43 Dutchmen in Boston (1680)

Dutch travelers Danckaerts and Sluyter also visited Boston and recorded their observations about what they saw there as well. In addition to visiting Harvard College, they met John Eliot and traveled to some of Boston’s suburbs.

24th, Monday. We walked with our captain into the town, for his house stood a little one side of it and the first house he took us to was a tavern. From there he conducted us to the governor, who dwelt in only a common house, and that not the most costly. He is an old man, quiet and grave. He was dressed in black silk, but not sumptuously. The governor inquired who we were and where from and where we going. He then presented us a small cup of wine and with that we finished.

7th, Sunday. We heard preaching in three churches by persons who seemed to possess zeal but no just knowledge of Christianity. The auditors were very worldly and inattentive. The best of the ministers whom we have yet heard is a very old man named John Eliot, who has charge of the instruction of the Indians in the Christian religion.

8th, Monday. We went about eight o’clock in the morning to Roxbury, which is three-quarters of an hour from the city. We found it justly called Rocksbury for it was very rocky and had hills entirely of rocks. Returning to his house we spoke to him [Mr. Eliot], and he received us politely. Although he could speak neither Dutch nor French and we spoke but little English and were unable to express ourselves in it always, we managed by means of Latin and English to understand each other. He was seventy-seven years old and had been forty-eight years in these parts. He had learned very well the language of the Indians who lived about there. We asked him for an Indian Bible. He said in the late Indian war, all the Bibles and Testaments were carried away and burnt or destroyed so that he had not been able to save any for himself. We presented him our Declaration in Latin and informed him about the persons and conditions of the church, whose declaration it was. With which he was delighted and could not restrain himself from praising God that had raised up men and reformers and begun the reformation in Holland. He deplored the decline of the church in New England and especially in Boston, so that he did not know what would be the final result.

9th, Tuesday. We started out to go to Cambridge, lying to the northeast of Boston, in order to see their college [Harvard] and printing office. We reached Cambridge about eight o’clock. It is not a large village and the houses stand very much apart. The college building is the most conspicuous among them. We went to it, expecting to see something curious as it is the only college or would-be academy of the Protestants in all America, but we found ourselves mistaken. We found there eight or ten young fellows sitting around smoking tobacco, with the smoke of which the room was so full that you could hardly see. And the whole house smelt so strong of it that when I was going up stairs I said, this is certainly a tavern. We excused ourselves that we could speak English only a little, but understood Dutch or French, which they did not. However, we spoke as well as we could. We inquired how many professors there were and they replied not one, that there was no money to support one. We asked how many students there were. They said at first thirty and then came down to twenty. I afterwards understood there are probably not ten. They could hardly speak a word of Latin, so that my comrade could not converse with them. They took us to the library where there was nothing particular. We looked over it a little. They presented us with a glass of wine. This is all we ascertained there. The minister of the place goes there morning and evening to make prayer and has charge over them. The students have tutors or masters. Our visit was soon over and we left them to go and look at the land about there.

We found the place beautifully situated on a large plain more than eight miles square with a fine stream in the middle of it, capable of bearing heavily laden vessels. We passed by the printing office, but there was nobody in it. We looked in and saw two presses with six or eight cases of type. There is not much work done there. We went back to Charlestown where, after waiting a little, we crossed over about three o’clock. We inquired how long our departure would be delayed and as we understood him, it would be the last of the coming week. That was annoying to us. Indeed we have found the English the same everywhere, doing nothing but lying and cheating, when it serves their interest.

12th, Friday, We went in the afternoon to Mr. John Taylor’s, to ascertain whether he had any good wine and to purchase some for our voyage and also some brandy. On arriving at his house, we found him a little cool; indeed, not as he was formerly. We also inquired how we could obtain the history and laws of this place. At last it came out. He said we must be pleased to excuse him if he did not give us admission to his house. He durst not do it in consequence of there being a certain evil report in the city concerning us. They had been to warn him not to have too much communication with us, if he wished to avoid censure. They said we certainly were Jesuits [they were actually Labadists, part of a communistic Protestant movement] who had come here for no good. For we were quiet and modest and an entirely different sort of people from themselves. That we could speak several languages, were cunning and subtle of mind and judgment, had come there without carrying on any traffic or any other business except only to see the place and country. This suspicion seemed to have gained more strength because the fire at Boston over a year ago was caused by a Frenchman. Although he had been arrested, they could not prove it against him. But in the course of the investigation they discovered he had been counterfeiting coin, which was a crime as infamous as the other. He was condemned, both of his ears were cut off, and he was ordered to leave the country.

23rd, Thursday. They are all Independents in matters of religion, if it can be called religion. They baptize no children except those of the members of the congregation. All their religion consists in observing Sunday by not working or going into the taverns on that day. No stranger or traveler can therefore be entertained on a Sunday, which begins at sunset on Saturday and continues until the same time on Sunday. At these two hours you see all their countenances change. Saturday evening the constable goes round into all the taverns of the city for the purpose of stopping all noise and debauchery, which frequently causes him to stop his search before his search causes the debauchery to stop. There is a penalty for cursing and swearing such as they please to impose, the witnesses thereof being at liberty to insist upon it. Nevertheless, you discover little difference between this and other places. Drinking and fighting occur there not less than elsewhere; and as to truth and true godliness, you must not expect more of them than of others. When we were there, four ministers’ sons were learning the silversmith’s trade.

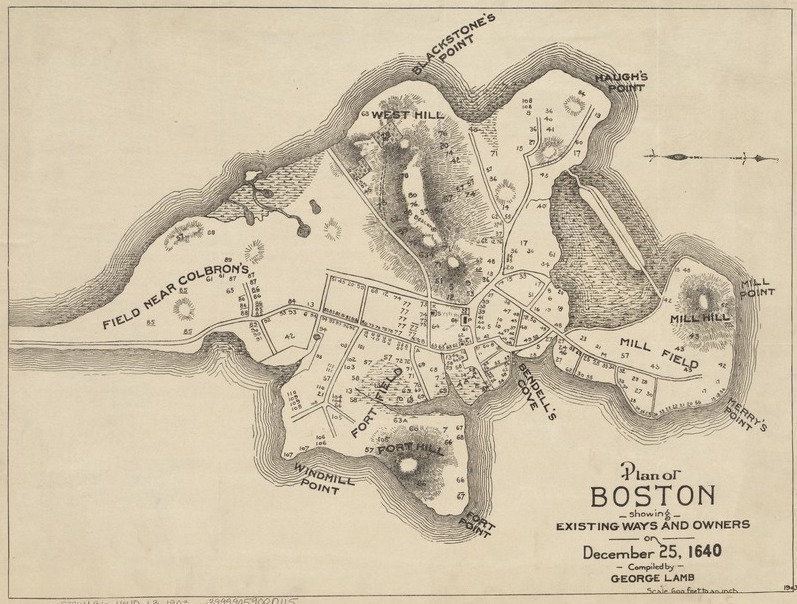

As to Boston particularly, it lies in latitude 42° 20′ on a very fine bay. The city is quite large. It has three churches or meeting houses as they call them. All the houses are made of thin, small cedar shingles, nailed against frames and then filled in with brick and other stuff. For this reason these towns are so liable to fires, as have already happened several times. And the wonder to me is that the whole city has not been burnt down, so light and dry are the materials. There is a large dock in front of it constructed of wooden piers where the large ships go to be careened and rigged. The smaller vessels all come up to the city. On the left hand side across the river lies Charlestown, a considerable place where there is some shipping. Upon the point of the bay on the left hand there is a block-house along which a piece of water runs, called the Milk ditch. The whole place has been an island, but it is now joined to the mainland by a low road to Roxbury. In front of the town there are many small islands, between which you pass in sailing in and out.

Source: Two Dutchmen in Boston (1680), by Jaspar Dankers and Peter Sluyter (Translated by Henry C. Murphy, 1867), in Journal of a Voyage to New York in 1679-80, in Long Island Historical Society, Memoirs (Brooklyn, 1867), I, 377-395. https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.45493/page/n515/mode/2up