Chapter 8: Building and Maintaining Relationships

Over the course of our lives, we will enter into and out of many different relationships. When it comes to dating, the average person has seven relationships before getting married.1 According to a study conducted by OnePoll in conjunction with Evite, the average American has:

- Three best friends

- Five good friends

- Eight people they like but don’t spend one-on-one time with

- Fifty acquaintances

- Ninety-one social media friends2

In this chapter, we are going to discuss how we go about building and maintaining our interpersonal relationships.

8.1 The Nature of Relationships

Learning Objectives

- Understand relationship characteristics.

- Identify the purposes of relationships.

- Cognize the elements of a good relationship.

We’ve all been in a wide range of relationships in our lives. This section is going to explore relationships by examining specific relationship characteristics and the nature of significant relationships.

Relationship Characteristics

We know that all relationships are not the same. We have people in our lives that we enjoy spending time with, who like to support us, and/or assist us when needed. We will typically distance ourselves from people who do not provide positive feelings or outcomes for us. Naturally, we are not going to have the same type of relationship with each person with whom we come in contact. Thus, different relationships are made up of varying relationship characteristics. These characteristics are: duration, contact frequency, sharing, support, interaction variability, and goals.3

Some friendships last a lifetime, others last a short period. The length of any relationship is referred to as that relationship’s duration. Individuals can have friendships of varying durations. People who grew up in small towns might have had the same classmate through graduation, which by one’s average high school age, is a long duration. For example, being 18 and knowing someone 15 of those 18 years. Some people we meet in college and we will never see them again. Hence, our duration with that person is short. Duration is related to the length of your relationship with that person.

Second, contact frequency is how often you communicate with their other person. There are people in our lives we have known for years but only talk to infrequently. Typically, the more we communicate with an individual, the closer our bond becomes to the other person. Sometimes people think duration is the real test of a relationship, but it also depends on how often you communicate with the other person.

The third relationship type is based on sharing. The more we spend time with other people and interact with them, the more we are likely to share information about ourselves. This type of sharing is information that is usually our private and very intimate details of our thoughts and feelings. We typically don’t share this information with a stranger. Once we develop a sense of trust and support with this person, we can begin to share more details.

The fourth characteristic is support. Think of the people in your life and who you would be able to call in case of an emergency. The ones that come to mind are the ones you know who would be supportive of you. They would support you if you needed help, money, time, or advice. Support is another relationship type because we know that not everyone can support us in the same manner. For instance, if you need relationship advice, you would probably pick someone who has relationship knowledge and would support you in your decision. Support is so important. It was found that a major difference between married/committed couples and dating couples is that the married/committed couples were more likely to provide supportive communication behaviors to their partners more than dating couples.4

The fifth defining characteristic of relationships is the interaction variability. When we have a relationship with another person, it is not defined on your interaction with them, rather on the different types of conversations you can have with that person. When you were little, you probably knew that if you were to approach your mom, she might respond a certain way as opposed to your dad, who might respond differently. Hence, you knew that your interaction would vary. The same thing happens with your classmates because you don’t just talk about class with them. You might talk about other events on campus or social events. Therefore, our interactions with others are defined by the greater variability that we have with one person as opposed to another.

The last relationship characteristic is goals. In every relationship we enter into, we have certain expectations about that relationship. For instance, if your goal is to get closer to another person through communication, you might share your thoughts and feelings and expect the other person to do the same. If they do not, then you will probably feel like the goals in your relationship were not met because they didn’t share information. The same goes for other types of relationships. We typically expect that our significant other will be truthful, supportive, and faithful. If they break that goal, then it causes problems in the relationship and could end the relationship. Hence, in all our relationships, we have goals and expectations about how the relationship will function and operate.

Significant Relationships

Think about all the relationships that you have in your life. Which ones are the most meaningful and significant for you? Why do you consider these relationships as the most notable one(s) for you? Your parents/guardians, teachers, friends, family members, and love interests can all serve as significant relationships for you. Significant relationships have a huge impact on our communication behaviors and our interpretation of these conversations. Significant relationships impact who we are and help us grow. These relationships can serve a variety of purposes in our lives.

Purposes of Relationships

Relationships allow us to grow psychologically, emotionally, and physically and help navigate us towards better health and stability personally and professionally. In this sense, the purposes can fall under three specific categories: work, task, and social.

First, relationships can be work-related. We might have a significant work relationship that helps us advance our professional career. We might have work relationships that might support us in gaining financial benefits or better work opportunities.

Second, we might have significant relationships because it is task-related. We may have a specific task that we need to accomplish with this other person. It might be a project or a mentorship. After the task is completed, then the relationship may end. For instance, a high school coach may serve as a significant relationship. You and your coach might have a task or plan to go to the state competition. You and your coach will work on ways to help you. However, after you complete high school and your task has ended, then you might keep in contact with the coach, or you may not since your competition (task) has ended.

The last purpose is for social reasons. We may have social reasons for pursuing a relationship. These can include pleasure, inclusion, control, and/or affection. Each relationship that we have with another person has a specific purpose. We may like to spend time with a particular friend because we love talking to them. At the same time, we might like spending time with another friend because we know that they can help us become more involved with extracurricular activities.

Elements of a Good Relationship

There is much information in popular culture and in the social studies about what makes a relationship “good”. Elements of a good relationship can also vary depending on the purpose or type of relationship. Characteristics of a good life partner, might include more or different elements than a good cowoker, like intimacy. In general however, important elements might include, but are not limited to the following: trust, commitment to the relationship and a willingness to work together to maintain the relationship, mutual respect, empathy, and effective emotion management. The remaining chapters will go over more of these elements in greater detail.

Key Takeaways

- The nature of a relationship is not determined immediately; often, it evolves and is defined and redefined over time.

- Relationship characteristics include duration, contact frequency, sharing, support, interaction variability, and goals.

- A relationship can serve a work, task, or social purpose.

Exercises

- Conduct an inventory of your relationships. Think of all the people in your life and how they meet each of the relationship characteristics.

- Write a list of all the good relationships that you have with others or witnessed. What makes these relationships good? Is it similar to what we talked about in this chapter? Was anything different? Why?

- Write a hypothetical relationship article for a website. What elements make a lasting relationship? What would you write? What would you emphasize? Why? Let a friend read it and provide input.

8.2 Relationship Formation

Learning Objectives

- Understand attraction.

- Ascertain reasons for attraction.

- Realize the different types of attraction.

Have you ever wondered why people pick certain relationships over others? We can’t pick our family members, although I know someone people wish they could. We can, however, select who are friends and significant others are in our lives. Throughout our lives, we pick and select people that we build a connection to and have an attraction towards. We tend to avoid certain people who we don’t find attractive.

Understanding Attraction

Researchers have identified three primary types of attraction: physical, social, and task. Physical attraction refers to the degree to which you find another person aesthetically pleasing. What is deemed aesthetically pleasing can alter greatly from one culture to the next. We also know that pop culture can greatly define what is considered to be physically appealing from one era to the next. Think of the curvaceous ideal of Marilyn Monroe and Elizabeth Taylor in the 1950s as compared to the thin models and actresses of today, like Zendaya or Kendall Jenner. Although discussions of male physical attraction occur less often, they are equally impacted by pop culture. In the 1950s, you had popular icons like James Dean and Marlon Brando as compared to the heavily muscled men of the past decade like Dwayne “the Rock’ Johnson (People Magazine’s 2016 Sexist Man Alive designee) or Jason Momoa (voted #1 on 2019’s 100 Most Beautiful Faces List).

The second type of attraction is social attraction, or the degree to which an individual sees another person as entertaining, intriguing, and fun to be around. We all have finite sources when it comes to the amount of time we have in a given day. We prefer to socialize with people that we think are fun. These people may entertain us or they may just fascinate us. No matter the reason, we find some people more socially desirable than others. Social attraction can also be a factor of power. For example, in situations where there are kids in the “in-group” and those that are not. In this case, those that are considered popular hold more power and are perceived as being more socially desirable to associate with. This relationship becomes problematic when these individuals decide to use this social desirability as a tool or weapon against others.

The final type of attraction is task attraction, or people we are attracted to because they possess specific knowledge and/or skills that help us accomplish specific goals. The first part of this definition requires that the target of task attraction possess specific knowledge and/or skills. Maybe you have a friend who is good with computers who will always fix your computer when something goes wrong. Maybe you have a friend who is good in math and can tutor you. Of course, the purpose of these relationships is to help you accomplish your own goals. In the first case, you have the goal of not having a broken down computer. In the second case, you have the goal of passing math. This is not to say that an individual may only be viewed as task attractive, but many relationships we form are because of task attraction in our lives.

Reasons for Attraction

Now that we’ve looked at the basics of what attraction is. Let’s switch gears and talk about why we are attracted to each other. There are several reasons researchers have found for our attraction to others including proximity, physicality, perceived gain, similarities and differences, and disclosure.

Physical Proximity

When you ask some people how they met their significant other, you will often hear proximity is a factor in how they met. Perhaps, they were taking the same class or their families went to the same grocery store. These commonplaces create opportunities for others to meet and mingle. We are more likely to talk to people that we see frequently.

Physical Attractiveness

In day-to-day interactions, you are more likely to pay attention to someone you find more attractive than others. Research shows that males place more emphasis on physical attractiveness than females.5 Appearance is very important at the beginning of the relationship.

Perceived Gain

This type of relationship might appear to be like an economic model and can be explained by exchange theory.6 In other words, we will form relationships with people who can offer us rewards that outweigh the costs. Rewards are the things we want to acquire. They could be tangible (e.g., food, money, clothes) or intangible (support, admiration, status). Costs are undesirable things that we don’t want to expend a lot of energy to do. For instance, we don’t want to have to constantly nag the other person to call us or spend a lot of time arguing about past items. A good relationship will have fewer costs and more rewards. A bad relationship will have more costs and fewer rewards. Often, when people decide to stay or leave a relationship, they will consider the costs and rewards in the relationship.

Costs and rewards are not the only factors in a relationship. Partners also consider alternatives in the relationship. For instance, Becky and Alan have been together for a few years. Becky adores Alan and wants to marry him, but she feels that there are some problems in the relationship. Alan has a horrible temper; he is pessimistic; and he is critical of her. Becky has gained some weight, and Alan has said some hurtful things to her. Becky knows that every relationship will have issues. She doesn’t know whether to continue this relationship and take it further or if she should end it.

Her first alternative is called the comparison level(CL), which is the minimum standard that she is willing to tolerate. If Becky believes that it is ok for a person to say hurtful things to her or get angry, then Alan is meeting or exceeding her CL. However, if past romantic partners have never said anything hurtful towards her, then she would have a lower CL.

Becky will also consider another alternative, which is the comparison level of alternatives (CLalt), or the comparison between current relationship rewards and what she might get in another relationship. If she doesn’t want to be single, then she might have a lower CL of alternatives. If she has another potential mate who would probably treat her better, then she would have a higher level of alternatives. We use this calculation all the time in relationships. Often when people are considering the possibility to end a relationship, they will consider all alternatives rather than just focusing on costs and rewards.

Similarities and Differences

It feels comforting when someone who appears to like the same things you like also has other similarities to you. Thus, you don’t have to explain yourself or give reasons for doing things a certain way. People with similar cultural, ethnic, or religious backgrounds are typically drawn to each other for this reason. It is also known as similarity thesis. The similarity thesis basically states that we are attracted to and tend to form relationships with others who are similar to us.7 There are three reasons why similarity thesis works: validation, predictability, and affiliation. First, it is validating to know that someone likes the same things that we do. It confirms and endorses what we believe. In turn, it increases support and affection. Second, when we are similar to another person, we can make predictions about what they will like and not like. We can make better estimations and expectations about what the person will do and how they will behave. The third reason is due to the fact that we like others that are similar to us and thus they should like us because we are the same. Hence, it creates affiliation or connection with that other person.

However, there are some people who are attracted to someone completely opposite from who they are. This is where differences come into play. Differences can make a relationship stronger, especially when you have a relationship that is complementary. In complementary relationships, each person in the relationship can help satisfy the other person’s needs. For instance, one person likes to talk, and the other person likes to listen. They get along great because they can be comfortable in their communication behaviors and roles. In addition, they don’t have to argue over who will need to talk. Another example might be that one person likes to cook, and the other person likes to eat. This is a great relationship because both people are getting what they like to do, and it complements each other’s talents. Usually, friction will occur when there are differences of opinion or control issues. For example, if you have someone who loves to spend money and the other person who loves to save money, it might be very hard to decide how to handle financial issues.

Disclosure

Sometimes we form relationships we others after we have mutually disclosed something about ourselves to others. Disclosure increases liking because it creates support and trust between you and this other person. We typically don’t disclose our most intimate thoughts to a stranger. We do this behavior with people we are close to because it creates a bond with the other person.

Disclosure is not the only factor that can lead to forming relationships. Disclosure needs to be appropriate and reciprocal.8 In other words, if you provide information, it must be mutual. If you reveal too much or too little, it might be regarded as inappropriate and can create tension. Also, if you disclose information too soon or too quickly in the relationship, it can create some negative outcomes.

Key Takeaways

- We can be attracted to another person via various ways. It might be due to physical proximity, physical appearance, perceived gain, similarity/differences, and disclosure.

- The deepening of relationships can occur through disclosure and mutual trust.

Exercises

- Take a poll of the couples that you know and how they met. Which category does it fall into? Is there a difference among your couples and how they met?

- What are some ways that you could form a relationship with others? Discuss your findings with the class. How is it different/similar to what we talked about in this chapter?

8.3 Stages of Relationships

Learning Objectives

- Describe the coming together stages.

- Discern the coming apart stages.

- Realize relationship maintenance strategies.

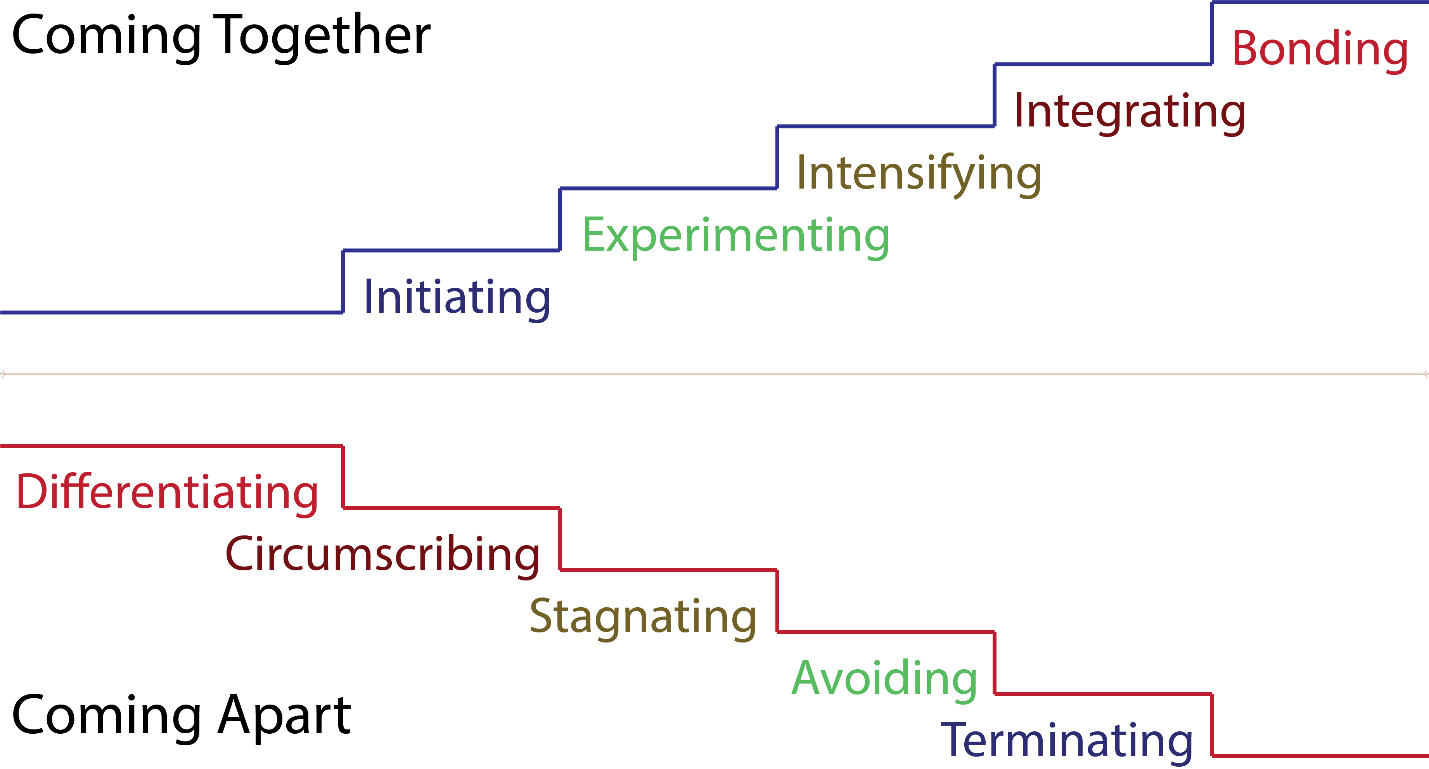

Every relationship does through various stages. Mark Knapp first introduced a series of stages that relationships can progress.9 This model was later modified by himself and coauthor Anita Vangelisti creates a model of relationships.10 They believe that we come together and we can come apart in stages. Relationships can get stronger or weaker. Most relationships go through some or all of these stages.

Coming Together

Do you remember when you first met that special someone in your life? How did your relationship start? How did you two become closer? Every relationship has to start somewhere. It begins and grows. In this section, we will learn about the coming together stages, which include: initiating, experimenting, intensifying, integrating, and then bonding.

Initiating

At the beginning of every relationship, we have to figure out if we want to put in the energy and effort to talk to the other person. If we are interested in pursuing the relationship, we have to let the other person know that we are interested in initiating a conversation.

Communication at this initiating stage is very brief. We might say hello and introduce yourself to the other person. You might smile or wink to let the other person know you are interested in making conversation with him or her. The conversation is very superficial and not very personal at all. At this stage, we are primarily interested in making contact.

There are different types of initiation. Sustaining is trying to continue the conversation. Networking is where you contact others for a relationship. Offering is where you present your interest in some manner. Approaching is where you directly make contact with the other person. We can begin a relationship in a variety of different ways.

Experimenting

After we have initiated communication with the other person, we go to the next stage, which is experimenting. At this stage, you are trying to figure out if you want to continue the relationship further. We are trying to learn more about the other person.

At this stage, interactions are very casual. You are looking for common ground or similarities that you share. You might talk about your favorite things, such as colors, sports, teachers, etc. Just like the name of the stage, we are experimenting and trying to figure out if we should move towards the next stage or not.

Intensifying

After we talk with the other person and decide that this is someone we want to have a relationship with, we enter the intensifying stage. We share more intimate and/or personal information about ourselves with that person. Conversations become more serious, and our interactions are more meaningful. At this stage, you might stop saying “I” and say “we.” So, in the past, you might have said to your partner, “I am having a night out with my friends.” It changes to “we are going to with my friends tonight.” We are becoming more serious about the relationship.

Integrating

The integrating stage is where two people truly become a couple and mix into each others lives. Before they might have been dating or enjoying each other’s company, but in this stage, they are letting each other know and usually people around them that they are exclusively dating each other. This is where you might invite them to more personal situations. You introduce this person to more friend groups or work colleagues. You might give them the spare key to your apartment or introduce them to your family. The expectations in the relationship are higher than they were before. Your knowledge of your partner has increased. The amount of time that you spend with each other is greater.

Bonding

The next stage is the bonding stage, where two people usually agree to their commitment to each other for the foreseeable future. This often involves a formal acknowledgement and often a traditional ritual, such as an engagement. Weddings and commitment ceremonies are the demonstration of couples exhibiting publicly their dedication to this bonding stage.

Coming Apart

Some couples can stay in committed and wonderful relationships. However, there are some couples that after bonding, things seem to fall apart. No matter how hard they try to stay together, there is tension and disagreement. These couples go through a coming apart process that involves: differentiating, circumscribing, stagnating, avoiding, and terminating.

Differentiating

The differentiating stage is where both people are trying to figure out their own identities. Thus, instead of trying to say “we,” the partners will question “how am I different?” In this stage, differences are emphasized and similarities are overlooked.

As the partners differentiate themselves from each other, they tend to engage in more disagreements. The couples will tend to change their pronoun use from “our kitchen” becomes “my kitchen” or “our child” becomes “my child,” depending on what they want to emphasize.

Initially, in the relationship, we tend to focus on what we have in common with each other. After we have bonded, we are trying to deal with balancing our independence from the other person. If this cannot be resolved, then tensions will emerge, and it usually signals that your relationship is coming apart.

Circumscribing

The circumscribing stage is where the partners tend to limit their interactions with each other. Communication will lessen in quality and quantity. Partners try to figure out what they can and can’t talk about with each other so that they will not argue.

Partners might not spend as much time with each other at this stage. There are fewer physical displays of affection, as well. Intimacy decreases between the partners. The partners no longer desire to be with each other and only communicate when necessary.

Stagnating

The next stage is stagnating, which means the relationship is not improving or growing. The relationship is motionless or stagnating. Partners do not try to communicate with each other. When communication does occur, it is usually restrained and often awkward. The partners live with each other physically but not emotionally. They tend to distance themselves from the other person. Their enthusiasm for the relationship is gone. What used to be fun and exciting for the couple is now a chore.

Avoiding

The avoiding stage is where both people avoid each other altogether. They would rather stay away from each other than communicate. At this stage, the partners do not want to see each other or speak to each other. Sometimes, the partners will think that they don’t want to be in the relationship any longer.

Terminating

The terminating stage is where the parties decide to end or terminate the relationship. It is never easy to end a relationship. A variety of factors can determine whether to cease or continue the relationship. Time is a factor. Couples have to decide to end it gradually or quickly. Couples also have to determine what happens after the termination of the relationship. Besides, partners have to choose how they want to end the relationship. For instance, some people end the relationship via electronic means (e.g., text message, email, Facebook posting) or via face-to-face. There are ways to terminate a relationship that are more appropriate than others. There are also times when other factors, such as one’s safely, needs to be taken into consideration as well. We’ll discuss more of the “dark sides” of communication in chapter 14.

Final Thoughts on Coming Together

Not every relationship will go through each of the ten stages. Several relationships do not go past the experimenting stage. Some remain happy at the intensifying or bonding stage. When both people agree that their relationship is satisfying and each person has their needs met, then stabilization occurs. Some relationships go out of order as well. For instance, in some arranged marriages, the bonding occurs first, and then the couple goes through various phases. Some people jump from one stage into another. When partners disagree about what is optimal stabilization, then disagreements and tensions will occur.

In today’s world, romantic relationships can take on a variety of different meanings and expectations. For instance, “hooking up” or having “friends with benefits” are terms that people might use to describe the status of their relationship. Many people might engage in a variety of relationships but not necessarily get married. We know that relationships vary from couple to couple. No matter what the relationship type, couples decided to come together or come apart.

Relationship Maintenance

You may have heard that relationships are hard work. Relationships need maintenance and care. Just like your body needs food and your car needs gasoline to run, your relationships need attention as well. When people are in a relationship with each other, what makes a difference to keep people together is how they feel when they are with each other. Maintenance can make a relationship more satisfying and successful.

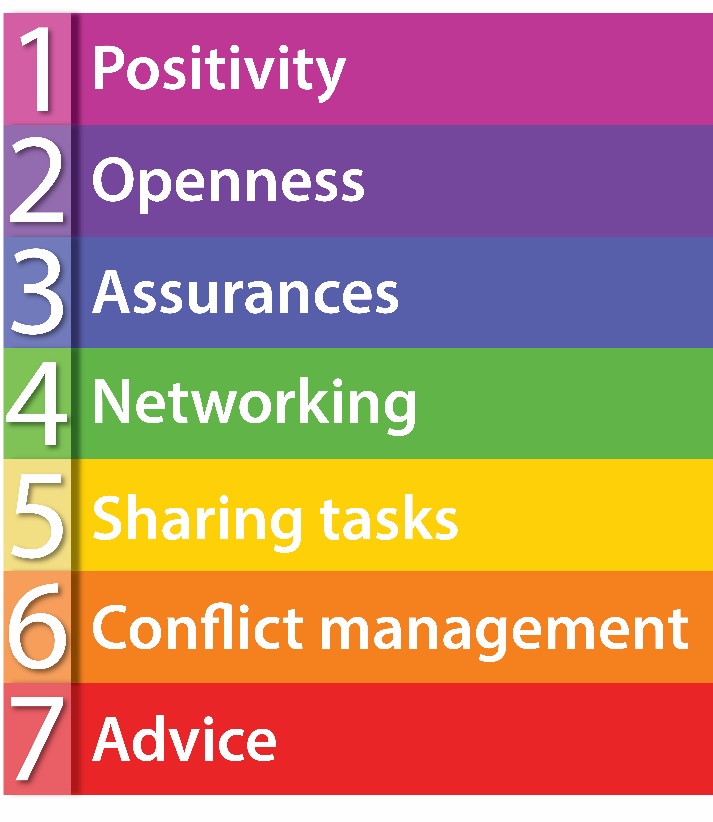

Daniel Canary and Laura Stafford stated that “most people desire long-term, stable, and satisfying relationships.”11 To keep a satisfying relationship, individuals must utilize relationship maintenance behaviors. They believed that if individuals do not maintain their relationships, the relationships will weaken and/or end. “It is naïve to assume that relationships simply stay together until they fall apart or that they happen to stay together.”12

Joe Ayres studied how individuals maintain their interpersonal relationships.13 Through factor analysis, he identified three types of strategies. First, avoidance strategies are used to evade communication that might threaten the relationship. Second, balance strategies are used to maintain equality in the relationship so that partners do not feel underbenefited or overbenefited from being in the relationship. Third, direct strategies are used to evaluate and remind the partner of relationship objectives. It is worth noting that Joe Ayers found that relationship intent had a major influence on the perceptions of the relationship partners. If partners wanted to stay together, they would make more of an effort to employ maintenance strategies than deterioration strategies.

Laura Stafford and Daniel Canary (1991) found five key relationship maintenance behaviors. First, positivity is a relational maintenance factor used by communicating with their partners in a happy and supportive manner. Second, openness occurs when partners focus their communication on the relationship. Third, assurances are words that emphasize the partners’ commitment to the duration of the relationship. Fourth, networking is communicating with family and friends. Lastly, sharing tasks is doing work or household tasks. Later, Canary and his colleagues found two more relationship maintenance behaviors: conflict management and advice.14

Additionally, Canary and Stafford also posited four propositions that serve as a conceptual framework for relationship maintenance research.15 The first proposition is that relationships will worsen if they are not maintained. The second proposition is that both partners must feel that there are equal benefits and sacrifices in the relationship for it to sustain. The third proposition states that maintenance behaviors depend on the type of relationship. The fourth proposition is that relationship maintenance behaviors can be used alone or as a mixture to affect perceptions of the relationship. Overall, these propositions illustrate the importance and effect that relationship maintenance behaviors can have on relationships.

Relationship maintenance is the stabilization point between relationship initiation and potential relationship destruction.16 There are two elements to relationship maintenance. First, strategic plans are intentional behaviors and actions used to maintain the relationship. Second, everyday interactions help to sustain the relationship. Most importantly, talk is the most important element in relationship maintenance.17

Key Takeaways

- The coming together stages include: initiating, experimenting, intensifying, integrating, and bonding.

- The coming apart stages include: differentiating, circumscribing, stagnating, avoiding, and terminating.

- Relationship maintenance strategies include positivity, openness, assurances, sharing tasks, conflict management, social networks, and advice.

Exercises

- Find Internet clips that illustrate each of the coming together/coming apart stages. Show them to your class. Do you agree/disagree?

- Do a self-analysis of a relationship that you have been involved with or have witnessed. How did the two people come together and come apart? Did they go through all the stages? Why/why not?

- Write down an example of each the relationship maintenance strategies. Then, rank order in terms of importance to you. Why did you rank them the way that you did? Find a peer and compare your answers.

8.4 Communication in Relationships*

Learning Objectives

- Analyze relationship dialectics.

- Explain varied ways of managing dialectical tensions

Relationship Dialectics

We know that all relationships go through change. The changes in a relationship are often dependent on communication. When a relationship starts, there is a lot of positive and ample communication between the parties. However, sometimes couples go through a redundant problem, and it is important to learn how to deal with this problem. Partners can’t always know what their significant other desires or needs from them.

Dialectics had been a concept known well to many scholars for many years. They are simply the pushes and pulls that can be found every day in relationships of all types. Conversation involves people who must learn to adapt to each other while still maintaining their individuality (Baxter, 2004). The theory emphasizes interactions allowing for more flexibility to explain how couples maintain a satisfactory, cohesive union. This perspective views relationships as simply managing the tensions that arise because they cannot be fully resolved. The management of the tensions is usually based on past experiences; what worked for a person in the past will be what they decide to use in the future. These tensions are both contradictory and interdependent because without one, the other is not understood. Leslie A. Baxter, the scholar who developed this theory, pulled from as many outside sources as she could to better understand the phenomenon of dialectical tensions within relationships.

Dialectical tension is how individuals deal with struggles in their relationships. There are opposing forces or struggles that couples have to deal with. It is baseeslie Baxter and Barbara Montgomery’s Relational Dialectics Theory in 1996.

Below are some different relational dialectics (Baxter, 1996).

Autonomy-Connection (sometimes labeled separation-integration)

This is a need to have a close connection with others as well as our need to have our own space and identity. We may miss our romantic partners when they are away but simultaneously enjoy and cherish that alone time. When you first enter a relationship, you may want to be around the other person as much as possible. As the relationship grows, you likely begin to desire fulfilling your need for autonomy, or alone time. In every relationship, each person must balance how much time to spend with the other, versus how much time to spend alone.

Predictability–Novelty

We desire predictability as well as spontaneity in our relationships. In our relationships, we take comfort in a certain level of routine as a way of knowing what we can count on the other person in the relationship. Such predictability provides a sense of comfort and security. However, it requires balance with novelty to avoid boredom. An example of balance might be friends who get together every Saturday for brunch but make a commitment to always try new restaurants each week.

Openness–Closedness

This dialectic refers to the desire to be open and honest with others while at the same time not wanting to reveal everything about yourself to someone else. One’s desire for privacy does not mean they are shutting out others. It is a normal human need. We may disclose different levels of information at different stages of our relationship. We tend to disclose the most personal information to those with whom we have the closest relationships. You may remember that disclosure depends on the trust level of the other person. However, even the closest relationships may not know everything about us (think about the Johari Window).

Similarity-Difference

This tension deals with self vs. others. Some couples are very similar in their thinking and beliefs. This is good because it makes communication easier and conflict resolution smoother. Yet, if partners are too similar, then they may not grow. Differences can create stimulation that helps people to grow and learn new things. While research indicates we all like to engage in relationships with those similar to us, we may have different needs for similarity and difference.

Ideal-Real

Couples will perceive some things as good and some things as bad within the relationship. Their perceptions of what is ideal may interfere with or inhibit perceptions of what is real. One common example is perceiving relationships depicted on social media as the goal for our own relationships, not taking into account that what is posted on social media is only a small percentage of those people’s lives. This ideal desire can interfere with what is real within the relationship and cause conflict.

Managing Dialectics

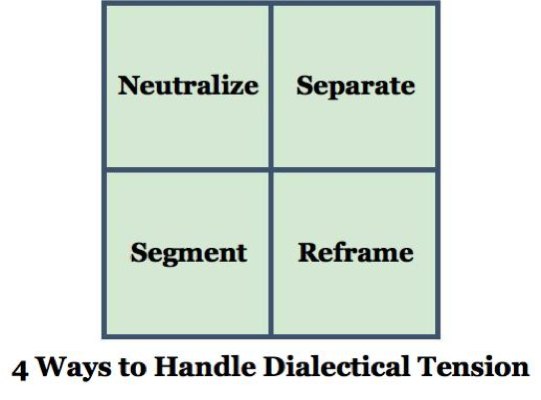

Other ways of managing dialectical tensions may be:

• Denial is where we lean toward one end of the dialectic and ignore that the other side exists.

• Disorientation is where we feel overwhelmed and we may fight, freeze, or leave.

• Alternation is where we choose one end on different occasions based on contextual elements of the situation.

• Recalibration is reframing the situation or perspective. Think perception checking and working out alternatives to current perspectives.

• Segmentation is where we compartmentalize different areas. We may choose one side of a dialectic in our communication and one side of a dialectic in our time spent together.

• Balance is where we manage and compromise our needs.

• Integration is blending different perspectives.

• Reaffirmation is having the knowledge & accepting our differences.

Understanding our dialectical perspectives can help us to communicate our needs in relationships. Not everyone deals with dialectical tensions in the same way and there is no perfect way to balance dialectics. Some people will use a certain strategy during specific situations, and others will use the same strategy every time there is tension. You have to decide what is best for your relationship based on the situation.

*This section taken directly from Maricopa Community College’s openly licensed OER, Exploring Relationship Dynamics produced through the Maricopa Open Digital Press. Their text was a cloned and adapted edition of Communication in the Real World: An Introduction to Communication Studies produced by the University of Minnesota Libraries Publishing through the eLearning Support Initiative. Resource for this text was imported in March or 2023 directly from the OER site, Chapter 6.6 Relationship Dialectics.

Key Takeaways

- Relationship dialectics are tensions that happen in a relationship.

- Understanding our dialectical perspectives can help us to communicate more effectively in our relationships.

Exercise

- Consider three different issues that you might be dealing in a relationship that you have with another person. What are the relationship dialectic tensions? How are you handling these tensions? Identify what strategy you are using to deal with this tension. Why?

8.5 Dating Relationships

Learning Objectives

- Learn the 5 supracategories of dating.

- Analyze John Lee’s 6 love styles.

We talk of dating as a single construct a lot of the time without really thinking through how dating has changed over time. In the twentieth century alone, we saw dating go from a highly formalized structure involving calling cards and sitting rooms; to drive-in movies in the back seat of a car; to cyberdating with people we’ve never met.27 The 21st Century has already changed how people date through social networking sites and geolocation dating apps on smartphones. Dating is not a single thing, and dating has definitely changed with the times.

Supracategories of Dating

So, with all of this change, how does one even begin to know if someone’s on a date in the first place. Thankfully Paul Mongeau, Janet Jacobsen, and Carolyn Donnerstein have attempted to answer this question for us.28 The researchers found that there are five what they called “supracategories” that help define the term “date”: communication expectations, date goals, date elements, dyadic interactions, and feelings.

- First, dating involves specific communication expectations. For example, people expect that there will be a certain level of self-disclosure on a date. Furthermore, people expect that their dating partner will be polite, relaxed, and social.

- Second, dating involves specific date goals, or people on dates have specific goals (e.g., future romantic relationships, reduce uncertainty, have fun, etc.).

- Third, there are specific date elements. For example, someone has to initiate the date; we get ready for a date, we know when the date has started and stopped, there are activities that constitute the date, etc…

- Fourth, dates are dyadic, or dating is a couple-based activity. Now, this doesn’t necessarily take into account the idea of “group dates,” but even on a group date there are dyadic couples that are involved in the date itself.

- Lastly, dates involve feelings. “These feelings range from affection (nonromantic feelings or behaviors), attraction (physical and/or emotional attraction toward the partner), to romantic (dates have romantic overtones).”29

All of us are going to spend a portion of our lives in some kind of dating relationship. Whether we are initiating dates, participating in a date, or terminating a dating relationship, we spend a great deal of time dating. It can be both an exciting and awkward time as there are many unknown variables that can affect the outcome. Because there are different “supracategories” that come into play, some dates lead to more dates, while others are a one-and-done deal. Life for singles in the dating scene also changes with time. Match.com publishes an annual study examining singles in the United States (https://www.singlesinamerica.com/). According to their latest publishing on 2022 research,30 they’ve discovered, “What’s hot (conscious dating, mental health, sex positivity), what’s not (superficiality, sex in the metaverse, political misalignment), and why acceptance, inclusivity, and open-mindedness have never been sexier.”

Superficial is super dated. Now more than ever, singles are invested in conscious dating: Looking beyond just physical attraction to use dating as a way to learn about themselves (who they are, what they need, and their behavioral patterns throughout the process). Age, distance, and other surface-level attributes are taking a back seat to good, old fashioned authenticity. We’ve heard it loud and clear: Singles are dating with intention — and they’re seeking someone with mindfulness to match.

Here’s just a few of their findings:

- 84% of singles say they prefer casual dates over stuffy wine and dines.

- 49% have fallen in love with someone they weren’t initially attracted to (up from 38% in the last decade).

- 70% are open to finding a relationship today, with 80% indicating they’d like to find something that lasts.

- 53% say they’d start a relationship with someone who lives more than 3 hours away (compared to only 35% last year).

- 70% report sex improves their mental and physical health.

- 38% of singles say they feel more sexually empowered this year.

- 56% of singles overall want a partner who supports people’s freedom to identify as something other than their biological sex.

- 41% of Gen Z and 31% of Millennials are open to dating someone who is transgender.

- 56% of Gen Z and 42% of Millennials are open to dating someone who is pansexual.

- 44 of Gen Z and 31% of Millennials are open to dating someone who is gender non-binary.

- 58% say it’s now more important than ever to know a partner’s political views.

- 28% don’t want a partner who isn’t registered to vote.

- 22% say it’s a deal breaker if their date didn’t vote in the last election.

- 30% are now more open to doing free activities on a date.

- 26% are more open to eating a home-cooked meal vs. eating at a restaurant.

- 96% feel that having similar attitudes about debt and spending is an important partner trait, which is at an all time high over the last decade.

- 87% of singles say it’s important for both partners to prioritize mental health.

Singles in America is funded by Match and conducted by Dynata in association with renowned anthropologist Dr. Helen Fisher and evolutionary biologist Dr. Justin Garcia of The Kinsey Institute at Indiana University.

The 2022 study is based on the attitudes and behaviors taken from a demographically representative sample of 5,000 U.S. singles between the ages of 18 to 98. Generations are defined as: Gen Z (18-25), Millennials (26-41), Gen X (42-57), and Boomers (58-76). Singles in America remains the most comprehensive annual scientific survey of single Americans.

More information and other statistics can be found on their site Singles in America.

Keep in mind that although interesting, we also have to realize the study might be limited. Even so, it still presents an image of the ever-changing scope of the dating scene. We often think of dating as something that occurs purely among young people before they get married, but we know people in all age groups date and romantic relationships come in all shapes and forms. In fact, we’ve been conditioned since we were very young to date. We’ve listened to adults tell stories of dating. We’ve watched dating as it is fictionalized on television and in movies. Dating narratives surround us, and all of these narratives help create what’s called “dating scripts” of what we expect is going to happen.

Although dating may feel like you’re making it up as you go along, you already possess a treasure trove of information about how dating works. Thankfully, because we have these cultural images of dating presented to us, we also know that our dating partner (as long as they are from a similar culture, background, and value set) will have similar dating scripts. These scripts can be challenging though as they can also contain stereotypes or expectation bias. For example, in a heterosexual date, does the guy have to pay? Is that sexist to expect? Are there privileges a heterosexist couple experiences that non-heterosexual couples don’t in choosing where to go and what to do on a first date based on safety issues or being able to freely have some initial conversations in a public setting? How does this change when at the public-display of affection stage? Are there expectations for alcohol or physical contact that could violate someone’s religious values and could sharing those values be a concern for scaring someone off? Dating isn’t always easy, which is why communication is so important. It’s not just about you, it’s about the other person, the place you go, what you do, and how you do it that need to be continually assessed and done so mindfully.

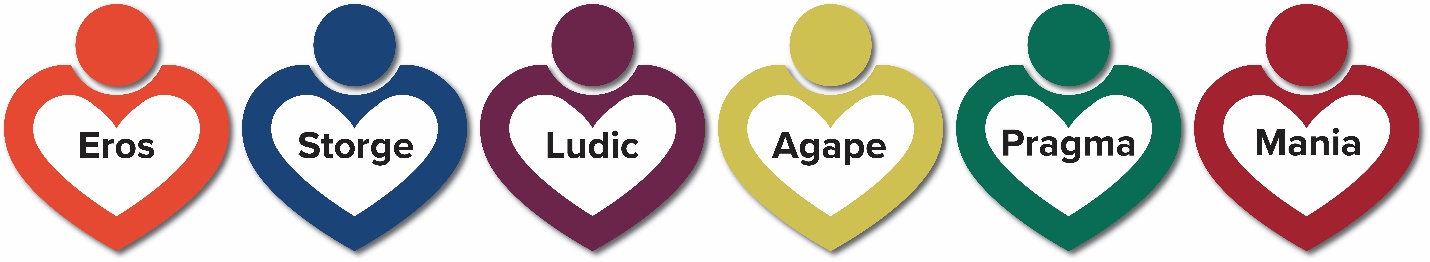

Love Styles

An individual’s love style is considered to be an attitude and describes how love is perceived.42 Attitudes toward love and perceptions of love may change throughout an individual’s life. Traditional-aged college students may perceive love very differently from their parents or guardians because most often, each are in very different stages of life. Traditional college students are often living among people their age who are more than likely single or unmarried. These two factors mean that there are more prospects for dating, and this may lead the college student to conclude that dating any number of these prospects is necessary or even perceive that “hooking up” with multiple prospects is acceptable. In contrast, individuals with children who are financially tied may view romantic relationships as partnerships in which goal achievement (pay off the house, send kids to college, pay off debt, etc.) Three are identified as is as important as romance. These differences in perceptions of love can be explored through John Lee’s love typology in which he discusses six love styles: eros, storge, ludus, agape, pragma, and mania (Figure 8.3).43 These revolve around different levels of passion, companionship, and respect. Three are primary types (Eros, Storge, and Ludus) and three are secondary types (Agape, Pragma, Mania). Let’s look at all six.

Eros

Eros is a romantic, passionate type of love. It emphasizes physical beauty, immediate attraction, emotional intensity, and strong commitment. Eros love involves the early initiation of sexual intimacy and consecutive monogamous relationships.

Storge

Storge love develops slowly out of friendship where stability and psychological closeness are valued along with commitment, which leads to enduring love. Intimacy and feeling close to one’s partner is important but extreme passion and intense emotions are not valued as they are in the Eros love style. This individual wants a best-friend in their partner.

Ludic/Ludus

Ludic lovers view love as a game, and playing this game with multiple partners is perceived to be acceptable by individuals with this love style. As such, this type of lover believes that deception and manipulation are acceptable. Individuals with this love style have a low tolerance for commitment, jealousy, and strong emotional attachment.

Agape

In contrast, agape love involves altruism, empathy, and other-centered love. This love style approaches relationships in a non-demanding style with gentle caring and tolerance for others. It’s an all-giving, selfless type of love.

Pragma

Pragma love is known as practical love involving logic and reason. This person might have a “shopping list” of what they expect in a “good” partner. Arranged marriages were often arranged for functional purposes. Kings and Queens of different countries often married to form alliances. This love style may seek out a romantic partner for financial stability, ability to parent, or simple companionship.

Mania

Mania is the final love style characterized by dependence, uncertainty, jealousy, and emotional upheaval. This type of love is insecure and needs constant reassurance. In addition, this person can be very possessive of their partners.

These love styles should not be considered to be mutually independent. An individual may approach love from a pragmatic stance and have found love that provides financial stability. However, they still feel insecure (representative of mania) about whether their romantic partner will remain with them, thus ensuring continued financial stability. It is important to remember that individuals engage in each of these love styles, and it is simply a matter of how much of each love style a person possesses.

Key Takeaways

- Dating isn’t necessarily easy and can be influenced over time.

- The five supracategories surrounding dating include: communication expectations, date goals, date elements, dyadic interactions, and feelings.

- The types of love are Eros, Storge, Ludus, Agape, Pragma, and Mania which all vary in different levels of passion, companionship, and respect.

- Each love style can be found in all individuals, but some love styles are more prominent than others and might change for the individual depending on their life stage.

Exercises

- List the physical features you find attractive. List the personality factors you find attractive. Would you have a romantic relationship with someone who possessed the personality characteristics you find attractive, but not the physical characteristics? Why or why not? Now, consider whether you would have a romantic relationship with someone physically attractive, but did not possess the personality characteristics you find attractive. Would you have a romantic relationship with this individual? Why or why not?

- List and define each love style. List the love style of each of your parents and grandparents.

- Describe your love style and what influential factors contributed to its development.

8.6 Improving Relationship Communication

Learning Objectives

- Understand that communication is a life-long skill.

- Understand that communication is a life-long practice.

Improving Communication Skills

Many popular guides to enhancing communication skills place particular emphasis on exploring your own needs, desires, and motives in the relationship. Some of the goals you have in a relationship may be subconscious. By becoming more aware of these goals, and what you want to achieve in a relationship, you can identify areas of the relationship that you would like to improve and generate ideas for making these changes.

Because people in relationships are interconnected and interdependent, it takes people willing to be open about their needs and relationship goals and willing to work on improving communication and, hence, the relationship in general.

As discussed previously, clear communication is necessary to give and receive information. Words have multiple denotations and connotations, and word choice is critical when you communicate about areas of your relationship that are not satisfying. Asking for and providing clarification and sending explicit messages, obtaining feedback to be sure that you are understood, and listening carefully to the feedback are all important components in effective communication. Finally, when you communicate, remember that everyone wants to be heard, to feel valued, to know that they matter, and to be assured that their ideas are important.

By taking this course you are putting yourself on a better path for improving your communication skills. There is always more to learn and work on in this regard. Even the greatest communicators have ways they can improve. We can’t cover everything in one chapter, one textbook, one course, or even with a Communication degree. It’s a life-long skill, one that is constantly needing study, mindful reflection, and mindful practice.

Key Takeaways

- By becoming more aware of your goals and open to talk about the other person’s needs, you can improve your communication.

- Communication is a life-long skill.

- Communication is a life-long practice.

Exercises

- Reflect on the strengths and weaknesses in your current or past romantic relationship. How did each category affect your relationship? What steps can you take to turn your weaknesses into relationship strengths?

- Describe the communication styles of a couple you would describe as being in a strong relationship? What about that relationship makes them classify them as “strong”? What type of examples can you come up with for rationale?

Key Terms

agape

Selfless love in which the needs of others are the priority.

attraction

Interest in another person and a desire to get to know him or her better.

avoiding

The stage of coming apart where you are creating distance from your partner.

bonding

The stage of coming together where you make a public announcement that your relationship exists.

circumscribing

The stage of coming apart where communication decreases. There are more arguments, working late, and there is less intimacy.

CL

Minimum standard of what is acceptable.

CL of alternatives

Comparison of what is happening in the relationship and what could be gained in another relationship.

compatible

Able to exist together harmoniously.

complementary

When one person can fulfill the other person’s needs.

contact frequency

This is how often you communicate with another person.

content level

Information that is communicated through the denotative and literal meanings of words.

demonstrative

Showing affection by touching or hugging other people.

differentiating

The stage of coming apart where both people are trying to figure out their own identities.

duration

The legnth of time of your relationship.

empathy

The ability to identify with and to understand how another person feels.

eros

Romantic love involving serial monogamous relationships.

experimenting

The stage of coming together; “small talk” occurs at this stage and you are searching for commonalities.

goals

Expectations about how the relationship will function.

hedge

To use words or phrases that weaken the certainty of a statement.

initiating

The stage of coming together where a person is interested in making contact and it is brief.

instrumental

Roles that are focused on being task-oriented.

Integrating

This is the stage of coming together where you take on an identity as a social unit or give up characteristics of your old self.

intensifying

The stage of coming together where two people truly become a couple.

interaction variability

The ability to talk about various topics.

interdependent

A relationship in which people need each other or depend on each other in some way, and the actions of one person affect the other.

intimacy

Close and deeply personal contact with another person.

love

Love is a multidimensional concept that can include several different orientations toward the loved person such as romantic love (attraction based on physical beauty or handsomeness), best friend love, passionate love, unrequited love (love that is not returned), and companionate love (affectionate love and tenderness between people).

love style

Love style is considered an attitude that influences an individual’s perception of love.

ludus

Love in which games are played. Lying and deceit are acceptable.

mania

Obsessive love that requires constant reassurance.

physical attraction

The degree to which one person finds another person aesthetically pleasing.

platonic

A close relationship that is not physical.

pragma

Love involving logic and reason.

relationship

A connection, association, or attachment that people have with each other.

relationship dialectic

Tensions in a relationship where individuals need to deal with integration vs. separation, expression vs. privacy, and stability vs. change.

relationship level

The type of relationship between people evidenced as through their communication.

relationship maintenance

Strategies to help your relationship be successful and satisfying.

romantic relationships

Romantic relationships involve a bond of affection with a specific partner that researchers believe involves several psychological features: a desire for emotional closeness and union with the partner, caregiving, emotional dependency on the relationship and the partner, a separation anxiety when the other person is not there, and a willingness to sacrifice for the other love.

self-disclosure

The process of sharing information with another person.

sharing

The process of revealing and disclosing information about yourself with another.

social attraction

The degree to which an individual sees another person as entertaining, intriguing, and fun to be around.

stagnating

The stage of coming apart where you are behaving in old familiar ways without much feeling. In other words, there is lost enthusiasm for old familiar things.

storge

Love that develops slowly out of friendship.

support

The ability to provide assistance, aid, or comfort to another.

symmetrical relationship

A relationship between people who see themselves as equals.

task attraction

The degree to which an individual is attracted to another person because they possess specific knowledge and/or skills that help that individual accomplish specific goals.

terminating

This is a summary of where the relationship has gone wrong and a desire to quit. It usually depends on: problems (sudden/gradual); negotiations to end (short/long); the outcome (end/continue in another form).

undifferentiated

A person who does not possess either masculine or feminine characteristics.

The length of time of your relationship.

This is how often you communicate with another person.

The process of revealing and disclosing information about yourself with another.

The ability to provide assistance, aid, or comfort to another.

The ability to talk about various topics.

Expectations about how the relationship will function.

The degree to which one person finds another person aesthetically pleasing.

The degree to which an individual sees another person as entertaining, intriguing, and fun to be around.

The degree to which an individual is attracted to another person because they possess specific knowledge and/or skills that help that individual accomplish specific goals.

Minimum standard of what is acceptable.

Comparison of what is happening in the relationship and what could be gained in another relationship.

When romantic workplace relationships occur because people find coworkers have similar personalities, interests, backgrounds, desires, needs, goals, etc.…

When one person can fulfill the other person’s needs.

The stage of coming together where a person is interested in making contact and it is brief.

The stage of coming together “Small talk” occurs at this stage and you are searching for commonalities.

The stage of coming together where two people truly become a couple.

This is the stage of coming together where you take on an identity as a social unit or give up characteristics of your old self.

The stage of coming together where you make a public announcement that your relationship exists.

The stage of coming apart where both people are trying to figure out their own identities.

The stage of coming apart where communication decreases. There are more arguments, working late, and there is less intimacy.

The stage of coming apart where you are behaving in old familiar ways without much feeling. In other words, there is lost enthusiasm for old familiar things.

The stage of coming apart where you are creating distance from your partner.

This is a summary of where the relationship has gone wrong and a desire to quit. It usually depends on: problems (sudden/gradual); negotiations to end (short/long); the outcome (end/continue in another form).

Strategies to help your relationship be successful and satisfying.

Step-by-step expectations for each individual party of how the date is expected to go which is often formed through pop-culture, past experience, and other heard narratives

Romantic love involving serial monogamous relationships.

Love that develops slowly out of friendship.

Love in which games are played. Lying and deceit are acceptable.

Selfless love in which the needs of others are the priority.

Love involving logic and reason.

Obsessive love that requires constant reassurance.