23 Dismasking of Virginia (1622)

Captain Nathaniel Butler was an English privateer and governor of Bermuda. In 1621 he visited Jamestown for about a year and wrote a scathing report he presented to the King’s Privy Council.

I found the plantations generally seated upon mere salt marshes, full of infectious bogs and muddy creeks and lakes, and hereby subjected to all those inconveniences and diseases which are so commonly found in the most unsound and most unhealthy parts of England, whereof every country and climate has some.

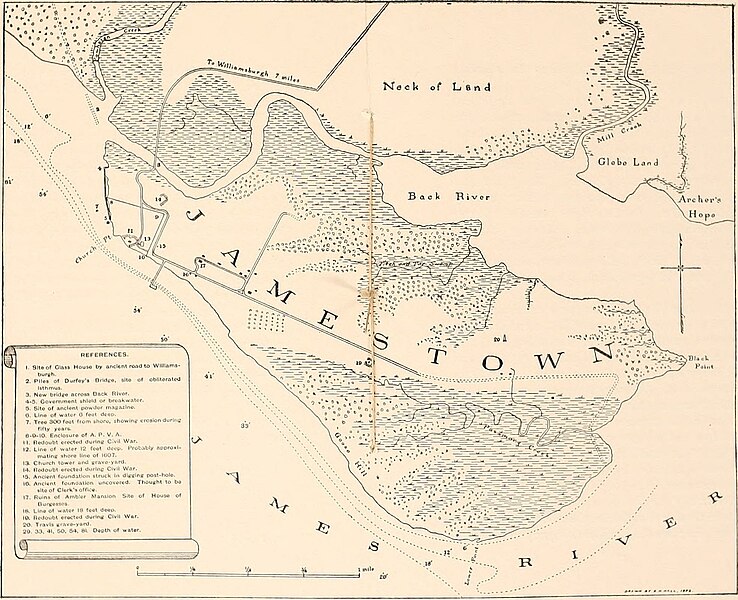

I found the shores and sides of those parts of the main river where our plantations are settled, everywhere so shallow that no boats can approach the shores. So that besides the difficulty, danger, and spoil of goods in the landing of them, the poor people are forced to the continual wading and wetting themselves. And that in the prime of winter when the ships commonly arrive and thereby get such violent surfeits of cold upon cold as seldom leave them until they leave to live.

The new people that are yearly sent over, which arrive here for the most part very unseasonably in winter, find neither guest-house, inn, nor any the like place to shroud themselves in at their arrival. No, not so much as a stroke given towards any such charitable work, so that many of them by want hereof are not only seen dying under hedges and in the woods, but being dead lie some of them for many days unregarded and unburied.

The colony was this winter in much distress of victual, so that English meal [wheat] was sold at the rate of thirty shillings a bushel, their own native corn, called maize, at ten and fifteen shillings per bushel. The which, howsoever it lay heavy upon the shoulders of the generality [common people], it may be suspected not to be unaffected by some of the chief. For they only having the means in those extremities to trade with the natives for corn, do hereby engross all into their own hands and to sell it abroad at their own prices. And I myself have heard from the mouth of a prime one among them that he would never wish that their own corn should be cheaper amongst them than eight shillings the bushel.

Their houses are generally the worst that ever I saw, the meanest cottages in England being every way equal (if not superior) with the most of the best. And besides, so improvidently and scatteringly are they seated one from another, as partly by their distance, but especially by the interposition of creeks and swamps, as they call them, they offer all advantages to their savage enemies and are utterly deprived of all sudden recollection of themselves upon any terms whatsoever.

I found not the least piece of fortification; three pieces of ordnance only mounted at James City, and one at Flowered Hundreds, but never a one of them serviceable. So that it is most certain that a small bark of a hundred ton may take its time to pass up the river in spite of them and coming to an anchor before the town may beat all their houses down about their ears, and so forcing them to retreat into the woods may land under the favor of their ordnance and rifle the town at pleasure.

Expecting, according to their printed books, a great forwardness of diverse and sundry commodities at mine arrival, I found not any one of them so much as in any fowardness of being. For the iron works were utterly wasted and the men dead, the furnaces for glass and pots at a stay, and small hopes. As for the rest they were had in a general derision even amongst themselves and the pamphlets that had published there, being sent thither by hundreds, were laughed to scorn. And every base fellow boldly gave them the lie in diverse particulars. So that tobacco only was the business and for aught that I could hear every man madded [focused] upon that little thought nor looked for anything else.

I found the ancient plantations of Henrico and Charles City wholly quitted and left to the spoil of the Indians, who not only burnt the houses, said to be once the best of all others, but fell upon the poultry, hogs, cows, goats, and horses. Whereof they killed great numbers, to the great grief as well as ruin of the old inhabitants, who stick not to affirm that these were not only the best and healthiest parts of all others but might also, by their natural strength of situation, have been the most easily preserved of all others.

Whereas, according to his Majesty’s most gracious letters-patents, his people are as near as possibly may be to be governed after the excellent laws and customs of England, I found in the Government here not only ignorant and enforced strayings in diverse particulars, but willful and intended ones. In so much as some who urged due conformity have in contempt been termed men of law and were excluded from those rights which by orderly proceedings they were elected and sworn unto here.

There having been as it is thought not fewer than ten thousand souls transported thither, there are not, through the aforementioned abuses and neglects, above two thousand of them to be found alive at this present … many of them also in a sickly and desperate state. So that it may undoubtedly be expected that unless the confusions and private ends of some of the Company here and the bad execution in seconding them by their agents there be redressed with speed by some divine and supreme hand, that instead of a plantation it will get the name of a slaughter-house and so justly become both odious to ourselves and contemptible to all the world.

Source: “Unmasked Face of Our Colony in Virginia as it was in the winter of the Year 1622”, by Captain Nathaniel Butler in Abstract of the Proceedings of the Virginia Company of London, in Virginia Historical Society, Collections, VIII (Richmond, 1889), 11, 171-173. In Hart, American History Told by Contemporaries, 225-7. https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.45493/page/n245/mode/2up