I Fight No More Forever: The Nez Perce War of 1877

7 Analyzing Sources: Chief Joseph – Good Words

In the preceding narrative, we learned about the role Chief Joseph played in the Nez Perce War of 1877. While other Nez Perce leaders were more responsible for the band’s celebrated military strategy, Chief Joseph is often given credit for masterminding the fighting retreat primarily because he was the only Nez Perce leader to survive the war. That he was well-known to General Howard and other U.S. military personnel also led the contemporary press to exaggerate his leadership role during the conflict. Finally, his now famous “I Fight No More Forever” surrender speech further cemented his historical legacy as did his persistent, well-reasoned advocacy for his people after the war’s conclusion.

The following activity focuses on Chief Joseph’s post-war advocacy. First, review the biographical sketch from the Smithsonian National Gallery. Then read the excerpt from a speech Chief Joseph gave in 1879. Finally, respond to the questions following the speech.

About Chief Joseph

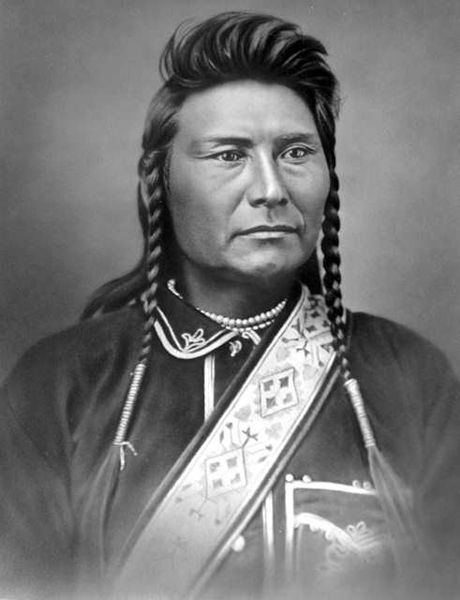

The following excerpt is from the Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery[1]

Born in the Wallowa Valley in northeastern Oregon among the Nez Perce (Niimíipuu), Chief Joseph was also known as Young Joseph. His Nez Perce name means “Thunder traveling to higher areas.” His father, Old Joseph, gave up cooperating with the whites when they attempted to drastically reduce his reservation during the gold rush. Young Joseph carried on this policy after his father’s death in 1871.”

“Although celebrated for his skill in battle, Joseph worked tirelessly for peace with U.S. government authorities. In 1877, under the threat of forced removal from his traditional homelands in Oregon’s Wallowa Valley, Joseph reluctantly began leading his followers toward a reservation in Idaho. However, after a group of warriors killed several white settlers in retaliation for earlier violence, Joseph redirected his party toward the lands of the Crow (Apsaalooke), an allied tribal nation in Montana. In response, federal soldiers began their pursuit of them. The outnumbered Nez Perce embarked on a skillful retreat, at times eluding American forces and at other times repulsing their military advances. General William Tecumseh Sherman remarked that “the Indians throughout displayed a courage and skill that elicited universal praise. . . . [They] fought with almost scientific skill.”

When the Crows refused to come to their aid, Joseph decided to seek sanctuary in Canada. After traveling 1,170 miles with his band of followers, Joseph was intercepted only miles from the Canadian border. He surrendered there on October 5, 1877, stating, “From where the sun now stands, I will fight no more forever.”

Joseph and his people were taken to a reservation in Oklahoma. Although Joseph visited President Rutherford B. Hayes to demand that his people be returned to the Northwest, this did not happen until 1885. Joseph died on the Colville Reservation in Washington State in 1904.[2]

Chief Joseph – Good Words, 1879

I am glad I came [to Washington D.C.]. I have shaken hands with a good many friends, but there are some things I want to know which no one seems able to explain. I cannot understand how the Government sends a man out to fight us, as it did General Miles, and then breaks his word. Such a government has something wrong about it. I cannot understand why so many chiefs are allowed to talk so many different ways, and promise so many different things. I have seen the Great Father Chief [President Hayes]; the Next Great Chief [Secretary of the Interior]; the Commissioner Chief [Commissioner of Indian Affairs]; the Law Chief [General Butler]; and many other law chiefs [Congressmen] and they all say they are my friends, and that I shall have justice, but while all their mouths talk right I do not understand why nothing is done for my people. I have heard talk and talk but nothing is done. Good words do not last long unless they amount to something. Words do not pay for my dead people. They do not pay for my country now overrun by white men. They do not protect my father’s grave. They do not pay for my horses and cattle. Good words do not give me back my children. Good words will not make good the promise of your war chief, General Miles. Good words will not give my people a home where they can live in peace and take care of themselves. I am tired of talk that comes to nothing. It makes my heart sick when I remember all the good words and all the broken promises. There has been too much talking by men who had no right to talk. Too many misinterpretations have been made; too many misunderstandings have come up between the white men and the Indians. If the white man wants to live in peace with the Indian he can live in peace. There need be no trouble. Treat all men alike. Give them the same laws. Give them all an even chance to live and grow. All men were made by the same Great Spirit Chief. They are all brothers. The earth is the mother of all people, and all people should have equal rights upon it. You might as well expect all rivers to run backward as that any man who was born a free man should be contented penned up and denied liberty to go where he pleases. If you tie a horse to a stake, do you expect he will grow fat? If you pen an Indian up on a small spot of earth and compel him to stay there, he will not be contented nor will he grow and prosper. I have asked some of the Great White Chiefs where they get their authority to say to the Indian that he shall stay in one place, while he sees white men going where they please. They cannot tell me.

…

When I think of our condition, my heart is heavy. I see men of my own race treated as outlaws and driven from country to country, or shot down like animals.

I know that my race must change. We cannot hold our own with the white men as we are. We only ask an even chance to live as other men live. We ask to be recognized as men. We ask that the same law shall work alike on all men. If an Indian breaks the law, punish him by the law. If a white man breaks the law, punish him also.

Let me be a free man, free to travel, free to stop, free to work, free to trade where I choose, free to choose my own teachers, free to follow the religion of my fathers, free to talk, think and act for myself — and I will obey every law or submit to the penalty.

Whenever the white man treats the Indian as they treat each other then we shall have no more wars. We shall be all alike — brothers of one father and mother, with one sky above us and one country around us and one government for all. Then the Great Spirit Chief who rules above will smile upon this land and send rain to wash out the bloody spots made by brothers’ hands upon the face of the earth. For this time the Indian race is waiting and praying. I hope no more groans of wounded men and women will ever go to the ear of the Great Spirit Chief above, and that all people may be one people.[3]

Analyzing the Speech

- Specifically, what is Chief Joseph referring to when he says: “It makes my heart sick when I remember all the good words and all the broken promises”? What larger issue does Joseph’s complaints reveal about the U.S. Federal Government’s diplomatic efforts with the Nez Perce and other indigenous nations?

- In addition to issuing complaints about broken promises, Chief Joseph also advocates for equal treatment. Identify two quotes from the above source in which Chief Joseph argues that his people should be treated equally to white people.

- Chief Joseph questions the authority of the federal government to confine indigenous people to reservations. What does he say is the impact of confining people to small reservations? Use quotations to support your points here.

- "Chief Joseph," National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institute, 2008. Available online at: Chief Joseph (ca. 1840–1904) | (si.edu) as of May 6, 2023. ↵

- "Chief Joseph," National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institute, 2008. Available online at: Chief Joseph (ca. 1840–1904) | (si.edu) as of May 6, 2023. ↵

- "Chief Joseph Speaks Selected Statements and Speeches by the Nez Percé Chief," PBS The West. Available online at: PBS - THE WEST - Chief Joseph Speaks as of May 6, 2023. ↵

Tell General Howard that I know his heart. What he told me before I have in my heart. I am tired of fighting. Our chiefs are killed. Looking Glass is dead, Tu-hul-hil-sote is dead. the old men are all dead. It is the young men who now say yes or no. He who led the young men [Joseph's brother Alikut] is dead. It is cold and we have no blankets. The little children are freezing to death. My people -- some of them have run away to the hills and have no blankets and no food. No one knows where they are -- perhaps freezing to death. I want to have time to look for my children and see how many of them I can find. Maybe I shall find them among the dead. Hear me, my chiefs, my heart is sick and sad. From where the sun now stands I will fight no more against the white man.