66 The Beautiful River (1752)

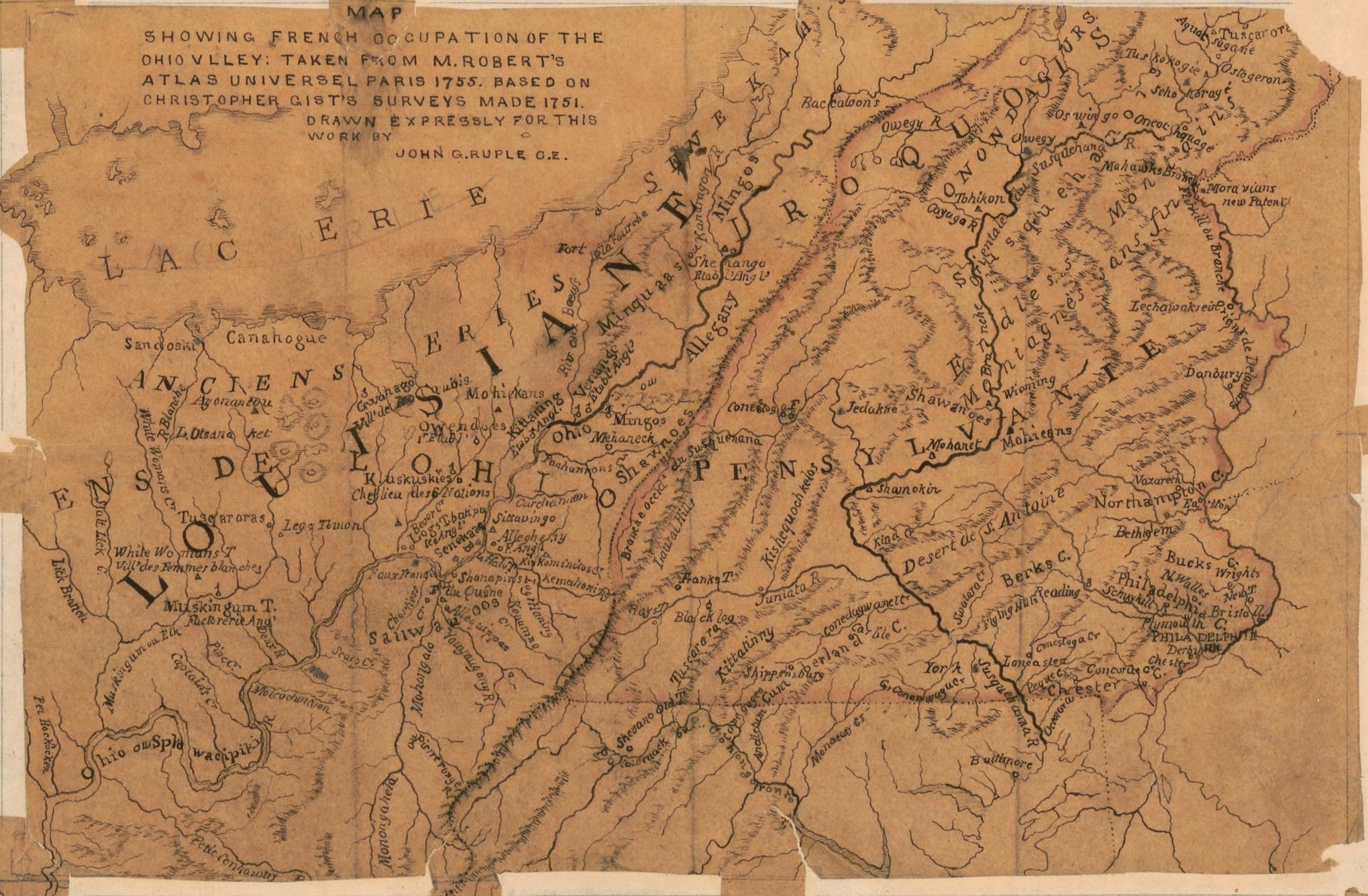

The Ohio, or “la Belle Riviere,” was the tributary of the Mississippi having branches nearest to the English settlements, and thus became the center of the conflict for the possessions of the West.

It appears from a letter of the Marquis de la Jonquiere that the efforts the English are making and the expenses they incur, to gain over the Indians, are not without success among several Nations. Information has been received last year of the progress they had already made among the Indians in the environs of the River Ohio, where they have undertaken since the peace to form some establishments.

The Marquis de la Jonquiere had rendered an account of a plan he had prepared both to drive the English from that river and to chastise the Indians who allowed themselves to be gained over. But all the consequent operations reduce themselves to the seizure of some English traders with their goods and to the murder of two Indians of the Miami’s Nation. The seizure of the English traders whose effects have been confiscated and even plundered by our [French-allied] Indians cannot but produce a good effect, by disgusting the other traders of that Nation.

The English may pretend that we are bound by the Treaty of Utrecht [1713, ending the War of the Spanish Succession] to permit the Indians to trade with them. But it is certain that nothing can oblige us to suffer this trade on our territory. Accordingly in all the alliances or quasi-treaties or propositions we have had with the Far Indians, we have never obliged them expressly to renounce going to the English to trade. We have merely exhorted them to that effect and never did we oppose that treaty by force.

The River Ohio, otherwise called the Beautiful river, and its tributaries belong indisputably to France by virtue of its discovery by Sieur de La Salle, of the trading posts the French have had there since, and of possession which is so much the more unquestionable as it constitutes the most frequent communication from Canada to Louisiana. It is only within a few years that the English have undertaken to trade there and now they pretend [claim] to exclude us from it.

They have not up to the present time, however, maintained that these rivers belong to them. They pretend only that the Iroquois are masters of them and being the sovereigns of these Indians, that they can exercise their rights. But ’tis certain that these Indians have none and that besides, the pretended sovereignty of the English over them is a chimera.

Meanwhile ’tis of the greatest importance to arrest the progress of the pretensions and expeditions of the English in that quarter. Should they succeed there, they would cut off the communication between the two Colonies of Canada and Louisiana and would be in a position to trouble them and to ruin both the one and the other, independent of the advantages they would at once experience in their trade to the prejudice of ours.

Any complaints that may be presented to the Court of England against the English Governors would be altogether futile. On the one hand it would be very difficult to obtain proofs of the most serious facts. And on the other, no matter what proofs may be produced, that Court would find means to elude all satisfaction; especially as long as the boundaries are not settled.

It is necessary then to act on the spot and the question to be determined is, what means are the most proper. Therefore, without undertaking as the Marquis de la Jonquiere appears to have proposed to drive from the River Ohio the Indians who are looked upon as rebels or suspected, and without wishing even to destroy the liberty of their trade, it is thought best to adhere to two principal points.

1st, To make every possible effort to drive the English from our territory and to prevent them coming there to trade.

2nd, To give the Indians to understand at the same time that no harm is intended them, that they will have liberty to go as much as they please to the English to trade, but will not be allowed to receive these on our territory.

There is reason to believe that by this course of conduct: by providing our posts with plenty of goods and preventing our traders dictating to the Indians, our trade will soon recover the superiority over that of the English in those parts. For ’tis certain the Indians do not like to go into their towns nor forts.

However that be, ’tis considered proper to direct Mr. Duquesne to lay down henceforward in Canada a different system from that always followed hitherto in regard to wars among the Indians. With a view to occupy and weaken them, the principle has been to excite and foment these sorts of wars. That was of advantage in the infancy of the settlement of Canada. But in the condition to which these Nations are now reduced and in their present dispositions generally, it is in every respect more useful that the French perform between them the part of protectors and pacificators. They will thereby entertain more consideration and attachment for us. The Colony will be more tranquil in consequence and we shall save considerable expense. Cases, however, may occur in which it will be proper to excite war against certain Nations attached to the English. But even such cases call for two observations: one, to endeavor first to gain over these same Nations by reconciling them with ours. And the other, to be as sure as possible that our Indians will not suffer too much from these wars.

Source: “French Title to the Beautiful River” (1752) from French Royal Ministry Minutes, in E. B. O’Callaghan, editor, Documents relative to the Colonial History of the State of New-York (Albany, 1858), X, 242-244. https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.45494/page/n377/mode/2up