72 Character of the Indians (1767)

The character of the Indians, like that of other uncivilized nations, is composed of a mixture of ferocity and gentleness. They are at once guided by passions and appetites which they hold in common with the fiercest beasts that inhabit their woods and are possessed of virtues which do honor to human nature. In the following estimate I shall endeavor to forget on the one hand the prejudices of Europeans, who usually annex to the word Indian epithets that are disgraceful to human nature and who view them in no other light than as savages and cannibals. Whilst with equal care I avoid any partiality towards them, as some must naturally arise from the favorable reception I met with during my stay among them.

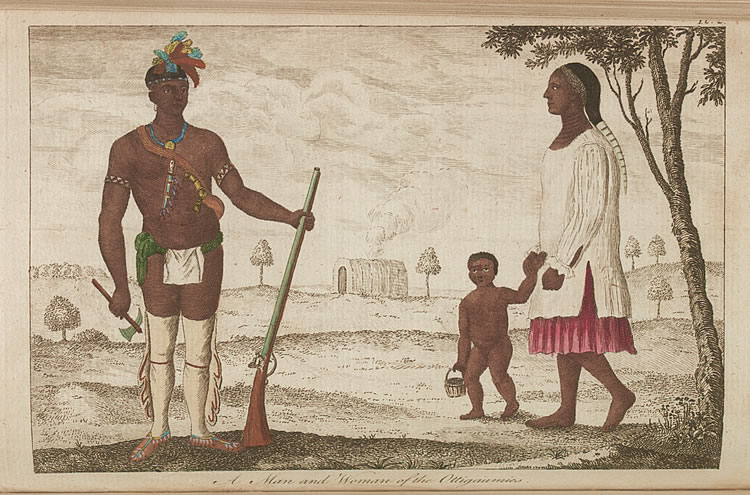

At the same time I shall confine my remarks to the nations inhabiting only the western regions such as the Naudowessies, the Ottagaumies, the Chipeways, the Winnebagoes, and the Saukies. For as throughout that diversity of climates the extensive continent of America is composed of, there are people of different dispositions and various characters, it would be incompatible with my present undertaking to treat of all these and to give a general view of them as a conjunctive body.

That the Indians are of a cruel, revengeful, inexorable disposition; that they will watch whole days unmindful of the calls of nature and make their way through pathless and almost unbounded woods, subsisting only on the scanty produce of them, to pursue and revenge themselves of an enemy; that they hear unmoved the piercing cries of such as unhappily fall into their hands and receive a diabolical pleasure from the tortures they inflict on their prisoners, I readily grant. But let us look on the reverse of this terrifying picture and we shall find them temperate both in their diet and potations [drink] (it must be remembered that I speak of those tribes who have little communication with Europeans); that they withstand with unexampled patience the attacks of hunger or the inclemency of the seasons and esteem the gratification of their appetites but as a secondary consideration. We shall likewise see them sociable and humane to those whom they consider as their friends and even to their adopted enemies, and ready to partake with them of the last morsel or to risk their lives in their defense.

In contradiction to the report of many other travelers, all of which have been tinctured with prejudice, I can assert that notwithstanding the apparent indifference with which an Indian meets his wife and children after a long absence, an indifference proceeding rather from custom than insensibility, he is not unmindful of the claims either of connubial or parental tenderness. The little story I have introduced in the preceding chapter of the Naudowessie woman lamenting her child and the immature death of the father will elucidate this point and enforce the assertion much better than the most studied arguments I can make use of.

Accustomed from their youth to innumerable hardships, they soon become superior to a sense of danger or the dread of death. And their fortitude, implanted by nature and nurtured by example, by precept, and accident never experiences a moment’s allay. Though slothful and inactive whilst their store of provision remains unexhausted and their foes are at a distance, they are indefatigable and persevering in pursuit of their game or in circumventing their enemies.

If they are artful and designing and ready to take every advantage, if they are cool and deliberate in their councils and cautious in the extreme either of discovering their sentiments or of revealing a secret, they might at the same time boast of possessing qualifications of a more animated nature: of the sagacity of a hound, the penetrating sight of a lynx, the cunning of the fox, the agility of a bounding roe, and the unconquerable fierceness of the tiger.

In their public characters, as forming part of a community, they possess an attachment for that band to which they belong unknown to the inhabitants of any other country. They combine as if they were actuated only by one soul against the enemies of their nation and banish from their minds every consideration opposed to this. They consult without unnecessary opposition or without giving way to the excitements of envy or ambition on the measures necessary to be pursued for the destruction of those who have drawn on themselves their displeasure. No selfish views ever influence their advice or obstruct their consultations. Nor is it in the power of bribes or threats to diminish the love they bear their country.

The honor of their tribe and the welfare of their nation is the first and most predominant emotion of their hearts and from hence proceed in a great measure all their virtues and their vices. Actuated by this, they brave every danger, endure the most exquisite torments, and expire triumphing in their fortitude not as a personal qualification but as a national characteristic. From thence also flow that insatiable revenge towards those with whom they are at war and all the consequent horrors that disgrace their name. Their uncultivated minds being incapable of judging of the propriety of an action, in opposition to their passions which are totally insensible to the controls of reason or humanity, they know not how to keep their fury within any bounds. And consequently that courage and resolution which would otherwise do them honor degenerates into a savage ferocity.

But this short dissertation must suffice; the limits of my work will not permit me to treat the subject more copiously or to pursue it with a logical regularity. The observations already made by my readers on the preceding pages will I trust render it unnecessary, as by them they will be enabled to form a tolerably just idea of the people I have been describing. Experience teaches that anecdotes and relations of particular events, however trifling they might appear, enable us to form a truer judgment of the manners and customs of a people and are much more declaratory of their real state than the most studied and elaborate disquisition without these aids.

Source: Jonathan Carver, Travels through the Interior Parts of North-America in the Years 1766, 1767, and 1768 (1778), 408-414. https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.45494/page/n357/mode/2up