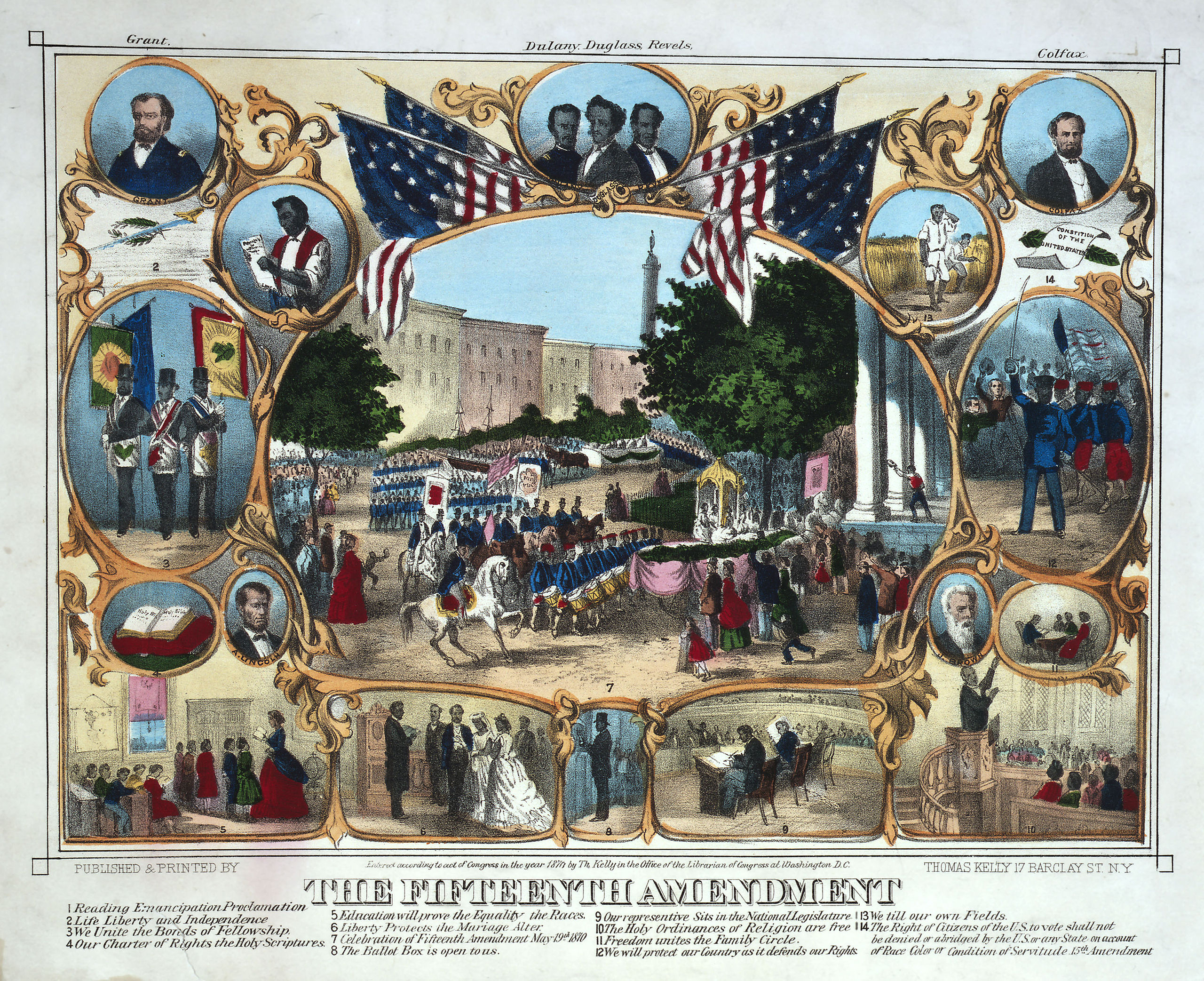

206 Fifteenth Amendment (1869)

Sir, it is now past six o’clock in the morning — a continuous session of more than eighteen hours. For more than seventeen hours the ear of the Senate has been wearied and pained with anti-republican, inhuman, and unchristian utterances, with the oft-repeated warnings, prophecies, and predictions, with petty technicalities, and carping criticisms. The majority in this Chamber, in the House, and in the country too have been arraigned, assailed, and denounced, their ideas, principles, and policies misrepresented, and their motives questioned. Sir, will our assailants never forget anything nor learn anything? Will they never see themselves as others see them? Year after year they have continuously and vehemently, as grand historic questions touching the interests of the country and the rights of our countrymen have arisen to be grappled with and solved, blurted into our unwilling ears these same warnings, prophecies, and predictions, their unreasoning prejudices and passionate declamations. Time and events, which test all things, have brought discomfiture to their cause and made their illogical and ambitious rhetoric seem to be but weak and impotent drivel.

In spite of the discomfitures of the past, the champions of slavery and of the ideas, principles, and policies pertaining to it are again doing battle for their perishing cause. Again sir, we are arraigned, again misrepresented, again denounced. Why are we again thus misrepresented, arraigned, and denounced? We the friends of human rights simply propose to submit to our countrymen an amendment of the Constitution of our country to secure the priceless boon of suffrage to citizens of the United States to whom the right to vote and be voted for is denied by the constitutions and laws of some of the States. This effort to remove the disabilities of the emancipated victims of the perished slave systems, to clothe them with power to maintain the dignity of manhood and the honor and rights of citizenship spring from our love of freedom, our sense of justice, our reverence for human nature, and our recognition of the fatherhood of God and the brotherhood of man. This effort, sanctified by patriotism, liberty, justice, and humanity is stigmatized in this Chamber as a mere partisan movement. Who make it a partisan movement? The men who are actuated by an imperative sense of duty or the men who instinctively seize the occasion to arouse the unreasoning passions of race and caste and the prejudices of ignorance and hate?

Because frivolity and fashion put their ban upon the black man, be his character ever so pure or his intelligence ever so great, statesmen in this Christian land of republican institutions must deny to him civil and political rights and privileges. Because social life has put and continues to put its brand of exclusion upon the black man, it is therefore the duty of statesmanship to maintain by class legislation the abhorrent doctrine of caste in this Christian Republic. This is the argument, the logic, the position of Senators. Honorable Senators have grown weary in reminding us that it would be a breach of our plighted faith to submit to the State Legislatures this amendment to the Constitution to secure to American citizens the right to vote and to be voted for. They tell us we were pledged by our national convention of 1868 that we were committed to the doctrine that the right to regulate the suffrage properly belonged to the loyal States.

So the earlier Republican national conventions proclaimed that slavery in the States was a local institution for which the people of each State only were responsible. But that declaration did not stand in the way of the proclamation of emancipation, did not stand in the way of the thirteenth article of the amendments of the Constitution, did not stand in the way of that series of aggressive measures by which slavery was extirpated in the States. Slavery struck at the life of the nation and the Republican party throttled its mortal foe. The Republican party in the national convention of 1868 pronounced the guarantee by Congress of equal suffrage of all loyal men at the South as demanded by every consideration of public safety, gratitude, and of justice and determined that it should be maintained. That declaration unreservedly committed the Republican party to the safety and justice of equal suffrage. The declaration that the suffrage in the loyal States properly belonged to the people of those States meant this, no more, no less: that under the Constitution it belonged to the people of each of the loyal States to regulate suffrage therein.

Senators accuse us of being actuated by partisanship, by the love of power and the hope of retaining power. Yet they never tire of reminding us that the people have in several States pronounced against equal suffrage and will do so again. I took occasion early in the debate to express the opinion that in the series of measures for the extirpation of slavery and the elevation and enfranchisement of the black race the Republican party had lost at least a quarter of a million of voters. In every great battle of the last eight years the timid, the weak faltered, fell back, or slunk away into the ranks of the enemy. Yes sir, while we have been struggling often against fearful odds, timid men, weak men, and bad men too, following the examples of timid men, weak men, and bad men in all the great struggles for the rights of human nature, have broken from our advancing ranks and fallen back to the rear or gone over to the enemy, thus giving to the foe the strength they had pledged to us. But we have gone on prospering and we shall go on prospering in spite of treacheries on the right hand and on the left. The timid may chide us, the weak reproach us, and the bad malign us. But we shall strive on, for in struggling to secure and protect the rights of others we assure our own.

Source: Henry Wilson in Appendix to the Congressional Globe, 40th Congress, 3rd session (1869), 153-154, February 8, 1869. https://archive.org/details/americanhistoryt00ivunse/page/492/mode/2up