141 Chicago (1833)

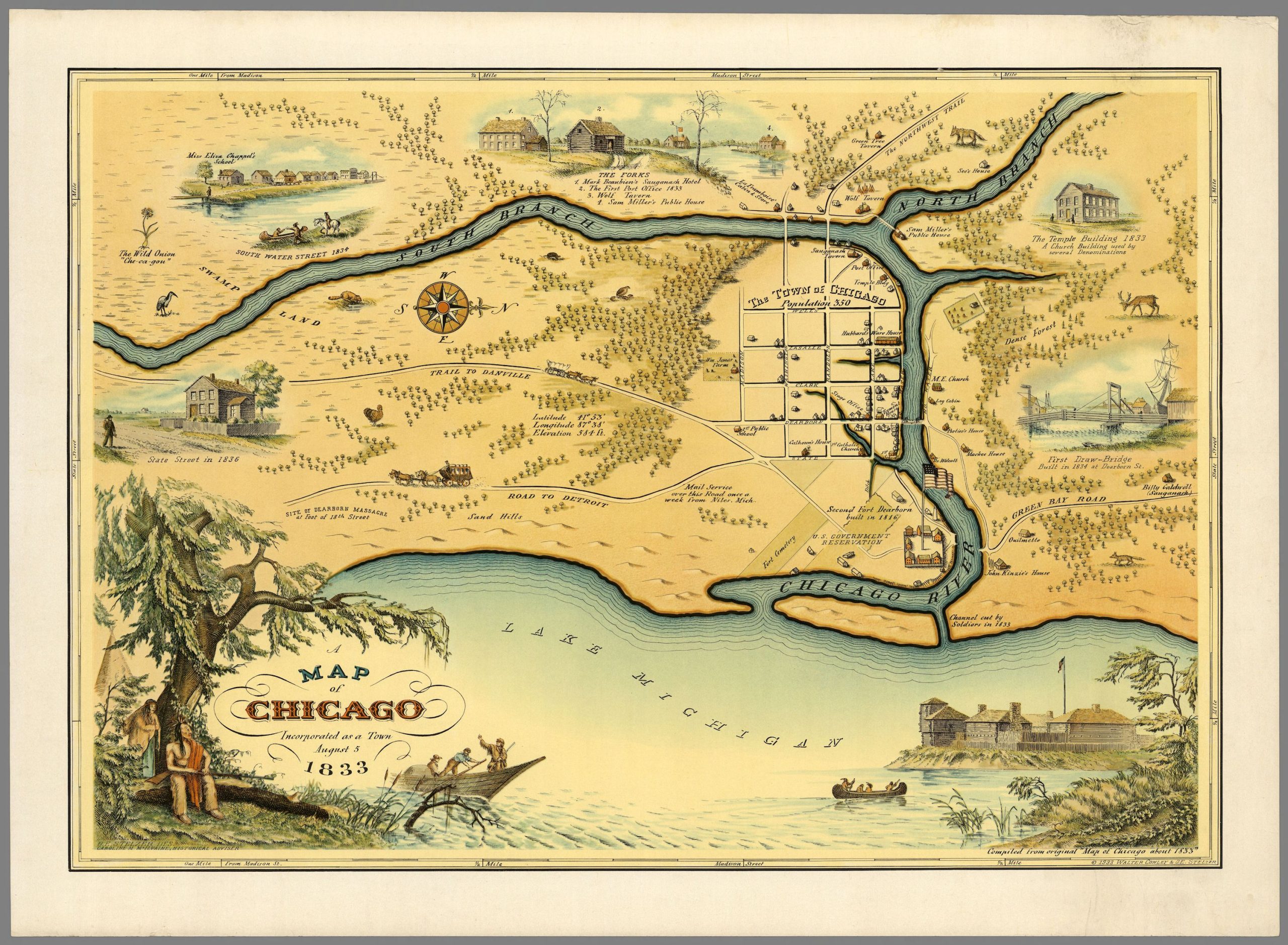

Chicago is situated on Lake Michigan at the confluence of Chicago River, a small stream affording the advantages of a canal to the inhabitants for a limited distance. At the mouth of the river is Fort Dearborn, garrisoned by a few soldiers and one of the places which has been long held to keep the Indian tribes in awe. The entrance from the lake to the river is much obstructed by sand banks and an attempt is making to improve the navigation.

Chicago consists of about 150 wood houses, placed irregularly on both sides of the river, over which there is a bridge. This is already a place of considerable trade, supplying salt, tea, coffee, sugar, and clothing to a large tract of country to the south and west and when connected with the navigable point of the River Illinois by a canal or railway, cannot fail of rising to importance. Almost every person I met regarded Chicago as the germ of an immense city and speculators have already bought up, at high prices, all the building ground in the neighborhood. Chicago will in all probability attain considerable size, but its situation is not so favorable to growth as many other places in the Union. The country south and west of Chicago has a channel of trade to the south by New Orleans and the navigation from Buffalo by Lake Huron is of such length that perhaps the produce of the country to the south of Chicago will find an outlet to Lake Erie by the waters of the rivers Wabash and Mamee. A canal has been in progress for three years connecting the Wabash and Mamee, which flows into the west end of Lake Erie. And there can be little difficulty in connecting the Wabash with the Illinois which, if effected, will materially check the rise of Chicago.

At the time of visiting Chicago there was a treaty in progress with the Pottowatamy Indians and it was supposed nearly 8000 Indians of all ages, belonging to different tribes, were assembled on the occasion. A treaty being considered a kind of general merrymaking which lasts several weeks and animal food on the present occasion was served out by the States government. The forests and prairies in the neighborhood were studded with the tents of the Indians and numerous herds of horses were browsing in all directions. Some of the tribes could be distinguished by their peculiarities. The Sauks and Foxes have their heads shaven with exception of a small tuft of hair on the crown. Their garments seemed to vary according to their circumstances and not to their tribes. The dress of the squaws was generally blue cloth and sometimes printed cotton with ornaments in the ears and occasionally also in the nose. The men generally wore white blankets with a piece of blue cloth round their loins and the poorest of them had no other covering, their arms, legs, and feet being exposed in nakedness. A few of them had cotton trousers and jackets of rich patterns, loosely flowing, secured with a sash; boots and handkerchiefs or bands of cotton with feathers in the head-dress, their appearance reminding me of the costume of some Asiatic nations. The men are generally without beards but in one or two instances I saw tufts of hair on the chin which seemed to be kept with care, and this was conspicuously so amongst the well-dressed portion. The countenances of both sexes were frequently bedaubed with paint of different kinds, including red, blue, and white.

In the forenoon of my arrival, a council had been held without transacting business and a race took place in the afternoon. The spectators were Indians with exception of a few travelers, and their small number showed the affair excited little interest. The riders had a piece of blue cloth round their loins and in other respects were perfectly naked, having the whole of their bodies painted of different hues. The racehorses had not undergone a course of training. They were of ordinary breed and according to British taste at least, small, coarse, and ill-formed. Intoxication prevailed to a great extent amongst both sexes. When under the influence of liquor, they did not seem unusually loquacious and their chief delight consisted in venting low shouts resembling something between the mewing of a cat and the barking of a dog. I observed a powerful Indian stupefied with spirits attempting to gain admittance to a shop, vociferating in a noisy manner. As soon as he reached the highest step, a white man gave him a push and he fell with violence on his back in a pool of mud. He repeated his attempt five or six times in my sight and was uniformly thrown back in the same manner. Male and female Indians were looking on and enjoying the sufferings of their countryman. The inhuman wretch who thus tortured the poor Indian was the vender of the poison which had deprived him of his senses.

Besides the assemblage of Indians there seemed to be a general fair at Chicago. Large wagons drawn by six or eight oxen and heavily laden with merchandise were arriving from and departing to distant parts of the country. There was also a kind of horse market and I had much conversation with a dealer from the State of New York, having serious intentions of purchasing a horse to carry me to the banks of the Mississippi, if one could have been got suitable for the journey. The dealers attempted to palm colts on me for aged horses and seemed versed in all the trickery which is practiced by their profession in Britain.

A person showed me a model of a thrashing machine and a churn for which he was taking orders and said he furnished the former at $30 or £6, 10 S. sterling. There were a number of French descendants who are engaged in the fur trade, met in Chicago for the purpose of settling accounts with the Indians. They were dressed in broadcloths and boots and boarded in the hotels. They are a swarthy scowling race, evidently tinged with Indian blood, speaking the French and English languages fluently and much addicted to swearing and whisky.

The hotel at which our party was set down was so disagreeably crowded that the landlord could not positively promise beds, although he would do everything in his power to accommodate us. The house was dirty in the extreme and confusion reigned throughout, which the extraordinary circumstances of the village went far to extenuate. I contrived however to get on pretty well, having by this time learned to serve myself in many things, carrying water for washing, drying my shirt, wetted by the rain of the preceding evening, and brushing my shoes. The table was amply stored with substantial provisions to which justice was done by the guests, although indifferently cooked and still more so served up.

When bedtime arrived, the landlord showed me to an apartment about ten feet square in which there were two small beds already occupied, assigning me in a comer a dirty pallet which had evidently been recently used and was lying in a state of confusion. Undressing for the night had become a simple proceeding and consisted in throwing off shoes, neck-cloth, coat, and vest, the two latter being invariably used to aid the pillow, and I had long dispensed with a nightcap. I was awoke from a sound sleep towards morning by an angry voice uttering horrid imprecations accompanied by a demand for the bed I occupied. A lighted candle which the individual held in his hand showed him to be a French trader accompanied by a friend. And as I looked on them for some time in silence, their audacity and brutality of speech increased. At length I lifted my head from the pillow, leant on my elbow and with a steady gaze and the calmest tone of voice said, “Who are you that address me in such language?” The countenance of the angry individual fell and he subduedly asked to share my bed. Wishing to put him to a farther trial, I again replied, “If you will ask the favor in a proper manner, I shall give you an answer.” He was now either ashamed of himself or felt his pride hurt and both left the room without uttering a word. Next morning, the individuals who slept in the apartment with me discovered that the intruders had acted most improperly towards them and the most noisy of the two entered familiarly into conversation with me during breakfast, without alluding to the occurrence of the preceding evening.

Source: Patrick Shirreff, A Tour through North America (1835) https://archive.org/details/toldcontemporari03hartrich/page/474/mode/2up