Foundational Components

In the domain of classroom management, five foundational components are essential for creating a conducive learning environment: the Physical Design of the Classroom, Establishment of Routines, Development of Positively Stated Expectations & Rules, Implementation of Culturally Responsive Anti-racist Teaching Practices, and Integration of Social Emotional Learning.

Begin by viewing the following video: (Establish a Consistent, Organized, and Respectful Learning Environment 20:14)

Physical Design of the Classroom

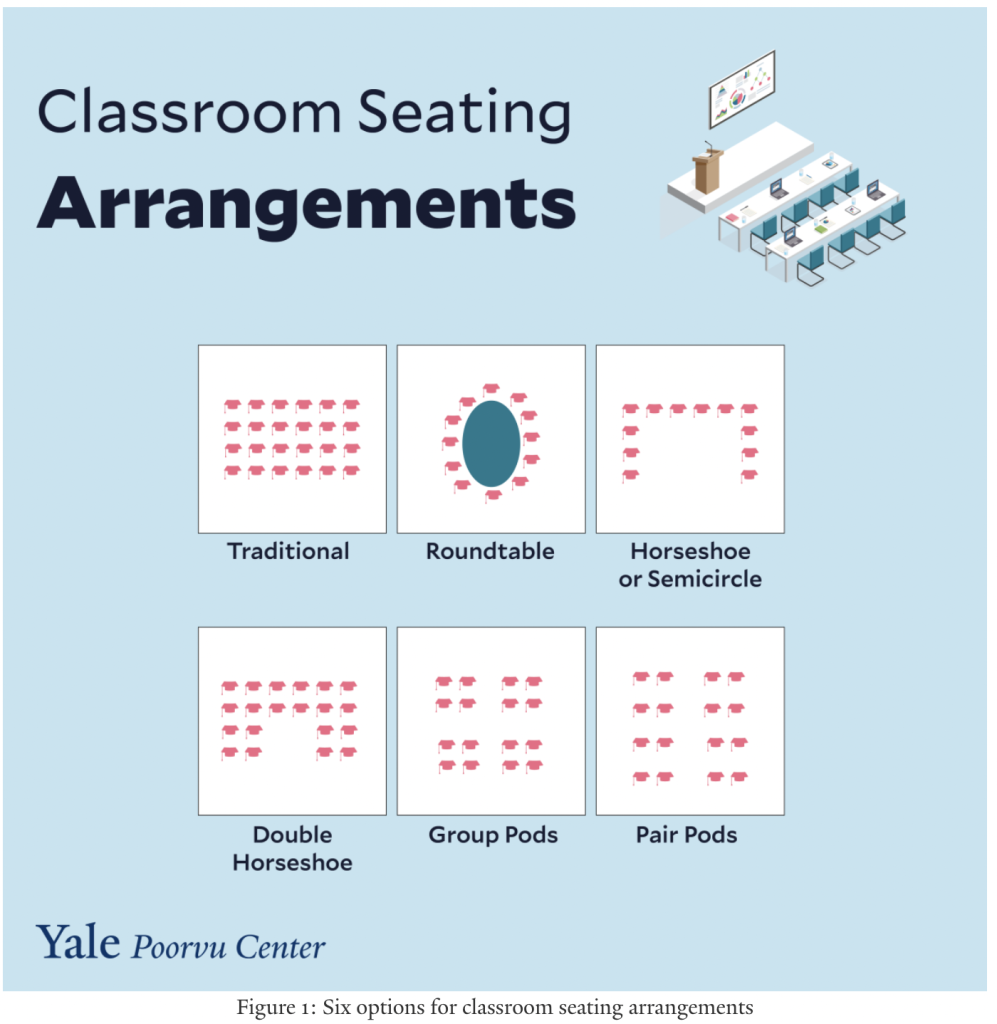

The design and layout of the classroom can support classroom management in multiple ways. Teachers can circumvent some problems by strategically arranging the environment. The set-up should work for the types of instructional activities mostly used, whether that be small groups, partner work, the whole group, stations, etc. Consider the flow of traffic and movement of both the students and the teacher. Make sure that all necessary areas are accessible and that you can see all the students. Figure 1 provides a visual of six common seating arrangements.

FIGURE 1: Classroom Seating Arrangements. Yale Poorvu Center.

The following materials provide additional insights:

The following materials provide additional insights:

- View this video: Setting Up Your Classroom Environment: Management in the Active Classroom 1:07)

- Listen to this podcast: 12 Ways to Upgrade Your Classroom Design. (44:21).

Materials are included in the physical layout as well. Materials should be orderly and ready for use. Also consider what is on the walls and writable spaces. Use wall space to post content that supports learning, but be aware that too much content on the walls can be overwhelming. This is also an opportunity to include materials, images, and expected practices to honor diverse backgrounds.

Routines

Establishing routines for common activities in the classroom is necessary for both saving time and managing behaviors and expectations. Classroom routines allow for teaching and learning to occur in a group where the members of that community have a strong sense of what to expect. When students do not know what to expect, both academically and behaviorally, it can lead to frustration and confusion. To begin the implementation of classroom routines, the teacher needs to examine the activities that happen on a regular basis and outline the steps required for those common activities. Then, it is necessary to explicitly teach those routines, step by step. Practice is also necessary, and teachers with solid routines have spent the time to practice those routines with students repeatedly. Once students have begun to follow routines, it is critical to then recognize and celebrate when students successfully complete those routines. One way to think about the options for classroom routines is to classify them into four categories: opening, operating, teaching, and closing.

- Opening routines: When students come in, do they know what to do to get started and focused?

- Operating routines

- Teaching routines

- Closing routines: Just as you would set routines for entering the room, students should know what needs to be done to close out a class period or school day.

Classroom routines are also a way to operationalize school wide expectations. Oftentimes, we see school wide expectations such as “Be respectful” and “Be responsible,” but what does that mean in a classroom? As a teacher, it is critical to understand the cultural assumptions that go along with these expectations. For example, routines can be built around independent work (Myers et al., 2017).

The following materials provide additional insights:

- View this video about classroom routines. (Building Strong Foundations With Classroom Routines 1:39)

- Listen to this podcast on Routines and Procedures with Dr. Catlin Tucker (48:56)

- Read this post about Rules and Routines in Elementary and Secondary Classrooms.

Positively Stated Expectations & Rules

Classroom rules and expectations are not a new idea when thinking about key supports for classroom management. All students do better when expectations are clear and achievable (Simonsen et al., 2015). Overall, classroom rules should be limited to three to five key rules, aligned with school wide rules, easy to understand, positively stated, always applicable, and useful in a wide variety of situations across the school day and setting (Hester et al., 2009; Myers et al., 2017; Simonsen et. al, 2015). Rules are more meaningful to students when they are involved in defining and deciding which rules should be in place in their classroom routines. This can lead to greater commitment to rule adherence and setting rules as an expected norm for the group.

As a practice, there are two characteristics of classroom rules that are particularly effective: connecting rules to a positive or negative consequence (discussed later in the chapter) and the explicit teaching of classroom rules. It is necessary to spend the time teaching the rules and expectations, with plenty of examples and non-examples. Depending on the students’ age, it may be helpful to quickly review the rules daily and should be reinforced by having them posted in the classroom.

The following materials provide additional insights:

- View Classroom Expectations and Rules (11:49)

- Read this article: Setting Classroom Rules WITH Students.

- Listen to this podcast: 10 Keys for Rules in the Classroom. (26:43)

Culturally Responsive Anti-Racist Teaching Practices

Historically, classroom management practices have not been reflective of ethnic or cultural diversity. Teachers need to be aware of how a student’s background and culture may interact with styles of classroom management. There is extensive documentation showing disparities in the use of classroom and school wide discipline based on race, socioeconomics, and gender. Teachers must examine their own thoughts and address biases within their classroom management styles and preferences. One way to do this is to consider a few key aspects that support the values of anti-racist teaching practices:

- Commit to creating a safe, inclusive community where all students and teachers are respected.

- Disciplinary incidents must be treated as opportunities for growth, restitution, and community building.

- Behavior management practices must address issues of fairness, equity, and cultural awareness (From SPLC: Learning for Justice).

These considerations support culturally responsive teaching practices, which are necessary in the development of a positive and supportive learning environment. Yet, how do we operationalize these values? Taylor and Bhana (2021) detail some practical suggestions for implementing culturally responsive teaching practices for classroom management. These practices include centering on creating collaborative partnerships that encourage and share student ownership of the classroom, creating a space where students feel that mistakes and conflicts are part of the learning process and can be rectified, and the use of curriculum and teaching methods that are accessible to and represent students.

The following materials provide additional insights:

- Extend your learning: Critical Practices for Anti-bias Education: Classroom Culture

- Read this article: Checking Yourself for Bias in the Classroom.

- Listen to this podcast on Creating Brave Spaces: Reckoning with Race in the Classroom. (1:08:27)

Social Emotional Learning

First, view: 5 Keys to Social and Emotional Learning Success (6:02)

As shared in the video, teachers need to spend time developing positive relationships with their students, but it is also necessary to support students in developing their own social and emotional learning (SEL) and skills. Studies have shown that implementing social emotional learning practices has a positive impact on student behaviors and attitudes, decreases emotional distress, and increases academic performance (Durlak et al., 2011). As discussed in other sections, implementing social emotional learning practices can help students develop trusting relationships, build empathy, and keep students in the learning environment with their peers. These practices are also sensitive to the cultural and school context of behavior, which focuses on avoiding disproportionality for students from different cultural backgrounds and harsher punishments.

As part of a classroom management plan, social emotional learning can take many forms. The Art of Education gives some specific examples of what SEL for classroom management looks like:

- A safe and welcoming space, where students are greeted as they come in. They are given the opportunity to do a well-being check-in prior to working. There are consistent expectations for where to go and what to do.

- Students are empowered to take charge. They know how to be prepared and know what is going to happen next. They know where materials are and what they are free to use.

- The adults model apologies. Students need to see that it is okay to admit a mistake and understand the power of a clear and meaningful apology.

- Students get to check-in on a regular basis. This can be done with a variety of mood meters and surveys, which helps students increase their self-awareness by recognizing and labeling how they feel. The teacher circulating around the room doing individual check-ins with students is also a good way to gauge student needs and strengthen relationships.

The following materials provide additional insights:

- Read this article: Six Classroom Management Strategies to Prompt Social Emotional Learning.

- Here is a tool: What SEL Looks Like in the Classroom.

- Listen to this podcast on Social Emotional Learning–Classroom Must Haves. (28:23)