9 Chapter Nine: Writing Moves

Genres

An Exploration of Genre

In writing, you have a variety of choices at your disposal. At its core, writing is

about communication, but how you communication is more complicated. Luckily, you can have a lot of fun too, but you need to know that, as the writer, you have the power over how you talk about your ideas.

As you plan ways to talk about your topic, you might consider specific types of writing moves. What we are calling moves are sometimes called modes or genres. You might even get a writing assignment that asks you to use one particular writing move; for example, “Write a persuasive essay…” or “Compare and contrast these two concepts…”. The thing is, writing moves rarely exist by themselves. They are often used, quite powerfully, in conjunction with one another. When writing, you might have to do any (or several) of the following:

- Define

- Explain

- Compare/contrast

- Persuade

- Use rhetoric

- Analyze

- Narrate

- Show cause and effect

Which moves you use and when depends, as always, on the triangulation between your ideas, the purpose, and the audience. For now, let’s explore what these different writing moves look like.

Define

When you think about defining, you immediately think about dictionary definitions. Phrases like, “Freedom is defined by the Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary as…” are so common in writing, they’ve become clichés. It makes sense, though. If you’re going to be talking about a

Connotations and denotations

A denotation is a generally accepted definition of a word, like a dictionary or encyclopedia reference. Think about what a definition includes: meanings (usually multiple), parts of speech, pronunciation, original (etymology), and more. These are all important things. If your audience does not understand how to use or pronounce a word, they could miss important ideas in your writing. If you use a word or term your audience might not know, you need a clear definition. If you are writing about euthanasia, you might need to consult a medical source to get a clear definition or a law source to define the term. You might also need to define legal terms associated with the first term, like “physician-assisted suicide.” These terms and ideas might be essential to your paper, so you want to make sure the audience understands the meaning.

Definition/Denotation:

The National Cancer Institute defines euthanasia as “An easy or painless death, or the intentional ending of the life of a person suffering from an incurable or painful disease at his or her request. Also called mercy killing” (NCI).

According to Cornell Law, “Physician-assisted suicide is an end of life measure for a person suffering a painful, terminal illness. It is considered a form of active voluntary euthanasia , also described as a mercy killing or the “right to die” (Physician-Assisted).

A connotation refers to emotions and ideas you associate with certain words and terms. For example, in the examples about euthanasia and Physician-assisted suicide, you audience might have very strong emotions surrounding theses idea. Even the terms themselves have different feelings: euthanasia is very clinical while using the word “suicide” brings up more negative emotions (as does mercy killing). As you use words and terms in your writing, think about how they play on your audience’s feelings. This can be powerful, especially in an argument or persuasive move.

When defining, consider:

• Using a denotation when useful and not over general

• Different synonyms of the word

• Connotations of the word

• The context of the word or term and how you use it in your writing

Explain

Explaining is similar to defining. The difference? Consider the concept of a “Curfew,” as mentioned above. A definition of a curfew is a time that is set by an authority that assures people under the jurisdiction of the authority are within a certain boundary at that time. A simpler definition? A curfew is a time parents set for their kids to be home at night.

Explaining curfew, however, is far more involved.

Example of Explaining

• If your town has a curfew for its minors, you can explain the history behind it: perhaps there was a terrible incident that occurred that resulted in the creation of the curfew.

• You could explain curfew through a story that happened in your life around curfew and what happened when you “broke” it (came home late).

• You might explain different aspects of curfew. Sometimes it is just being home on time, but sometimes it is making sure the house is locked up and lights are turned off, too, or checking in with parents to let them know the kid has arrived home safely before heading off to bed.

You might see, now, how these writing moves might work with each other. You can define curfew but then go on to explain it further.

When explaining, consider:

• What the audience might already know about what it is you’re explaining and use that as a baseline for where you can start your own explanation.

• The variety of ways things can be explained, especially through real-life examples.

• Not explaining too much. This is called “pedantry”—you’re assuming the reader’s knowledge base is less than it actually is. Don’t talk down to your readers.

Compare/contrast

Comparing and contrasting can happen separately or together, and they can be done with two things that are similar or completely different. It’s a natural part of our thinking as humans. We often have an experience and compare it to a previous experience or think about how we were treated in one instance and contrast it with a similar experience.

Often, we compare similar services or products. Let’s say you want to go on a vacation. To make this happen, you need to get to your destination, and you need to figure out a place to stay. You might log in to a travel service to figure out how much it costs to fly. Already, you can probably imagine all the ways in which you can compare and contrast:

• Costs of flying out of one city versus another

• Difference prices among the airline carriers

• Cost of flying compared to the days and times of the flights

Of course, when looking for a place to stay, the same things start to happen. You’re looking at:

• Renting a house versus staying at a hotel

• Costs from one lodging to another

• Physical features of different hotels or vacation homes (appearance, rooms)

• Locations of lodgings from activities you are planning

• Amenities included in either a house or a hotel

What if you’re worried about the cost of flying? You’ve got it: you’re setting up another comparison to other modes of transportation like driving or taking a bus.

Because there is often so much to consider when comparing and contrasting, this writing move can often feel like it’s more than enough by itself for a piece of writing. But even when comparing and contrasting, other elements can come in. Look at the first sentences of the two body paragraphs in this example:

Example of Compare and Contrast Moves

Mow, Wow! The Best Way to Mow

I have to buy a lawnmower. I live in the suburbs, and one must have a lawnmower when one has a lawn. But which type of lawnmower? That is the question. A riding lawnmower or a push mower? My lawn is only one acre, but the grass grows quickly in the summer, and I want to make the right choice.

A riding lawnmower looks a bit like a small tractor with a mower attached to the front. You sit on top of it, driving it around the grass to cut it. This type of mower is easier on the back. You don’t have to sweat as much when you ride. A riding lawnmower is big, too, and gets the job done quicker, because the wide blade is cutting so much grass per second. A riding lawnmower can also be used by all members of the household—my elderly father can even cut the grass with a riding lawnmower if he wishes to. But on the other hand, a riding lawnmower is expensive. It is also bigger, so you have to have more space in the garage to store it. It is also an attraction to children, and they could get hurt on it.

A push mower is like a riding mower without the tractor part to sit on. Instead, there is a handle attached to the mowing part that you have to push around your yard. As you might guess, it helps you get much more exercise when you use it because you are using your arm and leg muscles a great deal as you push, especially through the taller grass. A push mower can also get into littler areas, so you don’t have to go over the lawn with a weed-whipper when you’re done mowing to get all the spaces under the deck and around trees. A push mower is also small and easily stored. A push mower creates less pollution because the engine is so small. But a push mower is also slower, so will the grass get mowed as often if I get a push mower? And with a push mower, it takes longer to do the entire lawn as the area the blade is cutting is not very large.

I think I’m going to go with a push mower. I like the idea of getting more exercise whenever I cut the lawn. I like the cheap price. I want to help the environment. And, let’s face it, I don’t want the neighbors in my uppity suburb to think I’m lazy.

As you can see, those topic sentences explain what riding and push mowers are. Even when primarily comparing and contrasting, you need the help of other writing moves.

When comparing and contrasting, consider:

• Limiting the elements you are going to be comparing/contrasting. Too much can be confusing.

• Assuring that you are comparing the same things about each topic. For example, if you’re comparing one restaurant to another, talk about the food, the service, and the prices for each. Don’t talk about the food, the decorations, and the cleanliness for one and then talk about the food, the service, and the prices for the other.

• Sometimes two completely different things get compared, like comparing eating ice cream to a blind date. This can be fun, but make sure the reader understands why you’re making that comparison.

Special Consideration: Organization for Compare and Contrast

Organization is critical in compare and contrast. There are a lot of points being made within these types of papers, and a reader can get lost if those points aren’t flowing well. For compare and contrast, you can choose “Whole to whole” or “Point by point” organizational structures. Let’s consider what those might look like by way of example.

Let’s say you’re comparing four-wheel drive and all-wheel drive vehicles. The audience is parents with young kids who have just moved to Minnesota from a southern state. You need to come up with points of comparison that are useful for that audience, such as:

• Cost of the vehicle

• Reliability over time

• Gas mileage

• Traction on the road

Based on this audience and their foremost desire for safety on the treacherous winter roads, you might want to use a general order of importance to get your points of comparison in order, going from the most important point to the lesser points:

• Traction on the road

• Reliability over time

• Cost of the vehicle

• Gas mileage

Once you’ve decided on the order of your points of comparison, you have two choices when it comes time to organize the whole essay: whole to whole or point by point.

With whole to whole, you talk about Topic One and then Topic Two.

Example of Whole to Whole Outline for Compare and Contrast Writing

Four Wheel Drive Vehicle

• Traction on the road

• Reliability over time

• Cost of the vehicle

• Gas mileage

All-Wheel Drive Vehicle

• Traction on the road

• Reliability over time

• Cost of the vehicle

• Gas mileage

Note: The order of the points of comparison is the same for each type of vehicle.

Example of Point by Point Outline for Compare and Contrast Writing

Traction on the road

• Four-wheel drive

• All-wheel drive

Reliability over time

• Four-wheel drive

• All-wheel Drive

Cost of the vehicle

• Four-wheel drive

• All-wheel drive

Gas mileage

• Four-wheel drive

• All-wheel drive

Note: For each point of comparison, you would talk about four-wheel drive vehicles first and then move to the all-wheel drive vehicles.

The point here is to assure that you’ve chosen one structure, and you’re adhering to the same order for all the points. It might seem tricky, but an outline such as those above will help.

Show cause and effect

Cause and effect are natural parts of our lives, so much so that you’ve probably heard one of these sayings:

• You get what you give.

• You reap what you sow.

• History repeats itself.

• What goes around comes around.

These clichés speak to cause and effect: things that happen, or things people do, have impacts on other things or people.

• The assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand caused World War I.

• The United States entered World War II after the bombing of Pearl Harbor.

• Not wearing your retainer after braces will cause your teeth to shift in unpredictable ways.

• A kid eating too much candy after Halloween trick-or-treating will make him sick.

Obviously, several of the above examples have much more dire consequences than others, but the point is the same. Sometimes in writing, we need to show how one thing impacts others, or how several actions might result in something happening. This is not always a simple equation of one thing happening causing another thing to happen, such as bowling a ball down a lane will (hopefully) knock down pins.

Sometimes, it’s more complicated:

- Eating poorly, staying up too late, registering for too many classes, and not socializing can have the effect of stress.

- Registering for too many classes can cause stress, neglect of friendships, and poor sleeping habits.

- Sometimes, several things cause several effects:

- Cutting down trees in my backyard, adding grass, and putting up a playset for my kids can cause my kids to be happier, more sunshine to come into the yard, and a decreased habitat for small wildlife critters.

What you’re doing as a writer when you use cause and effect is to show that you understand the complexity of a topic, and you think it’s important that the audience understands that complexity.

When using cause and effect, consider:

- The value of using it. It can be confusing, so make sure you understand as much as possible about what you’re showing.

- If you don’t fully understand all possible causes and/or effects, you can say that in the writing. It’s better to tell the reader that you might not be covering all possibilities than to pretend that you are.

- Make sure that the causes and effects you’re showing are actually related.

Examples of Mistakes people make when trying to show cause and effect

- Assuming that because some event happened first, that it had to have caused whatever came after, called post hoc, ergo propter hoc. For example, one time I went to a restaurant and had a hot beef sandwich and later that night, I got very sick. I might assume I got food poisoning from the restaurant when, in fact, I had the flu.

- Assuming that because of one example, this must always be true, called a hasty generalization. For example, if you read one book you didn’t like by Tom Clancey, that must mean you’ll hate all of his books (and he has MANY).

- Assuming that if one step is taken, there will be a series of ever-more disastrous consequences (called slippery slope). For example, if we lower the drinking age to 18, then all young people are going to start drinking, upping the number of alcoholics and drastically increasing the number of deaths due to drunk driving and causing a massive healthcare and incarceration crisis in the country.

Analyze

Analysis is fun. It involves picking something apart to understand how it works. This happens all the time after sporting events, called “the post-game analysis”. American Football fans around the world wanted to know how the Philadelphia Eagles managed to win so decisively against the Kansas City Chiefs in the February 2025 Super Bowl. Closer to home, maybe you wanted to know what made for such a magical basketball team your senior year in high school—so magical that you won the state championship.

When you analyze something, you’re really digging into it, learning as much as you can about it. Some might call this “geeking out.” When you’re online, sometimes something catches your attention, and you get distracted. You MUST learn about how Upton Sinclair did his immersive exploration into the slaughterhouses of Chicago before he wrote The Jungle, or you need to know how the producers of the long-running and much-beloved quiz show Jeopardy! went about finding a new host after Alex Trebek died. This is what we call “going down the rabbit hole,” and when using analysis in writing, you’re inviting the reader along with you.

You might wonder what the difference is between analysis and explanation, and for that matter, defining. You can think of them in terms of degrees. Defining is fairly basic. Explaining is more in depth. Analyzing is really digging in.

When using analysis, consider:

• Most importantly, the audience’s tolerance for the analysis. If it gets to be too much, the audience might get confused or, worse, completely stop reading.

• Set up the analysis ahead of time by indicating why it’s important. A solid thesis statement can help. For example: “To truly get your hard-earned money’s worth, it is critical to understand the inner workings of a Patak Phillipe watch.”

• Assuring you know what you’re talking about. This means that you might need to consider using outside research to support your analysis (make sure you properly cite your sources!).

Narrate

Writing a narrative is one of the best ways to convey your ideas as the writer. It comes as closest to fictional storytelling as you can get when writing an essay, and when done well, it is incredibly compelling for the reader.

Example of Narration Move

You live in a house with three roommates. When you get home from work one night about 9:30, the lights inside are blazing, which is normal, right? Except for one thing: one of your roommates is at work still, another roommate should have left to go home for the weekend, and the third is a gamer whose room is in the basement, and when he’s home, you’d never know it upstairs.

So, this situation is weird, but you’re also really tired from work. You’ve been on your feet all day and just want to shower up and stream something mindless before bed. As you walk up the driveway from your spot on the street, you have a sinking feeling in your stomach that something isn’t right. It seems like ALL the lights are on, but you can’t see anyone inside.

When you get to the side door, you hesitate a moment. Maybe you shouldn’t go in. But what else are you going to do? You turn the knob…

…and when you walk in, the first thing you hear is laughing. The kind of laughing that’s been going on so long and for so hard that there is some gasping and possible crying happening. A split second later, you realize that it’s as though a glitter bomb has gone off. Glitter is all over. On the floors, the counters, in the light fixtures, on the furniture, in the kitchen sink, in the cat bowl…everywhere. You go into the living room, where your roommates are still howling with laughter on the floor, and there, amongst them, is a glitter cannon.

“So, anything interesting happen while I was at work?” you ask, and this sets your roommates off again.

THIS is an example of narration. It’s longer than you might usually see in an essay, but it demonstrates the kind of work that happens with narration: it tells a story, personalizing on the topic you’re working with to help your audience experience it in a more direct way. Often, narrative work happens as an introduction, but it can happen in the middle of a piece when it feels like some life needs to be brought into a piece.

For example, if you’re analyzing the negative impacts of social media on teen girls, and you were, in fact, once a young girl being negatively impacted by social media, you could tell a story of what that looked like. You could also tell a fictional story about that happening, but the key if you’re going to make up a story is that it needs to be plausible and realistic. Readers will see right through you if you make up something silly or unnecessary.

Another aspect of narration is description. When you’re describing an object in writing, you’re giving physical characteristics, but you can also describe spaces, processes, or even feelings. When talking about the history of the building of the Space Needle in Seattle, you could describe what it looks like, but also how it feels to go up to the top of it and all you can see from that vantage point. You can also describe the process of how it was built.

When using Narration, consider:

• Use it when you want the reader to be able to experience what it is you’re talking about.

• Keep the story short. If it gets too long, the reader will lose the thread on what point you’re trying to make by including it.

• Assure that if you’re making up a fictional story, that it’s realistic and representative of the point you’re trying to make.

Persuade

So far, we’ve looked at various writing moves you can make in your projects. This next writing move, persuasion, is one that we often view as completely different than the other moves. At some point in your schooling, you might have heard teachers talk about informative versus persuasive writing, as though they are always separate.

The truth is, though, that when you’re trying to convince your audience (persuade or argue), there is always some informing happening, too. On the other hand, in a piece of writing where you’re feeling like you’re simply informing the audience, there can be some subtle persuasion happening there, too. It might be as simple as asking for the audience’s attention by reading your piece. That’s a form of persuasion, getting the reader to both start AND keep reading.

It’s important to know, though, that when your first instinct is (or the assignment calls for you) to persuade, there are some specific elements of persuasion that are worth knowing.

Elements of Persuasion

First, when your intention is to persuade, your thesis statement is critical. This is where you state your argument clearly and succinctly:

Watering flowers by hand rather than with a hose brings gardeners closer to nature.

The effects of global warming can only be mitigated through the outlawing of gas-powered vehicles.

Football players should take dance classes because of the strength training, dexterity, and mind-body connection it uniquely trains.

Then, you come up with the variety of points you want to make to support your argument. You also consider counterarguments, which are the reasons why your audience would disagree with you…and your audience for a persuasive essay is always a group who disagrees with you or a group who must be moved to change.

Introductions for persuasive essays can help illustrate the problem resulting from the issue (a “before” snapshot), and conclusions can show how much better things are when the change has been made (an “after” snapshot).

A big question that comes up with persuasion is how, exactly, it’s done. Luckily, one answer has been around for thousands of years, and it comes from the ancient Greeks.

Using Rhetoric

Rhetoric means “the art of argument”. It is carefully thinking out and planning how you are going to persuade someone else. Yes, this means thinking about audience, your main point, and the evidence that you’ll use to support your point. But it is in the evidence part of this where rhetoric comes in.

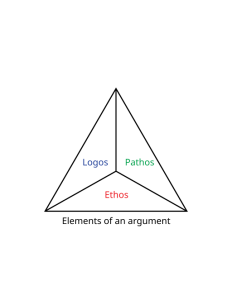

The most commonly discussed form of rhetoric is called Classical, or Aristotelean, rhetoric. It was described by the Greek philosopher Aristotle in his book Rhetoric and Poetics. It is a book of philosophy, so there are a great many concepts described within it, but at its core, there are three main aspects of rhetoric that are used in college writing classes today: Ethos, Pathos, and Logos. Ethics, Emotion, and Logic are three powerful ways we can persuade our audience, and you probably do this anytime you’re trying to persuade someone, but you’re not thinking consciously about it. Aristotle (and your writing teacher) will suggest that you do.

in college writing classes today: Ethos, Pathos, and Logos. Ethics, Emotion, and Logic are three powerful ways we can persuade our audience, and you probably do this anytime you’re trying to persuade someone, but you’re not thinking consciously about it. Aristotle (and your writing teacher) will suggest that you do.

Let’s take a look at them one at a time.

Ethos

Ethos in the Greek translates to “Ethics”. Aristotle spends a lot of time in his book describing ethics in the most philosophical of ways, but for our purposes, we are going to consider ethics in a narrower sense. Specifically, by “ethics,” we mean “credibility”.

Think about it: if you’re going to show your audience you know what you’re talking about, how could you do that?

You might immediately think about adding research, and you’d be right. Of course, doing a simple internet search and adding in whatever comes first in that search is not the ideal situation. Why? First, the information might not be solid, and second, your audience can also do an internet search. As the writer, you need to do MORE than the reader.

When you have found solid sources, though, with useful and interesting information and written by people who clearly have expertise in the topic, you are effectively using ethos.

But wait! There is another way you can use ethos in your writing, and that is through your own expertise. We can often discredit our lived experiences as being not “good enough” to support a formal argument. It’s worth considering, though, as significant experience can hold a lot of weight for a reader. It shows that you really understand what you’re talking about.

Of course, this can go poorly. If you’re writing about what it feels like to have a baby and you’re a person who has not had a baby, that will not have as much weight as a person who has had the physical experience of having a baby. It’s kind of like when you’re feeling sad about your dear grandmother passing away and a friend says, “I know EXACTLY how you feel. I was so sad when my goldfish died.” Your friend’s attempts at ethos have failed.

In general, though, if you know a great deal about your topic, it’s worth considering how you can use that expertise within your project.

Pathos

Pathos in the Greek translates to “pathetic,” but in a different sense of the word than it is most commonly used today: it means “emotion,” and there a few things to understand about using this in your writing.

First, the goal is not to be emotional in your OWN writing. Of course, the reader will certainly understand if you’re ranting and raving about some injustice in the world, and they might feel the same way, but just as often, you might come across as unstable or unreliable. You definitely don’t want that.

So, using pathos in writing is about trying to get the reader to feel something. This can be done by using humor, or it could be including a sad story, or, yes, it could be spelling out an injustice that occurred. The goal is for the reader to feel the feeling you’re trying to invoke. Often, this is done through storytelling, so look at the section above on Narration for more on that.

The thing to keep in mind, though, is that it doesn’t always work. Think about how many times someone has tried to make a joke that’s just not funny. People find different things funny, and when a joke falls flat, well, it can be a little embarrassing. As the writer using pathos, know that you’re taking a calculated risk. Many writers do, in fact, take that risk even when they know the stakes are high precisely because when pathos works, it is hugely powerful—it can be even more powerful than ethos and pathos combined.

Just be careful.

This is an instance where getting other people to read your work to tell you if the pathos is working would be an excellent idea. You might think you’re telling a story that will pull on the reader’s heartstrings, but it’s better to ask someone (or several someones) to assure that is, in fact, happening.

Logos

Logos from the Greek translates to “Logic.” In the United States, we put a lot of value on making logical arguments; we like when things make sense and are “provable.” As a result, most arguments should include a healthy portion of logic. There are two ways of doing this.

First, you can include logos by incorporating common sense. On a sunny day, that means that the sky is blue. That’s common sense. Or, saying that college students who take too many classes will likely get stressed is common sense. Noting that the internet has completely changed how we humans interact with each other is common sense.

Be careful, though. What you might assume is common sense may not be to others. For example, Bill might say that it’s common sense that the Minnesota Vikings are not a good American football franchise because they’ve never won a Super Bowl. His friend Andre, however, could dismiss Bill immediately because he doesn’t think a team’s overarching abilities should be judged based on that one standard. Of course, Bill could go on to defend his claim, but he will need to bring up much more evidence than he might have previously thought to convince Andre.

The second way you can include logos is by including factual information. Numbers and statistics are commonly accepted forms of logos. For example, stating that 97 percent of college students who take more than 20 credits in a single semester are likely to drop out of school altogether would be an element of logos.

If you’re questioning this statistic, good for you! I made it up, and this is where the use of logos can be weak: when you don’t also include ethos, or credible sources, to help back your facts up. This is where this type of logos can fall apart: when you state something as though it is fact but the reader doesn’t believe it is, indeed, an actual fact. As the writer, it’s up to you to assure the audience believes you. Include solid sources with citations to help support your use of logos.

Let’s look at how ethos, pathos, and logos work a real-life argument based on what you know about your audience.

You are trying to persuade your mother to let you go on a study abroad trip for a semester. You need to come up with arguments and evidence that are made specifically with your mom in mind because you know her: you know what kinds of argument work on her and which don’t: “But mom, all my friends are going!” won’t cut it. You know which commercials make her tear up (the ones with sick babies and kids graduating from college). You know she doesn’t trust online news sources. By considering these factors, you can give the best argument and persuade her to let you go to Paris!

Putting It All Together: An Example in Action

Here’s how we could apply ethos, pathos, and logos to this example:

Ethos is a way of convincing your audience through credibility. You display to your mother that you have done well in college, you have been on the honor roll, have been responsible. You also have a letter from your history professor who recommended you for the program.

Pathos is a way of convincing your audience by appealing to emotions. You remind your mother of how she is always telling you about that trip to Germany she took when she was in high school—how it opened up her eyes to the wonders of the world—and that was only two weeks. Imagine what six months in France would do!

Logos is a way of convincing your audience by providing factual support and data. You display to your mother that researchers independent of international study abroad programs found that college students who study abroad have higher graduation and employment rates than students who do not study abroad.

More Rhetorical Power: Ethos, Pathos, and Logos Combined

This brings up another critical point: use ethos, pathos, and logos in combination with each other to make even stronger arguments. As noted above, the most obvious example is ethos and logos, where you use a statistic you found in a credible source and then cite the source, showing the reader where the information came from.

You can also use logos and pathos: discussing the heartbreak a parent feels when a child is gravely ill is both common sense (of course a parent would feel terrible) and could make the reader feel a bit of that sadness.

Pathos and ethos also work well together. If you tell a sad story and it’s from your life, that’s powerful. If you tell a sad story that another well-known person has experienced, that, too, is powerful.

Example of Combining Ethos, Pathos, and Logos

We all know that smoking cigarettes is at the very least unhealthy, and at worst, deadly; this common knowledge would fall under the category of logos. Despite this knowledge, many people still smoke. Governments all over the world have attempted to dissuade their populations from smoking through a variety of means, the most common of which are the warnings on cigarette packs.

In the United States, we have long had warnings printed on cigarette packs telling smokers what negative health effects smoking has on our bodies. This is another example of logos. Often, you can also see that the warning comes from the Surgeon General, who is the “top doctor” in the country. This would be an example of ethos, or expertise in combination with that logos.

Some countries take it even further: there will be actual pictures of, for example, diseased lungs that resulted from smoking printed on the cigarette packs. In these instances, it’s believed that it’s not enough to simply say that smoking causes lung cancer; consumers must be shown the cancer. A variety of feelings, all of which would be negative, would result from seeing such graphic depictions of the perils of smoking. This would be an example of pathos.

Another Part of Persuasion: The Counterargument

When you’re trying to persuade an audience, something you might want to ignore are the very good reasons why the audience disagrees with you or the excellent points that speak against your argument. The truth is, most arguments are not cut-and-dried, right and wrong. Some are, of course, but for the majority, there are good reasons why things are the way they are and why people think and do what they do.

If you’re doing a good job arguing, you will speak to those points.

You might have learned that you bring up the other side’s arguments with the sole purpose of squashing them like a fly under a fly swatter. That shouldn’t be your intention, however, and the reason is because it rarely works. When is the last time someone told you what you thought was ridiculously silly and you said, “Oh, you’re right. Thank you very much for telling me that. Now I know better and am no longer a fool.” It doesn’t happen.

Instead, you should really consider where the other side is coming from. Get curious. Why do they think the way they do? What happened historically that led to this policy? Are there other, seemingly unconnected, reasons why things are the way they are? Dig in and figure it out, and then write about it. You might end up limiting your claim, which means that the stance you’re taking isn’t quite as strong as it originally was. “Limiting your claim” means that you shrink it down in some way. Instead of saying “This needs to end altogether NOW,” you might say “This part of the issue needs to end now,” or “This needs to end now, for a certain period of time, to see the effects of the changes.” Perhaps there are instances where whatever is happening that you want to end can continue.

You might think that this would weaken your argument, and in a way, you’d be right: if you’re taking a hardline stance on something, considering the counterargument and then changing your argument because of it is making it “weaker”. Think of it this way, though: it can be so difficult to make changes. Is it better to have a slightly smaller change actually happen, or better to really go for it and have it all fail? The choice is yours as a writer, but you’re far more likely to make headway on your purpose, which is to convince the audience, if you actually consider what it is they think/do/believe in a sincere and respectful way.

Works Cited

“NCI Dictionary of Cancer Terms.” Comprehensive Cancer Information -National Cancer Institute, www.cancer.gov/publications/dictionaries/cancerterms/def/euthanasia. Accessed 27 May 2025.

“Physician-Assisted Suicide.” Legal Information Institute, Cornell Law School, www.law.cornell.edu/wex/physician-assisted_suicide. Accessed 12 Mar. 2025.

Media Attributions

- People dancing with books © Designed by pikisuperstar / Freepik

- Three_elements_of_an_argument.svg © Nanodudek, CC BY-SA 3.0 , via Wikimedia Commons is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

A specific type or category of writing—such as essays, research papers, reports, or literature reviews—each with its own conventions, structure, and purpose tailored to academic communication.

The literal or primary meaning of a word, in contrast to the feelings or ideas that the word suggests.

The implied or emotional meaning associated with a word, beyond its literal definition, which can influence tone and reader interpretation.

To examine and break down information, ideas, or texts into parts in order to understand their meaning, structure, and significance, and to explain how they contribute to a larger argument or purpose.

A spoken or written account of connected events; a story.

A rhetorical strategy that appeals to the credibility or character of the speaker or writer.

A rhetorical strategy that appeals to the audience's emotions.

A rhetorical strategy that uses logic and reason to persuade an audience.