Chapter 12: Interpersonal Communication in Mediated Contexts

In today’s world, we all spend a lot of time on various devices designed to make our lives easier. From smartphones to social media, we are all in constant contact with family, friends, coworkers, etc. Since the earliest days of communication technologies, we have always used these technologies to interact with one another. This chapter is going to examine how technology helps mediated our interpersonal relationships.

12.1 Technology and Communication

Learning Objectives

- Explain the history of computer-mediated communication.

- Recognize some of the important figures in the creation of the Internet, the World Wide Web, and computer-mediated communication.

Since the Internet’s creation in 1969, public access to the Internet and the creation of the World Wide Web (www) in 1991, and the proliferation of internet service providers through the late 1990s, the technology that shapes your life today and tomorrow is still relatively new. Here are some relatively recent landmarks in social media sites, technology, and apps: LinkedIn (2003), iTunes (2003), Facebook (2004), YouTube (2005), Twitter (2006), iPhone (2007), Drop Box (2008), Google Docs (2009), Kickstarter (2010), Google+ (2011), Google Glass (2012), Oculus Rift (2013), iWatch (2014). As you can imagine, just limiting this list is hard. Some of these products you’re probably very familiar with while others may be new to you altogether.

From Math to Punch Cards

Before we get started, it’s essential to understand the evolution of what we call computer-mediated communication or CMC. Now some scholars have adopted the broader term “communication and technology” in recent years. Still, we don’t think this is necessary because a computer of some kind is always at the center of these communicative interactions.

So, our first question should be, what is a computer. In its earliest use, “computers” were people who performed massive amounts of calculations by hand or using a tool like an abacus or slide rule (Figure 12.1). As you can imagine, this process wasn’t exactly efficient and took a lot of human resources. The 2016 movie Hidden Figures shows the true story of a group of African American computers who created the calculations to land the first Astronaut on the Moon.

Figure 12.1 Abacus and Slide Rule

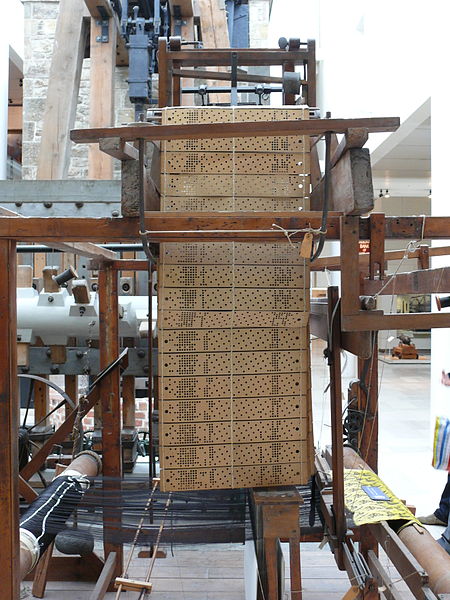

The first mechanical ancestor of the computer we have today was created in 1801 by a Frenchman named Joseph Marie Jacquard, who created a loom that used punched wooden cards to weave fabric (Figure 12.2). The idea of “punch cards” would be the basis of many generations of computers until the 1960s. Of course, the punch cards went from being wood cards to cardboard or cardstock throughout its history. Some of the earliest statistical research in the field of communication was conducted using punchcards. As you can imagine, a lot of very important people worked from the early 1800s to the 1960s to advance the modern computer. Many wonderful books can introduce you to the full history of how we came to the modern personal computer.1

The 1970s saw the start of the explosion of the personal computer. In 1981, IBM released the Acorn, which runs on Microsoft DOS, which is followed up by Apple’s Lisa in 1983, which had a graphic user interface. From that point until now, Microsoft and Apple (Macintosh) have cornered the market on personal computers.

Getting Computers to Interact

One thing that we have seen is that with each new computer development, we’ve seen new technologies emerge that have helped us communicate and interact. One significant development in 1969 changed the direction of humanity forever. Starting in 1965, researchers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology were able to get two computers to “talk” to each other. Of course, it’s one thing to get two computers side-by-side to talk to each other, but could they get computers at a distance to talk to each other (in a manner similar to how people use telephones to communicate at a distance)?

Researchers at both the UCLA and Stanford, with grant funding from the U.S. Defense Department’s Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA), set out to get computers at a distance to talk to each other. In 1969, UCLA student Charley Kline attempted the first computer-to-computer communication over a distance from his terminal in Los Angeles to a terminal at Stanford. The first message to be sent was to be a simple one, “login.” The letter “l” was sent, then the letter “o,” and then the system crashed. So, the first message ever sent over what would become the Internet was “lo.” An hour later, Kline got the system up and running again, and the full word “login” was sent.

In the earliest years of the Internet, most people didn’t know it existed. The Internet was primarily a tool for the Department of Defense to allow researchers at multiple sites across the country to work on defense projects. It was called the Advanced Research Projects Agency Network (ARPANET). In 1973, the University College of London (England) and the Royal Radar Establishment (Norway) connected to ARPANET, and the term “Internet” was born. A year later, in 1974, a commercialized version of ARPANET called Telenet became the first internet service provider (ISP).

Allowing People to Communicate

The early Internet was not exactly designed for your regular user, so it took quite a bit of skill and “know how” to use it and find things. Of course, while the Internet was developing, so was its capability for allowing people to communicate and interact with one another. In 1971, Ray Tomlinson was working on two programs that could be used over ARPANET: SNDMSG and READMAIL. From his lab at MIT, Tomlison sent a message from one computer to another computer sitting right next to it, but he sent the message through ARPANET, creating the first electronic email. Tomlison also forever changed our lives by introducing the “@” symbol as the tool the Internet uses when handling sending and receiving of messages.

In addition to email, another breakthrough in computer-mediated communication was the development of Internet forums or message/bulletin boards, which were online discussion sites where people can hold conversations in the form of posted messages. Steve Walker created an early message system for ARPANET. The primary message list for professionals was MsgGroup. The number one unofficial message list was SF-Lovers, a science fiction list. As you can see, from the earliest days of the Internet, people were using the Internet as a tool to communicate and interact with people who had similar interests.

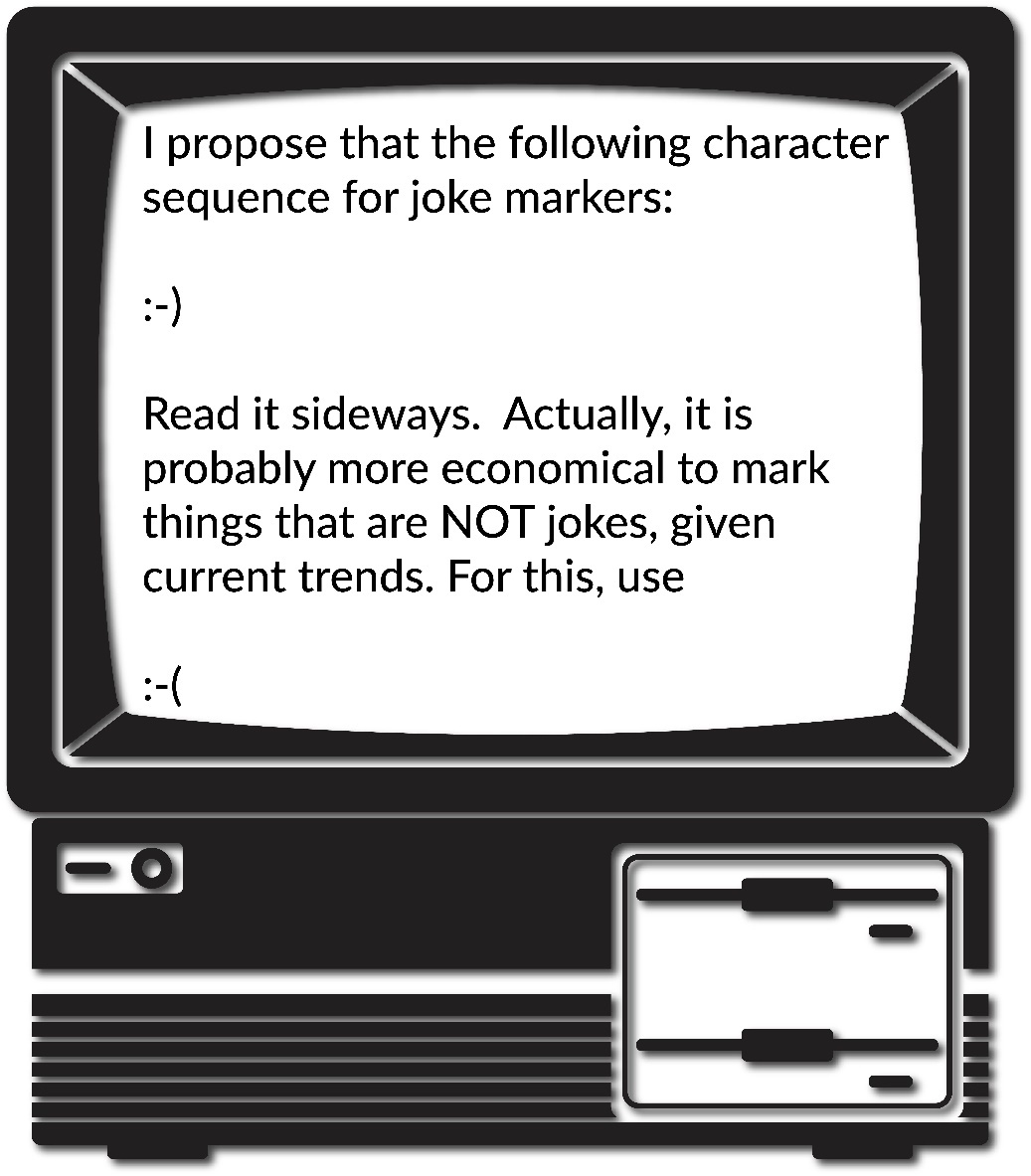

One early realization about email and message boards is that people relied solely on text to interpret a message with no form of nonverbal communication attached. On September 19, 1982, Scott Fahlman, a research professor of computer science at Carnegie Mellon, came up with an idea. You see, at Carnegie Mellon in the early 1980s (like most research universities at the time), they had their own Bulletin Board System, which discussed everything from campus politics to science fiction. As Fahlman noted, “Given the nature of the community, a good many of the posts were humorous, or at least attempted humor,” explained Fahlman. “The problem was that if someone made a sarcastic remark, a few readers would fail to get the joke and each of them would post a lengthy diatribe in response.”2 After giving some thought to the problem, he posted the following message seen in Figure 12.3.

Thus, the emoticon (emotion icon) was born. An emoticon was a series of characters and/or letters designed to help readers interpret a writer’s intended feelings and/or tone. Over the years, many different emoticons were created some useful like the smiley and sad faces, lol (laughing out loud), ROFL (rolling on the floor laughing), :-O (surprise), :-* (kiss), 😛 (sticking your tongue out), :-/ (quizzical), :-X (sealed lips), 0:-) (angel), *\0/* (cheerleader), and so many others. As we’ve discussed previously in this text, so much of how we understand each other is based on our nonverbal behaviors, so these emoticons were an attempt to bring a lost part of the human communicative experience to a text-based communicative experience.

Asynchronous Communication

For our part, these technologies are what we call asynchronous, or a mediated form of communication in which the sender and receiver are not concurrently engaged in communication. When Person A sends a message, Person B did not need to be on the computer at the same time to receive the message. There could be a delay of hours or even days before that message received and Person B responded. In this case, asynchronous messages were akin to letter writing. As the Internet grew and speed and infrastructure became more established, the development of synchronous CMC does develop, or a mediated form of communication in which the sender and receiver are concurrently engaged in communication. When Person A sends a message, Person B is receiving that message in real-time like they would in a face-to-face (FtF) interaction. In this case, synchronous messages are akin to talking to someone on the telephone.

Synchronous Communication

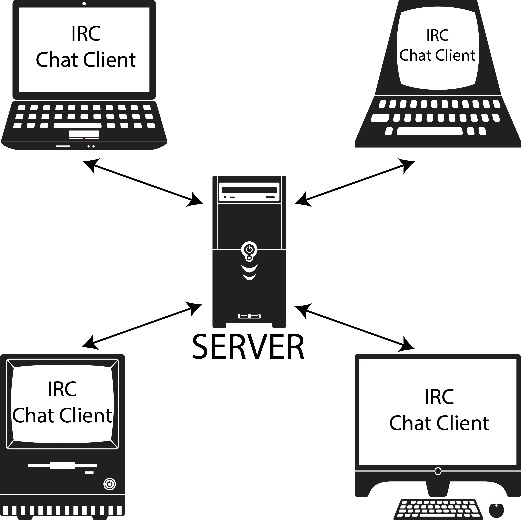

Let’s switch gears for a bit and talk about the history of synchronous communication on the Internet. The first synchronous mode of communication was the chatroom. In 1988, Jarkko “WiZ” Oikarinen wrote the first Internet Relay Chat (IRC) client and server at the University of Oulu, Finland. IRC was initially started as a program to replace an existing BBS (bulletin board system), but WiZ realized that he had something completely different. With IRC, individuals from around the world could login using an IRC Chat Client (software on their computer), which would allow them to access a server elsewhere in the world to interact with people in real-time. The invention of IRC led to the proliferation of chatrooms throughout the 1980s and 90s.

In addition to IRC, another technology developed through Germany and France cooperation on Groupe Speciale Mobile (GSM) came out in February 1985 in Oslo, Norway. The goal of the GSM was to create protocols for second-generation global cellphone networks. One of the technologies that was created was called the short messaging service (SMS). The concept was developed in 1985 by Friedhelm Hillebrand and Bernard Ghillebaert. SMS originated from radio telegraphy in radio memo pagers using standardized phone protocols and later defined as part of the Global System for Mobile Communications (GSM) series of standards in 1985. The “short” part of SMS refers to the maximum size of the messages that could be sent at the time: 160 characters (letters, numbers, or symbols in the Latin alphabet). If you haven’t figured it out yet, the system created by Hillebrand and Ghillebaert is the system most of you use every day to send text messages. Now, texting can be either asynchronous or synchronous, but we decided to talk about it here because it’s within the timeline we’re developing, and it is often used in a manner for people to communicate with one another in real-time.

The World Wide Web

Our last major invention that indeed was groundbreaking came about in 1990. Tim Berners-Lee, a scientist working for Conseil Européen pour la Recherche Nucléaire (CERN), had an idea to help capture information from the people who worked at CERN. At CERN, the typical length of someone conducting research there was only two years, so that meant a lot of new people coming and going without a way to capture what was being done. As Lee noted, “The actual observed working structure of the organisation is a multiply connected ‘Web’ whose interconnections evolve with time.”3 Unfortunately, people come and go, and those interconnections often get lost. Furthermore, “The technical details of past projects are sometimes lost forever, or only recovered after a detective investigation in an emergency. Often, the information has been recorded, it just cannot be found.”4 You see, Berners-Lee realized that so much information is learned on the job and then leaves with the people as they leave the job. Berners-Lee proposed a new system for keeping electronic information based on hypertext. After getting some initial positive feedback, Berners-Lee and Robert Cailliau wrote a management report explaining hypertext, “HyperText is a way to link and access information of various kinds as a Web of nodes in which the user can browse at will. It provides a single user interface to large classes of information (reports, notes, data-bases, computer documentation and on line help). We propose a simple scheme incorporating servers already available at CERN… A program which provides access to the hypertext world we call a browser…”5 The title of this report was “WorldWideWeb: Proposal for a HyperText Project.”

CERN was not really concerned with the Internet as its primary scope and emphasis, so they agreed to release the source code for World Wide Web (WWW) to the world in April 1993. By 1994, Berners-Lee left CERN and took a job at MIT where he created the International World Wide Web Consortium (W3C) to develop common standards for communication on the WWW. W3C still exists today, and the WWW celebrated its 30th birthday on March 10, 2019. The 5th variation of the hypertext markup language (HTML) created by the W3C is currently in circulation. You’re probably using HTML5 daily and don’t even realize it. As the W3C note, “HTML5 contains powerful capabilities for Web-based applications with more powerful interaction, video support, graphics, more styling effects, and a full set of APIs. HTML5 adapts to any device, whether desktop, mobile, tablet, or television.”6

Key Takeaways

- Starting with the invention of the Internet in 1969, computer-mediated communication has changed over the years as technology has advanced.

- Many important figures have helped create computer-mediated communication as we know it today. Some of the key players include Ray Tomlinson (inventor of email), Scott Fahlman (creator of emoticons/emojis), Jarkko “WiZ” Oikarinen (inventor of IRC), Friedhelm Hillebrand and Bernard Ghillebaert (creators of text messaging), and Tim Berners-Lee (inventor of the World Wide Web). These are just a handful of the many women and men who had a part in the development of computer-mediated communication.

Exercises

- When you look back at your own life, which computer-mediated technologies do you remember interacting with? Go back as far as you can and think about your first experiences through what you use today.

- Check out the World Wide Web Consortium’s (W3C) website (https://www.w3.org/) and see what projects they’re working on today. Why is the W3C still relevant today?

12.2 The CMC Process

Learning Objectives

- Differentiate between synchronous and asynchronous communication.

- Explain the role of nonverbal cues in computer-mediated communication.

- Describe the various rules and norms associated with computer-mediated communication and its importance to netiquette.

- Examine the human communication factors related to computer-mediated communication.

- Discuss the process and importance of forming impressions online.

As interpersonal communication scholars, our interest in CMC is less about the technologies that people are using and more about how people are using technology to interact with one another. So instead of focusing on how one goes about coding new software, interpersonal communication scholars focus on how new technologies and software help facilitate interpersonal communication. For example, Pat and Sam are playing the latest Massive Multiplayer Online Roleplaying Game (e.g., Word of Warcraft, Fortnite, etc.). As you can see in Figure 12.5, each player is playing the same video game together but from different locations. Through a technology called VoIP, Sam and Pat can play video games at the same time while talking to each other through the use of headsets.

Synchronous and Asynchronous Communication

In this section, we’re going to delve more into the areas of synchronous and asynchronous communication. In Figure 12.5, Sam and Pat are in some kind of underworld, firey landscape. Pat is playing a witch character, and Sam is playing a vampire character. The two can coordinate their movements to accomplish in-game tasks because they can freely talk to one another while playing the game in real-time. As previously discussed, this type of CMC is synchronous communication, or communication that happens in real-time. Conversely, asynchronous communication is communication is the exchange of messages with a time lag. In other words, people can communicate on their own schedules as time permits instead of in real-time. For example, Figure 12.6 shows a conversation between two college students. In this case, two college students are using SMS, commonly called texting) to interact with each other. The conversation starts at 2:25 PM. The first person initiates the conversation, but doesn’t get a response until 3:05 PM. The third turn in the interaction then doesn’t happen until 5:40 PM. In this exchange, the two people interacting can send responses at their convenience, which is one of the main reasons people often rely on asynchronous communication. Other common forms of asynchronous communication include emails, instant messaging, online discussions, etc….

Now, is it possible for people to use the same SMS technology to interact synchronously? Of course. One of our coauthors remembers two students on a trip sitting next to each other texting back-and-forth because they didn’t want their conversation to be overheard by others in the van. Their interaction was clearly mediated, and in real-time, so it would be considered synchronous communication.

Nonverbal Cues

One factor related to CMC is the issue of nonverbal communication. Historically, most of the mediums people used to interact with one another were asynchronous and text-based. As such, it was impossible to ascertain the meaning behind a string of words fully. Mary J. Culnan and M. Lynne Markus believed that the functions nonverbal behaviors meet in interpersonal interactions simply go unmet in CMC.7 As such, interpersonal communication must always be inherently impersonal when it’s conducted using computer-mediated technologies. This perspective has three underlying assumptions:

- Communication mediated by technology filters out communicative cues found in FtF interaction,

- Different media filter out or transmit different cues, and

- Substituting technology-mediated for FtF communication will result in predictable changes in intrapersonal and interpersonal variables.8

Let’s breakdown these assumptions. First, CMC interactions “filter out” communicative cues found in FtF interactions. For example, if you’re on the telephone with someone, you can’t see their eye contact, gestures, facial expressions, etc.… If you’re reading an email, you have no nonverbal information to help you interpret the message because there is none. That’s what is meant by nonverbal cues that have been filtered out. For now, we’re going to stop our discussion about nonverbal communication because we will revisit this information later in this chapter when we look at a range of theories related to CMC.

Unfortunately, even if we don’t have the nonverbals to help us interpret a message, we interpret the message using our perceptions of how the sender intended us to understand this message, which is often wrong. How many times have you seen an incorrectly read text or email start a conflict? Of course, one of the first attempts to recover some sense of nonverbal meaning was the emoticon that we discussed earlier in this chapter.

CMC Rules and Norms

As with any type of communication, some rules and norms govern how people communicate with one another. For example, Twitter has an extensive Terms of Service policy that covers a wide range of communication rules. For our purposes here, let’s examine their rules related to hate speech:

Hateful conduct: You may not promote violence against or directly attack or threaten other people on the basis of race, ethnicity, national origin, sexual orientation, gender, gender identity, religious affiliation, age, disability, or serious disease. We also do not allow accounts whose primary purpose is inciting harm towards others on the basis of these categories.

Hateful imagery and display names: You may not use hateful images or symbols in your profile image or profile header. You also may not use your username, display name, or profile bio to engage in abusive behavior, such as targeted harassment or expressing hate towards a person, group, or protected category.9

This statement is an obvious example of a rule that exists on the Twitter platform. Of course, some have argued that this rule is pretty flexible at times, given the type of hateful political speech that is often Tweeted by different political figures.

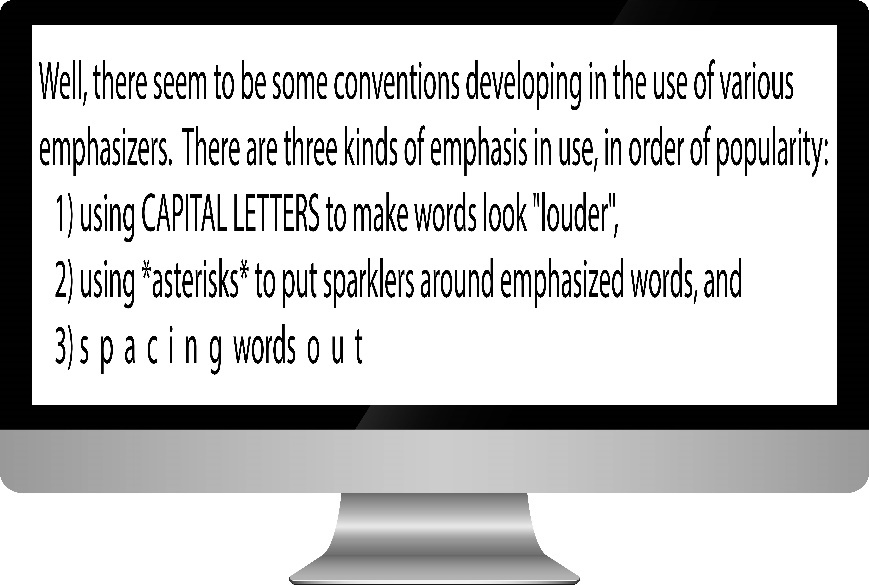

In addition to clearly spelled out rules that govern how people communicate via different technologies, there are also norms for how people communicate. A norm, in this context, is an accepted standard for how one communicates and interacts with others in the CMC environment. For example, one norm that can really frustrate people in text-based CMC environments is yelling, or TYPING IN ALL CAPITAL LETTERS. There’s actually not a consensus on when the avoidance of all capital letters as a tool for yelling first happened. We do know that newspapers in the 1880s often used all capital letters to emphasize headlines (basically have them jump off the page). At some point in the early 1980s, using all caps as a form of yelling became quite the norm, which was noted in a message post from Dave Decot in 1984 (Figure 12. 7).10

In this example, you see three different attempts to create a system for emphasizing words. The first is the use of all capital letters for making words seem “louder,” which eventually became known as yelling.

Netiquette

Over the years, numerous norms have been created to help individuals communicate in the CMC context. They’re so common that we have a term for them, netiquette. Netiquette is the set of professional and social rules and norms that are considered acceptable and polite when interacting with another person(s) through mediated technologies. Let’s breakdown this definition.

Contexts

First, we wanted to ensure that our definition emphasizes that different contexts can create different netiquette needs. Specifically, how one communicates professionally and how one communicates socially are often quite different. For example, you may find it entirely appropriate to say, “What’s up?!” at the beginning of an email to a friend, but you would not find it appropriate to start an email to your boss in this same fashion. Furthermore, it may be entirely appropriate to downplay or not worry about spelling errors or grammatical problems in a text you send to a friend, but it is completely inappropriate to have those same errors and problems in a text sent to a professional-client or coworker. One of the biggest challenges many employers have with young employees fresh out of college is that they don’t know how to differentiate between appropriate and inappropriate communicative behavior in differing contexts.

This lack of professionalism is also a problem commonly discussed by college and university faculty and staff. Think about the last email you sent to one of your professors? Was this email professional? Did you remember to sign your name? You’d be amazed at the lack of professionalism many college and university faculty and staff see in the emails sent by your peers. We mention this because the context is different from your day-to-day use of email. Here are some general guidelines for sending professional emails:

- Include a concise, direct subject line.

- Do not mark something as “urgent” unless it really is.

- Have a Proper Greeting (Dear Mr. X, Professor Y:, etc.)

- Double-check your Grammar.

- Correct any spelling mistakes.

- Include only essential information.

- Your message should be concise.

- Make your intention known clearly and directly.

- Make sure your message follows a logical organization.

- Be polite and ensure your tone is appropriate.

- Avoid all CAPS or all lowercase letters.

- Avoid “textspeak” (e.g., plz, lol, etc.)

- If you want the recipient to do something, make the desired action very clear. However, ask, don’t demand.

- Have a clear closing (using “please” and “thank you”).

- Do not send an email if you’re angry or upset.

- Edit and proofread before hitting “send.”

- Use “Reply All” selectively (very selectively).

Rules & Norms

Second, in our definition, netiquette is a combination of both rules and norms. Part of being a competent communicator in a CMC environment is knowing the rules. For example, if you know that the rules ban hate speech on Twitter, then engaging in hate speech using the Twitter platform shows a disregard for the rules and would not be considered appropriate behavior. In essence, hate speech is anti-netiquette. We also do not want to ignore the fact that norms often develop in different CMC contexts. For example, maybe you’re taking an online course and you’re required to engage in weekly discussions. One common norm in an online class is to check the previously replies to a post before posting your reply. If you don’t, then it’s like jumping into a conversation that’s already occurred and throwing your two-cents in without knowing what’s happening.

Acceptable & Polite CMC Behavior

Third, we believe that netiquette attempts to govern what is both acceptable and polite. Yelling via a text message may be acceptable to some of your friends, but is it polite given that typing in all caps is generally seen as yelling? Being polite is merely showing others respect and demonstrating socially appropriate behaviors.

Mindfulness Activity

If you’ve spent any time online recently, you may have noticed that it can definitely feel like a cesspool. There are so many trolls that are making the Internet into a negative experience. Kindness quickly gets trampled by meanness and vile attacks on someone’s character or people use a public post to spew political opinions not relevant to the topic of origin. Mitch Abblett, a clinical psychologist and mindfulness trainer, lists five specific guidelines for interacting with others online:

- Be kind and compassionately courteous with all posts and comments.

- No hate speech, bullying, derogatory or biased comments regarding self, others in the community, or others in general.

- No Promotions or Spam.

- Do not give out mental health advice.

- Respect everyone’s privacy and be thoughtful in the nature and depth of one’s sharing.12

Think about your interactions with others in the online world. Have you ever communicated with others without considering attention, intention, and attitude?

Online Interaction

Fourth, our definition involves interacting with others. Now, this interaction can be one-on-one, or this interaction can be one-to-many. The first category, one-on-one, is more in the wheelhouse for interpersonal communication. Examples could include sending a text to one person, sending an email to one person, talking to one person via Skype, etc…. One-to-many is also a possibility and will require its own sets of rules and norms. Some common examples of one-to-many CMC could include engaging in a group chat via texting, “replying all” to an email received, being interviewed by a committee via Skype, etc…. Notice that our examples for one-to-many involve the same technologies used for one-on-one communication. With one-to-many, we’re dealing with a larger number of people involved in the communicative interactions.

Range of Mediated Technologies

Lastly, netiquette can vary based on the different types of mediated technologies. For example, it may be considered entirely appropriate for you to scream, yell, and curse when your playing with your best friend on Fortnite, but it wouldn’t be appropriate using the same communicative behaviors when engaging in a video conference over Skype. Both technologies use VoIP to some extent, but the platforms and the contexts are very different, so they call for different types of communicative behaviors. Some differences will exist in netiquette based on whether you’re in an entirely text-based medium (e.g., email, texting, etc.) or one where people can see you (e.g., Skype, WebEx, etc.).

Ultimately, engaging in netiquette requires you to learn what is considered acceptable and polite behavior across a range of different technologies.

Communication Factors

Communication traits are an essential part of understanding how computer-mediated communication impacts interpersonal relationships. In this section, we’re going to examine two specific communication factors that have been researched in a variety of CMC contexts: communication apprehension and self-disclosure.

Communication Apprehension

Most of the research examining CA and CMC started at the beginning of the 21st Century. Until 1996 when America Online (AOL) provided unlimited access to the Internet for a low monthly fee, most people did not have access to the Internet because of the cost. As such, most scholars weren’t overly interested in communication traits related to CMC until the public became more actively involved interacting through the technology. One early study conducted by Scott W. Campbell and Michael R. Neer sought to see if an individual’s level of communication apprehension (CA) could predict how they felt about CMC.13 In the study, the authors predicted that an individual’s level of CA could predict whether individuals believed that CMC was an effective medium for interpersonal communication; however, the researchers did not find a significant relationship. Furthermore, the researchers found that there wasn’t a significant relationship between CA and people’s satisfaction with their CMC experiences. Here’s how the researchers attempted to make sense of these findings:

One plausible interpretation is that high apprehensives simply do not view CMC positively or negatively. Yet, they recognize that it reduces the threat posed to them in FtF settings. An equally plausible explanation is that high apprehensives do not regard CMC as an interpersonal obstacle to overcome because it is not FtF, but a substitute that fails to challenge or override their apprehension level. 14

Jason S. Wrench and Narissra M. Punyanunt-Carter furthered the inquiry into CA and CMC by exploring how people reacted to different types of CMC. Specifically, Wrench and Punyanunt-Carter were interested in examining email CA, online chatting CA, and instant messaging CA. You can see the measures that Wrench and Punyanunt-Carter created for this study in Table 12.1. It’s important to emphasize that the technologies listed here were the primary ones people utilized when this study was conducted in the mid-2000s.

Instructions: This set of questions asks you about how you feel while communicating using email. If you have never used email, please leave this section blank. Work quickly and indicate your first impression. Please indicate the degree to which each statement applies to you by marking whether you:

| Strongly Disagree | Disagree | Neutral | Agree | Strongly Agree |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

_____1. When communicating using email, I feel tense.

_____2. When communicating using email, I feel calm.

_____3. When communicating using email, I feel jittery.

_____4. When communicating using email, I feel nervous.

_____5. When communicating using email, I feel relaxed.

Instructions: This set of questions asks you about how you feel while communicating in online chat rooms, IRCs, or MUDDS. If you have never used chat rooms, IRCs, or MUDDS, please leave this section blank. Work quickly and indicate your first impression. Please indicate the degree to which each statement applies to you by marking whether you:

| Strongly Disagree | Disagree | Neutral | Agree | Strongly Agree |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

_____6. When communicating in a chat room, IRC, or MUDD, I feel tense.

_____7. When communicating in a chat room, IRC, or MUDD, I feel calm.

_____8. When communicating in a chat room, IRC, or MUDD, I feel jittery.

_____9. When communicating in a chat room, IRC, or MUDD, I feel nervous.

_____10. When communicating in a chat room, IRC, or MUDD, I feel relaxed.

Instructions: This set of questions asks you about how you feel while communicating using Internet Messaging Programs like AOL Instant Messenger, Yahoo Messenger, or MSN Messenger. If you have never used Internet Messaging Programs, please leave this section blank. Work quickly and indicate your first impression. Please indicate the degree to which each statement applies to you by marking whether you:

| Strongly Disagree | Disagree | Neutral | Agree | Strongly Agree |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

_____11. When communicating using an Internet messaging program, I feel tense.

_____12. When communicating using an Internet messaging program, I feel calm.

_____13. When communicating using an Internet messaging program, I feel jittery.

_____14. When communicating using an Internet messaging program, I feel nervous.

_____15. When communicating using an Internet messaging program, I feel relaxed.

Scoring: To compute your scores follow the instructions below:

Email Apprehension

A: Add scores for items 1, 3, and 4_____

B: Add scores for items 2 and 5_____

C: Take the total from A and add 12 to the score. Place the new number on the line._____

Final Score: Now subtract B from C. Place your final score on the line._____

Chatting Apprehension

A: Add scores for items 6, 8, 9, and 10_____

B: Add scores for items 7 and 10_____

C: Take the total from A and add 12 to the score. Place the new number on the line._____

Final Score: Now subtract B from C. Place your final score on the line._____

Instant Messaging Apprehension

A: Add scores for items 11, 13, and 14._____

B: Add scores for items 12 and 15._____

C: Take the total from A and add 12 to the score. Place the new number on the line._____

Final Score: Now subtract B from C. Place your final score on the line._____

Interpreting Your Score:

Scores on all three measures should be between 5 and 25. For email apprehension, scores under 9.5 are considered low and scores over 9.5 are considered high. For chatting apprehension, scores under 11.5 are considered low and scores over 11.5 are considered high. For instant messaging apprehension, scores under 9 are considered low and scores over 9 are considered high.

Source:

Wrench, J. S., & Punyanunt-Carter, N. M. (2007). The relationship between computer-mediated-communication competence, apprehension, self-efficacy, perceived confidence, and social presence. Southern Journal of Communication, 72, 355-378.

Table 12.1 Computer-Mediated Communication Apprehension (CMCA). Reprinted with permission of the authors here.

In addition to CMCA, the authors were also interested in an individual’s skill levels with CMC. CMC skill was listed as three distinct concepts: computer efficacy (individuals’ confidence in using a computer), Internet efficacy (individuals’ confidence in using the Internet), and CMC competence. Brian H. Spitzberg believed that CMC competence consisted of three important factors: 1) people must be motivated to interact with others competently, 2) people must possess specialized knowledge and technical know-how, and 3) people must learn the rules and norms for communicating in the CMC context.15 In the Wrench and Punyanunt-Carter study, the researchers found that CMCA was negatively related to computer efficacy, Internet efficacy, and CMC competence.

In a subsequent study by Daniel Hunt, David Atkin, and Archana Krishnan, the researchers set out to examine CMCA and Facebook interactions.16 Hunt, Atkin, and Krishan used a revised version of the Wrench and Punyanunt-Carter CMCA scales to measure Facebook CA. Hunt, Atkin, and Krishan found that CMCA decreased one’s motivation to use Facebook as a tool for interpersonal communication. These findings were similar to those found by Narissra M. Punyanunt-Carter, J. J. De La Cruz, and Jason S. Wrench, who examined CMCA on the social media app Snapchat.17 In this study, the researchers examined CMCA with regards to satisfying a combination of both functional and entertainment needs. Functional needs were defined as needs that allow an individual to accomplish something (e.g., feel less lonely, problem-solving, meet new people, decision making, etc.). Entertainment needs were defined as needs that allow an individual to keep her/him/themselves occupied (e.g., because it’s fun, because it’s convenient, communicate easily, etc.). In this study, Punyanunt-Carter, De La Cruz, and Wrench found that individuals with high levels of Snapchat CA were more likely to use Snapchat for functional purposes and less likely to use Snapchat for entertainment purposes.

In a second study conducted by Punyanunt-Carter, De La Cruz, and Wrench, the researchers set out to examine social media CA in relation to introversion, social media use, and social media addiction.18 In this study, the researchers found that social media CA was positively related to introversion, which is in line with previous research examining CA and introversion. Furthermore, introversion was negatively related to social media use, but social media CA was not related to social media use. Lastly, both social media CA and introversion were negatively related to social media addiction. Overall, this shows that individuals with social media CA are just not as likely to use social media, so they’re less likely to become addicted.

So, what does all of this tell us? From our analysis of CA and CMC, we’ve come to the understanding that CMC is a tool for communication. Although people with high levels of CA tend to function better in a CMC environment than in a FtF one, they’re still less likely to engage in CMC when compared to those people with low levels of CMCA. People with low levels of CMCA just see CMC as another platform for communication.

Online Impression Formation

In the 21st Century, so much of what we do involves interacting with people online. How we present ourselves to others through our online persona is very important (impression formation). How we communicate via social media and how professional our online persona is can be a real determining factor in getting a job.

It’s important to understand that in today’s world, anything you put online can be found by someone else. According to the 2018 CareerBuilder.com social recruiting survey, in a survey of more than 1,000 hiring managers, 70% admit to screening potential employees using social media, and 66% use search engines to look up potential employees.19 In fact, having an online persona can actually be very beneficial. Forty-seven percent of hiring managers admit to not calling a potential employee when the employee does not have an online presence. You may be wondering what potential employers are looking for when they checkout people online. The main things employers look for is information to support someone’s qualifications (58%); whether or not an individual has a professional online persona (50%); to see what others say about the potential candidate (34%); and information that could lead a hiring manager to decide not to hire someone (22%).20 According to CareerBuilder.com, here are the common reasons someone doesn’t get a job because of her/his/their online presence:

- Job candidate posted provocative or inappropriate photographs, videos or information: 40 percent

- Job candidate posted information about them drinking or using drugs: 36 percent

- Job candidate had discriminatory comments related to race, gender, religion, etc.: 31 percent

- Job candidate was linked to criminal behavior: 30 percent

- Job candidate lied about qualifications: 27 percent

- Job candidate had poor communication skills: 27 percent

- Job candidate bad-mouthed their previous company or fellow employee: 25 percent

- Job candidate’s screen name was unprofessional: 22 percent

- Job candidate shared confidential information from previous employers: 20 percent

- Job candidate lied about an absence: 16 percent

- Job candidate posted too frequently: 12 percent21

As you can see, what you put online says a lot about you as a person to many organizations, so they are checking the Internet to see what exists about you as a person. The flip of this is that what you have online can also help get you hired. In that same study from CareerBuilder.com, they found that 57% of hiring managers have found information about a candidate online that has solidified their decision to hire that person. Here is a list of what hiring managers found that made them want to hire someone:

- Job candidate’s background information supported their professional qualifications for the job: 37 percent

- Job candidate was creative: 34 percent

- Job candidate’s site conveyed a professional image: 33 percent

- Job candidate was well-rounded, showed a wide range of interests: 31 percent

- Got a good feel for the job candidate’s personality, could see a good fit within the company culture: 31 percent

- Job candidate had great communications skills: 28 percent

- Job candidate received awards and accolades: 26 percent

- Other people posted great references about the job candidate: 23 percent

- Job candidate had interacted with company’s social media accounts: 22 percent

- Job candidate posted compelling video or other content: 21 percent

- Job candidate had a large number of followers or subscribers: 18 percent 22

As you can see, having an online presence is important in the 21st Century. Some people make the mistake of having no social media presence, which can backfire on you. In today’s social media society, having no online presence can look very strange to hiring managers. You should consider your social media presence as an extension of your resume. At the very least, you should have a LinkedIn profile because it is the social networking site most commonly used by corporate recruiters. 23

Co-Present Interactions & Mediated Communication

Before going too much further into the world of CMC, we need to explain that not everything is great and perfect with the world of CMC interactions. For this discussion, we need to focus on the idea of co-present interactions, or when people are physically occupying the same space while interacting with one another. Historically, most of interpersonal communication involved co-present interactions. With the advent of a range of communication technologies, people don’t necessarily have to be co-present to interact. On the flip side, there are many people who are co-present who use their mediated devices as a way of avoiding FtF interactions with those around them. One of our professor friends recently remarked, “when I started my career, I always had to tell students to quiet down at the beginning of class. Now, they’re already quiet because they’re all looking at their cellphones ignoring those around them.”

Now we often have to encourage collocated social interactions, or how do we get people sitting next to each other to talk to one another. Thomas Olsson, Pradthana Jarusriboonchai, Paweł Woźniak, Susanna Paasovaara, Kaisa Väänänen, and Andrés Lucero argue that there are two basic problems facing people today, “(1) the use of current technology disrupting ongoing social situations, and (2) lack of social interaction in collocated situations where it would be desirable.”25 When people don’t interact with one another, they tend to become more socially isolated and lonely, which can lead to a true feeling of disengagement with those around them.

How many times have you seen people eating out together yet spending their whole time on their smartphones checking email or texting? Many people believe that this type of multitasking actually enhances productivity, but research tends to disagree with this notion. One study actually demonstrated that when people are confronted with constant distractions like phones ringing or email alerts chiming on a smartphone, people lose an average of 10 IQ points due to these distractions.26 This drop in IQ is equivalent to missing an entire night of sleep. Furthermore, those generations that have grown up with technology are more likely to engage in multitasking behavior.27 In a 2014 study conducted by Jonathan Bowman and Roger Pace, the researchers tested the impact that cell phone usage vs. FtF conversations had while performing a complex cognitive task.28 Not surprisingly, individuals who interacted via cell phones were less adept at performing the task than those engaged in FtF interactions. Furthermore, individuals involved in the FtF interactions were more satisfied with their interactions than their peers using a cellphone. As the authors of the article note, “People think they are effectively communicating their message while dual-tasking even though they are not.”29

So how can technology benefit social interactions? In the Olsson et al. study, the researchers examined several different studies that were designed to help foster collocated social interactions.30 Table 12.2 illustrates the basic findings from their study.

| Olsson, T., Jarusriboonchai, P., Woźniak, P. et al. Technologies for Enhancing Collocated Social Interaction: Review of Design Solutions and Approaches. Comput Supported Coop Work 29, 29–83 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10606-019-09345-0. CC-BY | ||

| Role of technology | Social design objectives | Design approaches |

|---|---|---|

| Enable (previous work beyond which the reviewed literature explores) | ||

| Facilitate |

|

|

| Invite |

|

|

| Encourage |

|

|

Table 12.2 Mapping the social design objectives and design approaches interpreted from the papers to abstract enhancement categories (Roles of Technology)

In Table 12.2 you are introduced to four different ways that technology can help facilitate collocated social interaction. You are also presented with the design objectives for each of these different ways to encourage collocated social interaction along with specific design approaches that creators can use to help foster collocated social interaction. Let’s look at each of these in turn.

Enabling

First, “enabling interaction refers to the role of a technological artifact making it possible or allowing for social interaction to take place.”31 The goal of enabling is really to set up situations where collocated social interaction is possible. As such, there’s less information about specific design objectives and approaches. Furthermore, most of the research in the area of helping people interact has historically focused on enabling.

Facilitating

Second, “facilitating interaction refers to making it easier to converse, collaborate or otherwise socially interact, or to support desirable feelings, equality or suitable interaction dynamics while doing so.”32 The goal of facilitating collocated social interactions is to help ease tension and encourage people to interact while minimizing possible negative experiences people may face. For example, one of the ways to achieve facilitating is to have an open space for a shared activity. For example, an online college or university may coffee shop nights or alumni events in various cities. They don’t necessarily have specific events or agendas, but the goal is to provide a space where people can meet and interact.

Inviting

Third, “inviting interaction is about the role of informing people of the available proximal social possibilities, which can motivate to spontaneously engage in new encounters.”33 In this case, the focus is on providing people the ability to invite social interaction or respond to invitations to engage in social interaction. One of the best examples of this type of use of technology to help facilitate collocated social interaction is https://www.meetup.com/. Meetup.com provides a range of different activities and groups people can join that then meet up in the real-world. For example, in the next 24 hours, there is a Swing Dance Cruise, Writer’s Group, and Meditation Workshop I could go to just in my local area.

Encouraging

Lastly, “encouraging interaction is about incentivizing or persuading people to start interacting or maintaining ongoing interaction.”34 In the case of encouraging, it’s not just about providing opportunities, but also using technology to help nudge people into collocated social interaction. For example, an application could encourage students in an online class who live near each other to get together to study or work on a course project together. You may notice that the common design approach here is introducing constraints. This means that people are required to meet up and engage in collocated social interaction to accomplish a task because neither can do it on their own. Video games have been using a version of this for years. In many social video games, a single player will not have all of the abilities, skills, weapons, etc. to accomplish a specific goal on their own. As such, they must work with other players to accomplish a task. The only difference here is that the tasks are being completed in a FtF context instead of a mediated.

Key Takeaways

- Synchronous communication, or communication that happens in real-time; whereas, asynchronous communication is communication is the exchange of messages with a time lag.

- Nonverbal behaviors are not inherent in many forms of computer-mediated communication. With text-based messages (email, texts, IRC, etc.), there are no nonverbal cues to attend to at all. In other mediated forms (e.g., Skype, Facetime, etc.), we can see the other person, but it’s still not the same as an interaction in a FtF context.

- Netiquette is the set of professional and social rules and norms that are considered acceptable and polite when interacting with another person(s) through mediated technologies.

- A number of human communication variables have been examined within the CMC context: communication apprehension, communication competence, etc.

Exercises

- Think about the asynchronous and synchronous computer-mediated communication technologies you use regularly. Are nonverbal behaviors filtered in or out? How does this impact your ability to understand the other person?

- Have you ever violated netiquette while interacting with other people? What happened? How did other people react?

- Take a few minutes to Google yourself and see what information is easily available about you on the Internet. You may need to try a couple of variations of your name and even add your hometown if your name is very common. If you find information about yourself, how could a potential employer react to that information? Do you need to clean up your Internet profile? Why?

12.3 Taking the Self Online

Learning Objectives

- Explain Erik Erikson’s conceptualization of identity.

- Describe how Erving Goffman can help us explain online identities.

- Discuss the three types of identities expressed online from Andrew F. Wood and Matthew J. Smith.

In Chapter 3, we discussed the world of intrapersonal communication. At the beginning of this chapter, we had you describe yourself by answering the question, “Who am I?” 20 different times. Look back at that list. Now, think about yourself in the CMC context. Are you the same person in a FtF interaction as you are in a CMC interaction? Maybe, but maybe not. For example, maybe you’re a very shy person in FtF interactions, and you have problems talking with complete strangers online. However, maybe you’re a very quiet person in FtF interactions, but when you’re playing World of Warcraft, you suddenly become very loud and boisterous. One of the beautiful things about CMC for many people is that they can be almost anyone or anything they want to be online. In this section, we’re going to examine some specific factors related to one’s online self: identity, personality traits, communication traits, privacy, anonymity, and trust. Many social psychologists over the years have attempted to define and conceptualize what is meant by the term “identity.”

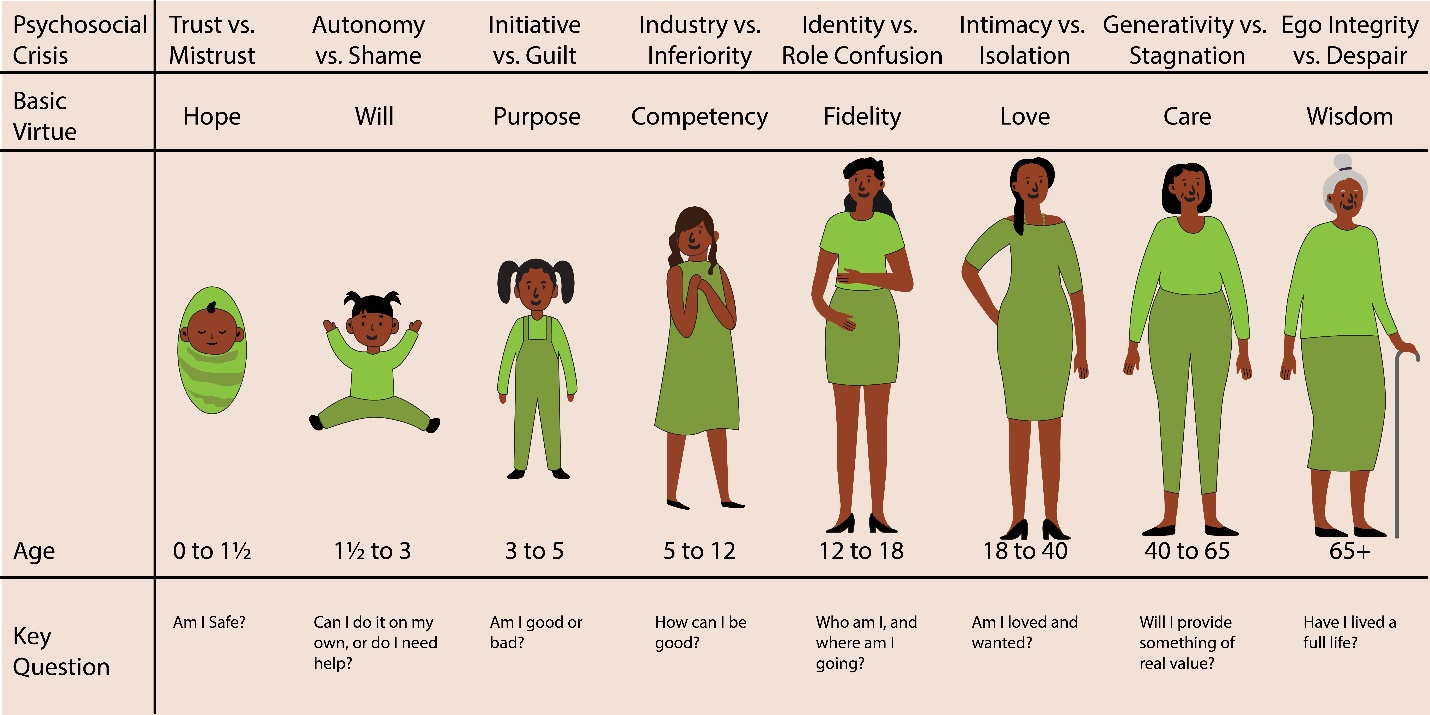

Erik Erikson

One of the more prominent contributors to this endeavor was Erik Erikson.35 Erikson believed that an individual’s identity was developed through a series of stages of psychosocial development that occur from infancy to adulthood. At each of the different stages, an individual faces various crises that will influence her/his/their identity positively or negatively. Each crisis pits the psychological needs of the individual versus the larger needs of society, which is why these crises are psychosocial in nature. You can see these stages, the crises that occur, the basic virtues associated with the crises, and the central question that is asked at each stage in Figure 12.8.

Our question then, is how does technology impact an individual’s identity development? To answer this question, we need to understand Erikson’s concept of “pseudospeciation,” or the tendency of humans to try to differentiate ourselves from other humans.36 Basically, we create in-groups (groups we belong) and out-groups (groups we do not belong). As Erikson explained, humans have a need “to feel that they are of some special kind (tribe or nation, class or caste, family, occupation, or type), whose insignia they will wear with vanity and conviction, and defend (along with the economic claims they have staked out for their kind) against the foreign, the inimical, the not-so-human kinds.”37 This need to differentiate ourselves from others is especially prominent in those individuals who are under 18 years of age.38

Millennials came of age during the influx of new technologies associated with Web 2.0, which was right during this period of identity development. Subsequent generations have grown up with technology from birth. Ever seen a baby using an iPad? It happens. Admittedly, Erikson died the same year as the first major Web browser, Netscape, came on the market. Obviously, he did not have anything to say about the influx of technology and identity formation specifically. However, he had seen the invention of other technologies and how they had impacted identity formation, specifically movies:

interspersed with close-ups of violence and sexual possession and all this without making the slightest demand on intelligence, imagination, or effort. I am pointing here to a widespread imbalance in adolescent experience because I think it explains new kinds of adolescent outbursts and points to new necessities of mastery.39

Avi Kay believes that today’s social media and other technologies are even more impactful than movies were in Erikson’s day:

An argument can certainly be made that the immediacy, pervasiveness, and intensity of the ideas and images afforded by the advent of movies pale compared to those of the Internet and social media. As such, reactions to those ideas and images via the Internet can only be expected to provoke even greater passions than those Erikson observed among the youth of his generation.40

Kay then specifically discusses how the Internet is being used as a tool to radicalize young people in Islamic countries, and the same is also true of many young people in the United States who are radicalized through the Internet into hate groups here. The Internet is a fantastic tool, but the types of information that it can expose an adolescent to during their formative years can send them on a prosocial and anti-social path. Thankfully, there is hope. As Erikson himself said, “There is no reason to insist that a technological world, as such, need weaken inner resources of adaptation, which may, in fact, be replenished by the goodwill and ingenuity of a communicating species.”41 Although many forces try to sway adolescents towards anti-social behavior and ideologies, technology isn’t inherently bad for identity formation. Technology can also be used to help forge positive identities, as well.

Your Online Identity

We just discussed how an individual’s identity could be shaped by her/his/their interaction with technology, but what about the identity we display when we’re online. In the earliest days of the Internet, it was common for people to be completely anonymous on the Internet (more on this in a minute). For our purposes, it’s important to realize that different people present themselves differently in CMC contexts. For example, someone chatting with a complete stranger on Tinder may act one way and then act completely differently when texting with her/his/their mother.

Erving Goffman and Identity

Erving Goffman, in his book The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life, was the first to note that when interacting with others, people tended to guide or control the presentation of themselves to the other person.42 As people, we can alter how we look (to a degree), how we behave, and how we communicate, and all of these will impact the perception that someone builds of us during an interaction. So, while we’re attempting to create an impression of ourselves, the other person is also attempting to create a perception of who you are as a person at the same time.

In an ideal world, how we hope we’re presenting ourselves will be how the other person interprets this self-presentation, but it doesn’t always work out that way. Goffman coined this type of interactive sensemaking the dramaturgical analysis because he saw the faces people put when interacting with others as similar to roles actors put in on a play. In this respect, Goffman used the term “front stage” to the types of behavior we exhibit when we know others are watching us (e.g., an interpersonal interaction). “Backstage” then is the behavior we engage in when we have no audience present, so we are free from the rules and norms of interaction that govern our day-to-day interactions with others. Basically, we can let our hair down and relax by taking off the character we perform on stage. At the same time, we also prepare for future interactions on stage while we’re backstage. For example, maybe a woman will practice a pick up line she plans on using in a bar after work, or a guy will rehearse what he’s going to say when he meets his boyfriend’s parents at dinner that night.

Erving Goffman died in 1982 well before the birth of the WWW and the Internet as most of us know it today, so he didn’t write about the issue of online identities. Syed Murtaza Alfarid Hussain applied Goffman’s dramaturgical approach to Facebook.43 Alfarid Hussain argues that Facebook can be seen as part of the “front stage” for interaction where we perform our identities. As such, Facebook “provides the opportunity for individuals to use props such as user profile information, photo posting/sharing/tagging, status updates, ‘Like’ and ‘Unlike’ others posts, comments or wall posts, profile image/cover page image, online befriending, group/community membership, weblinks and security and privacy settings.”44 Maybe you sat in front of your smartphone, tablet computer, laptop, or desktop computer and wanted to share a meme, but realized that many people you’re friends with on Facebook wouldn’t find the meme humorous, so you don’t share the meme. When you do this, you are negotiating your identity on stage. You are determining and influencing how others will view you through the types of posts you make, the shares you make, and even the likes you give to others’ posts.

In another study examining identity in blogging and the online 3D multiverse SecondLife, Liam Bullingham and Ana C. Vasconcelos found that most people who blog and those who participated on SecondLife (in their study) “were keen to re-create their offline self online. This was achieved by creating a blogging voice that is true to the offline one, and by publishing personal details about the offline self online, or designing the avatar to resemble the offline self in SecondLife, and in disclosing offline identity in SL.”45 In “Goffman-speak,” people online attempt to mimic their onstage performances across different mediums. Now clearly, not everyone who blogs and hangs out in SecondLife will do this, but the majority of the individuals in Bullingham and Vasconcelos’ study did. The authors noted differences between bloggers and SecondLife users. Specifically, SecondLife users have:

more obvious options to deviate from the offline self and adopt personae in terms of the appearance of the 3D avatar. In blogging, it is perhaps expected that persona adoption does not occur, unless a detachment from the offline self is obvious, such as in the case of pseudonymous blogging. Also, the nature of interaction is different, with blogging resembling more closely platform performances and the SL environment offering more opportunities for contacts and encounters.46

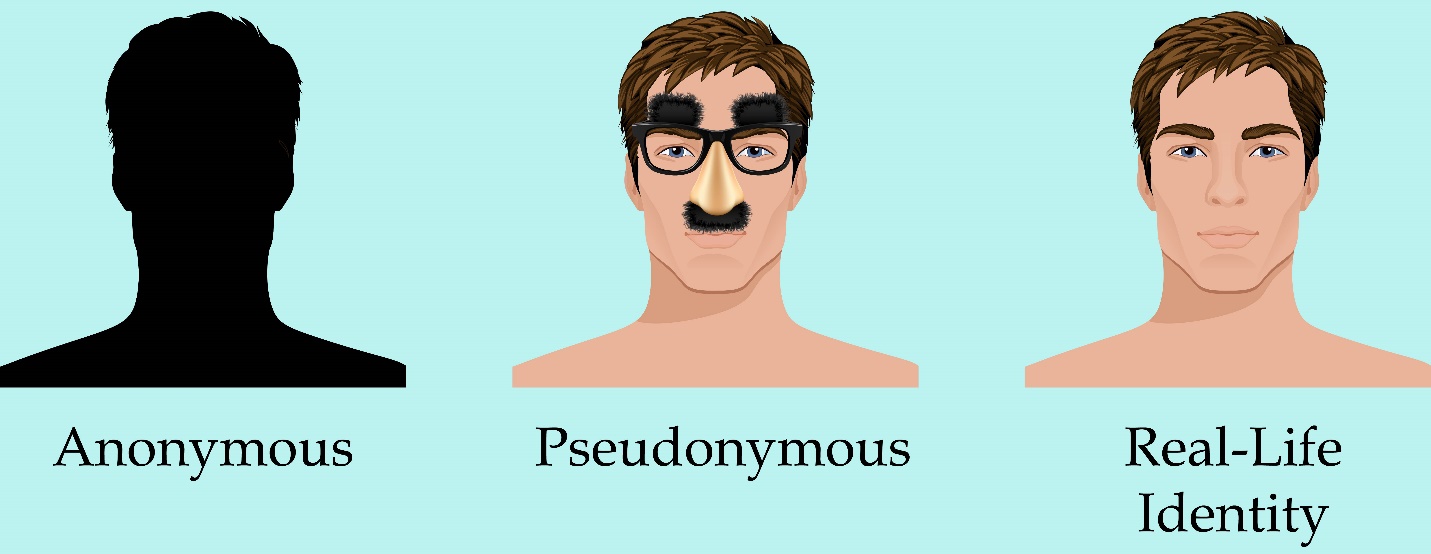

Types of Online Identities

Unlike traditional FtF interactions, online interactions can go even further blurring the identities as people act in ways impossible in FtF interaction. Andrew F. Wood and Matthew J. Smith discussed three different ways that people express their identities online: anonymity, pseudonymity, and real-life (Figure 12.9).47

Anonymous Identity

First, people in a CMC context can behave in a way that is completely anonymous. In this context, one’s actual identity is simply not known. Some people, in certain situations, prefer to take this anonymous approach when interacting with others online, and there can be legitimate reasons to do so. Individuals in challenging relationship situations, identity crises, or those connected to influential positions, might be able to find and explore help or support online through an anonymous identity. By forming anonymous relationships with others dealing with the same issues one might be able to work through some options, build some confidence, gather some resources, or feel more safe in getting mental or physical health answers.

It may be possible for some people to figure out who an anonymous person is (e.g., the NSA, the CIA, etc.), but if someone wants to maintain her or his anonymity, it’s often possible to do so. Think about how many fake Facebook, Twitter, Tinder, Grindr accounts exist. Some exist to try to persuade you to go to a website (often for illicit purposes like hacking your computer), while others may be attempting “catfishing” for the fun of it. Not all anonymity online is used for good.

Catfishing is a deceptive activity perpetrated by Internet predators where they fabricate online identities on social networking sites to lure unsuspecting victims into an emotional/romantic relationship. In the 2010 documentary Catfish, we are introduced Yaniv “Nev” Schulman, a New York-based photographer, who starts an online relationship with an 8-year-old prodigy named Abby via Facebook. Over the course of nine months, the two exchange more than 1,500 messages, and Abby’s family (mother, father, and sister) also become friends with Nev on Facebook as well. Throughout the documentary, Nev and his brother Ariel (who is also the documentarian) start noticing inconsistencies in various stories that are being told. Music that was allegedly created by Abby is found to be right off of YouTube. Ariel convinces Nev to continue the relationship knowing that there are inconsistencies and lies just to see how it will all play out. The success of Catfish spawned a television show by the same name on MTV.

From this one story, we can easily see the problems that can arise from anonymity on the Internet. Often behavior that would be deemed completely inappropriate in a FtF encounter suddenly becomes appropriate because it’s deemed as “less real” by some. One of the major problems with anonymity online has been cyberbullying. Teenagers today can post horrible things about one another online without any worry that the messages will be linked back to them directly. Unlike bullying that happened at school, teens facing cyberbullying cannot even find peace at home because the Internet follows them everywhere.

It’s also important to understand that cyberbullying isn’t just a phenomenon that happens with children. There are many statistics correlating cyberbullying to increased mental and physical health issues. Do a quick google search to see some of the latest statistics on cyberbullying in teens, pre-teens, and adults.

The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and their National Institutes of Health reported in 2022 that “Adolescents who experienced cyberbullying were more than four times as likely to report suicidal thought and attempts than those who did not.”[1] Unfortunately, far too many of them act out and succeed on those tragic thoughts.

Pseudonymous Identity

Second, the second category of interaction is pseudonymity CMC identity. Wood and Smith used the term pseudonymous because of the prefix “pseudonym,” “Pseudonym comes from the Latin words for ‘false’ and ‘name,’ and it provides an audience with the ability to attribute statements and actions to a common source [emphasis in original].”50 Whereas an anonym allows someone to be completely anonymous, a pseudonym “allows one to contribute to the fashioning of one’s own image.”51

Using pseudonyms is hardly something new. Famed mystery author Agatha Christi wrote over 66 detective novels, but still published six romance novels using the pseudonym Mary Westmacott. Bestselling science fiction author Michael Crichton (of Jurassic Park fame – among others), wrote under three different pseudonyms (John Lange, Jeffery Hudson, and Michael Douglas) when he was in medical school. Even J. K. Rowling (of Harry Potter fame) used the pseudonym Robert Galbraith to write her follow-up novel to the series. Rowling didn’t want the hype or expectation while writing her follow-up novel. Unfortunately for Rowling, the secret didn’t stay hidden very long.

There are many famous people who use pseudonyms in their social media: @TheTweetOfGod (comedy writer and Daily Show producer, David Javerbaum), @pewdiepie (online personality and producer Felix Arvid Ulf Kjellberg), @baddiewinkle (Octogenarian fashionista and online personality Helen Van Winkle), @doctor.mike (Internet celebrity family practitioner Dr. Mike Varshavski), etc…. Some of these people used parts of their real names, and others used complete pseudonyms. All of them have enormous Internet followings and have used their pseudonyms to build profitable brands. So, why do people use a pseudonym?

The veneer of the Internet allows us to determine how much of an identity we wish to front in online presentations. These images can range from a vague silhouette to a detailed snapshot. Whatever the degree of identity presented, however, it appears that control and empowerment are benefits for users of these communication technologies.52

Now, some people adopt a pseudonym because their online actions may be “out of brand” for their day-job or because they don’t want to be fully exposed online.

Real Life Identity

Lastly, some people have their real-life identities displayed online. Some people in the public eye, use some variation of their real names to enhance their brands. Some of these same people may have multiple online accounts (which may or may not be completely anonymous or could be done under a pseudonym). But for many of us, some part of our real life identity is already online. We might even, more often than not, choose this as the identity with which we approach CMC. When one does this, it’s important to remember the philosophy that what’s online, stays online, even after it may have been deleted. Assume everything you put out there can someday be seen publicly. Many mindful professionals try not to put anything on social media sites that they wouldn’t want other professionals to see and read, which is generally a good rule we all should try to remember.

Key Takeaways

- Erikson believed that an individual’s identity was developed through a series of stages of psychosocial development that occur from infancy to adulthood. At each stage, we face a different set of crises that pits the psychological needs of the individual versus the larger needs of society. Part of this development is impacted by the introduction of new technologies, which can be both good for society and problematic.

- Erving Goffman in his book The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life, used the term “front stage” to the types of behavior we exhibit when we know others are watching us (e.g., an interpersonal interaction), and he used the term “backstage” to refer to behavior we engage in when we have no audience present, so we are free from the rules and norms of interaction that govern our day-to-day interactions with others.

- Andrew F. Wood and Matthew J. Smith discussed three specific types of online identities that people can formulate: anonymity (the person behind a message is completely unknown), pseudonymity (someone uses a pseudonym, but people know who the real person behind the message is), and real-life (when our online and FtF identities are the same).

Exercises

- Of the two theoretical approaches to identity (Erikson and Goffman), which do you think is the better tool for explaining how your online identity and offline identy were formed? Why?

- When it comes to your online CMC behavior, do you have an anonymous, pseudonymous, and real-life identity? If so, how are these similar? How are they different?

12.4 Theories of Computer-Mediated Communication

Learning Objectives

- Describe uses and gratifications theory and how it helps us understand CMC behavior.

- Describe social presence theory and how it helps us understand CMC behavior.

- Describe media richness theory and how it helps us understand CMC behavior.

- Describe social information processing theory and how it helps us understand CMC behavior.

Most of the early work in computer-mediated communication from a theoretical perspective was conducted using old mediated theories created to discuss the differences between print, radio, and television and applying them to the Internet. As such, we don’t see the proliferation of theories. To help us understand the theories of computer-mediated communication, we are going to explore five theories and their implications for CMC.

Uses and Gratifications Theory

The first major theory used to explain CMC is the uses and gratifications theory. Uses and gratifications theory was originally devised back in the mid-1970s to explain why people use the types of mass media they do.53 The basic premise of the theory is that people choose various media because we get something out of that media, or it makes us happy in some way. From this perspective, people choose various media because we are have specific goals that we want to be fulfilled. Zizi Papacharissi and Alan Rubin were the first scholars to apply the uses and gratifications theory to how people use the Internet.54 Ultimately, they found five basic reasons people were using the Internet: interpersonal utility (allows people to interact with others), pass time (helps people kill time), information seeking (we look for specific information we want or need), convenience (it’s faster than FtF or even a phone call), and entertainment (people enjoy using the Internet). In this first study, the researchers found that people who used the Internet for interpersonal utility were less satisfied with life and more anxious in FtF communication interactions. Please remember that this study was conducted in 2000, so times are quite different now.

In a 2008 follow-up study, the picture of Internet socializing was pretty different, so it’s not surprising that the results were indicative of changes in public consumption.55 In this study, people found their interpersonal Internet relationships satisfying if used CMC for self-fulfillment purposes and when they intimately disclosed their personal feelings to others. In essence, if people are using the technology to make their lives better, and they are willing to self-disclose on the Internet, they are going to have more rewarding interpersonal interactions online. However, when people try to substitute FtF interpersonal interactions for CMC interactions, they do not find their CMC interactions as rewarding. On the flip side, when people supplement their FtF interpersonal interactions with CMC interactions, they are fulfilled by those interactions.

Social Presence Theory

The second major theory that has been used to help explain CMC is social presence theory. Social presence theory was originally created by John Short, Ederyn Williams, and Bruce Christie.56 Presence is a psychological state of mind and how we relate to technology. When we are truly present, we forget that we are actually using technology. Social presence then is “the degree to which we as individuals perceive another as a real person and any interaction between the two of us as a relationship.”57 Once again, our perceptions of presence are largely based on the degree to which we have the ability to interpret nonverbal cues from the people with whom we are interacting.

When it comes to CMC, various technologies are going to have varying degrees of presence. For example, reading information on a website probably is not going to make you forget that you are reading text on a screen. On the other hand, if you’re engaging in a conversation with your best friend via text messaging, you may forget about the technology and just view the interaction as a common one you have with your friend. In essence, people can vary in how they perceive presence. One of our coauthors regularly has students in a CMC course spend time in a couple of virtual worlds like SecondLife and World of Warcraft. SecondLife is a virtual world where people can create avatar and interact in a 3D simulated environment. However, it’s not a game – it’s a 3D virtual world. There is no point system and there is no winning or beating the system. Instead, it’s a place for people to socialize and interact. On the other hand, World of Warcraft (WOW) is first and foremost a game. Although there are definitely highly interactive components involved in WOW and people make life-long friends in WOW, WOW is a virtual world that has a specific end result focused on winning.

These different worlds have different purposes, but people can find both of them highly present. When students who are not familiar with these virtual worlds enter them, they often have a hard time understanding how people can spend hours upon hours interacting with others within these virtual worlds. To the students, they view this as a “strange” experience and experience no social presence at all. Conversely, to the people who “live” in these virtual worlds regularly, they experience high levels of social presence. We do know that those individuals who report higher levels of social presence tend to have more rewarding online interpersonal interactions and are more likely to perceive themselves as competent communicators within these mediated environments.58

Media Richness Theory

Our third major theory that has been applied to CMC is media richness theory. Media richness theory was first proposed by Richard L. Daft and Robert H. Lengel.59 Richness is defined as “the potential information carrying capacity of data.”60 In Lengel’s doctoral dissertation, he had proposed that media varied in richness depending on how much information is provided through the communication.61 For example, in print media, all you have is text. As such, you have no nonverbal behaviors of the author to help you interpret the words you are reading. With FtF communication, on the other hand, we have the full realm of nonverbal behaviors that we can attend to in an effort to understand the sender’s message. As such, Lengel argued that media escalates in richness in the following order: computer output, formal memos, personal memos, telephone, and FtF. You’ll notice that this perspective on media was originally designed to help individuals understand the media choices used in organizations.

So, where does this leave us with CMC? Well, from the basic ideas of media richness theory, we can ascertain that the richer the media, the less ambiguous a message is for a receiver. As such, the more rich an individual perceives a medium, the more likely they are to have successful social interactions online. From an organizational perspective, the richer the medium, the better individuals will be able to accomplish specific tasks when they are at a distance from one another. When it comes to the workplace, the more ambiguous a task is, the more people prefer highly rich media for their interactions.62

Social Information Processing Theory