.

In November of the year 1854 the Know-Nothing party held a National Convention in Cincinnati, in which the hand of slavery was clearly revealed and the “Third Degree” or pro-slavery obligation of the order was adopted. And it was estimated that at least a million and a half of men afterward bound themselves by this obligation. In June of the following year another National Convention of the order was held in Philadelphia and at this convention the party was finally disrupted on the issue of slavery and its errand of mischief henceforward prosecuted by fragmentary and irregular methods. But even the Northern wing of this Order was untrustworthy on the slavery issue, having proposed, as a condition of union to limit its anti-slavery demand to the restoration of the Missouri restriction and the admission of Kansas and Nebraska as free States.

An unprecedented struggle for the Speakership [of the House] began with the opening of the Thirty-fourth Congress and lasted till the second day of February, when the free States finally achieved their first victory in the election of Banks. Northern manhood at last was at a premium and this was largely the fruit of the “border ruffian” attempts to make Kansas a slave State, which had stirred the blood of the people during the year 1855. In the meantime, the arbitrary enforcement of the Fugitive Slave Act still further contributed to the growth of an anti-slavery opinion. The famous case of Anthony Burns in Boston, the prosecution of S. M. Booth in Wisconsin and the decision of the Supreme Court of that State, the imprisonment of Passmore Williamson in Philadelphia and the outrageous rulings of Judge Kane, and the case of Margaret Gamer in Ohio all played their part in preparing the people of the free States for organized political action against the aggressions of slavery.

Near the close of the year 1855, the chairmen of the Republican State Committees of Ohio, Massachusetts, Pennsylvania, Vermont, and Wisconsin issued a call for a National Republican Convention to be held at Pittsburg on the 22nd of February, 1856, for the purpose of organizing a National Republican party and making provision for a subsequent convention to nominate candidates for President and Vice President. It was quite manifest that this was a Republican convention and not a mere aggregation of Whigs, Know-Nothings, and dissatisfied Democrats.

It contained a considerable Know-Nothing element but it made no attempt at leadership. The convention was in session two days and was singularly harmonious throughout. As chairman of the committee of organization, I had the honor to report the plan of action through which the new party took life, providing for the appointment of a National Executive Committee, the holding of a National Convention in Philadelphia on the 17th of June for the nomination of candidates for President and Vice President, and the organization of the party in counties and districts throughout the States.

The Philadelphia convention was very large and marked by unbounded enthusiasm. The spirit of liberty was up and side issues forgotten. If Know-Nothingism was present, it prudently accepted an attitude of subordination. The platform reasserted the self-evident truths of the Declaration of Independence and denied that Congress, the people of a Territory, or any other authority could give legal existence to slavery in any Territory of the United States. It asserted the sovereign power of Congress over the Territories and its right and duty to prohibit it therein. Know-Nothingism received no recognition and the double-faced issue of the restoration of the Missouri compromise was disowned, while the freedom of Kansas was dealt with as a mere incident of the conflict between liberty and slavery. On this broad platform John C. Fremont was nominated for President on the first ballot and William L. Dayton was unanimously nominated for Vice President.

Source: George W. Julian, Political Recollections, 1840-1872 (1884), 134-150. https://archive.org/details/americanhistoryt00ivunse/page/100/mode/2up