181 A Slave Auction (1859)

The largest sale of human chattels that has been made in Star-Spangled America for several years took place on Wednesday and Thursday of last week at the Race Course near the City of Savannah, Georgia. The lot consisted of four hundred and thirty-six men, women, children, and infants, being that half of the negro stock remaining on the old Major Butler plantations which fell to one of the two heirs to that estate.

The largest sale of human chattels that has been made in Star-Spangled America for several years took place on Wednesday and Thursday of last week at the Race Course near the City of Savannah, Georgia. The lot consisted of four hundred and thirty-six men, women, children, and infants, being that half of the negro stock remaining on the old Major Butler plantations which fell to one of the two heirs to that estate.

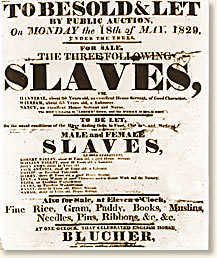

The sale had been advertised largely for many weeks and as the negroes were known to be a choice lot and very desirable property, the attendance of buyers was large. The breaking up of an old family estate is so uncommon an occurrence that the affair was regarded with unusual interest throughout the South. For several days before the sale every hotel in Savannah was crowded with negro speculators from North and South Carolina, Virginia, Georgia, Alabama, and Louisiana, who had been attracted hither by the prospects of making good bargains. Nothing was heard for days in the bar-rooms and public rooms but talk of the great sale, criticisms of the business affairs of Mr. Butler, and speculations as to the probable prices the stock would bring. The office of Joseph Bryan the negro broker who had the management of the sale was thronged every day by eager inquirers in search of information and by some who were anxious to buy but were uncertain as to whether their securities would prove acceptable. Little parties were made up from the various hotels every day to visit the Race Course, distant some three miles from the city, to look over the chattels, discuss their points, and make memoranda for guidance on the day of sale. The buyers were generally of a rough breed, slangy, profane, and bearish, being for the most part from the back river and swamp plantations where the elegancies of polite life are not perhaps developed to their fullest extent.

The negroes came from two plantations, the one a rice plantation near Darien and the other a cotton plantation. None of the Butler slaves have ever been sold before, but have been on these two plantations since they were born. It is true they were sold “in families” but let us see: a man and his wife were called a “family”, their parents and kindred were not taken into account. And no account could be taken of loves that were as yet unconsummated by marriage and how many aching hearts have been divorced by this summary proceeding, no man can ever know.

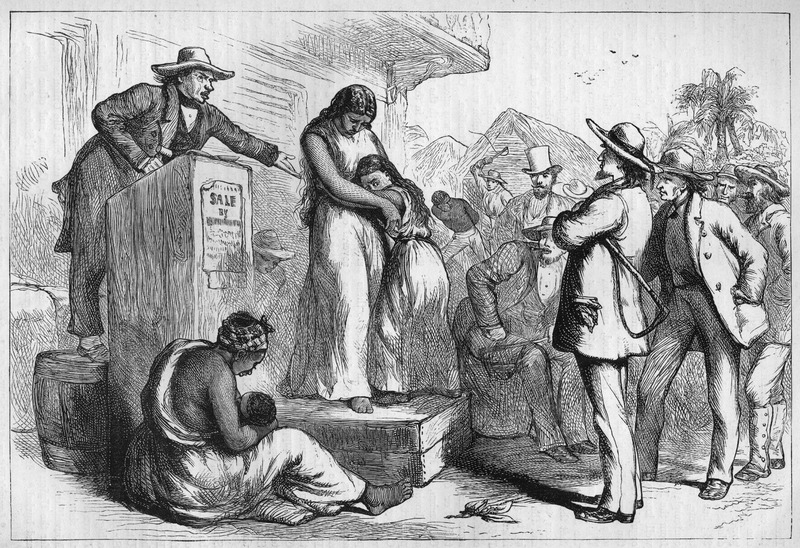

The slaves remained at the race-course, some of them for more than a week and all of them for four days before the sale. They were brought in this early that buyers who desired to inspect them might enjoy that privilege, although none of them were sold at private sale. For these preliminary days their shed was constantly visited by speculators. The negroes were examined with as little consideration as if they had been brutes indeed. The buyers pulling their mouths open to see their teeth, pinching their limbs to find how muscular they were, walking them up and down to detect any signs of lameness, making them stoop and bend in different ways that they might be certain there was no concealed rupture or wound. And in addition to all this treatment, asking them scores of questions relative to their qualifications and accomplishments.

All these humiliations were submitted to without a murmur and in some instances with good-natured cheerfulness — where the slave liked the appearance of the proposed buyer and fancied that he might prove a kind “mas’r”.

Mr. Walsh mounted the stand and announced the terms of the sale, “one-third cash, the remainder payable in two equal annual installments, bearing interest from the day of sale, to be secured by approved mortgage and personal security or approved acceptances on Savannah Ga. or Charleston S. C. Purchasers to pay for papers.” The buyers, who were present to the number of about two hundred, clustered around the platform while the negroes who were not likely to be immediately wanted gathered into sad groups in the background to watch the progress of the selling in which they were so sorrowfully interested. The wind howled outside and through the open side of the building the driving rain came pouring in. The bar downstairs ceased for a short time its brisk trade. The buyers lit fresh cigars, got ready their catalogues and pencils, and the first lot of human chattles are led upon the stand not by a white man but by a sleek mulatto, himself a slave and who seems to regard the selling of his brethren, in which he so glibly assists, as a capital joke. It had been announced that the negroes would be sold in “families”, that is to say a man would not be parted from his wife or a mother from a very young child. There is perhaps as much policy as humanity in this arrangement, for thereby many aged and unserviceable people are disposed of who otherwise would not find a ready sale.

The expression on the faces of all who stepped on the block was always the same and told of more anguish than it is in the power of words to express. Blighted homes, crushed hopes, and broken hearts was the sad story to be read in all the anxious faces. Some of them regarded the sale with perfect indifference, never making a motion save to turn from one side to the other at the word of the dapper Mr. Bryan that all the crowd might have a fair view of their proportions, and then, when the sale was accomplished, stepping down from the block without caring to cast even a look at the buyer who now held all their happiness in his hands. Others, again, strained their eyes with eager glances from one buyer to another as the bidding went on, trying with earnest attention to follow the rapid voice of the auctioneer. Sometimes, two persons only would be bidding for the same chattel, all the others having resigned the contest. And then the poor creature on the block, conceiving an instantaneous preference for one of the buyers over the other, would regard the rivalry with the intensest interest, the expression of his face changing with every bid, settling into a half smile of joy if the favorite buyer persevered unto the end and secured the property and settling down into a look of hopeless despair if the other won the victory.

The auctioneer brought up Joshua’s Molly and family. He announced that Molly insisted that she was lame in her left foot and perversely would walk lame, although for his part he did not believe a word of it. He had caused her to be examined by an eminent physician in Savannah, which medical light had declared that Joshua’s Molly was not lame but was only shamming. However, the gentlemen must judge for themselves and bid accordingly. So Molly was put through her paces and compelled to trot up and down along the stage, to go up and down the steps, and to exercise her feet in various ways but always with the same result, the left foot would be lame. She was finally sold for $695.

Whether she really was lame or not, no one knows but herself, but it must be remembered that to a slave a lameness or anything that decreases his market value is a thing to be rejoiced over. A man in the prime of life, worth $1,600 or thereabouts, can have little hope of ever being able by any little savings of his own to purchase his liberty. But let him have a rupture or lose a limb or sustain any other injury that renders him of much less service to his owner and reduces his value to $300 or $400, and he may hope to accumulate that sum and eventually to purchase his liberty. Freedom without health is infinitely sweeter than health without freedom.

And so the Great Sale went on for two long days, during which time there were sold 429 men, women, and children. There were 436 announced to be sold, but a few were detained on the plantations by sickness. The total amount of the sale foots up $303,850 — the proceeds of the first day being $161,480 and of the second day $142,370.

Leaving the Race buildings where the scenes we have described took place, a crowd of negroes were seen gathered eagerly about a man in their midst. That man was Mr. Pierce M. Butler of the free city of Philadelphia, who was solacing the wounded hearts of the people he had sold from their firesides and their homes by doling out to them small change at the rate of a dollar a head. To every negro he had sold who presented his claim for the paltry pittance he gave the munificent stipend of one whole dollar in specie; he being provided with two canvas bags of 35 cent pieces, fresh from the mint, to give an additional glitter to his munificent generosity.

Source: Horace Greeley, New-York Daily Tribune, March 9, 1859. https://archive.org/details/americanhistoryt00ivunse/page/74/mode/2up