77 The Settlement of the Western Country (1772-1774)

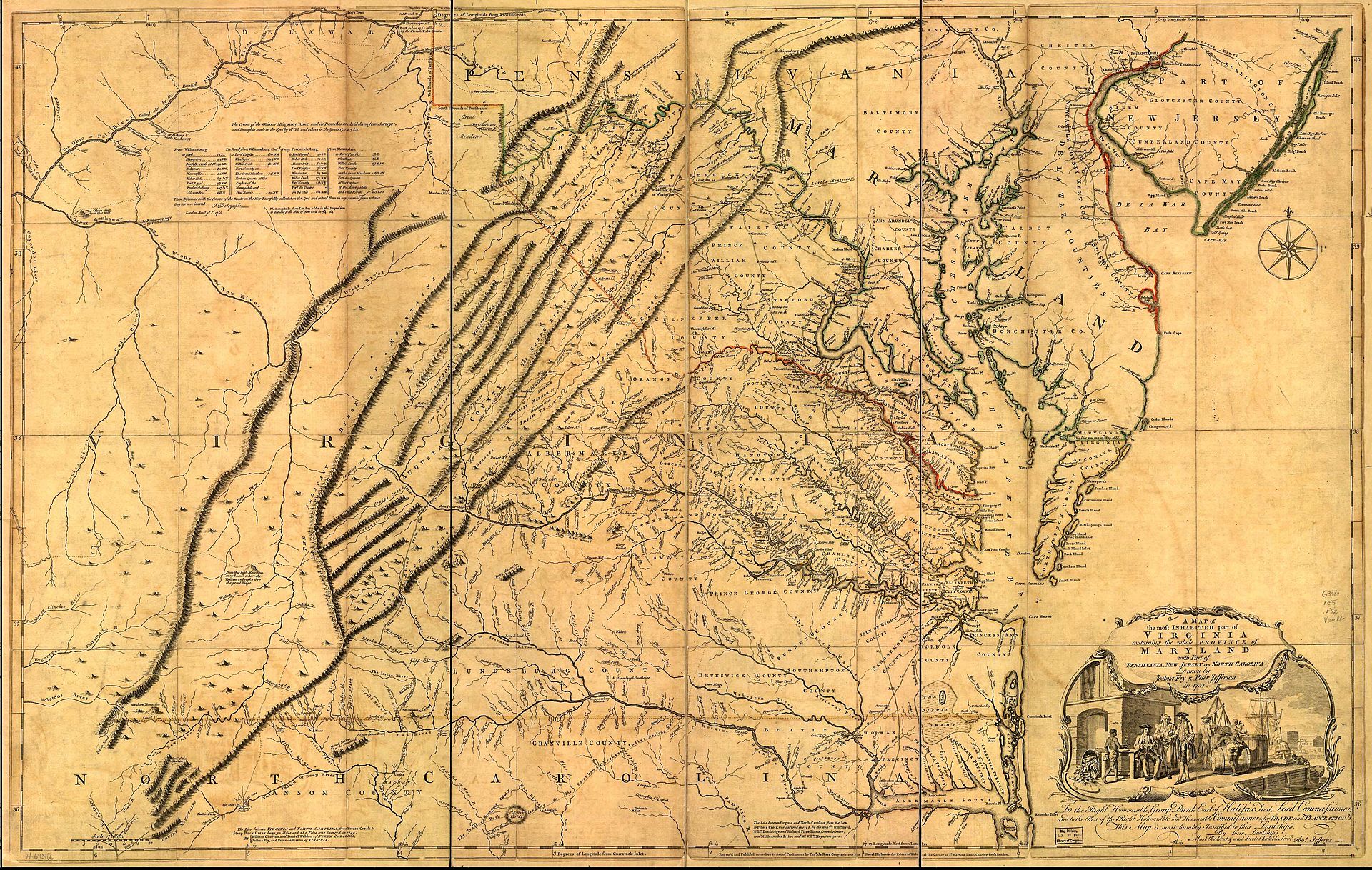

The Settlements on this side of the mountains commenced along the Monongahela and between that river and the Laurel Ridge in the year 1772. In the succeeding year they reached the Ohio river. The greater number of the first settlers came from the upper parts of the then colonies of Maryland and Virginia. Braddock’s trail, as it was called, was the route by which the greater number of them crossed the mountains. A less number of them came by the way of Bedford and Fort Ligonier, the military road from Pennsylvania to Pittsburgh. They effected their removals on horses furnished with pack-saddles. This was the more easily done, as but few of these early adventurers into the wilderness were encumbered with much baggage.

Land was the object which invited the greater number of these people to cross the mountain. For as the saying then was, “It was to be had here for taking up.” That is, building a cabin and raising a crop of grain however small entitled the occupant to four hundred acres of land and a preemption right to one thousand acres more adjoining, to be secured by a land office warrant. This right was to take effect if there happened to be so much vacant land or any part thereof adjoining the tract secured by the settlement right. At an early period, the government of Virginia appointed three commissioners to give certificates of settlement rights. These certificates together with the surveyor’s plat were sent to the land office of the state, where they laid six months to await any caveat [challenge] which might be offered. If none was offered the patent then issued.

There was at an early period of our settlements an inferior kind of land title denominated a “tomahawk right,” which was made by deadening a few trees near the head of a spring and marking the bark of some one or more of them with the initials of the name of the person who made the improvement. I remember having seen a number of those “tomahawk rights” when a boy. For a long time many of them bore the names of those who made them. I have no knowledge of the efficacy of the tomahawk improvement or whether it conferred any right whatever, unless followed by an actual settlement. These rights however were often bought and sold. Those who wished to make settlements on their favorite tracts of land bought up the tomahawk improvements rather than enter into quarrels with those who had made them. Other improvers of the land with a view to actual settlement and who happened to be stout veteran fellows took a very different course from that of purchasing the “tomahawk rights.” When annoyed by the claimants under those rights, they deliberately cut a few good hickories and gave them what was called in those days “a laced jacket,” that is a sound whipping.

Some of the early settlers took the precaution to come over the mountains in the spring, leaving their families behind to raise a crop of corn and then return and bring them out in the fall. This I should think was the better way. Others, especially those whose families were small, brought them with them in the spring. My father took the latter course. His family was but small and he brought them all with him. The Indian meal which he brought over the mountain was expended six weeks too soon, so that for that length of time we had to live without bread. The lean venison and the breast of the wild turkeys we were taught to call bread. The flesh of the bear was denominated meat. This artifice did not succeed very well. After living in this way for some time we became sickly, the stomach seemed to be always empty and tormented with a sense of hunger. I remember how narrowly the children watched the growth of the potato tops, pumpkin, and squash vines, hoping from day to day to get something to answer in the place of bread. How delicious was the taste of the young potatoes when we got them! What a jubilee when we were permitted to pull the young corn for roasting ears. Still more so when it had acquired sufficient hardness to be made into johnny cakes by the aid of a tin grater. We then became healthy, vigorous and contented with our situation, poor as it was.

My father with a small number of his neighbors made their settlements in the spring of 1773. Though they were in a poor and destitute situation, they nevertheless lived in peace. But their tranquility was not of long continuance. Those most atrocious murders of the peaceable inoffensive Indians at Captina and Yellow Creek brought on the War of Lord Dunmore in the spring of the year 1774. Our little settlement then broke up. The women and children were removed to Morris’ Fort in Sandy Creek glade some distance to the east of Uniontown. The fort consisted of an assemblage of small hovels situated on the margin of a large and noxious marsh, the effluvia of which gave most of the women and children the fever and ague. The men were compelled by necessity to return home and risk the tomahawk and scalping knife of the Indians, in raising corn to keep their families from starvation the succeeding winter. Those sufferings, dangers, and losses were the tribute we had to pay to that thirst for blood which actuated those veteran murderers who brought the war upon us! The memory of the sufferers in this war as well as that of their descendants still looks back upon them with regret and abhorrence, and the page of history will consign their names to posterity with the full weight of infamy they deserve.

My father like many others believed that having secured his legal allotment, the rest of the country belonged of right to those who choose to settle in it. There was a piece of vacant land adjoining his tract amounting to about two hundred acres. To this tract of land he had the preemption right and accordingly secured it by warrant. But his conscience would not permit him to retain it in his family; he therefore gave it to an apprentice lad whom he had raised in his house. This lad sold it to an uncle of mine for a cow and calf and a wool hat.

The division lines between those whose lands adjoined were generally made in an amicable manner, before any survey of them was made, by the parties concerned. In doing this they were guided mainly by the tops of ridges and water courses, but particularly the former. Hence the greater number of farms in the western parts of Pennsylvania and Virginia bear a striking resemblance to an amphitheater. The buildings occupy a low situation and the tops of the surrounding hills are the boundaries of the tract to which the family mansion belongs. Our forefathers were fond of farms of this description because, as they said, they are attended with this convenience “that everything comes to the house down-hill.” In the hilly parts of the state of Ohio, the land having been laid off in an arbitrary manner by straight parallel lines without regard to hill or dale, the farms present a different aspect from those on the east side of the river opposite. There the buildings as frequently occupy the tops of the hills as any other situation.

Our people had become so accustomed to the mode of “getting land for taking it up,” that for a long time it was generally believed that the land on the west side of the Ohio would ultimately be disposed of in that way. Hence almost the whole tract of country between the Ohio and Muskingum was parceled out in tomahawk improvements, but these latter improvers did not content themselves with a single four-hundred acre tract apiece. Many of them owned a great number of tracts of the best land and thus in imagination were as “Wealthy as a South Sea Dream.” Many of the land jobbers of this class did not content themselves with marking the trees at the usual height with the initials of their names, but climbed up the large beech trees and cut the letters in their bark, from twenty to forty feet from the ground. To enable them to identify those trees at a future period they made marks on other trees around them as references.

Source: The Settlement of the Western Country (1772-1774), Joseph Doddridge, Notes on the Settlement and Indian Wars of the Western Parts of Virginia & Pennsylvania (1824), 99-112. https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.45494/page/n411/mode/2up