47 Strengthening Endings with V⁷

John Peterson

Key Takeaways

- This chapter introduces how composers add a seventh to the dominant to strengthen its pull toward the tonic. There are three ways a V7 can resolve to tonic:

- The default resolution: where all active notes resolve according to their tendencies.

- Incomplete V7: where the fifth is omitted from the V7 and the V7‘s root is doubled instead to create a complete tonic.

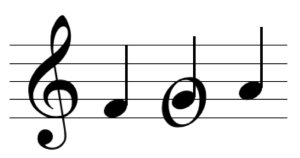

- Leading-tone drop: where the leading tone in a complete V7 leaps down to sol (

) to create a complete tonic.

) to create a complete tonic.

The phrase in Example 1 ends with a perfect authentic cadence (PAC) similar to those we saw and wrote in the Introduction to Harmony, Cadences, and Endings chapter. Here, however, the V chord contains an extra note, fa (![]() ), that transforms it from a major triad into a dominant seventh chord. Since the seventh adds dissonance (and therefore instability) to the chord, it strengthens the pull of the V chord toward I. Compare the sound of the excerpts in Example 2.

), that transforms it from a major triad into a dominant seventh chord. Since the seventh adds dissonance (and therefore instability) to the chord, it strengthens the pull of the V chord toward I. Compare the sound of the excerpts in Example 2.

https://musescore.com/user/32728834/scores/6224806/embed

Example 1. A PAC involving V7 in Margaret Casson’s The Cuckoo

https://musescore.com/user/32728834/scores/6224809/embed

Example 2. A PAC involving: (a) only triads and (b) a V7 chord.

The Default Resolution of V7 to I

When the notes of a complete V7 chord resolve according to their typical tendencies, we end up with a tonic triad that has three roots and one third—no fifth (Examples 3a and 3b). This is a completely normal, expected, and common resolution of V7 to I. It’s okay to leave out the fifth here since it doesn’t provide essential information about the chord. By contrast, the root and third are essential: the root determines the chord’s name, and the third determines its quality.

The resolution in Example 3c, where re (![]() ) goes up to mi (

) goes up to mi (![]() ), is very uncommon, and such an unusual doubling in the tonic chord (two roots, two thirds) usually leads to voice-leading problems. We suggest avoiding this kind of resolution.

), is very uncommon, and such an unusual doubling in the tonic chord (two roots, two thirds) usually leads to voice-leading problems. We suggest avoiding this kind of resolution.

https://musescore.com/user/32728834/scores/6224872/embed

Example 3. Default resolution of V7.

To resolve V7 to I using a default resolution:

- Write the entire bass: sol to do (

–

– )

) - Write the entire soprano by choosing an active note to place in the soprano over V7, then resolving that note according to its tendency. Example 4 shows the tendencies for active notes in V7.

- If you are writing in minor, remember to use ti (

), not te (

), not te ( ) in V7 to make the chord major!

) in V7 to make the chord major!

- If you are writing in minor, remember to use ti (

- Fill in the inner voices by asking “what do I have, what do I need, and what is the tendency of those notes?”

[table “38” not found /]

Example 4. Tendencies of active notes in V7.

Alternative Resolutions of V7 to I

Sometimes a composer may want the tonic chord to be complete rather than the incomplete chord that occurs in the default resolution. Two alternative resolutions of V7 make it possible to create a complete I. Note that the steps for writing remain the same as for the default resolution: write the entire bass, write the entire soprano choosing an active note over V7, then fill in the inner voices together as a pair by asking “what do I have, what do I need, and where do those notes go?”

Incomplete V7

Examples 5a and 5b show a resolution where the fifth has been omitted from the V7, allowing that chord to resolve to a complete I. When we omit the fifth, we need to select a note to double in order to retain our four-voice texture. The only note we can double is the root, since doubling ti (![]() ) or fa (

) or fa (![]() ) would create parallel octaves when both voices resolve according to their tendencies (Examples 5c and 5d).

) would create parallel octaves when both voices resolve according to their tendencies (Examples 5c and 5d).

https://musescore.com/user/32728834/scores/6224803/embed

Example 5. Alternative resolution of V7 involving an incomplete V7.

Leading-Tone Drop

It’s also possible to create a complete I from a complete V7, but in order to do so, we have to allow a tendency tone to move somewhere other than its expected resolution. Example 6 shows how this is possible using a leading-tone drop. [1] Here, ti (![]() ) drops down to sol (

) drops down to sol (![]() ) in an inner voice. This works because: (1) ti (

) in an inner voice. This works because: (1) ti (![]() ) is not a dissonant note; (2) ti (

) is not a dissonant note; (2) ti (![]() ) is in an inner voice, so it’s not too noticeable; and (3) ti (

) is in an inner voice, so it’s not too noticeable; and (3) ti (![]() ) is the closest note that can move to sol (

) is the closest note that can move to sol (![]() ) in the tonic without causing parallels.

) in the tonic without causing parallels.

https://musescore.com/user/32728834/scores/6224804/embed

Example 6. Alternative resolution of V7 involving a leading-tone drop.

Two things are worth emphasizing here:

- Use the leading-tone drop only in the alto or tenor voice to hide the fact that it’s not resolving as expected.

- The leading tone always leaps down to sol (

), never to mi (

), never to mi ( ), which is further away than sol (

), which is further away than sol ( ).

).

Summary

Example 7 summarizes the three possible ways to resolve V7–I. You may notice that we have not discussed how V7 works in half cadences (HCs). V7 is much less common in a HC since the HC is already unstable, and adding a seventh makes it that much more unstable. Since such a cadence more often appears in Romantic music, Janet Schmalfeldt (2011, 202) has termed HCs involving V7 the “19th-century HC.”

https://musescore.com/user/32728834/scores/6224814/embed

Example 7. A summary of possible resolutions of V7.

- Schmalfeldt, Janet. 2011. In the Process of Becoming: Analytic and Philosophical Perspectives on Form in Early Nineteenth-Century Music. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Strengthening Endings with V7 (.pdf, .docx, spotify playlist). Asks students to write and resolve V7 chords and provide analysis of cadences in select passages.

- This is a term we first heard from Nancy Rogers at Florida State University. Some people describe this phenomenon as a "frustrated leading tone," but we believe that "leading-tone drop" better describes the technique. ↵

Key Takeaways

- Nonharmonic tones can be grouped into three categories:

- Involving only stepwise motion: passing tone, neighbor tone

- Involving a leap: appoggiatura, escape tone

- Involving static notes: suspension, retardation, pedal, anticipation

Overview

One of the tools that composers use to make music more interesting is the nonharmonic tone. Nonharmonic tones are pitches that are added to a composition that are not part of the surrounding chord. The nonharmonic tone creates dissonance which in turn creates momentary musical tension - a really cool effect. In this chapter you will learn about the various different kinds of nonharmonic tones and how they work, and learn how to identify them within a musical context.

How to Spot a Nonharmonic Tone

One of the most important skills to develop when working with nonharmonic tones is learning how to identify them. Once you have located a nonharmonic tone, it becomes much easier to determine its type, as the possibilities are fairly limited. The tutorial embedded below, “Desperately Seeking Nonharmonic Tones,” gives you an opportunity to practice finding nonharmonic tones in a musical selection with simple harmony.

Types of Nonharmonic Tones

In this next section we will explore the various types of nonharmonic tones, sometimes called "embellishing tones" or "non-chord tones". These terms all mean the same thing.

Passing tones, neighbor tones: Nonharmonic tones that move by step

Example 1 showed the two kinds of embellishing tones that move by step: passing tones (PTs) and neighbor tones (NTs). Passing tones are approached by step and left by step in the same direction, either ascending or descending (Example 3). Neighbor tones are approached by step and left by step in the opposite direction, producing either an upper neighbor or a lower neighbor (Example 4).

Passing tones by openmusictheory

Example 1. Passing tones in a two-voice texture, (a) ascending and (b) descending.

Neighbor Tones by openmusictheory

Example 2. (a) Upper neighbor and (b) lower neighbor tones in a two-voice texture.

Double Neighbor Tones or Changing Tones

Double neighbor tones (DNT) (sometimes called "neighbor group" or changing tone (CT)) are made of two nonharmonic tones in a row. The first moves by step away from a chord tone, then skips to another nonharmonic tone, then moves by step to another chord tone, frequently the same chord tone.

Appoggiaturas and escape tones: Nonharmonic tones that involve a leap

Appoggiaturas (APPs) and escape tones (ETs) involve either a skip or a leap. Appoggiaturas are approached by skip or leap and left by step in the opposite direction (Example 3). The appoggiatura typically occurs on a stronger part of the beat than its surrounding notes. Escape tones are approached by step and left by skip or leap in the opposite direction (Example 4). The escape tone typically occurs on a weaker part of the beat than its surrounding notes. It is more common for appoggiaturas and escape tones to be left by motion downward (Examples 3a and 4a) than upward (3b and 4b).

Appoggiatura by openmusictheory

Example 3. Appoggiaturas in a two-voice texture.

Escape Tones by openmusictheory

Example 4. Escape tones in a two-voice texture.

Examples 5 and 6 show the two kinds of embellishing tones that involve a leap: appoggiaturas and escape tones.

Joseph Boulogne, String Quartet No. 4, I, mm. 5-9 by openmusictheory

Example 5. An appoggiatura in Joseph Boulogne, String Quartet no. 4, I, mm. 5–9 (0:09-0:19).

ETs in Casson The Cuckoo by openmusictheory

Example 6. An escape tone in Margaret Casson, "The Cuckoo."

Suspensions, retardations, anticipations, and pedal tones: Nonharmonic tones involving static notes

There are four kinds of embellishing tones that involve static notes (i.e., notes that don't move): suspensions (SUS), retardations (RET), pedal tones (PED) and anticipations (ANT)

Suspensions and Retardations

Suspensions are approached by a static note and left by step down, while retardations are approached by a static note and left by step up. They follow a similar pattern:

Preparation-->Suspension (or retardation)-->Resolution

Suspensions are indicated in Roman numeral analysis not only by their abbreviations, but by the simplified intervals of the suspension and the resolution above the bass note. Retardations do not need to be labeled with the intervals above the bass note.

- 9-8. 7-6 and 4-3 suspensions are above the bass voice.

- 2-3 suspensions are in the bass voice.

- Both suspensions and retardations are always on a stronger part of the beat than the surrounding notes.

Why are all suspensions in the bass voice called 2-3 suspensions?

There is a pattern to the numbers used when the suspension is in an upper voice – the second number is always one less than the first number – 9-8, 7-6, 4-3. This is because the intervallic relationship between the upper notes and the bass voice gets smaller as the suspension resolves down by step (and closer to the bass). However, when the suspension is in the bass, the suspended note must still move down, making the resolution note farther away from all of the upper voices. This means the suspended note is closer to the upper notes, and the resolution is farther away, meaning that the intervallic relationship gets bigger. We use the numbers 2-3 because there will always be a 2-3 relationship between the suspension and resolution in the bass and one of the upper voices.

The fourth suspension in Example 7 demonstrates a 2-3 suspension. In this case the 2-3 relationship is between the bass and the "A" in the soprano voice.

Example 7 below illustrates how the melodic pattern of Preparation-->Suspension-->Resolution works, and the intervallic relationships of the various suspensions and resolutions to the bass voice.

Example 7. 9-8, 7-6, 4-3 and 2-3 suspensions.

Example 8 provides a few examples of retardations.

Example 8. Retardations by empauly

Pedal Tones

Pedal tones are often found in the bass. They consist of a series of static notes below chord changes that do not include the bass. We typically label them using the scale degree number of the pedal note, as in Example 8.

Josephine Lang, Dem Konigs-Sohn, mm. 16-18 by openmusictheory

Like the suspension, retardation, and pedal tone, anticipations also involve static notes. But anticipations are a two-note (rather than three-note) gesture, in which a chord tone is heard early as a non-chord tone (Example 9). In other words, it “anticipates” its upcoming membership in a chord.

Embellishing_Tones_ex.9.mscz by openmusictheory

Example 9. An anticipation in Josephine Lang's "Erinnerung," mm. 29–30 (1:54–1:59).

Summary

The table in Example 13 provides a summary of the embellishing tones covered in this chapter.

| Embellishing Tone | Approached by | Left by | Direction | Additional Detail | Example |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Passing Tone (PT) | Step | Step | Same | May ascend or descend |  |

| Neighbor Tone (NT) | Step | Step | Opposite | Both upper and lower exist |  |

| Appoggiatura (APP) | Leap | Step | Opposite | Appoggiatura is usually on a strong part of the beat |  |

| Escape Tone (ET) | Step | Leap | Opposite | Escape tone is usually on a weaker part of the beat |  |

| Suspension (SUS) | Static note | Step | Down | Suspension is always on a stronger part of the beat |  |

| Retardation (RET) | Static note | Step | Up | Retardation is always on a stronger part of the beat |  |

| Pedal Tone (PED) | Static note | Static note | N/A |  |

|

| Anticipation (ANT) | N/A | Static note | N/A | The anticipation is usually on a weaker part of the beat |  |

Example 13. Summary of embellishing tones.

- Embellishing tones (.pdf, .mscz). Asks students to write embellishing tones in a two-voice texture and label embellishing tones in an excerpt. Worksheet recording

Key Takeaways

- Historically (in the 17th and 18th centuries) musicians and composers use figured bass to imply harmonies in ensemble works. Figured bass refers to the bass voice, under which figures and other symbols indicate implied harmonies.

- Figured bass is not usually added to chord symbols; however, it is added to triadic shorthand notation.

- It is called realizing figured bass when musicians turn figured bass into chords, either on paper or in performance.

- Triads and seventh chords have figures which correspond to root position and inverted harmonies when realized. Full figures are often abbreviated.

- In order to denote chromatic alterations to notes, musicians put accidentals (♭, ♯, ♮) before the figure that is altered. Musicians also use slashes through a figure or a plus sign before a figure, in order to indicate raising the note by a half step.

- Orphaned accidentals (accidentals which do not appear alongside a number) apply to the third above the bass.

- Horizontal lines indicate a change of note above a given bass, or a change in harmony.

- Figures are sometimes paired with Roman numerals to provide more information to music analysts.

In the 17th and 18th centuries, paper and ink were somewhat expensive materials. To save money--and also time--composers and musicians sometimes implied harmonies in ensemble works, without writing them out fully. Figured bass refers to the the bass voice or part, under which figures and other symbols indicate to musicians the implied harmony.[1]

Triadic Figures

Figured bass uses Arabic numerals and some symbols which indicate intervals above the bass note, which are then interpreted as chords by musicians. Example 1 shows the full figured bass for triads, as well as chord symbols for the same harmonies:

Example 1. The full figured bass for triads, as well as chord symbols.

As you can see in Example 1, a root position triad has a third and a fifth above the bass (indicated by "[latex]\begin{smallmatrix}5\\3\end{smallmatrix}[/latex]"). A first inversion triad has a third and a sixth above the bass (indicated by "[latex]\begin{smallmatrix}6\\3\end{smallmatrix}[/latex]"), and a second inversion triad has a fourth and a sixth above the bass (indicated by "[latex]\begin{smallmatrix}6\\4\end{smallmatrix}[/latex]"). In figured bass, larger numbers always appear above smaller ones.

In order to save even more time (and more paper space!), composers and musicians abbreviated the full figured bass for triads and seventh chords. Example 2 shows the abbreviated figured bass for triads that we usually use today, as well as their chord symbols:

Example 2. The abbreviated figured bass for triads.

As you can see, no figure appears for root position. The superscript number "6" will result in a first inversion triad, while a second inversion triad keeps its full figures, "[latex]\begin{smallmatrix}6\\4\end{smallmatrix}[/latex]," to distinguish it from a first inversion triad.

Figured bass is not usually added to chord symbols; however, it is added to triadic shorthand notation. For example, the last measure of example 2 would be notated as "A/E" in chord symbols. Using triadic shorthand, this chord would be notated as "A[latex]\begin{smallmatrix}6\\4\end{smallmatrix}[/latex]."

When musicians turn figured bass into chords—either on paper or in performance—this is called realizing the figured bass. Example 3 shows the process of realization for several triads:

Example 3 Some triads with figured bass and their realizations.

As seen in the first measure of Example 3, an E♭ appears with no figured bass next to it. Therefore, we can assume that we are realizing an E♭ major triad in root position. This chord is realized (written out with notes) in the next measure. In measure 3, we see the figure "6" below the bass note G. We can understand that notation to mean that we are realizing a sixth and a third above the bass note G. This chord is realized in the next measure (an E♭ major triad in first inversion). In measure 5, we see the figures "[latex]\begin{smallmatrix}6\\4\end{smallmatrix}[/latex]" below the bass note B♭. This notation means that we are realizing a sixth and a fourth above the bass note B♭. This chord is realized in the next measure (an E♭ major triad in second inversion).

Seventh Chord Figures

Example 4 shows the full figured bass for seventh chords, as well as chord symbols for the same harmonies:

Example 4. The full figured bass for seventh chords, as well as chord symbols.

As you can see in the full figures of Example 4, a root position seventh chord has a third, fifth, and seventh above the bass. A first inversion seventh chord has a third, fifth, and sixth above the bass, while a second inversion seventh chord has a third, fourth, and sixth above the bass. Finally, a third inversion seventh chord has a second, fourth, and sixth above the bass.

Example 5 shows the abbreviated figured bass for seventh chords that musicians use today underneath their chord symbols:

Example 5. The abbreviated figures for seventh chords.

As seen in Example 5, a root position seventh chord is abbreviated with the superscript number "7" while the figures "[latex]^6_5[/latex]" will result in a first inversion seventh chord. A second inversion seventh chord is indicated by the figures "[latex]^4_3[/latex]" and the figures "[latex]^4_2[/latex]" will result in a third inversion seventh chord. Sometimes, in older style figured bass notation, a third inversion seventh chord is notated simply as a superscript "2."

You can realize figured bass for inverted seventh chords in a similar way to how you realized them for triads. To realize an inverted seventh chord, simply write the indicated intervals above the bass note, keeping in mind that the full figures are usually abbreviated. Example 6 shows the process of realization for several seventh chords:

Example 6. Some seventh chords with figured bass and their realizations.

As seen in the first measure of Example 6, an A appears with the superscript figure "7" under it. Therefore, we can assume that we are realizing an A dominant seventh chord in root position. This chord is realized (written out with notes) in the next measure. In measure 3, we see the figures "[latex]^6_5[/latex]" below the bass note C♯. We can understand that notation to mean that we are realizing a sixth, fifth, and third above the bass note C♯. This chord is realized in the next measure (resulting in an A dominant seventh chord in first inversion). In measure 5, we see the figures "[latex]^4_3[/latex]" below the bass note E. This notation means that we are realizing a sixth, fourth, and third above the bass note E. This chord is realized in the next measure (resulting in an A dominant seventh chord in second inversion). In measure 7, we see the figures "[latex]^4_2[/latex]" below the bass note G. This means that we are realizing a sixth, fourth, and second above the bass note G. This chord is realized in the next measure (resulting in an A dominant seventh chord in third inversion).

Other Figured Bass Symbols

In order to denote chromatic alterations to notes, musicians put accidentals (♭, ♯, ♮) before the figure that is altered. Example 7 shows a few realizations of figures with accidentals:

Example 7. Realizations of figures with accidentals.

So, for instance, in Example 7, the flat sign before the 6 indicates that the 6th above the bass note is lowered by a half step, changing the pitch from a B natural to a B♭, and the natural before the the 3 indicates that the 3rd above the bass note has been lowered by a half step, changing the pitch from an F# indicated by the key signature to an F natural.

Musicians also use slashes through a figure or a plus sign before a figure, in order to indicate raising the note by a half step. These symbols and their realizations are shown in Example 8:

Example 8. Realization of figures with a slash and a plus sign.

An orphaned accidental (or hanging accidental) is also common. These are accidentals that appear by themselves, and may or may not be accompanied by other figures or symbols. In these cases, the accidental is assumed to apply to the third above the bass, as seen in Example 9:

Example 9. Realization of orphaned accidentals.

There is one other symbol that is commonly seen in figured bass. Horizontal lines indicate a change of note above the given bass, or a change of harmony. Example 10 shows several realizations of figures with horizontal lines:

Example 10. Realization of figures with horizontal lines.

In the first measure of Example 10, the horizontal line indicates a change of note above the given bass. We could read this as "a fifth above the bass moves to a sixth above the bass," as realized in measure 2. Sometimes this indicates a suspension, which you can read more about in Embellishing Tones. You can see an example of a suspension in measures 3 and 4 above; this could be read as "a fourth above the bass moves to a third above the bass." Horizontal lines can also indicate a cadential [latex]^6_4[/latex] chord, which you can read more about in Strengthening Endings with Cadential 6/4. You can see an example of a cadential [latex]^6_4[/latex] in measures 5 and 6 above; this could be read as "a sixth above the bass moves to a fifth above the bass," and "a fourth above the bass moves to a third above the bass." As you can see in measures 5 and 6 of Example 10, more than one horizontal line can appear at the same time in figured bass. Horizontal lines can also indicate a change in harmony, as seen in measures 7 and 8 above; this could be read as "a chord with a sixth above the bass moves to a chord with a fifth above the bass," since it is the bass itself which is moving.

Roman Numerals and Figures

Roman numerals are often paired with figures to denote chord inversions and certain embellishments. For example, a superscript "6" figure could be paired with the Roman numeral "I" to represent a tonic triad in first inversion, and the figures "[latex]^4_3[/latex]" would indicate a second inversion dominant seventh chord when paired with the Roman numeral "V." However, not all instructors use figures with Roman numerals, so you'll only want to do this if your instructor has indicated that you should. Example 11 shows a few realized Roman numerals with figures:

Example 11. Realization of Roman numerals with figures.

In this class, figures will be used with Roman numerals as shown in Example 11.

The table below is a summary of the different types of symbols commonly used for figured bass.

| Complete figured bass symbol | [latex]^5_3[/latex] | [latex]^6_3[/latex] | [latex]^6_4[/latex] | 7

5 3 |

6

5 3 |

6

4 3 |

6

4 2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Symbol most often used | none | 6 | [latex]^6_4[/latex] | 7 | [latex]^6_5[/latex] | [latex]^4_3[/latex] | [latex]^4_2[/latex] |

| Indicates | root position triad | first inversion triad | second inversion triad | root position seventh chord | first inversion seventh chord | second inversion seventh chord | third inversion seventh chord |

| Symbol | How it is used |

|---|---|

| ♭, ♯, ♮ | A sharp, flat or natural that is not alongside a number indicates that the third interval above the bass note should be sharped, flatted or naturaled. |

| 6 6 6

♭, ♯, ♮ |

A sharp, flat or natural below a 6 indicates a first inversion triad with the third above the bass sharped, flatted or naturaled. |

| ♭6, ♯6, ♮6 | A sharp, flat or natural on either side of a number indicates that that interval above the bass (in this example a "6") should be sharped, flatted or naturaled. |

| A slash on any number indicates that that interval above the bass should be raised a half step. Sometimes there will be a plus sign (+) instead of a slash. |

- Figured Bass Inversion Symbols (Robert Hutchinson)

- Figured Bass: How to Read Chord Inversion Symbols (LANDR)

- Figured Bass (thinking music.ca)

- Figured Bass Notation: Tutorial (Iowa State University)

- Figured Bass (Andre Mount)

- How to Realize a Figured Bass (Robert Kelley)

- Figured Bass Symbols (Robert Kelley)

- Realizing Figured Bass Chords, I (.pdf)

- Realizing Roman Numerals with Figured Bass (website), pp. 2, 5 (.pdf), p. 11 (.pdf)

- Writing Roman Numerals and Figures for Bass Lines with Figured Bass, II and VII (.pdf), pp. 1, 3, 4 (.pdf), p. 11 (.pdf)

- Triadic Figures (.pdf, .mcsz). Asks students to write chord symbols and identify the inversion of closed-position chords, and to realize chords from chord-symbol-and-figured-bass notation.

- Seventh Chord Figures (.pdf, .mcsz) Asks students to write chord symbols and identify the inversion of closed-position chords, and to realize chords from chord-symbol-and-figured-bass notation.

The materials in this chapter come from Open Music Theory, with the exception of the tables of figured bass symbols, added by Elizabeth Pauly.