130 Argument for Internal Improvements (1817)

At peace with all the world, abounding in pecuniary means, and what was of the most importance and at what he rejoiced as most favorable to the country, party and sectional feelings immerged [merged] in a liberal and enlightened regard to the general concerns of the nation — such said he are the favorable circumstances under which we are now deliberating. Thus situated, to what can we direct our resources and attention more important than internal improvements? What can add more to the wealth, the strength, and the political prosperity of our country? It gives to the interior the advantages possessed by the parts most eligibly situated for trade. It makes the country price, whether in the sale of the raw product or in the purchase of the articles for consumption, approximate to that of the commercial towns. In fact if we look into the nature of wealth we will find that nothing can be more favorable to its growth than good roads and canals. An article to command a price must not only be useful but must be the subject of demand, and the better the means of commercial intercourse the larger is the sphere of demand.

But said Mr. C, there are higher and more powerful considerations why Congress ought to take charge of this subject. If we were only to consider the pecuniary advantages of a good system of roads and canals, it might indeed admit of some doubt whether they ought not to be left wholly to individual exertions. But when we come to consider how intimately the strength and political prosperity of the Republic are connected with this subject, we find the most urgent reasons why we should apply our resources to them. We occupy a Surface prodigiously great in proportion to our numbers. The common strength is brought to bear with great difficulty on the point that may be menaced by an enemy. It is our duty then, as far as in the nature of things it can be effected, to counteract this weakness. Good roads and canals judiciously laid out are the proper remedy. In the recent war, how much did we suffer for the want of them! Besides the tardiness and the consequential inefficacy of our military movements, to what an increased expense was the country put for the article of transportation alone! In the event of another war, the saving in this particular would go far towards indemnifying us for the expense of constructing the means of transportation.

But on this subject of national power, what can be more important than a perfect unity in every part, in feelings and sentiments? And what can tend more powerfully to produce it, than overcoming the effects of distance? No country enjoying freedom ever occupied anything like as great an extent of country as this Republic. We are great and rapidly — he was about to say fearfully — growing. This is our pride and danger — our weakness and our strength. Little does he deserve to be entrusted with the liberties of this people, who does not raise his mind to these truths. We are under the most imperious obligation to counteract every tendency to disunion. The strongest of all cements is undoubtedly, the wisdom, justice, and above all the moderation of this House. Yet the great subject on which we are now deliberating, in this respect deserves the most serious consideration. Whatever impedes the intercourse of the extremes with this, the center of the Republic, weakens the Union. The more enlarged the sphere of commercial circulation, the more extended that of social intercourse. The more strongly are we bound together, the more inseparable are our destinies.

Those who understand the human heart best, know how powerfully distance tends to break the sympathies of our nature. Nothing, not even dissimilarity of language, tends more to estrange man from man. Let us then bind the Republic together with a perfect system of roads and canals. Let us conquer space. It is thus the most distant parts of the Republic will be brought within a few days travel of the center. It is thus that a citizen of the West will read the news of Boston still moist from the press. The mail and the press are the nerves of the body politic. By them the slightest impression made on the most remote parts is communicated to the whole system. And the more perfect the means of transportation, the more rapid and true the vibration.

He understood there were, with some members, Constitutional objections. It was mainly urged that the Congress can only apply the public money in execution of the enumerated powers. He was no advocate for refined arguments on the Constitution. The instrument was not intended as a thesis for the logician to exercise his ingenuity on. It ought to be construed with plain, good sense. And what can be more express than the Constitution on this very point? The first power delegated to Congress is comprised in these words: “To lay and collect taxes, duties, imposts, and excises; to pay the debts and provide for the common defense and general welfare of the United States. But all duties, imposts, and excises shall be uniform throughout the United States.” First the power is given to lay taxes. Next the objects are enumerated to which the money accruing from the exercise of this power may be applied: to pay the debts, provide for the common defense, and promote the general welfare. And last the rule for laying the taxes is prescribed: that all duties, imposts, and excises shall be uniform. If the framers had intended to limit the use of the money to the powers afterwards enumerated and defined, nothing could be more easy than to have expressed it plainly.

He knew it was the opinion of some that the words “to pay the debts and provide for the common defense and general welfare” which he had just cited were not intended to be referred to the power of laying taxes contained in the first part of the section but that they are to be understood as distinct and independent powers, granted in general terms. And are gratified by a more detailed enumeration of powers in the subsequent part of the Constitution. He asked the members to read the section with attention and it would, he conceived, plainly appear that such could not be the intention. The whole section seemed to him to be about taxes. It plainly commenced and ended with it and nothing could be more strained than to suppose the intermediate words “to pay the debts and provide for the common defense and general welfare” were to be taken as independent and distinct powers. Forced however as such a construction was, he might admit it and urge that the words do constitute a part of the enumerated powers. The Constitution said he, gives to Congress the power to establish post offices and post roads. He knew the interpretation which was usually given to these words confined our power to that of designating only the post roads, but it seemed to him that the word “establish” comprehended something more.

But suppose the Constitution to be silent said Mr. C, why should we be confined in the application of money to the enumerated powers? There is nothing in the reason of the thing that he could perceive, why it should be so restricted. And the habitual and uniform practice of the Government coincided with his opinion. Our laws are full of instances of money appropriated without any reference to the enumerated powers. If we are restricted in the use of our money to the enumerated powers, on what principle can the purchase of Louisiana be justified? To pass over many other instances, the identical power which is now the subject of discussion has in several instances been exercised. To look no further back, at the last session a considerable sum was granted to complete the Cumberland Road. In reply to this uniform course of legislation, Mr. C. expected it would be said that our Constitution was founded on positive and written principles and not on precedents. He did not deny the position, but he introduced these instances to prove the uniform sense of Congress and the country (for they had not been objected to) as to our powers. And surely they furnish better evidence of the true interpretation of the Constitution than the most refined and subtle arguments.

Let it not be urged that the construction for which he contended gave a dangerous extent to the powers of Congress. In this point of view he conceived it to be more safe than the opposite. By giving a reasonable extent to the money power, it exempted us from the necessity of giving a strained and forced construction to the other enumerated powers.

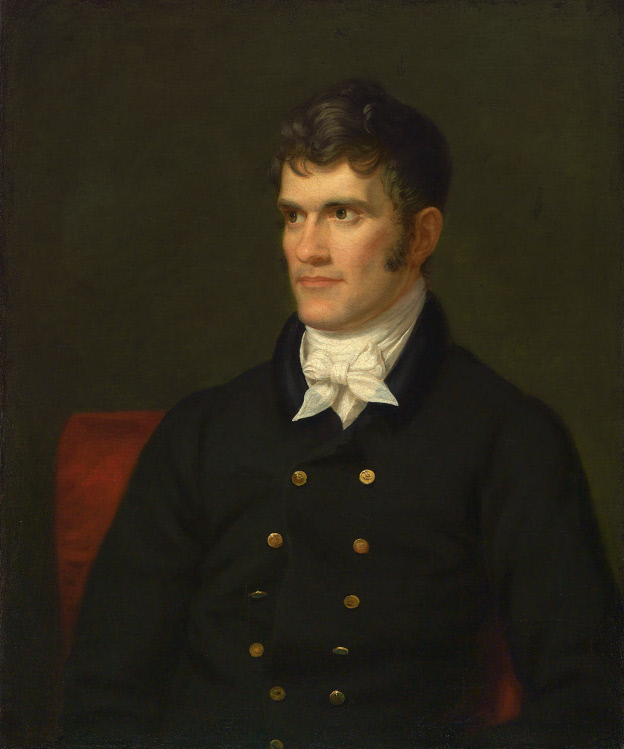

Source: “Argument for Internal Improvements” (1817), by John Caldwell Calhoun in Annals of Congress, 14th Congress, 2nd session. (1854), 851-857. https://archive.org/details/toldcontemporari03hartrich/page/436/mode/2up