128 Discussion of Peace (1814-15)

December 12, 1814.

December 12, 1814.

Lord Gambier [Admiral in the Royal Navy] said that they did not consider the fisheries within their jurisdiction as rights, but merely as privileges granted.

Dr. Adams [William Adams, a British Admiralty lawyer] said that it would be very easy to draw a proviso by which it should be agreed to negotiate upon the two subjects and yet without implying an abandonment on the part of the United States of their claim.

I said if he thought it so easy, I would thank him to undertake it. I did not believe it possible. We had drawn up and now proposed a general article founded on a precedent in the Treaty of 1794, engaging to negotiate upon all the subjects of difference unadjusted which would include those of the Mississippi navigation and the fisheries within the British jurisdiction.

They read our article and immediately rejected it, finding the word commerce in it. Mr. Gallatin [Albert Gallatin, U.S. Secretary of the Treasury] proposed to leave that word out.

Adams and Goulburn [Henry Goulburn, Secretary of the Colonial Office] still rejected the article. Adams still said we might draw a proviso reserving our construction of the Treaty of 1783 and agreeing to negotiate on the two subjects, and added that he mentioned it because he believed that if the other question about the islands could be got rid of, the British Government would be disposed to some accommodation upon this.

Mr. Bayard [James A. Bayard Sr., Delaware Federalist Senator] drew a proviso for the purpose and handed it over the table. They read it and Lord Gambier immediately said “I, for one, can never agree to that.” Mr. Bayard asked what the object of the article as proposed by the British Plenipotentiaries was. Adams and Goulburn said it was sent to them from England. They were not to account for the motive of their Government in proposing that or any other article. Mr. Bayard said he did not ask them for the motive of their Government but for the object of the article. He supposed gentlemen would at least be authorized to explain that.

Dr. Adams said they had sent us the article as they had received it and we must construe it for ourselves. He had only said (and it was merely his individual opinion, he would not wish to be understood as pledging the opinion of his Government or even of his colleagues) he thought we might easily agree to an article with a proviso reserving our claim to the right by the Treaty of 1783.

We had sent them three alternatives for their last paragraph of the eighth article. One of these alternatives had been adopted in England and sent back to them, modified into this article. We had offered them the navigation of the Mississippi clogged with conditions which would render it of no effect, confining their access to a single point and upon a payment of full duties upon merchandise intended merely to pass through our territories for exportation.

Mr. Gallatin said that had not been our intention. The access would be given sufficient for all the purposes of transporting the merchandise and by our laws a drawback from the duties was allowed upon the exportation of goods. The benefit of which would be allowed, of course, to the merchandise only passing through for exportation. “But surely,” said he, “you could not expect to introduce into the United States your goods and merchandise duty free.” “And,” said Mr. Clay, “as you had drawn the first paragraph, you might have gone from Quebec through any part of our territories.”

Mr. Goulburn said “No, that was not their intention.”

Mr. Gallatin then took the Mississippi and fisheries article, proposed some alterations to it and said that we labored under great inconvenience and disadvantage in the negotiation. We had no opportunity of communicating with our Government and were continually obliged to take responsibility upon ourselves, while they referred to their Government for every detail.

22nd. As soon as I came into my chamber, Mr. Gallatin brought me the British note. It agrees to be silent upon the navigation of the Mississippi and the fisheries and to strike out the whole of the eighth article. Mr. Clay soon after came into my chamber and on reading the British note, manifested some chagrin. He still talked of breaking off the negotiation but he did not exactly disclose the motive of his ill humor, which was however easily seen through. He would have much preferred the proposed eighth article with the proposed British paragraph, formally admitting that the British right to navigate the Mississippi and the American right to the fisheries within British jurisdiction were both abrogated by the war. I think his conversation with Lord Gambier on the subject last week at their dinner, the day before we sent our note, had the tendency to induce the British to adhere to their paragraph, and that Clay is disappointed at their having given it up. And he has so entire an ascendency over Mr. Russell [Jonathan Russell, Massachusetts-born U.S. diplomat], though a New England man and claiming to be a Massachusetts man, that Russell repeatedly told me last week when I assured him that I would not sign the treaty with an article admitting that our right to any part of the fisheries was forfeited, that he should be sorry to sign a treaty without me but that he did not think that part of the fisheries an object for which the war should be continued. That he was for insisting upon it as long as possible but for giving it up at last, if the British would not sign without it.

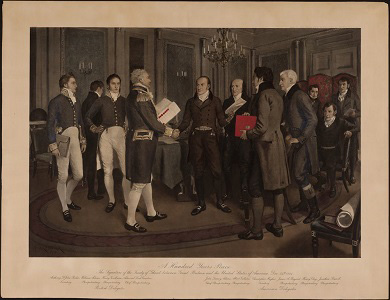

24th. A few mistakes in the copies were rectified and then the six copies were signed and sealed by the three British and the five American Plenipotentiaries. Lord Gambier delivered to me the three British copies and I delivered to him the three American copies of the treaty, which he said he hoped would be permanent. And I told him I hoped it would be the last treaty of peace between Great Britain and the United States. We left them at half-past six o’clock.

25th. Christmas-day. The day of all others in the year most congenial to proclaiming peace on earth and good will to men. We received shortly after dinner a note from the Intendant informing us that he had just received an official communication of the conclusion of the peace and inviting us to dine with him on Wednesday next, to celebrate the event.

27th. Mr. Gallatin had suggested that we ought to make to the British Government an official communication of our full power to negotiate a treaty of commerce. The proposition was now renewed and after some discussion it was agreed that Mr. Gallatin should make a draft of a note for that purpose.

28th. Lord Gambier told me that he heard we were to send them a note proposing the negotiation of a treaty of commerce. Mr. Clay had met this morning Mr. Goulburn and Dr. Adams and given them the information. Dr. Adams said that their powers were expired and he doubted whether they could even receive the note.

January 5, 1815. Another important question arose, how we were to dress for the banquet of this day. To settle it Mr. Smith at my request called upon Mr. Goulburn and enquired how he proposed to go. He answered in uniform and we accordingly all went in uniform. The banquet was at the Hotel de Ville and was given by subscription by the principal gentlemen of the city. We sat down to table about five o’clock in the largest hall of the building, fitted up for the occasion with white cotton hangings. The American and British flags were intertwined together under olive-trees at the head of the hall. Mr. Goulburn and myself were seated between the Intendant and the Mayor at the center of the cross-piece of the table. There were about ninety persons seated at the table.

As we went into the hall, Hail Columbia was performed by the band of music. It was followed by God save the King and these two airs were alternately repeated during the dinner-time until Mr. Goulburn thought they became tiresome. I was of the same opinion. The Intendant and the Mayor alternately toasted “His Britannic Majesty”, and “the United States”, “the Allied Powers”, and “the Sovereign Prince”, “the Negotiators”, and “the Peace.” I then remarked to Mr. Goulburn that he must give the next toast, which he did. It was “the Intendant and the Mayor; the City of Ghent, its prosperity; and our gratitude for their hospitality and the many acts of kindness that we had received from them.” I gave the next and last toast, which was “Ghent, the city of peace; may the gates of the temple of Janus, here closed, not be opened again for a century!”

John Quincy Adams, Memoirs (edited by Charles Francis Adams, 1874), III, 109-139. https://archive.org/details/toldcontemporari03hartrich/page/426/mode/2up