146 Texas Revolution (1836)

It is necessary in the first place, to announce the fact that on the 2nd of March, 1836, the declaration of Texan independence was proclaimed. The condition of the country at that time I will not particularly explain, but a provisional government had existed previous to that time. In December, 1835, when the troubles first began in Texas in the inception of its revolution, Houston was appointed major general of the forces by the consultation then in session at San Felipe. He remained in that position. A delegate from each municipality, or what would correspond to counties here, was to constitute the government, with a Governor, Lieutenant Governor, and Council. They had the power of the country. An army was requisite and means were necessary to sustain the revolution. This was the first organization of anything like a government, which absorbed the power that had previously existed in committees of vigilance and safety in different sections of the country. When the general was appointed, his first act was to organize a force to repel an invading army which he was satisfied would advance upon Texas. A rendezvous had been established at which the drilling and organization of the troops was to take place and officers were sent to their respective posts for the purpose of recruiting men. Colonel Fannin was appointed at Matagorda to superintend that district, second in command to the General-in-Chief, and he remained there until the gallant band from Alabama and Georgia visited that country. They were volunteers under Colonels Ward, Shackleford, Duvall, and other illustrious names. When they arrived Colonel Fannin, disregarding the orders of the Commander-in-Chief, became by countenance of the council a candidate for commander of the volunteers. Some four or five hundred of them had arrived, all equipped and disciplined; men of intelligence, men of character, men of chivalry and of honor. A more gallant band never graced the American soil in defense of liberty. He was selected and the project of the council was to invade Matamoras under the auspices of Fannin. San Antonio had been taken in 1835. Troops were to remain there. It was a post more than seventy miles from any colonies or settlements by the Americans. It was a Spanish town or city with many thousand population and very few Americans. The Alamo was nothing more than a church and derived its cognomen from the fact of its being surrounded by poplars or cotton-wood trees. The Alamo was known as a fortress since the Mexican revolution in 1812.

The Commander-in-Chief sent an order to Colonel Neill who was in command of the Alamo, to blow up that place and fall back to Gonzales, making that a defensive position which was supposed to be the furthest boundary the enemy would ever reach. This was on the 17th of January. That order was secretly superseded by the council and Colonel Travis, having relieved Colonel Neill, did not blow up the Alamo and retreat with such articles as were necessary for the defense of the country, but remained in possession from the 17th of January until the last of February, when the Alamo was invested by the force of Santa Anna. Surrounded there and cut off from all succor, the consequence was they were destroyed. They fell victims to the ruthless feelings of Santa Anna, by the contrivance of the council and in violation of the plans of the major general for the defense of the country.

The general proceeded on his way and met many fugitives. The day on which he left Washington, the 6th of March, the Alamo had fallen. He anticipated it and marching to Gonzales as soon as practicable, though his health was infirm, he arrived there on the 11th of March. He found at Gonzales three hundred and seventy-four men half fed, half clad, and half armed, and without organization. That was the nucleus on which he had to form an army and defend the country. No sooner did he arrive than he sent a dispatch to Colonel Fannin, fifty-eight miles which would reach him in thirty hours, to fall back. He was satisfied that the Alamo had fallen. Colonel Fannin was ordered to fall back from Goliad, twenty-five miles to Victoria on the Guadalupe. He received an answer from Colonel Fannin stating that he had received his order, had held a council of war, and that he had determined to defend the place and called it Fort Defiance and had taken the responsibility to disobey the order.

Fannin after disobeying orders, attempted on the 19th to retreat, and had only twenty-five miles to reach Victoria. His opinions of chivalry and honor were such that he would not avail himself of the night to do it in, although he had been admonished by the smoke of the enemies’ encampment for eight days previous to attempting a retreat. He then attempted to retreat in open day. The Mexican cavalry surrounded him. He halted in a prairie without water, commenced a fortification and there was surrounded by the enemy who, from the hill tops, shot down upon him. Though the most gallant spirits were there with him, he remained in that situation all that night and the next day when a flag of truce was presented. He entered into a capitulation and was taken to Goliad on a promise to be returned to the United States with all associated with him. In less than eight days, the attempt was made to massacre him and every man with him. I believe some few did escape, most of whom came afterwards and joined the army.

The general fell back from the Colorado. He marched and took position on the Brazos with as much expedition as was consistent with his situation. On the Brazos, the efficient force under his command amounted to five hundred and twenty. The encampment on the Brazos was the point at which the first piece of artillery was ever received by the army. They were without munitions. Old horseshoes and all pieces of iron that could be procured had to be cut up. Various things were to be provided; there were no cartridges and but few balls. Two small six-pounders, presented by the magnanimity of the people of Cincinnati and subsequently called the “twin sisters” were the first pieces of artillery that were used in Texas. From thence, the march commenced at Donoho’s, three miles from Groce’s. It had required several days to cross the Brazos with the horses and wagons. A crossing was effected by the evening and the line of march was taken up for San Jacinto, for the purpose of cutting off Santa Anna below the junction of the San Jacinto and Buffalo bayou.

In the morning the sun had risen brightly and he determined with this omen, “today the battle shall take place.” The plan of battle is described in the official report of the Commander-in-Chief, to be found in Yoakum’s history, one of the most authentic and valuable books in connection with the general affairs of Texas that can be found, in which nothing is stated upon individual responsibility. Everything in it is sustained by the official documents.

With the exception of the Commander-in-Chief, no gentleman in the army had ever been in a general action or even witnessed one. No one had been drilled in a regular army or had been accustomed to the evolutions necessary to the maneuvering of troops. So soon as the disposition of the troops was made according to his judgment, he announced to the Secretary of War the plan of battle. It was concurred in instantly. The Commander-in-Chief requested the Secretary of War to take command of the left wing, so as to possess him of the timber and enable him to turn the right wing of the enemy. The general’s plan of battle was carried out.

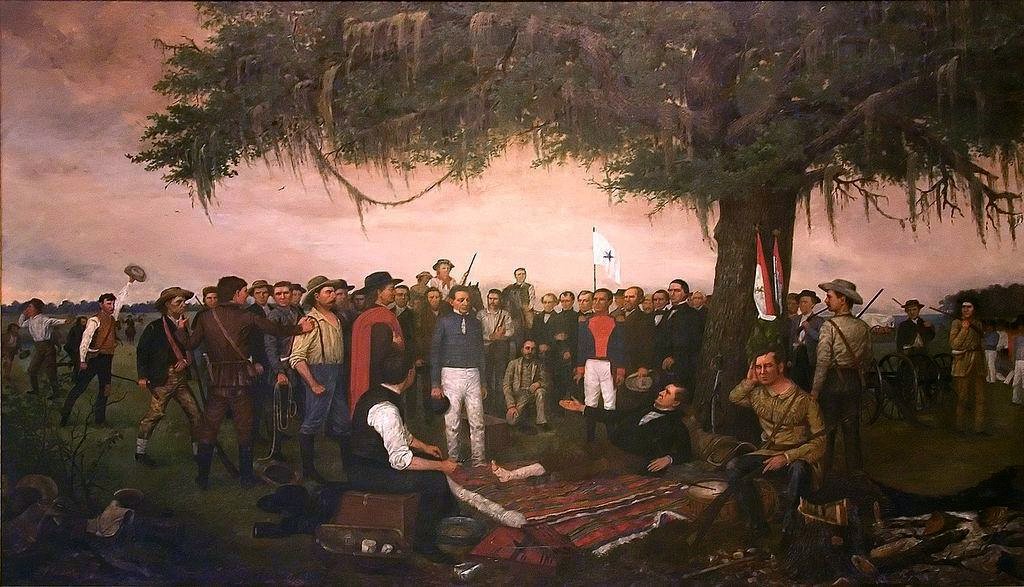

Now Mr. President, notwithstanding the various slanders that have been circulated about the Commander-in-Chief, it is somewhat strange that the only point about which there has been no contestation for fame and for heroic wreaths is in relation to the circumstances connected with the capture of General Santa Anna. When he was brought into the camp and the interview took place, the Commander-in-Chief was lying on the ground. Looking up he saw Santa Anna, who announced to him in Spanish, “I am General Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna, President of the Republic of Mexico and a prisoner at your disposition.” Calmly and quietly it was received. The hand was waved to a box that stood by and there Santa Anna was seated. After some time, with apparent emotion but with great composure to what I had expected under the circumstances, he proposed a negotiation for his liberation. He was informed that the general had not the power, that there was an organized civil Government and it must be referred to them. Santa Anna insisted upon negotiation and expressed his great aversion to all civil government. The general assured him that he could not do it.

Source: Congressional Globe, 35th Congress, 2nd session (1859), 1433-1438. https://archive.org/details/toldcontemporari03hartrich/page/636/mode/2up