63 Edwards Account of Revival (1743)

Northampton, Dec. 12, 1743. Ever since the great work of God that was wrought here about nine years ago, there has been a great and abiding alteration in this town in many respects. There has been vastly more religion kept up in the town, among all sorts of persons, in religious exercises and in common conversation. There has been a great alteration among the youth of the town with respect to revelry, frolicking, profane and licentious conversation, and lewd songs. And there has also been a great alteration amongst both old and young with regard to tavern-haunting. I suppose the town has been in no measure so free of vice in these respects, for any long time together, for sixty years, as it has been these nine years past. There has also been an evident alteration with respect to a charitable spirit to the poor.

Northampton, Dec. 12, 1743. Ever since the great work of God that was wrought here about nine years ago, there has been a great and abiding alteration in this town in many respects. There has been vastly more religion kept up in the town, among all sorts of persons, in religious exercises and in common conversation. There has been a great alteration among the youth of the town with respect to revelry, frolicking, profane and licentious conversation, and lewd songs. And there has also been a great alteration amongst both old and young with regard to tavern-haunting. I suppose the town has been in no measure so free of vice in these respects, for any long time together, for sixty years, as it has been these nine years past. There has also been an evident alteration with respect to a charitable spirit to the poor.

In the month of May, 1741, a sermon was preached to a company at a private house. Near the conclusion of the discourse, many of the young people and children that were professors appeared to be overcome with a sense of the greatness and glory of divine things; so that the whole room was full of nothing but outcries, faintings, and the like. About the middle of the summer I called together the young people that were communicants, from sixteen to twenty-six years of age, to my house. We had several meetings that summer of young people. It was about that time that there first began to be cryings out in the meeting-house. The months of August and September were the most remarkable of any this year for appearances of the conviction and conversion of sinners and great revivings, quickenings, and comforts of professors, and for extraordinary external effects of these things. It was a very frequent thing to see a house full of out-cries, faintings, convulsions, and such like, both with distress and also with admiration and joy. It was not the manner here to hold meetings all night, as in some places, nor was it common to continue them till very late in the night. But it was pretty often so, that there were some that were so affected and their bodies so overcome that they could not go home, but were obliged to stay all night where they were.

The preceding season had been very remarkable on this account, beyond what had been before; but this more remarkable than that. And in this season, these apparent or visible conversions (if I may so call them) were more frequently in the presence of others at religious meetings, where the appearances of what was wrought on the heart fell under public observation.

In the month of March, I led the people into a solemn public renewal of their covenant with God. To that end, having made a draft of a covenant, I first proposed it to some of the principal men in the church. Then to the people, in their several religious associations in various parts of the town. Then to the whole congregation in public. And then I deposited a copy of it in the hands of each of the four deacons, that all who desired it might resort to them and have opportunity to view and consider it. Then the people in general that were above fourteen years of age first subscribed the covenant with their hands and then, on a day of fasting and prayer, all together presented themselves before the Lord in his house and stood up and solemnly manifested their consent to it, as their vow to God.

In the beginning of the summer of 1742, there seemed to be an abatement of the liveliness of people’s affections in religion; but yet many were often in a great height of them. And in the fall and winter following, there were at times extraordinary appearances. But in the general, people’s engagedness in religion and the liveliness of their affections have been on the decline. And some of the young people especially have shamefully lost their liveliness and vigor in religion and much of the seriousness and solemnity of their spirits. But there are many that walk as becomes saints and to this day there are a considerable number in town that seem to be near to God, and maintain much of the life of religion, and enjoy many of the sensible tokens and fruits of his gracious presence.

The effects and consequences of things among us plainly show the following things, viz. that the degree of grace is by no means to be judged by the degree of joy or the degree of zeal. And that indeed we cannot at all determine by these things who are gracious and who are not. And that it is not the degree of religious affections but the nature of them that is chiefly to be looked at. Some that have had very great raptures of joy and have been extraordinarily filled (as the vulgar phrase is) and have had their bodies overcome, and that very often, have manifested far less of the temper of Christians in their conduct since than some others that have been still and have made no great outward show. But then again, there are many others that have had extraordinary joys and emotions of mind with frequent great effects upon their bodies, that behave themselves steadfastly as humble, amiable, eminent Christians.

‘Tis evident that there may be great religious affections in individuals which may in show and appearance resemble gracious affections and have the same effects upon their bodies, but are far from having the same effect on the temper of their minds and the course of their lives. And likewise there is nothing more manifest, by what appears amongst us, than that the good estate of individuals is not chiefly to be judged of by any exactness of steps and method of experiences in what is supposed to be the first conversion. But that we must judge by the spirit that breathes, the effect wrought upon the temper of the soul in the time of the work and remaining afterwards. Though there have been very few instances amongst us of what is ordinarily called scandalous sins, known to me; yet the temper that some of them show and the behavior they have been of, together with some things in the nature and circumstances of their experiences, make me much afraid lest there be a considerable number that have woefully deceived themselves. Though on the other hand, there is a great number whose temper and conversation is such as justly confirms the charity of others towards them and not a few in whose disposition and walk there are amiable appearances of eminent grace. And notwithstanding all the corrupt mixtures that have been in the late work here, there are not only many blessed fruits of it in particular persons that yet remain, but some good effects of it upon the town in general.

A spirit of party has more extensively subsided. I suppose there has been less appearance these three or four years past of that division of the town into two parties which has long been our bane, than has been at any time during the preceding thirty years. And the people have apparently had much more caution and a greater guard on their spirit and their tongues, to avoid contention and unchristian hearts in town-meetings and on other occasions. And ’tis a thing greatly to be rejoiced in that the people very lately came to an agreement and final issue with respect to their grand controversy relating to their common lands. Which has been above any other particular thing, a source of mutual prejudices, jealousies, and debates for fifteen or sixteen years past. The people also seem to be much more sensible of the danger of resting in old experiences or what they were subjects of at their supposed first conversion, and to be more fully convinced of the necessity of forgetting the things that are behind and pressing forward and maintaining earnest labor, watchfulness, and prayerfulness, as long as they live.

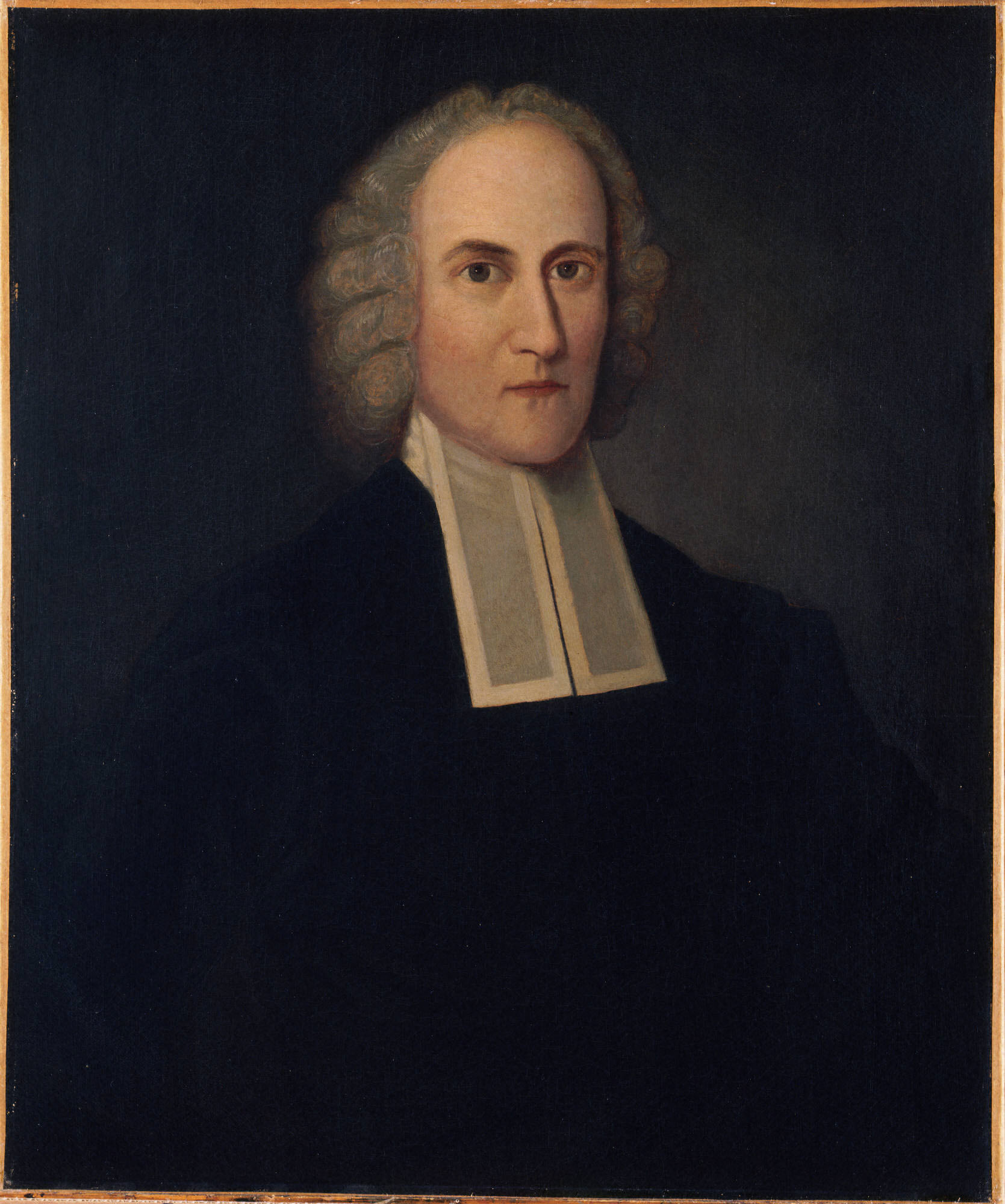

I am, Rev. Sir, Your friend and brother, Jonathan Edwards.

Source: “An Account of Revival”, by Jonathan Edwards in a letter to the Rev. Thomas Prince of Boston, evidently intended for publication, entitled “The State of Religion at Northampton in the County of Hampshire, About 100 Miles Westward of Boston”. It was published in The Christian History, I, Jan. 14, 21, 28, 1743).