Minnesota’s Civil War: The US Dakota War of 1862

1 Minnesota’s Civil War: The US Dakota War of 1862

With the Country embroiled in Civil War, an ill-advised and poorly administered federal Indian policy led to a short-lived but horrifying war between factions of Dakota and the US Government that traumatized the Minnesota River Valley.

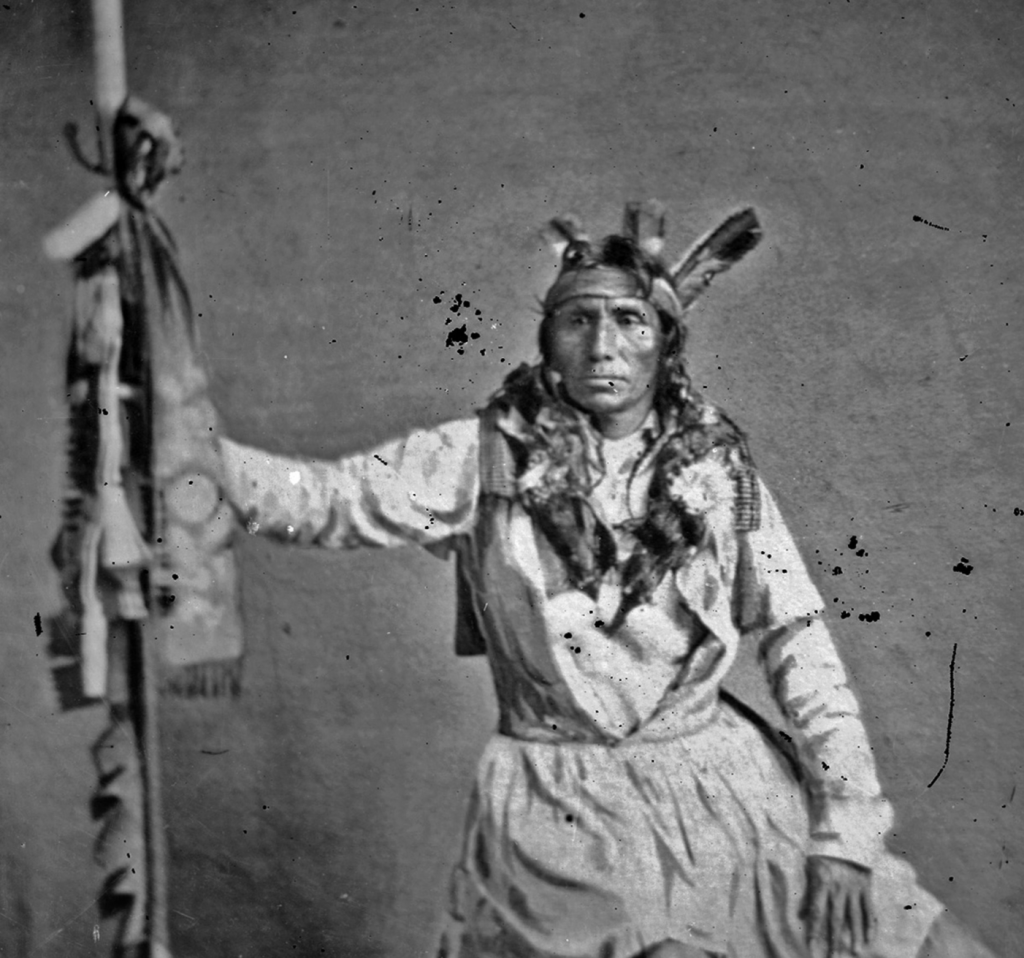

Just before dawn in the early morning of August 18, 1862, a delegation of chiefs led hundreds of young men to Little Crow’s newly constructed frame house on the Dakota reservation in the Minnesota River valley. Roused from sleep, Little Crow, an embattled Mdewakanton Dakota leader recently voted out of any official leadership role, listened as the chiefs explained why they had come at such an odd hour. In a show of bravado fueled by smoldering frustration over dismal conditions on their reservation, four Dakota young men from a nearby village had murdered five white settlers north of the reservation. Members of the soldiers’ lodge, an ancient quasi-military organization mostly comprised of more radical young hunters, were excited and clamoring for war. The chiefs were divided; some spoke in favor of war, others counseled for peace. Little Crow sat in his bed with a blanket draped over his shoulders and listened.[1]

The assembled chiefs and leaders of the soldiers’ lodge discussed two courses of action. They could turn over the four murders to government authorities and endure punishment of unknown severity that was likely to include the reduction or elimination of the already late treaty-mandated annuity payment. Or they could choose to rally the Mdewakanton Dakota and her sister tribes in a general war against a US government weakened and distracted by its own Civil War. Little Crow joined Traveling Hail, Wabasha, and Big Eagle in advocating peace in opposition to the leaders of the soldiers’ lodge, Red Middle Voice, Young Shakopee (Little Six), and Medicine Bottle’s pleas for war. Shakopee argued, “blood had been shed, the payment would be stopped, and the white would take a dreadful vengeance because women had been killed.” Little Crow seemed to be defusing the situation and turning the council toward peace and reconciliation when Red Middle Voice declared that “Little Crow is afraid of the White Man; Little Crow is a coward!”[2]

Years later Little Crow’s son, who was in the room listening to the heated debate, recalled his father’s reaction. Throwing Red Middle Voice’s headdress to the floor, Little Crow countered:

TA-O-YA-TE-DU-TA is not a coward, and he is not a fool! … Braves, you are like little children; you know not what you are doing.

You are full of the white man’s devil-water. You are like dogs in the Hot Moon when they run mad and snap at their own shadows. We are only little herds of buffaloes left scattered; the great herds that once covered the prairies are no more. See! – the white men are like the locusts when they fly so thick that the whole sky is a snowstorm… Kill one – two – ten, and ten times ten will come to kill you…

Yes; they fight among themselves – away off. Do you hear the thunder of their big guns? No; it would take you two moons to run down to where they are fighting, and all the way your path would be among white soldiers as thick as tamaracks in the swamps of the Ojibways. Yes; they fight among themselves, but if you strike at them they will all turn on you and devour you and your women and little children just as the locusts in their time fall on the trees and devour all leaves in one day. You are fools. You cannot see the face of your chief; your eyes are full of smoke. You cannot hear his voice; your ears are full of roaring waters. Braves, you are little children – you are fools. You will die like the rabbits when the hungry wolves hunt them down in the Hard Moon. But after laying out his opposition to what he seems to have felt was a hopeless situation, he added “Ta-o-ya-te-du-ta is not a coward; he will die with you.” Cheers of support filled the room and then poured out onto the grounds surrounding the house. The Mdewakanton Dakota would go to war, with Little Crow leading them.[3]

A Failed Federal Policy

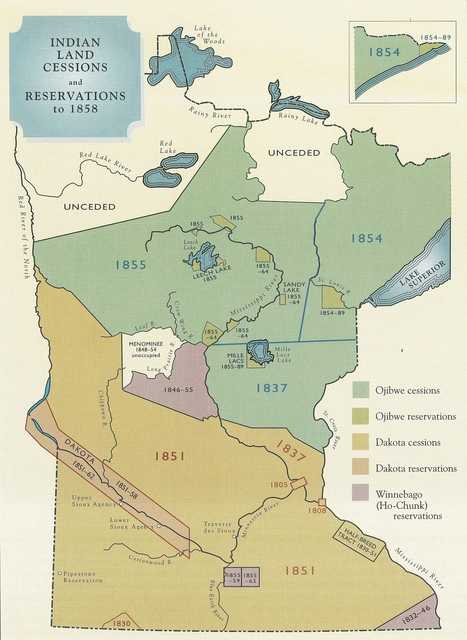

The eastern-most branch of the Dakota people (including the Mdewakanton, Wahpekute, Sisseton and Wahpeton council fires or bands) had occupied what would become Minnesota for countless generations when, beginning around the middle of the seventeenth century, Ojibwa peoples began to enter the region from the east. By the time political control of the region had passed from European powers to the Americans, the Ojibwa occupied what would become northern Minnesota, while the four Dakota bands had settled in the southern portions of the future state. As it had done with other American Indian peoples to the east, the US government entered into dubious treaties with the Dakota in order to acquire legal title to their lands. By the time the federal government established the Minnesota Territory in 1849, treaty making with the Dakota had been going on for over four decades, Dakota had ceded lands east of the Mississippi, and a US Military post, Fort Snelling, stood at the confluence of the Minnesota and Mississippi Rivers (present-day Minneapolis/St Paul). By the summer of 1851, the rapidly expanding nation enticed its government to negotiate for what was commonly called the “Suland,” the vast territory still held by the Dakota in southern Minnesota.[4]

In the face of political pressure and the underlying threat of military force, the Dakota bands signed treaties at Traverse des Sioux in July of 1851 and Mendota early the following month transferring their lands in the Minnesota Territory and the state of Iowa to the US government and agreeing to relocate to a reservation along the upper Minnesota River. The agreements transferred 21 million acres to the US government for less than 15 cents an acre. After initial payments in cash and goods, the bulk of the compensation was retained by the government and the Dakota paid the interest at 5% over fifty years in the form of yearly annuity payments comprised of goods, services, and cash. Further, Dakota treaty signers were in some cases tricked and in other cases induced into signing a separate agreement that provided for the payment of individual trade debts be paid out of the treaty payments. To make matters worse, the US Senate struck out the reservation clauses and, in their place, provided a promise from the President that they could remain on the reservations for at least five years.[5]

In addition to acquiring Dakota lands, federal policy, assisted by well-intentioned but culturally bias missionaries, also sought to assimilate the Dakota people by encouraging private land ownership, framing, and the adoption of white language, culture and religions. These pressures served to divide the Dakota people. The “Blanket Indians,” or those who resisted these assimilation efforts looked down on and called those who chose to cut their hair, change their dress, build frame houses, and farm individual plots “Cuthairs.” A presence of a large number of people of mixed Euro-Dakota ancestry, served only to complicate the situation made increasingly more difficult by the government’s failure to make good on its treaty promises to keep settlers off reservation lands, and make prompt and complete annuity payments. Trade debts taken form treaty payments also remained a problem when Dakota leaders were called to Washington in 1858 for what they believed was an opportunity to discuss the shortcomings in treaty administration. Instead, government negotiators stranded the delegation in Washington for six weeks before inducing the bewildered Dakota to relinquish the northern portion of their reservation. The leaders, including Little Crow, returned to the Minnesota River reservation with their credibility damaged and leadership undermined in the eyes of their people.[6]

By the summer of 1862, the situation had grown desperate for the Dakota. Enduring a harsh winter they watched as cutworms destroyed crops, annuity payments were late as Congress debated paying the cash portion in gold or the new greenback script and traders had cut off credit. The Dakota people were starving.

War in the Minnesota River Valley

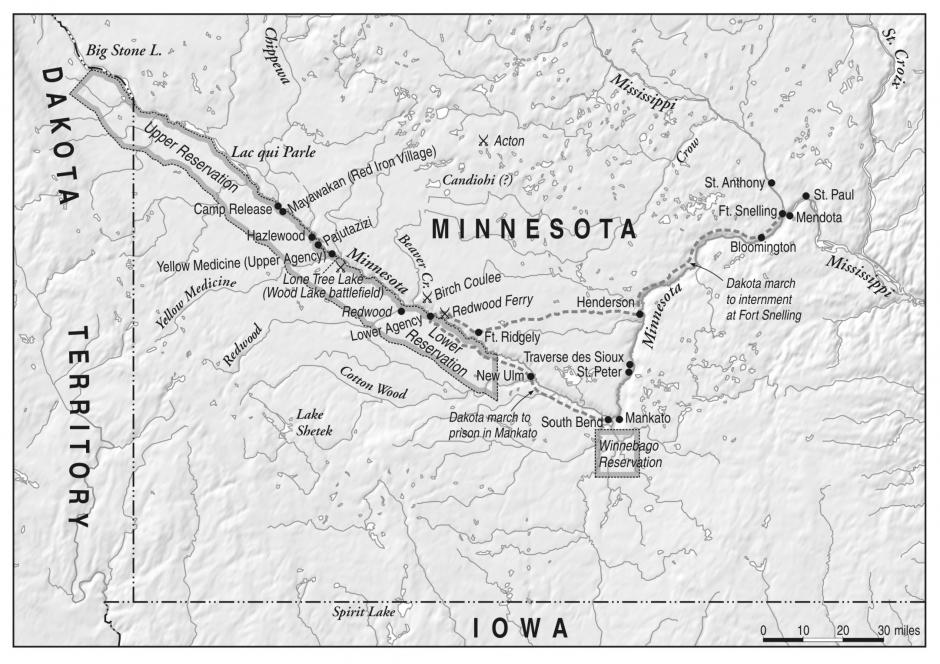

Before the war council concluded, Little Crow ordered an attack on the nearby Lower Sioux Agency to commence at daybreak of August 18th. Big Eagle later recalled, “Parties formed and dashed away in the darkness to kill settlers.” Shortly after dawn Dakota soldiers attacked the agency, killing 21 civilians and government employees but allowing over twice that number to escape. By mid-morning news of the attack had had spread 13 miles to the east and reached Fort Ridgely, a small US military post garrisoned by just 76 men and two officers of Company B of the Minnesota Fifth Regiment. Captain John S. Marsh immediately set out for the Agency with 46 troops but marched directly into an ambush at the ferry crossing. By nightfall, only half of the command made it back to Fort Ridgely. Captain Mash was not among them, having drowned attempting to swim the Minnesota River to escape the Dakota. When news of the hostilities reached the Upper Sioux Agency, a council of Wahpeton and Sisseton leaders was unable to agree upon a single course of action. While the majority opinion appeared to support joining the Mdewakanton because they felt they would be held accountable whether they joined or not, many leaders, including the Paul Mazakutemani, the elected speaker of the Upper bands, refused and instead left the council to warn and aid white settlers. Nightfall brought to close a chaotic day that left the Dakota people and their Anglo-Dakota relatives confused and fragmented and over 200 settlers and US Soldiers dead.[7]

With the lack of a substantial military presence in the vicinity, settlers panicked, fled the region or flocked to Fort Ridgely or to the primarily German-American town of New Ulm. Meanwhile, Little Crow struggled to orchestrate a unified war effort as individual bands of Dakota spread out over the valley killing settlers, taking captives and pillaging farms and small settlements. An unorganized effort to take the town of New Ulm failed on August 19th and the following days soldiers and settlers successfully defended Fort Ridgely from a Dakota attack. On August 23rd 650 Dakota soldiers again attacked New Ulm as settlers, now reinforced by militia units from surrounding communities, fiercely defended a three-block area at the town’s center. The defenders held on to the three-block region, while the Dakota burned the rest of the town. But the 2,000 residents and refugees at New Ulm were low on food, supplies and ammunition and were forced to flee to Mankato 30 miles to the east the following day.[8]

The Dakota lack of unity and the war party’s failure to take Fort Ridgely or New Ulm proved critical as the conflict entered a second stage marked by the arrival of a relief force under the command of Col. Henry Hastings Sibley. On the morning of September 2nd, a detachment of Sibley’s troops sent from Fort Ridgely on a burial detail was surround and besieged for 31 hours by hostile Dakota troops. Sibley himself led a relief party that successfully lifted the siege midmorning of the following day, but not before 13 soldiers and 90 horses were killed and another 47 troops wounded. On the same day, hostile Sisseton and Wahpeton Dakota attacked and then settled in for a three-week siege of Fort Abercrombie far to the northwest located on the Red River of the North that defines the western boundary of Minnesota. Back in the Minnesota River valley, on September 23rd Sibley’s force, now over 1600-strong had unwittingly foiled Little Crow’s ambush attempt at Wood Lake. After about two hours of fighting, Little Crow’s forces withdrew in defeat.[9]

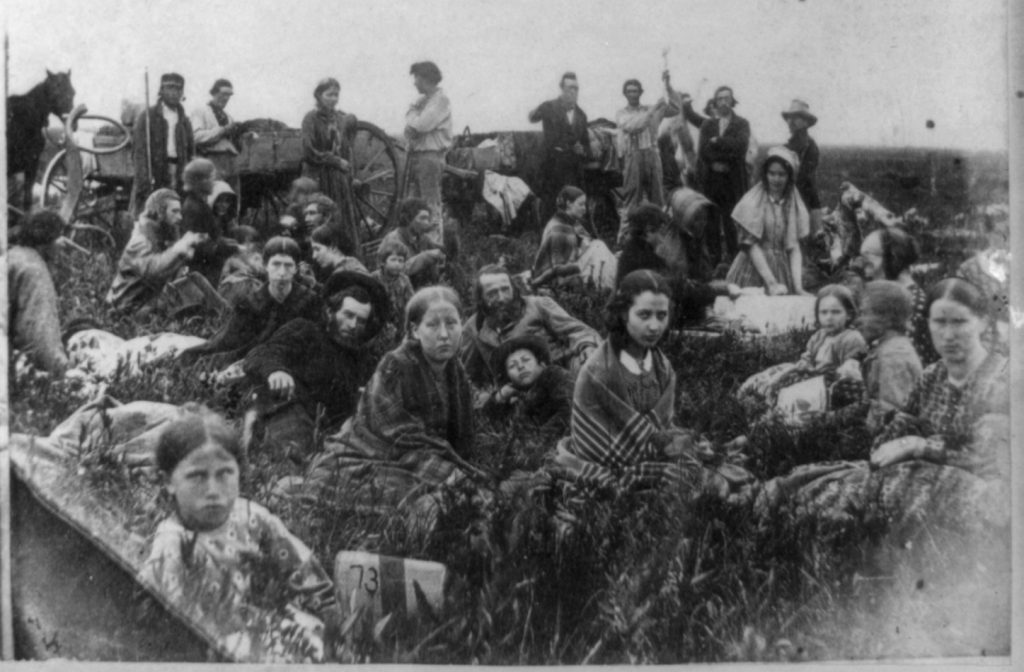

As September neared its end, the growing US military presence drained support from Little Crow’s war effort and peaceful factions of Dakota began gaining more control. The split became so severe that on several occasions, fighting nearly broke out between the peace and war factions of Dakota. After the defeat at Wood Lake Little Crow and most of the war faction fled west into the prairies of the Dakotas while the peace party took control of the 269 white and Anglo-Dakota prisoners and arranged to turn them over to Sibley’s forces on September 26th and 27th at what became known as Camp Release. At the same time 1200 friendly Dakota were taken into custody. Over the following days additional Dakota surrendered to Sibley bringing the total to nearly 2,000.[10]

Retribution

Within days of the surrender, Col. Sibley setup a five-person military tribunal to try Dakota men accused of murdering or assaulting civilians. By November 5th, the commission had tried 392 cases (some in as little as five minutes) and dispensed 303 death sentences in what some historians have called a travesty of justice. The Lincoln Administration intervened and reduced the number of men sentenced to death to 39. After one additional reprieve, the largest mass execution in US history took place as 38 Dakota men were hanged together in Mankato, Minn. on December 26, 1862. Little Crow, who had fled Minnesota after his defeat at Wood Lake, returned the following spring in search of horses. He was shot and killed by a farmer near Hutchinson on July 3, 1863, and his remains were brought back to St Paul and placed on public display. But retribution was not confined to those convicted, In November of 1862 all detained Dakota people were forced to march from the Lower Sioux Agency to Fort Snelling to spend the winter of 1862-1863 in an internment camp and endure a devastatingly high mortality rate (perhaps as many as 300 people died in the camp) before being exiled from the state the following Spring. The following two summers the US military launched two punitive expeditions west of Minnesota in search of the Dakota. Intermittent fighting would continue with the Dakota and their relatives to the west through the Great Sioux War, Little Big Horn and eventually the Massacre at Wounded Knee in 1890.[11]

- Gary Clayton Anderson and Alan Woolworth eds. Through Dakota Eyes: Narrative Accounts of the Minnesota Indian War of 1862. (Saint Paul, Minn.: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 1988), 34; Gregory F. Michno, Dakota Dawn: The Decisive First Week of the Sioux Uprising, August 17 – 24, 1862. (New York: Savas Beatie, 2011), 47-54; Duane Schultz, Over the Earth I Come: The Great Sioux Uprising of 1862 (New York: St Martin’s Press, 1992), 30-32, 39-45. ↵

- Schultz, Over the Earth I Come, 42; Anderson and Woolworth, Through Dakota Eyes, 36. ↵

- Anderson and Woolworth, Through Dakota Eyes, 39-42. ↵

- William Lass, Minnesota: A History. Second Edition. (New York: WW Norton & Company, 1998), 40-45, 82-86, 108; “A Treaty Story.” Minnesota Historical Society online resource. Available online as of January 21, 2012 at: http://www.mnhs.org/places/historycenter/exhibits/territory/territory/treaty/index.html ↵

- “A Treaty Story,” available at: http://www.mnhs.org/places/historycenter/exhibits/territory/territory/treaty/index.html; Lass, Minnesota: A History, 108-112; “TREATY WITH THE SIOUX—MDEWAKANTON AND WAHPAKOOTA BANDS, 1851.” Indian Affairs: Laws and Treaties Available online as of January 22, 2012 at: http://digital.library.okstate.edu/kappler/vol2/treaties/sio0591.htm; “TREATY WITH THE SIOUX—SISSETON AND WAHPETON BANDS, 1851.” Indian Affairs: Laws and Treaties Available online as of January 22, 2012 at: http://digital.library.okstate.edu/kappler/vol2/treaties/sio0588.htm. Regarding 15 cents per acre. The “A Treaty Story” site uses 7.5 cents per acre, but I believe that is only considering the Treaty of Traverse des Sioux. When the payment from the Treaty of Mendota is added to the sum and then divided by the 21 million acres, I ended up with 14.6 cents or so. $1,665,000 (Traverse) + $1,410,000 (Mendota) = $3,075,000 / 21,000,000 = .146. ↵

- Annette Akins, Creating Minnesota: A History From the Inside Out. (St Paul, Minn.: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2007), 44, 49-52; Barbara Newcombe, “The Sioux Sign a Treaty in Washington in 1858,” Minnesota History vol. 45 (Fall 1976); The Dakota Conflict. PBS Video, 1992. ↵

- Carley, The Dakota War of 1862, 12-16, 17-19; Michno, Dakota Dawn, 166-67, 399-401; Anderson and Woolworth, Through Dakota Eyes, 36, 69. ↵

- Carley, The Dakota War of 1862, 32-40. ↵

- Carley, The Dakota War of 1862, 53-63. ↵

- Carley, The Dakota War of 1862, 64-67. ↵

- “US Dakota War of 1862,” Minnesota Historical Society. Available online as of Feb. 18, 2012 at: http://www.historicfortsnelling.org/history/us-dakota-war; Carley, The Dakota Conflict of 1862, 69-92. ↵