44 The Phrase, Archetypes, and Unique Forms

John Peterson

Key Takeaways

This chapter introduces the phrase, the sentence, the period, the repeated phrase, compound forms, and unique phrase-level forms.

- A phrase is a relatively complete thought that exhibits trajectory toward a goal. In tonal classical music, that goal is almost always one of the traditional cadence types, but in other kinds of music, that goal may be something else.

- A sentence is a special kind of phrase that contains a presentation and a continuation.

- Sometimes phrases are combined to form larger forms. Two such combinations of phrases are:

- The period: a phrase-level form consisting of an antecedent and a consequent.

- The repeated phrase: two phrases where the second is a written-out repeat of the first.

- Sometimes two sentences are arranged in an antecedent-consequent relationship to create a compound period.

- Although the forms discussed in this chapter are all quite common, it’s equally common for a composer to write a unique phrase-level form that isn’t in dialogue with the ones discussed here.

The Phrase

A phrase is a relatively complete thought that exhibits trajectory toward a goal, arriving at a sense of closure. In tonal classical music, the goal of a phrase is almost always one of the kinds of cadences described in the Introduction to Harmony, Cadences, and Phrase Endings chapter: perfect authentic cadences (PACs), imperfect authentic cadences (IACs), and half cadences (HCs).[1]

A phrase can be any length, but phrases of 4, 8, or 16 measures are particularly common. Example 1 shows a segmentation analysis for a phrase of 4 measures (a common length), while Example 2 shows a segmentation analysis for a phrase of 13 measures (an unusual length).

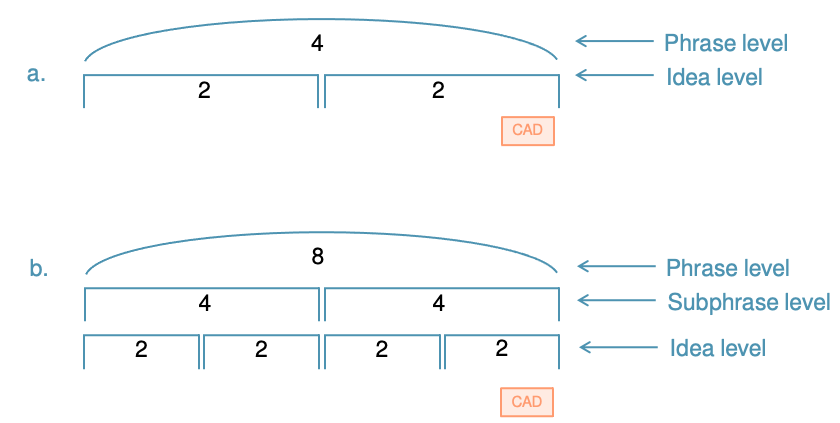

Phrases can comprise either ideas or both subphrases and ideas. The diagrams in Example 3 depict both of these scenarios.

When we diagram phrases, we follow two general principles:

- Square brackets are used for ideas and subphrases (essentially anything that doesn’t have to end with a cadence).

- Arcs are used for anything at the phrase level or above (essentially anything that must end with a cadence).[2]

Because closure is so important for phrase identification, it’s crucial to correctly identify cadences. Not every pause or V–I motion is a cadence! Example 4 discusses a passage with multiple locations someone might mistakenly label as cadences.

Example 4. A passage with multiple locations someone might mistakenly label as cadences in Haydn’s Piano Trio in F Major, Hob. XV:6, I (0:00–0:24).

Two Categories: Archetypes vs. Unique Forms

Below, we’ll explore two main ways that phrase-level forms might be organized:

- They might play with what we’ll call an archetype. These are special ways of organizing phrases, and you’ll read about two kinds: sentences and periods.

- They might not relate to an archetype at all, in which case we’ll say they’re unique forms, meaning they are not organized as sentences or periods.

Note that this doesn’t mean that archetypes are more common than unique forms. Phrase-level forms belonging to both categories appear frequently in common-practice music. Moreover, these categories might best be viewed as two ends of a spectrum (Example 5) in which a phrase-level form can be understood as “closer” to one category or the other without clearly belonging to either one.

Example 5. A spectrum of phrase-level formal categories.

Archetype 1: The Sentence (A Special Kind of Phrase)

The Basics

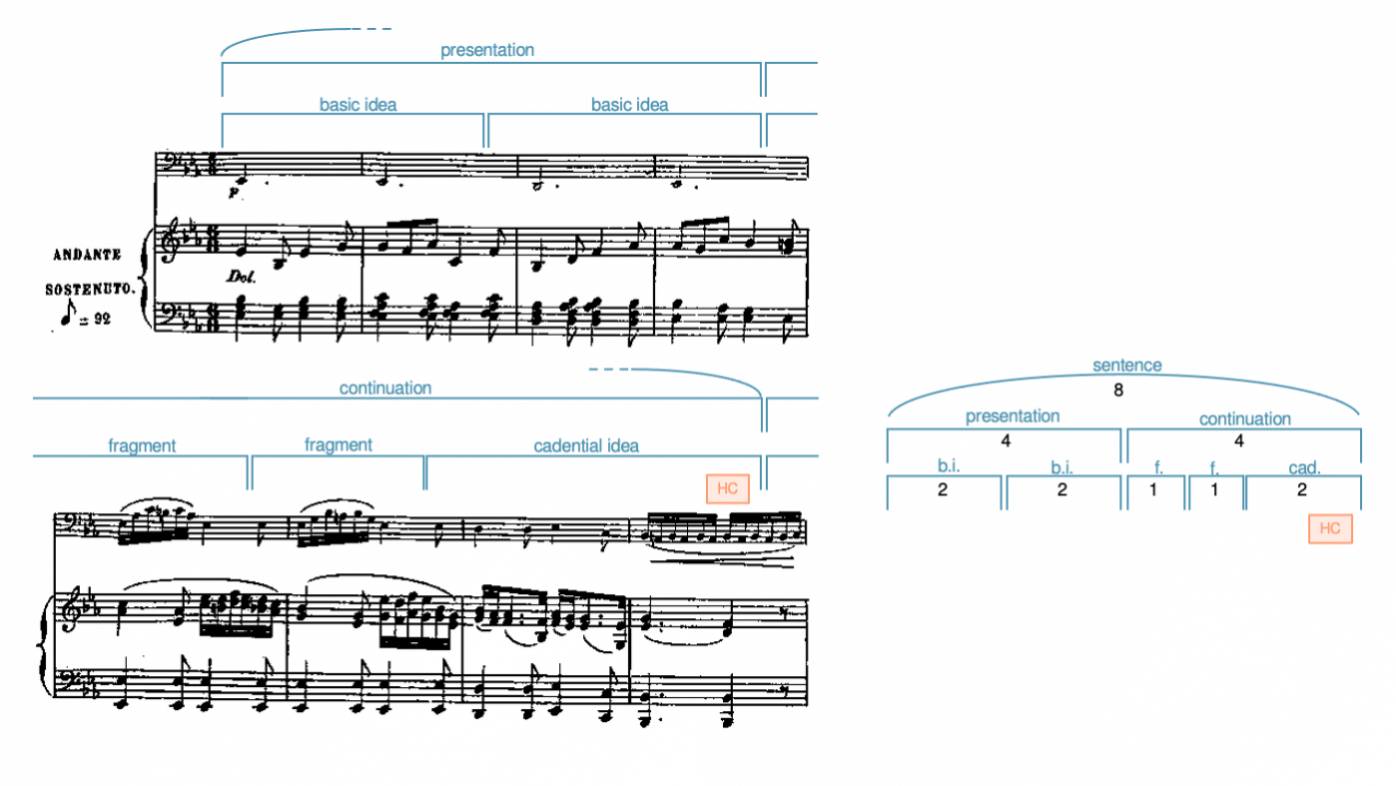

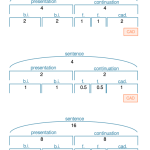

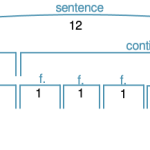

Example 6 shows one common way to construct a phrase, called a sentence. A sentence consists of two subphrases: the presentation and the continuation. The presentation is often four measures long, and it consists of a basic idea (b.i.) and its repetition. The continuation is often the same length as the presentation, creating a sense of proportional balance. It’s characterized by four traits that are discussed below.

Although it’s common for the presentation and continuation to be the same length (several common lengths are shown in Example 7), just as often, the continuation is longer than the presentation (Example 8). However, it’s not common for the continuation to be shorter than the presentation.

More Detail: The Presentation

The presentation is a subphrase comprised of a basic idea (b.i.) and its repetition (as in the first half of Example 6).

Basic ideas are often two measures long, but one-measure or four-measure basic ideas also occur with some frequency.

The repetition of the basic idea is often varied, which can sometimes make it challenging to determine whether one is dealing with repetition or with a completely different idea. One of the characteristics that usually helps to clarify is contour: if the two ideas share the same contour, often we hear the second as a varied repetition of the first. If the two ideas have different contours, then we’re more likely to hear the second section as contrasting with the first, something that will return in our discussion of the period later in this chapter.

Some common transformations of the basic idea are:

- Rhythmic or melodic embellishment

- Transposition

- Change of harmonization

- Change of interval quality or size (or both)

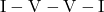

Presentations typically begin on the tonic harmony, and they may do one of several things:

- Prolong tonic via a progression such as

or

or

- Move from tonic to dominant:

- Move from tonic to a non-dominant harmony, most often a strong pre-dominant such as ii(6)

More Detail: The Continuation

The continuation is a subphrase that typically feels less stable than the presentation.

It’s characterized by four traits:

- Fragmentation (f.): making unit sizes shorter than the previously established unit sizes (e.g., if the basic ideas are each two measures, fragments may be one measure long).

- Note that fragmentation refers only to the length of the units. It does not refer to their melodic content, which may or may not be related to the basic ideas.

- Increased rhythmic activity: the use of faster durations than in previous units.

- Sequences: units are repeated and transposed.

- Increased harmonic rhythm: chord changes occur more often than before. For example, if the basic ideas are each two measures long and each is harmonized with a single chord, the continuation might contain chord changes every measure.

A continuation subphrase is easier to identify if it includes more of the traits listed above, but very often, only some of these traits are present. Perhaps the most obvious one is fragmentation, which usually signals continuation even in the absence of the other traits, but not all continuations exhibit fragmentation.

Continuations may therefore take one of two typical forms: with fragmentation (as in Example 6) and without fragmentation (as in Examples 9 and 10). In Example 9, the continuation doesn’t divide into a smaller idea level. The term unit (u.) denotes a grouping that simply expresses the traits of the next higher grouping to which it belongs; in Example 10, it indicates that the two-measure idea expresses continuation (perhaps through increased harmonic rhythm, for example).

Continuations may therefore take one of two typical forms:

- Example 6 above showed a typical continuation with fragmentation.

- Examples 8 and 9 show continuations without fragmentation.

- In Example 9, the continuation doesn’t divide into a smaller idea level.

- The term “unit” (u.) is used in Example 10 to denote a grouping that simply expresses the traits of the next higher grouping to which it belongs. Here, unit would mean that the two-measure idea expresses continuation through its increased harmonic rhythm.

Since continuations are unstable at their beginnings, it’s hard to generalize about how they might begin harmonically. In terms of their endings, however, continuations always drive toward a cadence, and in classical music, that cadence can be any of the three common kinds (perfect authentic, half, or imperfect authentic cadence).

Summary: The Archetypal Sentence and Its Variants

Sentences come in many forms: the clearest, most obvious sentences are closer to the idealized archetype, and phrases that are less clear may be highly varied while still exhibiting some traits of the sentence (we call such phrases sentential). The archetypal sentence consists of:

- 4 or 8 measures

- A presentation

- A continuation whose length balances that of the presentation

- Fragmentation in the continuation

To be clear, many sentences do not have all of these traits. At a minimum, to be sentential, a phrase needs a presentation and a continuation.

Archetype 2: The Period (A Combination of Two Phrases)

The Basics

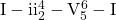

In addition to the sentence, another common phrase-level form is the period (Example 11). Unlike the sentence, which is a single phrase, the period comprises two phrases, each consisting of a basic idea (b.i.) followed by a contrasting idea (c.i.) (see below on how the treatment of these ideas differs in each phrase). The first phrase, called the antecedent, is often four measures long, and it ends with a weaker cadence, most often a half cadence (HC). The second phrase is called the consequent. It ends with a stronger cadence than the antecedent, most often a perfect authentic cadence (PAC). It may be the same length as or longer than the antecedent; it’s rare for it to be shorter.

More Detail: The Antecedent

Antecedents are sometimes characterized as “asking a question” to which the consequent “provides the answer.” Another way to think of it is that the antecedent makes an incomplete statement and the consequent completes it. Both of these descriptions stem from the fact that the antecedent always ends with a weaker cadence than the consequent.

Antecedents typically start on tonic harmony, and they most often end on a half cadence. While it’s certainly possible for the antecedent to modulate, it’s more common for the it to be entirely in the tonic key.

More Detail: The Consequent

Like the antecedent, the consequent also comprises a basic idea and a contrasting idea. Most consequents begin with a basic idea that is similar or identical to that of the antecedent, but it may also be different.[3] If the two basic ideas are different, it might be useful to label the antecedent’s basic idea as “b.i.1” and the consequent’s as “b.i.2.”

The consequent’s contrasting idea is almost always different from the antecedent’s due to the fact that it must end with a stronger cadence than the antecedent. The degree of difference varies widely: sometimes the consequent’s c.i. begins like the antecedent’s and only changes near the very end; other times, the c.i. is entirely different.

Consequents most often begin on tonic harmony and end with a PAC.

Periods may either stay in a single key or modulate (i.e., change keys). If the period modulates, the change of key usually happens during the consequent.

The Repeated Phrase (Another Way to Combine Two Phrases)

Another relatively common phrase-level form—one that sometimes gets confused with the period—is the repeated phrase, which consists of a phrase followed by a written-out repeat (Example 12).

A phrase between two repeat signs would typically not be considered a repeated phrase—this term refers to a phrase with a written-out repeat that adds additional measures to the piece. The repetition is often varied (for example, the melody may be embellished during the repeat), which explains why a composer may choose to write out the phrase a second time.

In a repeated phrase, the first phrase can end with any kind of cadence, and the second phrase must therefore end with the same one. This distinguishes a repeated phrase from a period, in which the consequent ends with a stronger cadence than the antecedent.

Compound Phrase-Level Forms (Combining Archetypes)

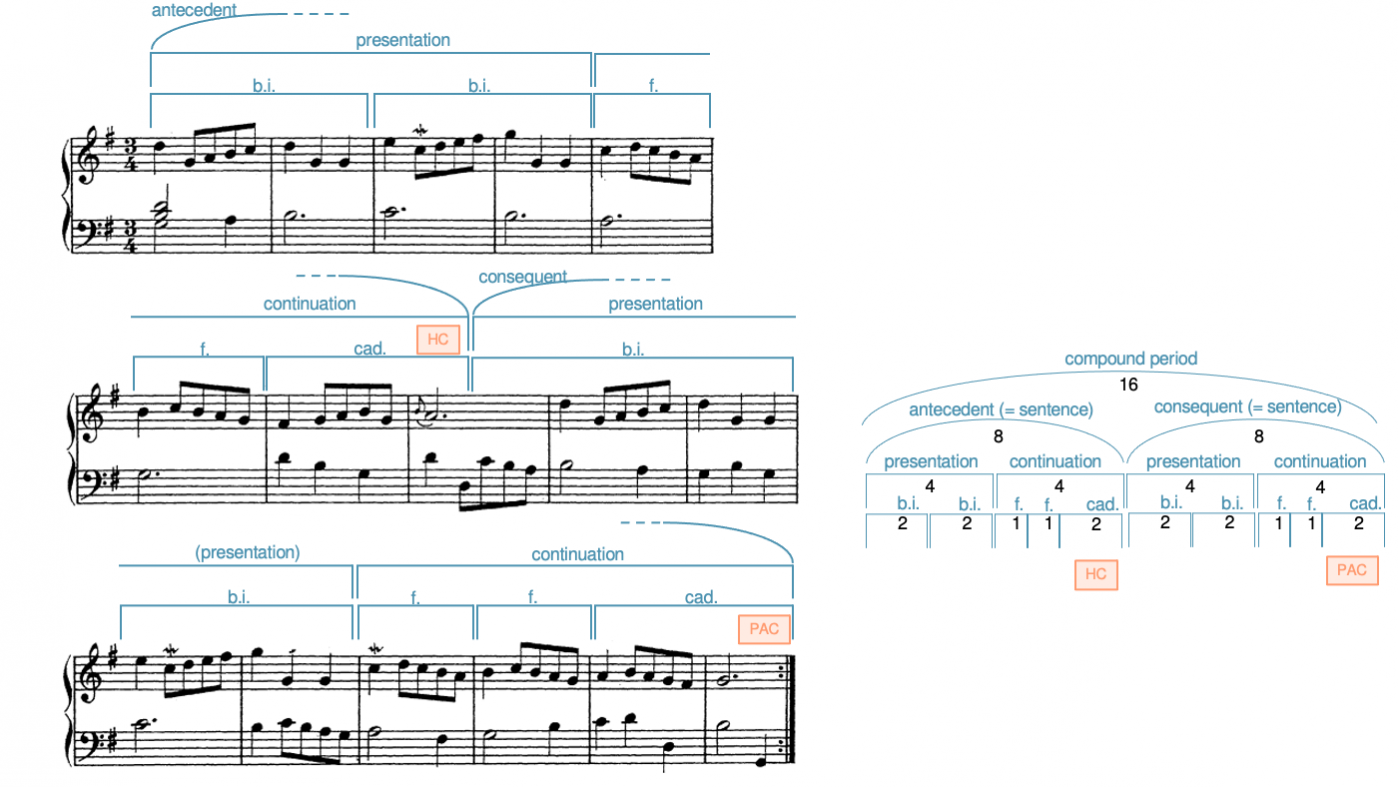

Since the sentence is a single phrase, and since the period is composed of two phrases, it’s possible for a period to be made of two sentences, as in Example 13. When one form contains another kind of form in this way, we call the result a compound form.

How is Example 13 like a period? The first phrase (the antecedent) ends with a half cadence, and the second phrase (the consequent) ends with a stronger cadence: a perfect authentic cadence. This weak-to-strong cadence pattern makes this example retain that sense of “question and answer” or “incomplete thought to completed thought” that is so characteristic of the period.

How does Example 13 use sentences? The antecedent and the consequent are each a sentence: in each phrase, the first four measures are the presentation and the last four measure are the continuation.

Unique Phrase-Level Forms

The phrase-level forms we’ve looked at in this chapter are all quite common, but just as common are phrases that are unique—that aren’t in dialogue with these archetypes in any obvious way.

When we analyze such passages, we can still perform a segmentation analysis. We can choose to apply labels flexibly, but we can also feel free to abandon labels where they don’t seem to support our interpretation. In Example 2, we showed a segmentation analysis of a phrase of unique length, and we now show how one might apply select labels to those segments in Example 14.

- Analyzing sentences (.pdf, .docx). Asks students to compare excerpts to the archetypal sentence, provide form diagrams, and optionally, provide harmonic analysis for any given excerpt. Worksheet playlist

- Analyzing archetypes and unique forms (.pdf, .docx). Asks students to identify excerpts that are archetypes (periods, sentences, compond periods) or unique forms, and to diagram those that are archetypes. Optionally, students can harmonically analyze the excerpts. Worksheet playlist

- Composing melody-only sentences (.pdf, .mscx). Students compose four-measure sentences from a given basic idea (melody only).

- Composing fully realized sentences (.pdf, .mscx). Students select from a bank of basic ideas to compose an 8-measure sentence with full texture (accompaniment and melody).

- In other kinds of music, such as post-tonal music or popular music, closure may be signaled by other kinds of devices. ↵

- See the discussion of formal hierarchy in Foundational Concepts for Phrase-Level Forms for a reminder of what is above the phrase level. ↵

- Some analysts use the term "parallel period" to describe a period in which the consequent begins the same way as the antecedent, and "contrasting period" to describe a period in which the consequent begins differently than the antecedent. Since contrasting periods are so rare, however, this book simply uses “period” to refer to a parallel period, specifying the type only in the rare instance of a contrasting period. ↵

A type of rest that lasts half the duration of a quarter rest, or the duration of two sixteenth rests.

Key Takeaways

- Nonharmonic tones can be grouped into three categories:

- Involving only stepwise motion: passing tone, neighbor tone

- Involving a leap: appoggiatura, escape tone

- Involving static notes: suspension, retardation, pedal, anticipation

Overview

One of the tools that composers use to make music more interesting is the nonharmonic tone. Nonharmonic tones are pitches that are added to a composition that are not part of the surrounding chord. The nonharmonic tone creates dissonance which in turn creates momentary musical tension - a really cool effect. In this chapter you will learn about the various different kinds of nonharmonic tones and how they work, and learn how to identify them within a musical context.

How to Spot a Nonharmonic Tone

One of the most important skills to develop when working with nonharmonic tones is learning how to identify them. Once you have located a nonharmonic tone, it becomes much easier to determine its type, as the possibilities are fairly limited. The tutorial embedded below, “Desperately Seeking Nonharmonic Tones,” gives you an opportunity to practice finding nonharmonic tones in a musical selection with simple harmony.

Types of Nonharmonic Tones

In this next section we will explore the various types of nonharmonic tones, sometimes called "embellishing tones" or "non-chord tones". These terms all mean the same thing.

Passing tones, neighbor tones: Nonharmonic tones that move by step

Example 1 showed the two kinds of embellishing tones that move by step: passing tones (PTs) and neighbor tones (NTs). Passing tones are approached by step and left by step in the same direction, either ascending or descending (Example 1). Neighbor tones are approached by step and left by step in the opposite direction, producing either an upper neighbor or a lower neighbor (Example 2).

Passing tones by openmusictheory

Example 1. Passing tones in a two-voice texture, (a) ascending and (b) descending.

Neighbor Tones by openmusictheory

Example 2. (a) Upper neighbor and (b) lower neighbor tones in a two-voice texture.

Double Neighbor Tones or Changing Tones

Double neighbor tones (DNT) (sometimes called "neighbor group" or changing tones (CT)) are made of two nonharmonic tones in a row. The first moves by step away from a chord tone, then skips to another nonharmonic tone, then moves by step to another chord tone, frequently the same chord tone.

Appoggiaturas and escape tones: Nonharmonic tones that involve a skip or leap

Appoggiaturas (APPs) and escape tones (ETs) involve either a skip or a leap. Appoggiaturas are approached by skip or leap and left by step in the opposite direction (Example 3). The appoggiatura typically occurs on a stronger part of the beat than its surrounding notes. Escape tones are approached by step and left by skip or leap in the opposite direction (Example 4). The escape tone typically occurs on a weaker part of the beat than its surrounding notes. It is more common for appoggiaturas and escape tones to be left by motion downward (Examples 3a and 4a) than upward (3b and 4b).

Appoggiatura by openmusictheory

Example 3. Appoggiaturas in a two-voice texture.

Escape Tones by openmusictheory

Example 4. Escape tones in a two-voice texture.

Examples 5 and 6 show the two kinds of embellishing tones that involve a leap: appoggiaturas and escape tones.

Joseph Boulogne, String Quartet No. 4, I, mm. 5-9 by openmusictheory

Example 5. An appoggiatura in Joseph Boulogne, String Quartet no. 4, I, mm. 5–9 (0:09-0:19).

ETs in Casson The Cuckoo by openmusictheory

Example 6. An escape tone in Margaret Casson, "The Cuckoo."

Suspensions, retardations, anticipations, and pedal tones: Nonharmonic tones involving static notes

There are four kinds of embellishing tones that involve static notes (i.e., notes that don't move): suspensions (SUS), retardations (RET), pedal tones (PED) and anticipations (ANT)

Suspensions and Retardations

Suspensions are approached by a static note and left by step down, while retardations are approached by a static note and left by step up. They follow a similar pattern:

Preparation-->Suspension (or retardation)-->Resolution

Suspensions are indicated in Roman numeral analysis not only by their abbreviations, but by the simplified intervals of the suspension and the resolution above the bass note. Retardations do not need to be labeled with the intervals above the bass note.

- 9-8. 7-6 and 4-3 suspensions are above the bass voice.

- 2-3 suspensions are in the bass voice.

- Both suspensions and retardations are always on a stronger part of the beat than the surrounding notes.

Why are all suspensions in the bass voice called 2-3 suspensions?

There is a pattern to the numbers used when the suspension is in an upper voice – the second number is always one less than the first number – 9-8, 7-6, 4-3. This is because the intervallic relationship between the upper notes and the bass voice gets smaller as the suspension resolves down by step (and closer to the bass). However, when the suspension is in the bass, the suspended note must still move down, making the resolution note farther away from all of the upper voices. This means the suspended note is closer to the upper notes, and the resolution is farther away, meaning that the intervallic relationship gets bigger. We use the numbers 2-3 because there will always be a 2-3 relationship between the suspension and resolution in the bass and one of the upper voices.

The fourth suspension in Example 7 demonstrates a 2-3 suspension. In this case the 2-3 relationship is between the bass and the "A" in the soprano voice.

Example 7 below illustrates how the melodic pattern of Preparation-->Suspension-->Resolution works, and the intervallic relationships of the various suspensions and resolutions to the bass voice.

Example 7. 9-8, 7-6, 4-3 and 2-3 suspensions.

Example 8 provides a few examples of retardations.

Example 8. Retardations by empauly

Pedal Tones

Pedal tones are often found in the bass. They consist of a series of static notes below chord changes that do not include the bass. We typically label them using the scale degree number of the pedal note, as in Example 9.

Example 9: Josephine Lang, Dem Konigs-Sohn, mm. 16-18 by openmusictheory

Anticipations

Like the suspension, retardation, and pedal tone, anticipations also involve static notes. But anticipations are a two-note (rather than three-note) gesture, in which a chord tone is heard early as a non-chord tone (Example 10). In other words, it “anticipates” its upcoming membership in a chord.

Embellishing_Tones_ by openmusictheory

Example 10. An anticipation in Josephine Lang's "Erinnerung," mm. 29–30 (1:54–1:59).

Quick Review

This tutorial by MusicTheory.Net provides a quick review/overview of nonharmonic tones. You may wish to review it now, or reference it later. If the audio does not play, please switch to a different browser.

Exercise provided by musictheory.net

Summary

The table in Example 11 provides a summary of the embellishing tones covered in this chapter.

| Embellishing Tone | Approached by | Left by | Direction | Additional Detail | Example |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Passing Tone (PT) | Step | Step | Same | May ascend or descend |  |

| Neighbor Tone (NT) | Step | Step | Opposite | Both upper and lower exist |  |

| Double Neighbor or Changing Tone (CT) | Step then Skip | Step | Varies | Chord tone to nonchord tone, to nonchord tone to chord tone |  |

| Appoggiatura (APP) | Leap | Step | Opposite | Appoggiatura is usually on a strong part of the beat |  |

| Escape Tone (ET) | Step | Leap | Opposite | Escape tone is usually on a weaker part of the beat |  |

| Suspension (SUS) | Static note | Step | Down | Suspension is always on a stronger part of the beat |  |

| Retardation (RET) | Static note | Step | Up | Retardation is always on a stronger part of the beat |  |

| Pedal Tone (PED) | Static note | Static note | N/A | Stays on the same pitch |  |

| Anticipation (ANT) | N/A | Static note | N/A | The anticipation is usually on a weaker part of the beat |  |

Example 11. Summary of embellishing tones.

- Embellishing tones (.pdf, .mscz). Asks students to write embellishing tones in a two-voice texture and label embellishing tones in an excerpt. Worksheet recording

References

This chapter is an adaptation of "Embellishing Tones" by John Peterson in Open Music Theory, vs. 2. Adaptations include:

- Adding a section on double neighbor tones.

- Adding the H5P activity "Desperately Seeking Nonharmonic Tones"

- Adding additional information on suspensions and retardations, including the section "Why are all the suspensions in the bass voice called 2-3 suspensions?"

- Amending the table summary of nonharmonic tones at the end of this chapter to include images of nonharmonic tones, which come from Victoria Malawey's chapter "Non-Chord Tones" from Multimodal Musicianship.

- Embedding the Nonharmonic Tones lesson from MusicTheory.net.

Resources

In addition to the sources cited above, the following resources were consulted in the adaptation of this chapter:

Benward, Bruce and Saker, Marilyn. (2021). Cadences and Nonharmonic Tones. Music in Theory and Practice, vol. 1.

Hutchinson, Robert. (2025). Non-Chord Tones. Music for the 21st Century Classroom.

Mount, A. (n.d.) Nonharmonic Tones. Fundamentals, Function and Form. University of Nebraska. Pressbooks.

Musictheory.net [https://www.musictheory.net]

Interactive Tutorial

All materials used in this chapter are licensed with the Creative Commons CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 International license.

Key Takeaways

- Nonharmonic tones can be grouped into three categories (summarized in Example 13):

- Involving only stepwise motion: passing tone, neighbor tone

- Involving a leap: appoggiatura, escape tone

- Involving static notes: suspension, retardation, pedal, anticipation

Overview

One of the tools that composers use to make music more interesting is the nonharmonic tone. A nonharmonic tone is a pitch that is added to a composition that is not part of the surrounding chord. The nonharmonic tone creates dissonance which in turn creates momentary musical tension - a really cool effect. In this chapter you will learn about the various different kinds of nonharmonic tones and how they work, and begin to learn how to find them within their musical context.

How to Spot a Nonharmonic Tone

One of the most challenging aspects of learning about nonharmonic tones is learning how to spot them. Once you have spotted the nonharmonic tone, it becomes much simpler to discern what type of nonharmonic tone it is, as the options are fairly limited. The tutorial embedded below, "Desperately Seeking Nonharmonic Tones" gives you a chance to practice finding nonharmonic tones in a musical selection with simple harmony.

Types of Nonharmonic Tones

In this next section we will explore the various types of nonharmonic tones, sometimes called "embellishing tones" or "non-chord tones". These terms all mean the same thing.

Passing tones, neighbor tones: Nonharmonic tones that move by step

Example 1 showed the two kinds of embellishing tones that move by step: passing tones (PTs) and neighbor tones (NTs). Passing tones are approached by step and left by step in the same direction, either ascending or descending (Example 3). Neighbor tones are approached by step and left by step in the opposite direction, producing either an upper neighbor or a lower neighbor (Example 4).

Passing tones by openmusictheory

Example 3. Passing tones in a two-voice texture, (a) ascending and (b) descending.

Neighbor Tones by openmusictheory

Example 4. (a) Upper neighbor and (b) lower neighbor tones in a two-voice texture.

Appoggiaturas and escape tones: Nonharmonic tones that involve a leap

The distinguishing characteristic of appoggiaturas and escape tones is their use of a skip or a leap. Appoggiaturas are approached by skip or leap and left by step in the opposite direction (Example 5). The appoggiatura typically occurs on a stronger part of the beat than its surrounding notes. Escape tones are approached by step and left by skip or leap in the opposite direction (Example 6). The escape tone typically occurs on a weaker part of the beat than its surrounding notes. It is more common for appoggiaturas and escape tones to be left by motion downward (Examples 5a and 6a) than upward (5b and 6b).

Appoggiatura by openmusictheory

Example 7. Appoggiaturas in a two-voice texture.

Escape Tones by openmusictheory

Example 8. Escape tones in a two-voice texture.

Examples 7 and 8 show the two kinds of embellishing tones that involve a leap: appoggiaturas (APPs) and escape tones (ETs).

Joseph Boulogne, String Quartet No. 4, I, mm. 5-9 by openmusictheory

Example 7. An appoggiatura in Joseph Boulogne, String Quartet no. 4, I, mm. 5–9 (0:09-0:19).

ETs in Casson The Cuckoo by openmusictheory

Example 8. An escape tone in Margaret Casson, "The Cuckoo."

Suspensions, anticipations, and pedal tones: Embellishing tones involving static notes

Examples 9–11 show three of the four kinds of embellishing tones that involve static notes (i.e., notes that don't move): suspensions (SUS), retardations (RET), and pedal tones (PED). A fourth kind of embellishing tone, the anticipation, deserves special comment below.

Suspensions are approached by a static note and left by step down, while retardations are approached by a static note and left by step up (Examples 9 and 10). Both suspensions and retardations are always on a stronger part of the beat than the surrounding notes. (Suspensions are discussed in greater detail in the chapter on fourth species counterpoint.)

Pedal tones are often found in the bass. They consist of a series of static notes below chord changes that do not include the bass. We typically label them using the scale degree number of the pedal note, as in Example 11.

Example 9. Suspensions and a retardation in Joseph Boulogne's String Quartet no. 4, I, mm. 47–49 (1:30–1:36).

Example 10. (a) Suspension and (b) retardation in a two-voice texture.

Example 11. Pedal tone in Josephine Lang's "Dem Königs-Sohn," mm. 16–18.

Like the suspension, retardation, and pedal tone, anticipations also involve static notes. But anticipations are a two-note (rather than three-note) gesture, in which a chord tone is heard early as a non-chord tone (Example 12). In other words, it “anticipates” its upcoming membership in a chord.

Example 12. An anticipation in Josephine Lang's "Erinnerung," mm. 29–30 (1:54–1:59).

Summary

The table in Example 13 provides a summary of the embellishing tones covered in this chapter.

[table “41” not found /]

Example 13. Summary of embellishing tones.

- Embellishing tones (.pdf, .mscz). Asks students to write embellishing tones in a two-voice texture and label embellishing tones in an excerpt. Worksheet recording

Key Takeaways

- Nonharmonic tones can be grouped into three categories (summarized in Example 13):

- Involving only stepwise motion: passing tone, neighbor tone

- Involving a leap: appoggiatura, escape tone

- Involving static notes: suspension, retardation, pedal, anticipation

Overview

One of the tools that composers use to make music more interesting is the nonharmonic tone. [pb_glossary id="1347"]Nonharmonic tones[/pb_glossary] are pitches that are added to a composition that are not part of the surrounding chord. The nonharmonic tone creates dissonance which in turn creates momentary musical tension - a really cool effect. In this chapter you will learn about the various different kinds of nonharmonic tones and how they work, and begin to learn how to find them within their musical context.

How to Spot a Nonharmonic Tone

One of the most challenging aspects of learning about nonharmonic tones is learning how to spot them. Once you have spotted the nonharmonic tone, it becomes much simpler to discern what type of nonharmonic tone it is, as the options are fairly limited. The tutorial embedded below, "Desperately Seeking Nonharmonic Tones" gives you a chance to practice finding nonharmonic tones in a musical selection with simple harmony.

Types of Nonharmonic Tones

In this next section we will explore the various types of nonharmonic tones, sometimes called "embellishing tones" or "non-chord tones". These terms all mean the same thing.

Passing tones, neighbor tones: Nonharmonic tones that move by step

Example 1 showed the two kinds of embellishing tones that move by step: passing tones (PTs) and neighbor tones (NTs). Passing tones are approached by step and left by step in the same direction, either ascending or descending (Example 3). Neighbor tones are approached by step and left by step in the opposite direction, producing either an upper neighbor or a lower neighbor (Example 4).

Passing tones by openmusictheory

Example 3. Passing tones in a two-voice texture, (a) ascending and (b) descending.

Neighbor Tones by openmusictheory

Example 4. (a) Upper neighbor and (b) lower neighbor tones in a two-voice texture.

Appoggiaturas and escape tones: Nonharmonic tones that involve a leap

The distinguishing characteristic of appoggiaturas and escape tones is their use of a skip or a leap. Appoggiaturas are approached by skip or leap and left by step in the opposite direction (Example 5). The appoggiatura typically occurs on a stronger part of the beat than its surrounding notes. Escape tones are approached by step and left by skip or leap in the opposite direction (Example 6). The escape tone typically occurs on a weaker part of the beat than its surrounding notes. It is more common for appoggiaturas and escape tones to be left by motion downward (Examples 5a and 6a) than upward (5b and 6b).

Appoggiatura by openmusictheory

Example 7. Appoggiaturas in a two-voice texture.

Escape Tones by openmusictheory

Example 8. Escape tones in a two-voice texture.

Examples 7 and 8 show the two kinds of embellishing tones that involve a leap: appoggiaturas (APPs) and escape tones (ETs).

Joseph Boulogne, String Quartet No. 4, I, mm. 5-9 by openmusictheory

Example 7. An appoggiatura in Joseph Boulogne, String Quartet no. 4, I, mm. 5–9 (0:09-0:19).

ETs in Casson The Cuckoo by openmusictheory

Example 8. An escape tone in Margaret Casson, "The Cuckoo."

Suspensions, anticipations, and pedal tones: Embellishing tones involving static notes

Examples 9–11 show three of the four kinds of embellishing tones that involve static notes (i.e., notes that don't move): suspensions (SUS), retardations (RET), and pedal tones (PED). A fourth kind of embellishing tone, the anticipation, deserves special comment below.

Suspensions are approached by a static note and left by step down, while retardations are approached by a static note and left by step up (Examples 9 and 10). Both suspensions and retardations are always on a stronger part of the beat than the surrounding notes. (Suspensions are discussed in greater detail in the chapter on fourth species counterpoint.)

Pedal tones are often found in the bass. They consist of a series of static notes below chord changes that do not include the bass. We typically label them using the scale degree number of the pedal note, as in Example 11.

Example 9. Suspensions and a retardation in Joseph Boulogne's String Quartet no. 4, I, mm. 47–49 (1:30–1:36).

Example 10. (a) Suspension and (b) retardation in a two-voice texture.

Example 11. Pedal tone in Josephine Lang's "Dem Königs-Sohn," mm. 16–18.

Like the suspension, retardation, and pedal tone, anticipations also involve static notes. But anticipations are a two-note (rather than three-note) gesture, in which a chord tone is heard early as a non-chord tone (Example 12). In other words, it “anticipates” its upcoming membership in a chord.

Example 12. An anticipation in Josephine Lang's "Erinnerung," mm. 29–30 (1:54–1:59).

Summary

The table in Example 13 provides a summary of the embellishing tones covered in this chapter.

[table “41” not found /]

Example 13. Summary of embellishing tones.

- Embellishing tones (.pdf, .mscz). Asks students to write embellishing tones in a two-voice texture and label embellishing tones in an excerpt. Worksheet recording

Related to European or American culture.

A physical and/or social setting.

Auditory; related to hearing.

A basic multi-phrase unit. In pop music, a strophe is a focal module within strophic-form and AABA-form songs.

A musical sound that has both a pitch and a rhythmic component; the symbol may include a stem, beam, and/or flag.

Key Takeaways

- Species counterpoint is a step-by-step method for learning to write melodies and to combine them.

- While the "rules" involved are somewhat linked to music in the 16th century, the idea really is to train basic skills, independent of a specific repertoire or style.

- This chapter recaps some key concepts we met in the Fundamentals section and introduces some basic "rules" that will be relevant for each of the following chapters, including some terms for:

- Consonance and dissonance:

- Perfect consonances: perfect unisons, fifths, and octaves

- Imperfect consonances: major and minor thirds and sixths

- Dissonances: all seconds, sevenths, and diminished and augmented intervals

- Types of two-part motion:

- Contrary: the two parts move in opposite directions (one up, the other down

- Similar: the two parts move in the same direction (both up or both down)

- Parallel: the two parts move in the same direction (both up or both down) by the same distance, such that the starting and ending intervals are of the same type (e.g., parallel thirds)

- Oblique: one part moves, the other stays on the same pitch

- Consonance and dissonance:

We begin with a specific method called species counterpoint. The term "species" is probably most familiar as a way of categorizing animals, but it is also used in a wider sense to refer to any system of grouping similar elements. Here, the species are types of exercises that are done in a particular order, introducing one or two new musical “problems” at each stage. (So no, we won't have any elephants or monkeys singing polyphony, sorry!)

While there are many variants on this approach, the chapters here are closely based on Johann Joseph Fux's Gradus ad Parnassum (Steps to Parnassus, 1725). Many composers from the 18th to the 21st centuries have used this method, or some variation on it. In the first part of Gradus ad Parnassum, Fux works through five species for combining two voices, which will be the focus of our next five chapters. The “Gradus ad Parnassum” Exercises chapter provides all of the exercises from Gradus ad Parnassum in an editable format so you can try this yourself.

Before getting into the five species, we begin in this chapter by introducing principles that apply to writing lines in any species. These principles build on concepts from the Fundamentals section, such as intervals and scale degrees.

Consonance and dissonance

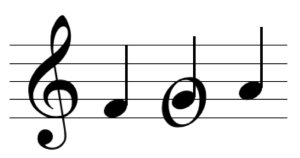

Consonance and dissonance was introduced in a previous chapter, but in counterpoint, we further distinguish between:

- Perfect consonances (perfect unisons, fifths, and octaves)

- Imperfect consonances (major and minor thirds and sixths)

- Dissonances (all seconds, sevenths, and diminished and augmented intervals)

These categories are summarized in Example 1 below.

The elusive perfect fourth

As in many theories of tonal music, the perfect fourth has a special status in species counterpoint that depends on where it appears in the texture. Basically, the interval of a perfect fourth is dissonant when it involves the lowest voice in the texture, but it is consonant when it occurs between two upper voices.

As this survey of species counterpoint will only cover two-voice textures, all fourths will involve the lowest part and therefore be classed as dissonant. Later chapters in this section will address the resolution of this dissonance, and the Strengthening Endings with Cadential [latex]^6_4[/latex] and [latex]^6_4[/latex] Chords as Forms of Prolongation chapters in the Diatonic Harmony section discuss this topic further.

Types of motion

Species counterpoint also concerns the motion between melodic lines (demonstrated in Example 2):

- Contrary: the two parts move in opposite directions (one up, the other down)

- Similar: the two parts move in the same direction (both up or both down)

- Parallel: the two parts move in the same direction (both up or both down) by the same distance, such that the starting and ending intervals are of the same type (e.g., parallel thirds)

- Oblique: one part moves, the other stays on the same pitch

Example 2. Examples of different types of motion.

Composing a Cantus Firmus

Exercises in strict voice leading, or species counterpoint, begin with a single well-formed musical line called the cantus firmus ("fixed voice" or "fixed melody"; plural "cantus firmi"). Cantus firmus composition gives us the opportunity to engage the following fundamental musical traits:

- smoothness

- independence and integrity of melodic lines

- variety

- motion (toward a goal)

Example 3 contains all the cantus firmi that Fux uses throughout Gradus at Parnassum: one for each mode, presented here in the upper and lower of two parts. Apart from using this to review the type of cantus firmi Fux composed, you can use this to practice any of the species, on any of the modes, and in both the upper and lower parts.

Example 3. Cantus firmi from Gradus ad Parnassum.

Notice how in each case, the general musical characteristics of smoothness, melodic integrity, variety, and motion toward a goal are worked out in specific characteristics. The following characteristics are typical of all well-formed cantus firmi:

- length of about 8–16 notes

- arhythmic (all whole notes; no long or short notes)

- begin and end on do [latex](\hat1)[/latex]

- approach final tonic by step: usually re–do [latex](\hat2-\hat1)[/latex], sometimes ti–do [latex](\hat7-\hat1)[/latex]

- all note-to-note progressions are melodic consonances

- range (interval between lowest and highest notes) of no more than a tenth, usually less than an octave

- a single climax (high point) that usually appears only once in the melody

- clear logical connection and smooth shape from beginning to climax to ending

- mostly stepwise motion, but with some leaps (mostly small leaps)

- no repetition of “motives” or “licks”

- any large leaps (fourth or larger) are followed by step in opposite direction

- no more than two leaps in a row and no consecutive leaps in the same direction (except in the F-mode cantus firmus, where the back-to-back descending leaps outline a consonant triad)

- the leading tone progresses to the tonic

- leading notes in all cases, including in "minor"-type modes for which that seventh degree needs to be raised

Melodic tendencies

Some of the characteristics listed above are specific to strict species counterpoint; however, taken together, they express some general tendencies of melodies found in a variety of styles.

David Huron (2006) identifies five general properties of melodies in Western music that connect to the basic principles of perception and cognition listed above, but play out in slightly different ways in specific musical styles. They are:

- Pitch proximity: The tendency for melodies to progress by steps more than leaps and by small leaps more than large leaps. An expression of smoothness and melodic integrity.

- Step declination: The tendency for melodies to move by descending step more than ascending. Possibly an expression of goal-oriented motion, as we tend to perceive a move down as a decrease in energy (movement toward a state of rest).

- Step inertia: The tendency for melodies to change direction less frequently than they continue in the same direction. (That is, the majority of melodic progressions are in the same direction as the previous one.) An expression of smoothness and, at times, goal-oriented motion.

- Melodic regression: The tendency for melodic notes in extreme registers to progress back toward the middle. An expression of motion toward a position of rest (with non-extreme notes representing “rest”). Also an expression simply of the statistical distribution of notes in a melody: the higher a note is, the more notes there are below it for a composer to choose from, and the fewer notes there are above it.

- Melodic arch: The tendency for melodies to ascend in the first half of a phrase, reach a climax, and descend in the second half. An expression of goal orientation and the rest–motion–rest pattern. Also a combination of the above rules in the context of a musical phrase.

Rules for melodic and harmonic writing

In species counterpoint, we both write and combine such melodic lines. The following set of rules invoked in all the species begins with the melodic matters discussed already, then presents some harmonic considerations that we will focus on in the following chapters.

Melodic writing (horizontal intervals)

- Approach the final octave/unison of each exercise by step (this creates the clausula vera).

- Limit the number of:

- consecutive, repeated notes: the same pitch more than once in a row

- non-consecutive repeated notes: the same pitch more than once across the whole exercise

- consecutive leaps: multiple intervals of a third or greater in a row (separate them with stepwise motion)

- non-consecutive leaps: the total number of leaps within a short span, even if they're not successive

- consecutive repeated generic intervals: the same interval size (e.g., second) even if not the same specific interval (minor second)

- Control the melodic climax (highest note):

- Aim for exactly one unique climax in each melodic part

- Avoid ending on that climax

- Preferably leap to that climax

- Avoid the two parts reaching their respective climax pitches at the same time

- Avoid melodic leaps of:

- an augmented interval

- a diminished interval

- any seventh

- any sixth, except perhaps the ascending minor sixth

- any interval larger than an octave

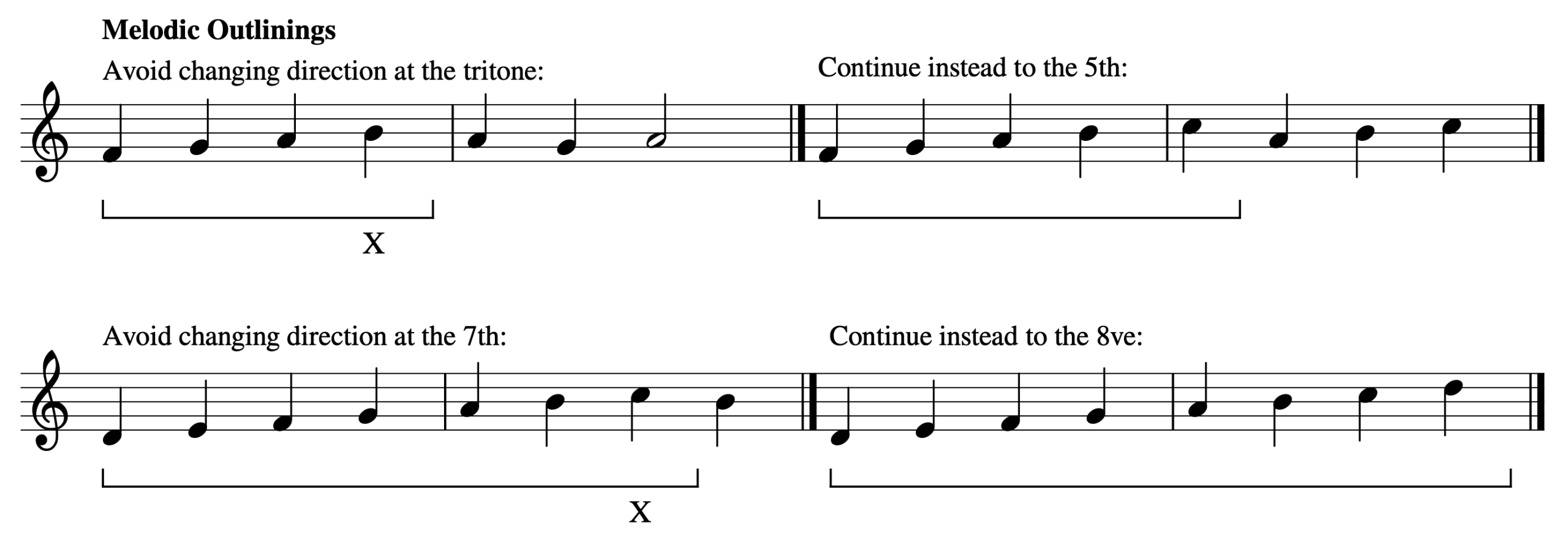

- Also avoid outlining (Example 4):

- an augmented interval

- a diminished interval

- any seventh

Harmonic writing (vertical intervals and the combination of parts)

- The first interval should be a perfect unison, fifth, or octave, and the last interval should be a perfect unison or octave (not fifth).

- Restrict the gap between parts to a twelfth (compound fifth) maximum, and to an octave for the most part.

- Avoid "overlapping" parts (where the nominally "upper" part goes below the "lower" one).

- Make sure to avoid:

- parallel octaves: when two parts start an octave apart and both move in the same direction by the same interval to also end an octave apart

- parallel fifths: when two parts start an perfect fifth apart and both move in the same direction by the same interval to also end a perfect fifth apart

- Also try to avoid:

- direct fifths and octaves: when two parts begin any interval apart and move in the same direction to a perfect fifth or octave

- unisons at any point in the exercise other than the first and last intervals

The Psychology of Counterpoint

The chapters on species counterpoint will not involve a specific style (classical, baroque, romantic, pop/rock, etc.). Instead, these exercises will set aside important musical elements like orchestration, melodic motives, formal structure, and even many elements of harmony and rhythm, in order to focus very specifically on a small set of fundamental musical problems. These fundamental problems are closely related to how some basic principles of auditory perception and cognition (i.e., how the brain perceives and conceptualizes sound) play out in Western musical structure.

For example, our brains tend to assume that sounds similar in pitch or timbre come from the same source. Our brains also listen for patterns, and when a new sound continues or completes a previously heard pattern, we typically assume that the new sound belongs together with those others. This is related to some of the most deep-seated, fundamental parts of our human experience, and even evolution. Hearing a regular pattern typically indicates a predictable (and safe) environment, while any change can signal danger and will tend to heighten our attention to the source. This system for directing attention (and adrenaline) where it is most likely to be needed has been essential to the survival of the human species. While listening to music in the 21st century does not (usually!) require us to listen out for animal predators, some part of that evolutionary experience is "hard-wired" into the psychology of human listening, and it has a role in what gives music its emotional effect—even in a safe environment.

For Western listeners, music that simply makes it easy for the brain to parse and process sound is boring—it calls for no heightened attention; it doesn’t increase our heart rate, make the hair on the back of our neck stand up, or give us a little jolt of dopamine. On the other hand, music that constantly activates our innate sense of danger is hardly pleasant for most listeners. That being the case, a balance between tension and relaxation, motion and rest, is fundamental to most of the music we will study.

The study of counterpoint helps us to engage several important musical “problems” in a strictly limited context, so that we can develop composition and analytical skills that can then be applied widely. Those problems arise as we seek to bring the following traits together:

- smooth, independent melodic lines

- tonal fusion (the preference for simultaneous notes to form a consonant unity)

- variety

- motion (towards a goal)

These traits are based in human perception and cognition, but they are often in conflict in specific musical moments and need to be balanced over the course of larger passages and complete works. Counterpoint will help us begin to practice working with that balance.

Finally, despite abstractions, it's still best to treat counterpoint exercises as miniature compositions and to perform them—vocally and instrumentally, and with a partner where possible—so that the ear, the fingers, the throat, and ultimately the mind can internalize the sound, sight, and feel of how musical lines work and combine.

- Huron, David. 2006. Sweet Anticipation: Music and the Psychology of Expectation. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Cantus firmus A (.pdf, .mscx). Asks students to critique one cantus firmus and write their own.

- Cantus firmus B (.pdf, .mscx). Asks students to critique one cantus firmus and write their own.

- For the complete set of Fux exercises, see the Gradus ad Parnassum chapter.

Key Takeaways

- Historically (in the 17th and 18th centuries) musicians and composers use figured bass to imply harmonies in ensemble works. Figured bass refers to the bass voice, under which figures and other symbols indicate implied harmonies.

- Figured bass is not usually added to chord symbols; however, it is added to triadic shorthand notation.

- It is called realizing figured bass when musicians turn figured bass into chords, either on paper or in performance.

- Triads and seventh chords have figures which correspond to root position and inverted harmonies when realized. Full figures are often abbreviated.

- In order to denote chromatic alterations to notes, musicians put accidentals (♭, ♯, ♮) before the figure that is altered. Musicians also use slashes through a figure or a plus sign before a figure, in order to indicate raising the note by a half step.

- Orphaned accidentals (accidentals which do not appear alongside a number) apply to the third above the bass.

- Horizontal lines indicate a change of note above a given bass, or a change in harmony.

- Figures are sometimes paired with Roman numerals to provide more information to music analysts.

In the 17th and 18th centuries, paper and ink were somewhat expensive materials. To save money--and also time--composers and musicians sometimes implied harmonies in ensemble works, without writing them out fully. Figured bass refers to the the bass voice or part, under which figures and other symbols indicate to musicians the implied harmony.[1]

Triadic Figures

Figured bass uses Arabic numerals and some symbols which indicate intervals above the bass note, which are then interpreted as chords by musicians. Example 1 shows the full figured bass for triads, as well as chord symbols for the same harmonies:

Example 1. The full figured bass for triads, as well as chord symbols.

As you can see in Example 1, a root position triad has a third and a fifth above the bass (indicated by "[latex]\begin{smallmatrix}5\\3\end{smallmatrix}[/latex]"). A first inversion triad has a third and a sixth above the bass (indicated by "[latex]\begin{smallmatrix}6\\3\end{smallmatrix}[/latex]"), and a second inversion triad has a fourth and a sixth above the bass (indicated by "[latex]\begin{smallmatrix}6\\4\end{smallmatrix}[/latex]"). In figured bass, larger numbers always appear above smaller ones.

In order to save even more time (and more paper space!), composers and musicians abbreviated the full figured bass for triads and seventh chords. Example 2 shows the abbreviated figured bass for triads that we usually use today, as well as their chord symbols:

Example 2. The abbreviated figured bass for triads.

As you can see, no figure appears for root position. The superscript number "6" will result in a first inversion triad, while a second inversion triad keeps its full figures, "[latex]\begin{smallmatrix}6\\4\end{smallmatrix}[/latex]," to distinguish it from a first inversion triad.

Figured bass is not usually added to chord symbols; however, it is added to triadic shorthand notation. For example, the last measure of example 2 would be notated as "A/E" in chord symbols. Using triadic shorthand, this chord would be notated as "A[latex]\begin{smallmatrix}6\\4\end{smallmatrix}[/latex]."

When musicians turn figured bass into chords—either on paper or in performance—this is called realizing the figured bass. Example 3 shows the process of realization for several triads:

Example 3 Some triads with figured bass and their realizations.

As seen in the first measure of Example 3, an E♭ appears with no figured bass next to it. Therefore, we can assume that we are realizing an E♭ major triad in root position. This chord is realized (written out with notes) in the next measure. In measure 3, we see the figure "6" below the bass note G. We can understand that notation to mean that we are realizing a sixth and a third above the bass note G. This chord is realized in the next measure (an E♭ major triad in first inversion). In measure 5, we see the figures "[latex]\begin{smallmatrix}6\\4\end{smallmatrix}[/latex]" below the bass note B♭. This notation means that we are realizing a sixth and a fourth above the bass note B♭. This chord is realized in the next measure (an E♭ major triad in second inversion).

Seventh Chord Figures

Example 4 shows the full figured bass for seventh chords, as well as chord symbols for the same harmonies:

Example 4. The full figured bass for seventh chords, as well as chord symbols.

As you can see in the full figures of Example 4, a root position seventh chord has a third, fifth, and seventh above the bass. A first inversion seventh chord has a third, fifth, and sixth above the bass, while a second inversion seventh chord has a third, fourth, and sixth above the bass. Finally, a third inversion seventh chord has a second, fourth, and sixth above the bass.

Example 5 shows the abbreviated figured bass for seventh chords that musicians use today underneath their chord symbols:

Example 5. The abbreviated figures for seventh chords.

As seen in Example 5, a root position seventh chord is abbreviated with the superscript number "7" while the figures "[latex]^6_5[/latex]" will result in a first inversion seventh chord. A second inversion seventh chord is indicated by the figures "[latex]^4_3[/latex]" and the figures "[latex]^4_2[/latex]" will result in a third inversion seventh chord. Sometimes, in older style figured bass notation, a third inversion seventh chord is notated simply as a superscript "2."

You can realize figured bass for inverted seventh chords in a similar way to how you realized them for triads. To realize an inverted seventh chord, simply write the indicated intervals above the bass note, keeping in mind that the full figures are usually abbreviated. Example 6 shows the process of realization for several seventh chords:

Example 6. Some seventh chords with figured bass and their realizations.

As seen in the first measure of Example 6, an A appears with the superscript figure "7" under it. Therefore, we can assume that we are realizing an A dominant seventh chord in root position. This chord is realized (written out with notes) in the next measure. In measure 3, we see the figures "[latex]^6_5[/latex]" below the bass note C♯. We can understand that notation to mean that we are realizing a sixth, fifth, and third above the bass note C♯. This chord is realized in the next measure (resulting in an A dominant seventh chord in first inversion). In measure 5, we see the figures "[latex]^4_3[/latex]" below the bass note E. This notation means that we are realizing a sixth, fourth, and third above the bass note E. This chord is realized in the next measure (resulting in an A dominant seventh chord in second inversion). In measure 7, we see the figures "[latex]^4_2[/latex]" below the bass note G. This means that we are realizing a sixth, fourth, and second above the bass note G. This chord is realized in the next measure (resulting in an A dominant seventh chord in third inversion).

Other Figured Bass Symbols

In order to denote chromatic alterations to notes, musicians put accidentals (♭, ♯, ♮) before the figure that is altered. Example 7 shows a few realizations of figures with accidentals:

Example 7. Realizations of figures with accidentals.

So, for instance, in Example 7, the flat sign before the 6 indicates that the 6th above the bass note is lowered by a half step, changing the pitch from a B natural to a B♭, and the natural before the the 3 indicates that the 3rd above the bass note has been lowered by a half step, changing the pitch from an F# indicated by the key signature to an F natural.

Musicians also use slashes through a figure or a plus sign before a figure, in order to indicate raising the note by a half step. These symbols and their realizations are shown in Example 8:

Example 8. Realization of figures with a slash and a plus sign.

An orphaned accidental (or hanging accidental) is also common. These are accidentals that appear by themselves, and may or may not be accompanied by other figures or symbols. In these cases, the accidental is assumed to apply to the third above the bass, as seen in Example 9:

Example 9. Realization of orphaned accidentals.

There is one other symbol that is commonly seen in figured bass. Horizontal lines indicate a change of note above the given bass, or a change of harmony. Example 10 shows several realizations of figures with horizontal lines:

Example 10. Realization of figures with horizontal lines.

In the first measure of Example 10, the horizontal line indicates a change of note above the given bass. We could read this as "a fifth above the bass moves to a sixth above the bass," as realized in measure 2. Sometimes this indicates a suspension, which you can read more about in Embellishing Tones. You can see an example of a suspension in measures 3 and 4 above; this could be read as "a fourth above the bass moves to a third above the bass." Horizontal lines can also indicate a cadential [latex]^6_4[/latex] chord, which you can read more about in Strengthening Endings with Cadential 6/4. You can see an example of a cadential [latex]^6_4[/latex] in measures 5 and 6 above; this could be read as "a sixth above the bass moves to a fifth above the bass," and "a fourth above the bass moves to a third above the bass." As you can see in measures 5 and 6 of Example 10, more than one horizontal line can appear at the same time in figured bass. Horizontal lines can also indicate a change in harmony, as seen in measures 7 and 8 above; this could be read as "a chord with a sixth above the bass moves to a chord with a fifth above the bass," since it is the bass itself which is moving.

Roman Numerals and Figures

Roman numerals are often paired with figures to denote chord inversions and certain embellishments. For example, a superscript "6" figure could be paired with the Roman numeral "I" to represent a tonic triad in first inversion, and the figures "[latex]^4_3[/latex]" would indicate a second inversion dominant seventh chord when paired with the Roman numeral "V." However, not all instructors use figures with Roman numerals, so you'll only want to do this if your instructor has indicated that you should. Example 11 shows a few realized Roman numerals with figures:

Example 11. Realization of Roman numerals with figures.

In this class, figures will be used with Roman numerals as shown in Example 11.

The table below is a summary of the different types of symbols commonly used for figured bass.

| Complete figured bass symbol | [latex]^5_3[/latex] | [latex]^6_3[/latex] | [latex]^6_4[/latex] | 7

5 3 |

6

5 3 |

6

4 3 |

6

4 2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Symbol most often used | none | 6 | [latex]^6_4[/latex] | 7 | [latex]^6_5[/latex] | [latex]^4_3[/latex] | [latex]^4_2[/latex] |

| Indicates | root position triad | first inversion triad | second inversion triad | root position seventh chord | first inversion seventh chord | second inversion seventh chord | third inversion seventh chord |

| Symbol | How it is used |

|---|---|

| ♭, ♯, ♮ | A sharp, flat or natural that is not alongside a number indicates that the third interval above the bass note should be sharped, flatted or naturaled. |

| 6 6 6

♭, ♯, ♮ |

A sharp, flat or natural below a 6 indicates a first inversion triad with the third above the bass sharped, flatted or naturaled. |

| ♭6, ♯6, ♮6 | A sharp, flat or natural on either side of a number indicates that that interval above the bass (in this example a "6") should be sharped, flatted or naturaled. |

| A slash on any number indicates that that interval above the bass should be raised a half step. Sometimes there will be a plus sign (+) instead of a slash. |

- Figured Bass Inversion Symbols (Robert Hutchinson)

- Figured Bass: How to Read Chord Inversion Symbols (LANDR)

- Figured Bass (thinking music.ca)

- Figured Bass Notation: Tutorial (Iowa State University)

- Figured Bass (Andre Mount)

- How to Realize a Figured Bass (Robert Kelley)

- Figured Bass Symbols (Robert Kelley)

- Realizing Figured Bass Chords, I (.pdf)

- Realizing Roman Numerals with Figured Bass (website), pp. 2, 5 (.pdf), p. 11 (.pdf)

- Writing Roman Numerals and Figures for Bass Lines with Figured Bass, II and VII (.pdf), pp. 1, 3, 4 (.pdf), p. 11 (.pdf)

- Triadic Figures (.pdf, .mcsz). Asks students to write chord symbols and identify the inversion of closed-position chords, and to realize chords from chord-symbol-and-figured-bass notation.

- Seventh Chord Figures (.pdf, .mcsz) Asks students to write chord symbols and identify the inversion of closed-position chords, and to realize chords from chord-symbol-and-figured-bass notation.

The materials in this chapter come from Open Music Theory, with the exception of the tables of figured bass symbols, added by Elizabeth Pauly.

A note value that lasts half the duration of a quarter note, or the duration of two sixteenth notes.

A subphrase that harmonizes the core bass pattern mi–fa–sol–do (3̂–4̂–5̂–1̂). Functions similarly to a continuation.

Key Takeaways

- Nonharmonic tones can be grouped into three categories (summarized in Example 13):

- Involving only stepwise motion: passing tone, neighbor tone

- Involving a leap: appoggiatura, escape tone

- Involving static notes: suspension, retardation, pedal, anticipation

Overview

One of the tools that composers use to make music more interesting is the nonharmonic tone. A nonharmonic tone is a pitch that is added to a composition that is not part of the surrounding chord. The nonharmonic tone creates dissonance which in turn creates momentary musical tension - a really cool effect. In this chapter you will learn about the various different kinds of nonharmonic tones and how they work, and begin to learn how to find them within their musical context.

How to Find a Nonharmonic Tone

One of the most challenging aspects of learning about nonharmonic tones is learning how to spot them. Once you have spotted the nonharmonic tone, it becomes much simpler to discern what type of nonharmonic tone it is, as the options are fairly limited. The tutorial embedded below, "Desperately Seeking Nonharmonic Tones" is designed to help you build this skill.

Passing tones, neighbor tones: Nonharmonic tones that move by step

Example 1 showed the two kinds of embellishing tones that move by step: passing tones (PTs) and neighbor tones (NTs). Passing tones are approached by step and left by step in the same direction, either ascending or descending (Example 3). Neighbor tones are approached by step and left by step in the opposite direction, producing either an upper neighbor or a lower neighbor (Example 4).

Example 3. Passing tones in a two-voice texture, (a) ascending and (b) descending.

Example 4. (a) Upper neighbor and (b) lower neighbor tones in a two-voice texture.

Appoggiaturas and escape tones: Embellishing tones that involve a leap

Examples 5 and 6 show the two kinds of embellishing tones that involve a leap: appoggiaturas (APPs) and escape tones (ETs). Appoggiaturas are approached by leap and left by step in the opposite direction (Example 7). The appoggiatura typically occurs on a stronger part of the beat than its surrounding notes. Escape tones are approached by step and left by leap in the opposite direction (Example 8). The escape tone typically occurs on a weaker part of the beat than its surrounding notes. It is more common for appoggiaturas and escape tones to be left by motion downward (Examples 7a and 8a) than upward (7b and 8b).

Example 5. An appoggiatura in Joseph Boulogne, String Quartet no. 4, I, mm. 5–9 (0:09-0:19).

Example 6. An escape tone in Margaret Casson, "The Cuckoo."

Example 7. Appoggiaturas in a two-voice texture.

Example 8. Escape tones in a two-voice texture.

Suspensions, anticipations, and pedal tones: Embellishing tones involving static notes

Examples 9–11 show three of the four kinds of embellishing tones that involve static notes (i.e., notes that don't move): suspensions (SUS), retardations (RET), and pedal tones (PED). A fourth kind of embellishing tone, the anticipation, deserves special comment below.

Suspensions are approached by a static note and left by step down, while retardations are approached by a static note and left by step up (Examples 9 and 10). Both suspensions and retardations are always on a stronger part of the beat than the surrounding notes. (Suspensions are discussed in greater detail in the chapter on fourth species counterpoint.)

Pedal tones are often found in the bass. They consist of a series of static notes below chord changes that do not include the bass. We typically label them using the scale degree number of the pedal note, as in Example 11.

Example 9. Suspensions and a retardation in Joseph Boulogne's String Quartet no. 4, I, mm. 47–49 (1:30–1:36).

Example 10. (a) Suspension and (b) retardation in a two-voice texture.

Example 11. Pedal tone in Josephine Lang's "Dem Königs-Sohn," mm. 16–18.

Like the suspension, retardation, and pedal tone, anticipations also involve static notes. But anticipations are a two-note (rather than three-note) gesture, in which a chord tone is heard early as a non-chord tone (Example 12). In other words, it “anticipates” its upcoming membership in a chord.

Example 12. An anticipation in Josephine Lang's "Erinnerung," mm. 29–30 (1:54–1:59).

Summary

The table in Example 13 provides a summary of the embellishing tones covered in this chapter.

[table “41” not found /]

Example 13. Summary of embellishing tones.

- Embellishing tones (.pdf, .mscz). Asks students to write embellishing tones in a two-voice texture and label embellishing tones in an excerpt. Worksheet recording

The elliptical part of the note. Can be either filled in (black) or outlined (white).

A vertical line that originates at the notehead, used to indicate rhythm and voicing.

A vertical line that originates at the notehead, used to indicate rhythm and voicing.

The horizontal lines that connect certain groups of notes together.

A physical and/or social setting.