14 Chapter Fourteen: Using the Research Process

Now you know about the basic writing process and how to write based on what’s in your head. Now, it’s time to learn more about research, which kicks your writing up to a new level. You might consider it strange to be thinking about research so late in the process. We’ve almost been trained to “Google it” or, more recently, to ask ChatGPT if we have any questions or if we’re not sure what we think about something.

We would like to encourage you to stop that practice, at least at first.

It can be uncomfortable to not know what, exactly, you want to say or how you want to say it. It’s important, though, to sit in that discomfort, to allow yourself the space to think. We promise it’s worth it to practice that intentional wondering, to allow yourself to get into the space of curiosity about your topic.

Once you have your own ideas down, you might still be curious. You want to know more, and your audience might also want to know more than what’s in your head. You want more facts, more stories, more expertise (logos, pathos, ethos).

This is where research comes in.

Researching a writing assignment

You’ve got a writing assignment. Perhaps its parameters are specific, based on something you might be studying in class:

Write a 5-6 page essay describing the purposes of Benjamin Franklin’s various trips to Europe pre-American Revolution and the effects on the Revolution itself.

Sometimes the parameters are specific to you:

Write about a misconception others have about you and why they’re wrong.

Or, at work, your supervisor might give you a daunting task:

Write a report explaining how the IT department met its performance goals in the past year

Other times, though, the assignment is broader:

Write an argumentative essay that effectively utilizes ethos, pathos, and logos along with two scholarly sources to make three to four salient points in support of your side of the argument along with at least one counterargument that is then refuted in your text.

Whew! Like we said earlier, for many of us, the first instinct is to fire up our web browser of choice and do a quick internet search or ask Generative AI to figure out what to write about. At that point, however, you’ve just given up control over your essay. You’re letting the ideas of others take over your planning, and it might (even unconsciously) color your own thoughts on the topic.

Let’s get into this a bit more.

Does it make your life easier to do this preliminary searching? Sure. The problem, however, is that if you want to improve your ability to think and then write about those thoughts, then the search you do before you do your own thinking hijacks the essay. Your piece then becomes a collection of others’ ideas, when the point is for you to look at your own ideas and then make them more complex by bringing in those outside sources.

Ultimately, when you’re given an assignment and you’re not sure where to start, follow the advice in Chapter Four of this book for getting out some of your own ideas. Don’t be afraid of them.

Once you’ve landed on a topic, do some freewriting to get as many of your own ideas as possible, even if you’re not sure that you’ll use all of them in the essay. Look at where you might have some holes in what you know. These holes can now be filled with research: fire up those computers, because it’s time to start digging.

The Ultimate Rule for Research

Don’t let the research drive your ideas.

YOU drive your ideas.

All the Sources

The whole point of research is to find the good stuff. You want sources that are solid, presenting information that is as unquestionable as possible. What are these sources?

Source Quality

Excellent sources. The best sources to use are called primary sources. These are the actual text of a work, such as an eyewitness report, the word-for-word law, the text of the most important book/s in the field, or, (sometimes, but rarely) the text of the important article in the most important journal/s in the field. An excellent source is any text that important experts and stakeholders turn to when they have to make a decision in real life about any given topic. An example of this is the actual text of the U.S.’s Declaration of Independence.

Good sources. These are articles (online and in print) and books written by academics about the topic area you chose. Also, dictionaries, encyclopedias, and textbooks. An example of a good source would be an article talking about the historical context of the Declaration of Independence, or a well-known political science scholar’s analysis of it.

Okay sources. Magazine and newspaper articles, or articles authored for use on the internet only. These are often not written by experts and increasingly they are written by AI (like a Google AI summary of the Declaration of Independence).

Suspect sources. These are sources that include information that is so broad, it’s barely informative, or include information that is out of line of what common understanding is of the topic. Avoid these. There is lots of incorrect factual information out there.

Choosing Types of Sources for the Topic: Examples

If I am writing about Shakespeare, an excellent source is Shakespeare himself. A good source is a book written recently by a scholar about Shakespeare.

If I am writing about the criminal mind, excellent sources are articles and books about the criminal mind, as well as important court cases and texts of law and psychology that govern how we deal with and think about the criminal mind.

If I am writing about how my summer vacation went, the first most excellent source would be myself. The second would be my mom, or other people who know the most about what I did. If I need research or facts, I might look at travel journals or tourism websites on the places I visited.

If I am writing to argue for or against a local bar ordinance in my hometown, excellent sources would be the text of the ordinance itself and a statement given by the chief of police. Good sources would be articles in academic journals about local bar ordinances as well as any articles in local newspapers that cover the topic of the ordinance carefully.

If I am writing about American policy on the war in Afghanistan, an excellent source would be a government document that governs the policy of the war today. Another excellent source would be a widely-read book or article about the war written by an expert in the field. A good source would be an academic journal article about the war written by an academic.

In general, original texts and those texts that people read and routinely refer to are the best texts.

Finding Sources

Where do you find information on a topic? Google it, obviously! Yes, in the early college courses you’re taking, the internet likely has all the information you’ll need to address your writing topics. This might also be true in the working world. There are many other resources, however, worth your consideration. Varying your source type will make your research stronger and show that you’re a thoughtful writer.

Also, remember: you need to consider your audience and purpose before you start your research to determine what that group might need in terms of outside sources.

Basic search engines

The information you need is right at your fingertips.

This is a cliché for a reason: it’s true! Going online is the easiest way to research your topic. Most of us use Google, but Bing, Yahoo, among others, are also popular, and we can easily pull these up on desktops or laptops or as apps on our smartphones. Yes, it’s easy to find information using a search, especially when the search engine offers search terms for us as we’re typing in what we’d like to find.

There are a few things to watch out for, though.

First, many search engines will give you search results based on previous searches. That’s right: beware of the algorithm. This means that when you Google “political correctness,” the search results you get might be different than your buddy Malcolm’s, which might also be different than Ariana’s. They will also start with “sponsored” sources, which are often selling something or organizations that pay to come first. Now, AI summaries also come up first, but these are based on huge amounts of data and are not always accurate.

Also, you want to be clear about your search terms. Instead of searching for “Lyme disease,” which will likely give you a basic definition along with over 60,000 results in less than a second (that’s a LOT of information!), search for “Lyme disease Minnesota” or “Lyme disease alternative treatment” for more specific information and data. You can also type in questions, like “Can Lyme disease be cured?”

Remember, though, that just because a source looks good, that doesn’t mean it is good. And by “good,” we mean appropriately scholarly or professional for your topic and purpose.

Academic databases

As a student in college, you’re lucky because you have access to an amazing wealth of solid research sources via free access to academic databases. What’s a database? It’s a search engine for sources that are usually only found in print: academic journals, magazines, and newspapers.

You know what magazines and newspapers are, but you might not have a lot of experience with academic journals. Journals, such as the Journal of the American Medical Association and The Lancet, are where experts in a field publish their studies. These essays are peer reviewed, meaning that other experts read the studies and agree that the findings therein are correct. What this means for YOU is that an academic journal is often a great source for your essay.

The other sources found in databases, magazines and newspapers, are also good sources. The best thing about looking for, say, a newspaper article on a database rather than online is that in a database, the access is free and goes back for years and years. When you look online at a newspaper, sometimes you can only search so far in the past or can only look at a few articles before you have to pay for access. No, thank you! Use the databases instead.

Tips for Database Searches

- Use search terms like an internet search engine. Don’t ask questions, however. Remove unnecessary words, like “the” or “in”. For example, you might Google “What are the main symptoms of Lyme disease?”, but in an academic database, you would search “symptoms Lyme disease.”

• Use an “advanced search,” you could search “Lyme disease” AND “symptoms” AND “Minnesota.” You can often limit the results based on published dates, such as looking for articles that came out in 2024 and 2025. You can limit your results by “Full text,” meaning that all the search results will be the full articles. Sometimes you only get an abstract, which is a summary of the article, and if you want the whole thing, you need to do an interlibrary loan, something your librarian can help you with.

• Speaking of librarians, use them! They are specially trained to be experts on research strategies and love to help students who are proactive about finding solid sources. Conduct your research in the library where it’s quiet, the resources are free, and live human help is right there for you.

The other great thing about an academic database? It will create a full citation for you, so you don’t have to worry about starting from scratch to create it yourself. Of course, it’s your responsibility to double-check the correctness of the citation generated by the database, but it’s likely to be right.

Print books, magazines, and journals

While you’re in the library, why not search through the available print materials? You can’t get much more scholarly than a good old-fashioned published book. Plus, some topics that don’t change a great deal (such as the geology of Minnesota or anatomy) lend themselves better to book research.

Print books can be wonderful. Though it might seem intimidating to think about looking at an entire book, worry not: use the Table of Contents in the front of the book or the Index in the back as a way to ferret out the sections in the book that will be useful for your research.

What about magazines and journal articles? Though you can find more magazine and journal articles in an academic database than you’re likely to find in print in your library, sometimes browsing through those print sources can spark other ideas; you might run across information in a magazine you didn’t previously think about, or sometimes your eyes get tired of staring at a computer and you need to rest them by looking at a printed page. Whatever the reason, it’s worth looking at the printed resources in your library.

Interviews

Probably one of the most often overlooked resources when doing research is to use other people. Why not talk to a person or interview them via email? Specifically, why not talk to an expert on the topic you’re researching? Who better to learn about Lyme disease from than a doctor or someone who has it? These experts can provide solid information that can also put a personal touch on the topic.

There are a few things to be careful of when considering a person to interview, though:

• The person should actually be an expert. Your cousin might know a friend who had a brother whose friend has Lyme disease. The cousin is NOT an expert, and neither is the brother; only the person who has it is the expert. Also, don’t confuse usage with expertise: a friend might use Snapchat constantly, but that doesn’t mean she’s an expert (except, perhaps, being an expert on addiction to social media).

• Ask for an interview with plenty of lead time and explain what you’re doing. People are busy. How would you like it if a random person contacted you with a bunch of questions they needed answers to tomorrow? You’d ignore that person. Instead, make it easy for the expert to help you out:

- Say who you are, what you’re doing, and how you got the expert’s contact information (it’s especially good when you’ve been referred to the person by a common acquaintance—that’s networking at its finest).

- Explain when you need the information (at least a week ahead of time).

- If you’d like to meet in person, give as much lead time as possible and as many time options as possible.

- Include your list of questions. You shouldn’t overwhelm the expert: give them five questions or so.

- Give the expert several ways of getting ahold of you; a return email is likely, but offer a phone number for the person to call or text if that’s more comfortable.

- Always thank the expert for his or her time. Remember, time is a valuable resource!

- If it’s an email conversation, cite as an email source. If conducting the interview in person, it’s cited as a personal interview.

Creating Interview Questions

There are also several things to consider when you’re creating a list of interview questions:

• What’s the purpose of your research? Focus in on a specific aspect of the topic that needs an expert’s ideas. DON’T rely on an expert for everything you need in your research.

• Don’t overwhelm your expert with a huge list of questions. Three to five questions is a “polite” number: this would get enough information but wouldn’t be an overwhelming number for your expert to answer.

Tips for Writing Interview Questions

When writing questions, phrase them so they are open-ended and neutral:

Closed-ended questions get a limited amount of information.

For example: Does this hospital have a policy on hand washing?

Open-ended questions allow for expansion.

For example: What are the hospital policies on hand washing, and how have

employees responded to those policies?

AVOID leading questions, which suggest an answer and can demonstrate an incorrect assumption that can make your interview subject feel negatively about you and the interview.

For example: Some employees here have been angry about the hand washing

policies, right?

Neutral questions are best; they’re just looking for information. The open-ended example questions above are neutral.

When asking questions, make sure they’re organized in the same order you’re planning on using the information in your essay. That makes your life much easier when you’re going to use it.

For example, if you’re talking with someone who has dealt with chronic Lyme disease, you might put your questions in chronological order:

-

- When did you first notice symptoms that made you go to the doctor?

- When did you receive your diagnosis? Was it difficult to get that diagnosis?

- What was your treatment plan?

- How are you still feeling the effects of your Lyme disease?

Use this interview information just like other sources: by quoting, paraphrasing or summarizing, and be sure to cite the information, too. In MLA, you cite an interview of John Lennon as:

Lennon, John. Personal Interview. 1 Jan. 1977.

In APA, there is no full citation in the References section; instead, you cite an interview parenthetically in the text next to the information from the interview:

(J. Lennon, personal communication, January 1, 1977).

Videos, podcasts, and other audio sources

As you’re conducting your research, consider utilizing non-print sources such as videos or radio programs. TED Talks, YouTube lecture series, National Public Radio, and specialized podcasts can be excellent sources of information and can help break up all the reading you’re doing. Just as you’d do when searching online, though, make sure the sources you’re using are appropriately useful and academic.

Just as anyone can start a blog and spout off their opinions on any subject under the sun, anyone can make a YouTube video and do the same.

Pictures

Sometimes a judicious insertion of a picture can help break up a text, orient the reader, or give a visual cue. Graphic artists are often employed by firms to do the visuals of a text after the writers have written the text. For most college writing courses, visuals are not required, as creating visual art is usually thought of as a separate skill. But you should be aware of the possibility for needing visuals. For example, in much science writing, graphs and charts are very important parts of the text. In a history class, you might need to include maps in your work.

Beware of bias.

The Website Litmus Test: How to tell if the website you’re looking at is credible or not

There’s a huge amount of information out there on the web, so it can be difficult to tell whether a website is credible or if it’s biased or just plain wrong.

Here are some things to look for when surfing for credible material on the internet:

1. The website has an author.

A website doesn’t have to have an author to be credible, but it helps.

2. The website author has a biography of his/her credentials.

3. The website comes from a source that’s reputable (e.g. a well-known college or university or an unbiased news organization)

4. The website looks boring.

Silly fonts, colors, pictures, advertisements, etc., can show a lack of professionalism.

5. The information on the website makes sense.

If you find a website with information that shocks you on your topic, beware. It could very well be biased.

6. It’s grammatically perfect.

A website that has a bunch of misspellings and run-on sentences is not to be trusted (keep in mind that effect on the reader when it comes to your writing, too!!).

7. The website has links to other reputable sources.

8. The information in the website is unbiased.

Obviously neutral information is good information to have. It’s not bad to use information from personal blog postings or other biased sources, but you must acknowledge that information as biased and not as fact—otherwise it will reflect poorly on you as a writer.

9. Watch out for the .com endings.

.edu, .gov, and .org endings can provide more credible information.

And finally one big DON’T:

Don’t rely on Wikipedia.

This editable-by-anyone encyclopedia is helpful for very basic information, but you’ve probably chosen a topic about which you should already know basic info. So it’s not helpful.

What is helpful: look at the end of the article for a list of sources—those can be useful for future research.

Keep in mind that none of the items listed above are deal-breakers (and it’s not even an exhaustive list!). When you start to see several of these red flags, though, and you’re starting to get the feeling in your gut that this source might not be good, move on. There are many, many, many more sources in the online sea. Other ways to evaluate sources include the CRAAP test and SIFT method.

Also, know that it is not a huge deal to use a biased source in your work, but you must acknowledge it as such in the writing or risk being dismissed by your readers. Again, audience is key.

Reading sources

One of the most daunting tasks of research is not finding the sources themselves but actually reading them. Even if you’re a person who loves reading, doing so for pleasure is not the same fact-finding mission that the research mindset requires. When you’re reading for research, you’re a detective, looking for clues in the world that will support your pre-set idea about a topic. When you think about it in those terms, reading requires a different set of skills. Sure, it might be different than reading a novel, but it can be easily practiced and will not require you to read carefully from beginning to end. You can get the information you need without making it too difficult on yourself.

Critical reading of sources

So, let’s say you’re looking at book you found that looks super useful to your research. How do you wade through it, knowing you’ll never have time to read the whole thing?

First, get clear in your brain what your purpose is with this book. What information are you looking for, exactly? It might help to write that down.

Then, find the place in the book that likely includes the information you’re looking for. You can find this in the Table of Contents at the beginning, or in the Index at the end. Head to that spot in the book. If it’s an electronic test, you might be able to search for keywords also.

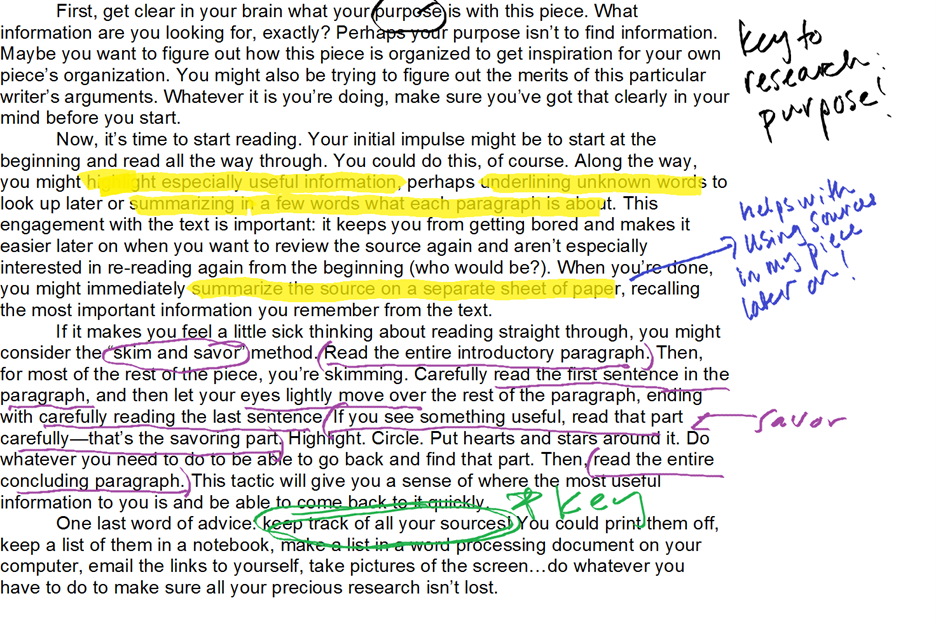

Now, it’s time to start reading. When we have a chapter of a book (or even an article), your initial impulse might be to start at the beginning and read all the way through. You could do this, of course, if you have the time. Along the way, you might highlight especially useful information, perhaps underlining unknown words to look up later or summarizing in a few words what each paragraph is about. Engaging with the text is important: you get less bored and you can find the important information later when you want to review the source again and aren’t especially interested in re-reading again from the beginning (who would be?). When you’re done, you might immediately summarize the source on a separate sheet of paper, recalling the most important information you remember from the text. You should also create a citation now (which saves time later).

If it makes you feel a little sick thinking about reading straight through, you might consider the “skim and savor” method. Read the entire introductory paragraph. Then, for most of the rest of the piece, you’re skimming. Carefully read the first sentence in each paragraph, and then let your eyes lightly move over the rest of the paragraph, ending with carefully reading the last sentence. If you see something useful, read that part carefully—that’s the savoring part. Highlight. Circle. Put hearts and stars around it. Do whatever you need to do to be able to go back and find that part. Then, read the entire concluding paragraph. This tactic will give you a sense of where the most useful information is and help you come back to it quickly.

Example: Annotating a text

Reading Academic Journal Articles

When looking at academic journal articles, you might feel intimidated. These articles are written with highly elevated language, often utilizing terms that are unfamiliar to those who aren’t experts in that particular field. They’re long, too, with LOTS of in-text citations and a massive source list (often upward of a hundred sources!). So, it might feel like you want to skip over them altogether.

But wait!

Journal articles are excellent sources. Instead of being intimidated, understand what’s happening in them so you know what to spend your time looking at.

Tips for Reaching Academic Journals

1. Read the Abstract. This will tell you whether or not you want to dig further. Don’t cite from the abstract, though! If you decide that an article might be helpful, go to the next step.

2. Read the Introduction. This provides context for the study.

3. Skip down to the Results. Once the study is complete, the author(s) will report what information they learned. Skim this section to see if anything is interesting there.

4. Spend time reading the Discussion. This is where the author(s) join the results of their study and what those results mean. This is a great place to look for information that’s both interesting and useful.

One last word of advice when finding sources: keep track of all your sources! You could print them off, keep a list of them in a notebook, make a list in a word processing document on your computer, email the links to yourself, take pictures of the screen, use an archive like Evernote or Pinterest to collect and organize research…do whatever you have to do to make sure all your precious research isn’t lost. Many resources now also include citations in MLA/APA and other formats which you can copy and paste into your files.

So, read, read, read, listen, listen, listen, search, search, search, watch, watch, watch. Take notes. Toss out the stupid stuff and find what is useful. Get good at reading and clicking through your phone to find things.

Using sources

Quoting, Paraphrasing, Summarizing Sources

First, a note: it is difficult to talk about quoting, summarizing and paraphrasing without also talking about in-text citation, which is where you say where you got the information that’s being quoted, summarized, or paraphrased. What you’ll see here, then, is in-text citations (and full citations at the end of this section) for the source we’re using by way of example so you can see how that works.

More information about citation—in the writing itself as well as for a Work Cited (MLA) or References (APA) page—will be linked in the section that follows.

Proper quoting, paraphrasing, and summarizing aren’t just about grammatical correctness; using them is a fine art. You can choose which of the three you want to use at certain times in your work to support your ideas. They all have different effects, so as you’re learning what they are and practicing, consider how a quote’s effect might be different than a summary’s effect, which are both different than a paraphrase.

Before we say anything else, though, we have to tell you that the number one thing to remember when using research in any paper is the following:

MOST IMPORTANT THING ABOUT USING SOURCES

If you use outside sources in any way, shape, or form, you must cite it in the text, even if you don’t use the sources exact words.

The reader assumes that you are the author of all writing and ideas in your writing unless you cite the source!

All right. Now, let’s get down to business:

Quoting sources

Quoting is the easiest way of incorporating outside sources. Unfortunately, because it is the easiest way, it is also not necessarily the best way.

People sometimes have the tendency to dump a bunch of quotes in their papers and think that’ll make them look smart.

Trust us; it doesn’t.

Too much quoting will make you look like you don’t care, you’re lazy, and/or you don’t have an original thought of your own, and it also puts several different styles of writing in the same piece, which can interrupt the flow of ideas and read awkwardly. Sometimes, however, quoting is the most effective way of getting the information down, so if you must, be sure to use the author’s exact words and put quotation marks around it.

Example: Mentioning the author before the quote:

MLA: An example of the difficulty of writing papers appears in Sweet Agony by Gene Olson: “There is no more demanding task than writing. No matter how long one works at it, no matter how many words are produced, room for improvement will always remain” (13).

APA: An example of the difficulty of writing papers appears in Sweet Agony by Olson (1972): “There is no more demanding task than writing. No matter how long one works at it, no matter how many words are produced, room for improvement will always remain” (p. 13).

*Note: The phrase “An example of the difficulty of writing papers appears in Sweet Agony by Gene Olson:” is called a signal phrase or tag. Other examples of signal phrases are “Olson states,” “Olson claims that” and “Olson suggests.” There are many others, too. These phrases help to introduce source material in quoting, summarizing, and paraphrasing. Thoughtful use of tags is important to help cite correctly as well as encourage the flow of your writing.

Example: The same quote without mentioning the author before it. In this example, the citation information follows the quote, in parenthesis:

MLA: “There is no more demanding task than writing. No matter how long one works at it, no matter how many words are produced, room for improvement will always remain” (Olson 13).

APA: “There is no more demanding task than writing. No matter how long one works at it, no matter how many words are produced, room for improvement will always remain” (Olson, 1972, p. 13).

Consider the effect of citing in the parentheses versus using a tag in the sentence itself. If it’s the first time you’re using a source in the text, it’s not a bad idea to use a tag; after that, you can do either.

Quoting sources: Long quotes

For essays written using the MLA documentation style, quotes that are more than four typed lines (not sentences, but lines as they appear on the page), or for essays written using the APA documentation style, quotes that are more than 40 words (or longer), make a block quote. Check this out:

Examples of quoting long/block quote:

MLA: Writing is difficult. Everybody knows this. It has been said over and over through the centuries. As Gene Olson states:

There is no more demanding task than writing. No matter how long one works at it, no matter how many words are produced, room for improvement will always remain. Herein lies the ultimate frustration of writing; herein also lies its bittersweet charm and challenge. It’s like chasing butterflies in a world where there are always more butterflies, each new batch prettier than the last. (13)

APA: Basically the same thing, but use “Olson (1972)” in the tag and (p. 13) in the parentheses.

Note that the indenting takes the place of quotes. Block quotes should be used sparingly, as they break up the flow of the paper and can cause reader impatience.

Finally, when using quotes, make sure you set up the quote in the text with your own ideas and after the quote, interpret it in some way for the reader, such as discussing how it fits in with your other ideas. That will help the reader understand the quote itself and make you more credible to the reader.

Quoting sources: Paraphrasing

Paraphrasing is when you take an exact quote and put it into your own words and writing style, capturing the same ideas as the original. It is approximately as long as the original as you go sentence-by-sentence, putting the original all in your own words. Of course, sometimes you must use the same words as the original (for example, if you’re writing about funerals and the source talks about funerals, you can use the word funeral). Quotation marks go around the exact phrasing that is borrowed from the original, and paraphrases are always cited.

Example of paraphrasing

Original quote: “There is no more demanding task than writing. No matter how long one works at it, no matter how many words are produced, room for improvement will always remain” (Olson 13).

Paraphrase using MLA: As Gene Olson states in Sweet Agony, writing can take a lot out of a person. One can write long and hard, coming up with a ton of text, but one can always do better (13).

APA: Follow the same rules as quoting in APA.

See that? It’s the same idea as the original and the same length, but different words. Can you see how this might have a different effect on a reader than a direct quote?

In case you were wondering, here’s an example of the original quote paraphrased poorly:

Poor paraphrase: Writing is a demanding task. One works a long time at it and

produces many words, but there’s always room for improvement.

This is not good because it is too close to the original, using many of the same words and phrases, and it’s also missing a citation. This would be considered plagiarism.

Quoting sources: Summarizing

Summaries do just that: they sum up the main idea or spirit of the original text. Summaries are significantly shorter than the original text. Though there are no quotation marks (unless you use some of the exact phrasing from the original), you still cite.

Example of summarizing

Original quote: “There is no more demanding task than writing. No matter how long one works at it, no matter how many words are produced, room for improvement will always remain” (Olson 13).

Summary in MLA: Writing is difficult, mostly because it can always be better (Olson 13).

Summary in APA: Writing is difficult, mostly because it can always be better (Olson, 1972, p. 13).

The importance of citation

“Wait,” you may say, “Isn’t it common knowledge that writing is difficult, and there’s always room for improvement? Why would we have to cite this Olson guy if it’s common knowledge?” Good question. Here’s the answer: If you hadn’t thought about including this particular piece of information in your paper until you read Olson’s book, cite it. Again: when in doubt, cite.

Work Cited (MLA)

Olson, Gene. Sweet Agony. Windyridge Press, 1972.

Reference (APA)

Olson, G. (1972). Sweet agony. Grants Pass, OR: Windyridge Press.

Citing sources: Basic citation styles

What is the difference between MLA and APA styles, the most commonly used citation styles in writing classes?

Sometimes the citation style you use is your choice, but most often, your instructor will give you a style he or she would like you to use. The two most common are MLA and APA.

MLA, or Modern Language Association, is used most often in the humanities: English, history, the languages, etc. It is focused on the names of authors; this authorial expertise is highly valued in the humanities.

APA, or the American Psychological Association, is used most often in the sciences: biology, chemistry, sociology, and, as the name suggests, psychology, among others. It is most focused on dates; this is why you see the copyright date noted after the last name when it’s used in a signal phrase in the text. When something was written in values in the sciences.

Citations in both styles have two parts: source information in the actual essay (called an in-text citation) and source information on a separate page that becomes an alphabetical list of all your sources.

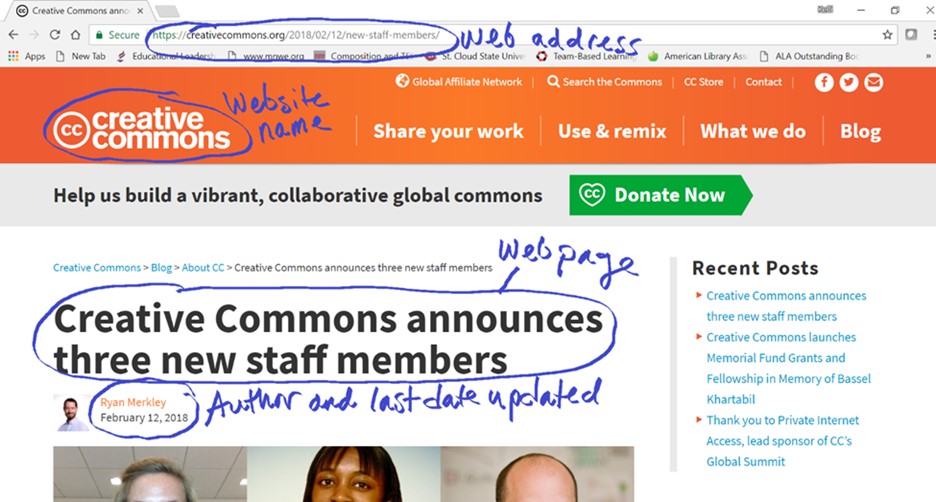

The basic source for formatting is a webpage.

What follows are some suggestions on citations using MLA and APA formatting. This is in no way exhaustive; it is only meant to give you a sense of what you should be thinking about when creating citations. We included some resources in each section that will be helpful for more information.

MLA Citation: The Basics

Let’s say we’re looking at a (fictional) webpage. When creating an in-text citation, you can use a signal phrase or a parenthetical citation (as noted in the previous section). In MLA citation, a signal phrase will mention, at the very least, the author(s) OR, if there’s no author, the title of the work.

Examples of introducing sources with signal phrases

According to Fred Rogers…

As noted in the article, “It’s a Beautiful Day in the Neighborhood,”…

Example of using parenthetical citations

A parenthetical citation is placed after the source material (remember, you cite even if you put the source information in your own words!), and it looks like this:

(Rogers).

Or, if there is no author, then:

(“It’s a Beautiful Day”).

Note that the period goes outside the parentheses and you should use a shortened version of the title.

Creating a Full Citation

Now, you’ve got half the job done. It’s no good having an in-text citation if it doesn’t refer to a source, so on a separate sheet of paper titled “Work Cited,” you’ll list what’s called the full citation for each source. It might look something like this:

Rogers, Fred. “It’s a Beautiful Day in the Neighborhood.” Fred Rogers Superfans,

2015, www.fredrogerssuperfans.com.

OR, if there’s no author:

“It’s a Beautiful Day in the Neighborhood.” Fred Rogers Superfans, 2015, www.

fredrogerssuperfans.com.

Online citation tools

What can be most frustrating about citation is that there are as many ways to cite sources as there are sources. First, know that the basic citation formatting is similar, so when you get the basics down, it makes it easier. Second, there are lots of sources out there to help you make your citations. Here are some of the best:

EasyBib Citation Guides: http://www.easybib.com/guides/citation-guides/

Citing Your Sources: MLA (Williams Libraries): https://libguides.williams.edu/citing/mla

MLA Style Center: 9th Edition (LIU Post): https://style.mla.org/

USER BEWARE: Go ahead and use a citation-generating tool, but the responsibility is yours to make sure the citation is correct. For that reason alone, you need to have an understanding of how citations should look.

Once again…HOW TO CITE A WEBPAGE

As a reminder, the webpage is the basic source type (back in the day, it used to be a print book!). Understanding the general elements that go into a webpage citation provides a solid jumping-off point for other types of citations.

HOW TO CITE A WEBPAGE WITH AN AUTHOR

Full MLA citation format:

Author’s Last name, First name. “Title of the Webpage.” Website, Name of the Publisher (if it’s available), date of publication in day abbreviated month year format, URL.

Full MLA citation example with author:

Reeves, Mosi. “The Race to Save Hip Hop’s Lost Eras.” Pitchfork, Conde Nast, 10

Jan. 2022, https://pitchfork.com/features/article/the-race-to-save-hip-

hops-lost-eras.

In the text: (Reeves).

HOW TO CITE A WEBPAGE WITHOUT AN AUTHOR

Full citation format:

“Title of the Webpage.” Website, Name of the Publisher (if it’s available), date of publication in day abbreviated month year format, URL.

Example of MLA citation without author

“The Race to Save Hip Hop’s Lost Eras.” Pitchfork, Conde Nast, 10 Jan. 2022, https://pitchfork.com/features/article/the-race-to-save-hip-

hops-lost-eras.

In the text: (“The Race”).

Checklist for Citations: MLA Documentation

√ Your list of full sources is titled Works Cited.

√ It is a separate page in your document.

√ You have at least four sources.

√ Sources are alphabetized using the first word in the citation (but not A, An, or The)

√ Format with a hanging indent: the first line in the citation is a full line; subsequent lines are indented using the TAB key.

√ You assure that your in-text citations are correct. For example:

In-text citations

According to “About STOMP Out Bullying”… OR (“About”)

Oyaziwo Aluede, et al., note that… OR (Aluede, et al.).

John Bonford noted that… OR (Andrist)

…as indicated by the “Circle Time” webpage on the Anti-Bullying Alliance website OR (“Circle Time”).

Example of a Works Cited page

Works Cited

“About STOMP Out Bullying.” Stomp Out Bullying, 11. Nov. 2023, https://www.stomp

outbullying.org/about.

Aluede, Oyaziwo, et al. “A Review of the Extent, Nature, Characteristics and Effects of Bullying Behaviour in Schools.” Journal of Instructional Psychology, vol. 35, no. 2, June 2008, pp. 151–58. EBSCOhost, search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=keh&AN=33405328&site=ehost-live.

Bonford, John. Personal Communication. 13 Nov. 2023.

“Circle Time.” Anti-Bullying Alliance, National Children’s Bureau, 2023, https://anti-

bullyingalliance.org.uk/tools-information/all-about-bullying/responding-bullying/ circle-time.

APA Citation: The Basics

As an introduction, let’s look at a fictional webpage. When creating an in-text citation for APA, a signal phrase will mention the author (but only the first initial of the first name as APA maintains gender neutrality) AND the copyright date:

If there is an author: According to F. Rogers (2015)…

If there is no author: As noted in the article, “It’s a Beautiful Day in the Neighborhood” (2015)…

Example pf APA parenthetical citations

An APA parenthetical citation would look something like this:

Author: (Rogers, 2015).

No author: (“It’s a Beautiful Day,” 2015).

You’ll need a separate list of sources for APA citation. It should be titled “References,” your sources should be alphabetized. A full citation might look something like this:

Example of full APA citation

Rogers, F. (2015). It’s a beautiful day in the neighborhood. Fred Rogers Superfans.

www.fredrogerssuperfans.com

OR, if there’s no author:

It’s a beautiful day in the neighborhood. (2015). Fred Rogers Superfans,

www.fredrogerssuperfans.com.

Online citation tools

What can be most frustrating about citation is that there are as many ways to cite sources as there are sources. First, know that the basic citation formatting is similar, so when you get the basics down, it makes it easier. Second, there are lots of sources out there to help you make your citations. Here are some of the best:

EasyBib Citation Guides: http://www.easybib.com/guides/citation-guides/

Citing Your Sources: APA (Williams Libraries): https://libguides.williams.edu/citing/apa

APA Citation Style Guide (LIU Post): http://liu.cwp.libguides.com/APAstyle

USER BEWARE: Go ahead and use a citation-generating tool, but the responsibility is yours to make sure the citation is correct. For that reason alone, it’s worth having an understanding of how citations should look.

Once again…HOW TO CITE A WEBPAGE

As a reminder, the webpage is the basic source type (back in the day, it used to be a print book!). Understanding the general elements that go into a webpage citation provides a solid jumping-off point for other types of citations.

HOW TO CITE A WEBPAGE WITH AN AUTHOR

Full citation format:

Author’s Last name, First initial. (publication year, Month and Day). Title of the

webpage. Website. URL

Full APA citation example with author

Reeves, M. (2022, January 10). The race to save hip hop’s lost eras. Pitchfork.

https://pitchfork.com/features/article/the-race-to-save-hip-hops-lost-eras

In the text: (Reeves, 2022).

HOW TO CITE A WEBPAGE WITHOUT AN AUTHOR

Full citation format:

Title of the webpage. (publication year, Month and Day). Website. URL

Full APA citation example with without author

The race to save hip hop’s lost eras. (2022, January 10). Pitchfork. https://

pitchfork.com/features/article/the-race-to-save-hip-hops-lost-eras

In the text: (“The Race,” 2022).

Checklist for Citations: APA Documentation

√ Your list of full sources is titled References.

√ It is a separate page in your document.

√ You have at least four sources.

√ Sources are alphabetized using the first word in the citation (but not A, An, or The)

√ Use hanging indents: the first line in the citation is a full line; subsequent lines are indented using the TAB key.

√ You assure that your in-text citations are correct. For example:

APA in-text citation examples

According to “About STOMP Out Bullying” (2023)… OR (“About”, 2023)

Aluede, et al. (2008) note that… OR (Aluede et al., 2008).

…as indicated by the “Circle Time” (2023) webpage on the Anti-Bullying Alliance website OR (“Circle Time”, 2023).

√ Special Note: IF you have conducted an interview with someone, it does NOT go on the References list, but it DOES count towards your four sources. Cite it in the text of your proposal like this:

According to K. Hallsten Erickson… (Personal communication, November 16, 2023) OR (K. Hallsten Erickson, personal communication, November 16, 2023).

Example of APA Reference Page

References

About STOMP Out Bullying (2023, 11 November). Stomp Out Bullying. https://www.stompoutbullying.org/about

Aluede, O., Adeleke, F., Omoike, D., & Afen- Akpaida, J. (2008). A Review of the Extent, Nature, Characteristics and Effects of Bullying Behaviour in Schools. Journal of Instructional Psychology, 35(2), 151–158.

Circle time (2023). Anti-Bullying Alliance. National Children’s Bureau. https://anti-bullyingalliance.org.uk/tools-information/all-about-bullying/responding-bullying/circle-time.

ResourceS

“APA Formatting and Style Guide (7th edition).” Purdue University OWL, 2025, https://owl.purdue.edu/owl/research_and_citation/apa_style/apa_formatting_and_style_guide/index.html.

“APA Style.” American Psychological Association, 2025, https://apastyle.apa.org/.

“MLA Documentation Guide.” The Writing Center University of Wisconsin-Madison, https://writing.wisc.edu/handbook/docmla/.

“MLA Formatting and Style Guide.” Purdue University OWL, 2025, https://owl.purdue.edu/owl/research_and_citation/mla_style/mla_formatting_and_style_guide/mla_formatting_and_style_guide.html.

“The Research Paper.” St. Louis Community College, 2025, https://stlcc.edu/student-support/academic-success-and-tutoring/writing-center/writing-resources/the-research-paper.aspx.

“Tips on Writing a Good Research Paper.” American Public University, 16 May 2023, https://www.apu.apus.edu/area-of-study/education/resources/tips-on-writing-a-good-research-paper/.

Media Attributions

- Research © Image by Freepik

- Annotating Text © Kelli Hallsten-Erickson

- Parts of a website