Minnesota’s Civil War: The US Dakota War of 1862

3 Analyzing Sources: Little Crow’s Speech

In the preceding account of the U.S. Dakota War of 1862, a speech given by Little Crow is quoted at length. Little Crow purportedly delivered the speech during a council at which the Dakota war faction decided to go to war against the US government. The following activity provides us an opportunity to learn more about that speech and contemplate how historians should best use it when investigating the Dakota War Faction’s decision to go to war.

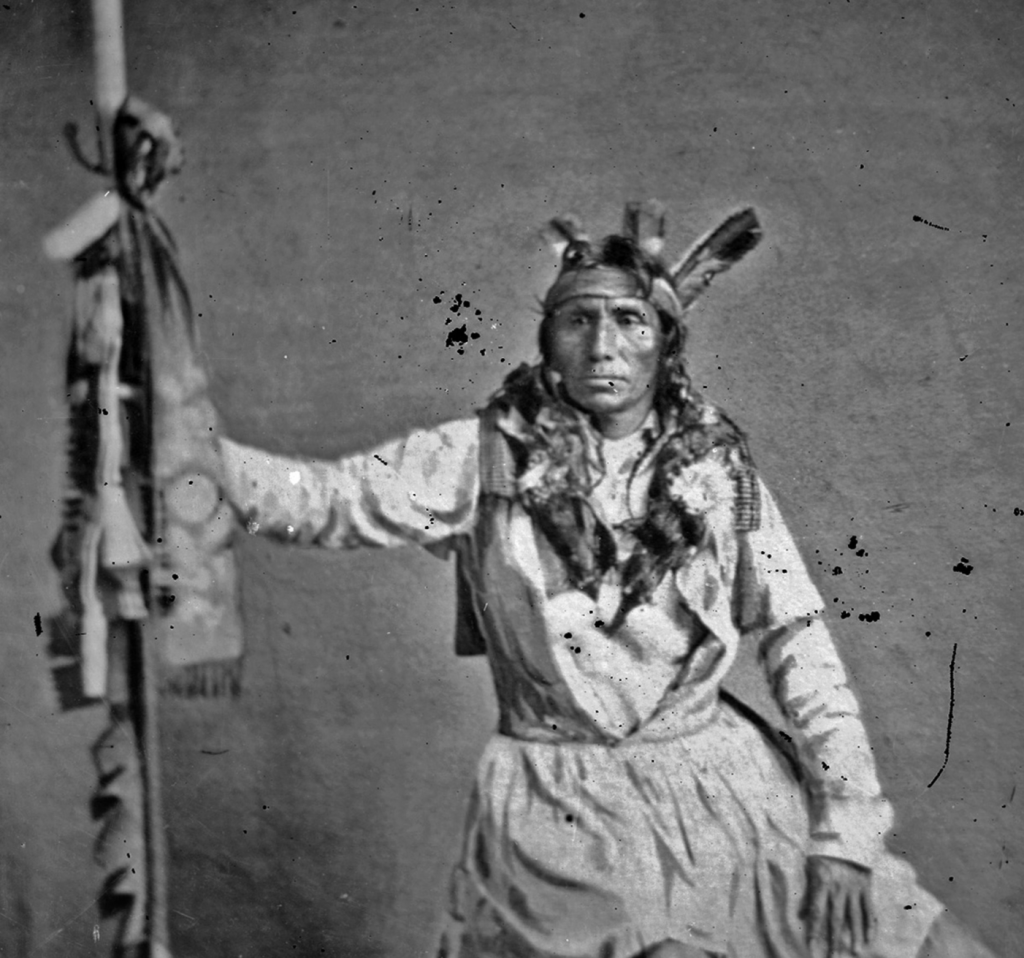

About Little Crow

“Little Crow or Taoyateduta or His Red Nation was born at Kaposia in about 1810…. In 1846 he succeeded his father as leader of the Mdewakanton band but sustained gunshot wounds to both wrists in defeating his half-brother for the position…. In the 1850s he was recognized as the spokesman for all the Mdewakanton bands. By the 1860s he had accepted some of the white man’s ways but refused to adopt anything that would compromise his Dakota religious beliefs….”[1]

Little Crow’s Speech

August 18, 1862

TA-O-YA-TE-DU-TA is not a coward, and he is not a fool! When did he run away from his enemies? When did he leave his braves behind him on the war-path and turn back to his teepees? When he ran away from your enemies, he walked back on your trail with his face to the Ojibways and covered your backs as a she-bear covers her cubs! Is Ta-o-ya-te-du-ta without scalps? Look at his war-feathers! Behold the scalp-locks of your enemies hanging there on his lodge-poles! Do they call him a coward? Ta-o-ya-te-du-ta is not a coward, and he is not a fool. Braves, you are like little children; you know not what you are doing.

You are full of the white man’s devil-water (rum). You are like dogs in the Hot Moon when they run made and snap at their own shadows. We are only little herds of buffaloes left scattered; the great herds that once covered the prairies are no more. See! – the white men are like the locusts when they fly so thick that the whole sky is a snowstorm. You may kill one – two – ten; yes, as many as the leaves in the forest yonder, and their brothers will not miss them. Kill one – two – ten, and ten times ten will come to kill you. Count your fingers all day long and white men with guns in their hands will come faster than you can count.

Yes; they fight among themselves – away off. Do you hear the thunder of their big guns? No; it would take you two moons to run down to where they are fighting, and all the way your path would be among white soldiers as thick as tamaracks in the swamps of the Ojibways. Yes; they fight among themselves, but if you strike at them they will all turn on you and devour you and your women and little children just as the locusts in their time fall on the trees and devour all leaves in one day. You are fools. You cannot see the face of your chief; your eyes are full of smoke. You cannot hear his voice; your ears are full of roaring waters. Braves, you are little children – you are fools. You will die like the rabbits when the hungry wolves hunt them down in the Hard Moon (January). Ta-o-ya-te-du-ta is not a coward; he will die with you.[2]

About Little Crow’s Speech

Through Dakota Eyes

“When the Rice Creek delegation arrived, Little Crow was resting from an early morning hunt. He reacted strongly with an impassioned speech to the news of the Acton affair. His young son, Wowinape, stood beside him and memorized his words. On three separate occasions, Wowinape described the confrontation to Hanford L. Gordon, an attorney. With the aid of the Reverend Stephen Riggs, Gordon translated Little Crow’s speech and included it in two books published in 1891 and 1910.”[3]

Dakota Dawn

“The Speech in its popular form was passed down orally from Little Crow’s 15-year-old son, Wowinape, who was in the room and supposedly memorized the words. He did not record the talk until he gave the story to attorney and author Hanford L. Gordon, who reproduced it in two books of poetry published in 1891 and 1910. The white reiteration of Little Crow’s words may more accurately characterize our fondness for historical irony than actual fact.”[4]

Analyzing the Speech

When historian attempt to explain the immediate decision by the Dakota war faction to go to war against the United States, they often discuss Little Crow’s role and recount the speech you read above. Most often the speech is presented as words directly spoken by Little Crow with little explanation of how the speech came to be added to the historical record. You saw an example of how the speech is typically used when you read the narrative earlier in this lesson.

But history is more complicated and nuanced than we often realize. The two excerpts from Through Dakota Eyes and Dakota Dawn provide a bit more information about the speech. Understanding a bit more about the speech and how it came to be added to the historical record invites us to think more critically about the source, and how best it should be used in studying the cause of the US Dakota War. Having read the narrative that places the speech in context, having read the speech, and having reviewed the two excerpts relating to the speech, answer the following questions:

- How did Little Crow’s speech come to be added to the historical record surrounding the U.S. Dakota War?

- What details about how the speech was added to the historical record might impact its perspective?

- How should the speech best be used or explained when historians attempt to analyze how and why the Dakota war faction decided to go to war against the United States?

- Gary Clayton Anderson and Alan Woolworth eds. Through Dakota Eyes: Narrative Accounts of the Minnesota Indian War of 1862. (Saint Paul, Minn.: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 1988), 39. ↵

- Anderson and Woolworth eds. Through Dakota Eyes, 40-42. ↵

- Anderson and Woolworth eds. Through Dakota Eyes, 39 ↵

- Gregory F. Michno, Dakota Dawn: The Decisive First Week of the Sioux Uprising, August 17 – 24, 1862. (New York: Savas Beatie, 2011), 54n ↵