4 Proxemics

Proxemics

The field of of proxemics deals with four interrelated topics – interpersonal space, crowding, territoriality, and privacy – that all generally refer to how people use space. It is always important to remember that people operate within an environment. We are always using space within the environments we inhabit. Throughout our lives, we have learned thousands of rules about how the culture we grow up in mandates using space. We have a general sense of how much space to give someone in line in the grocery store, when space can be designated as “ours” vs. “someone else’s”, and whether we feel comfortable approaching someone or being approached. Proxemics is the study of these and other rules and how people use these rules to manage the spaces in their lives. Because proxemics is such a wide-ranging topic, this chapter will work a little differently than the others. It will be broken down into four mini-chapters, with each mini-chapter covering one of the four areas of proxemics. Each mini-chapter will have its own story and summary.

Section 1: Interpersonal Space

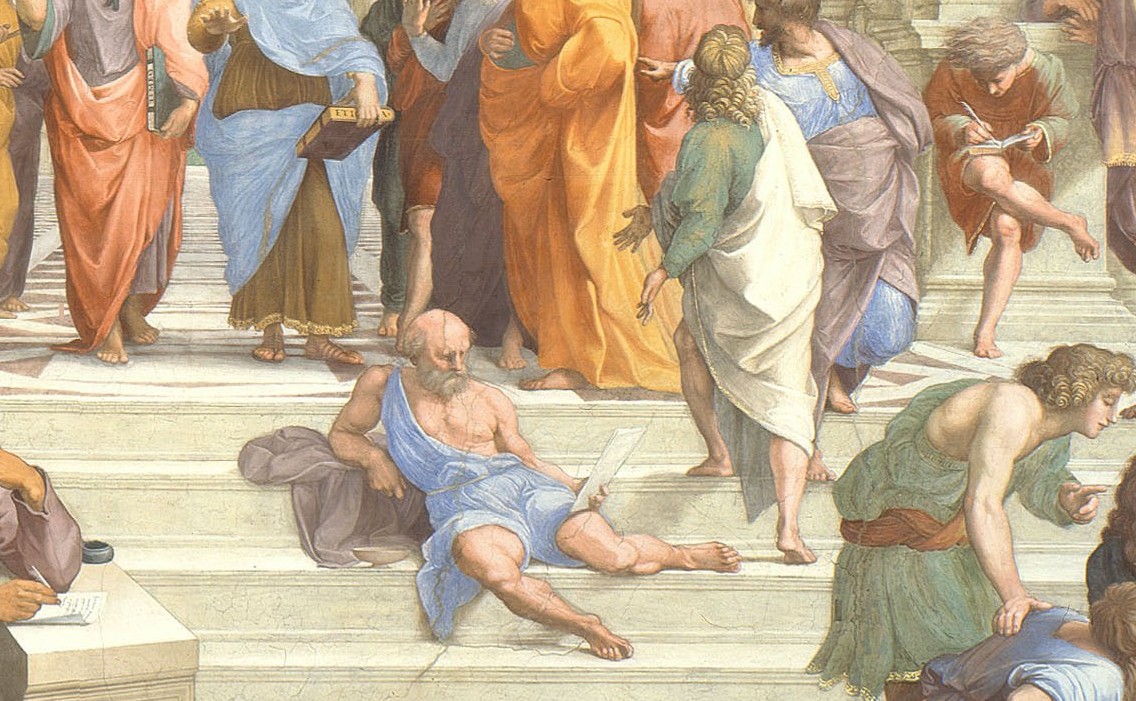

The School of Athens

One of the best known works of art by the Renaissance master Raphael (Raffaello Sanzio da Urbino) is called “The School of Athens”. It depicts many philosophers, mathematicians, and thinkers of the Classic period. It is a fresco painted on a wall in a room in Vatican City. Above the painting is a depiction of a cherub along with the phrase “Seek Knowledge of Causes”. We know that the two figures in the center represent Plato and Aristotle. They are the Classic philosophers most connected to creating a system of logically determining causation. It is they who were most interested in understanding how we come to know why something happens. Beyond that, however, art historians must make inferences about who all the rest of the figures are supposed to represent. Raphael left no notes that have survived regarding who all these people are supposed to be. However, we can make inferences because Raphael included in the painting an implicit understanding of how people use space to manage their social interactions. As he imagined all these people interacting at the same time (in some cases, their births differ by hundreds of years and thus they could never have been in the same room with each other) he used his understanding of how people use space to imagine how everyone would be grouped together.

Let’s begin our study of the painting with a look at the figures in the lower left section.

Notice how all these figures are standing closer to one another than they are to many of the others in the painting. This creates a sense that these people are supposed to be a group. Also notice how some people are closer to each other than others. Art historians believe this is meant to depict some of these people’s ideas being more connected to each other than to others. In some cases, they might be students and mentors. In other cases, one may have built their scholarship off of the other’s ideas. Regardless, art historians have settled into a general agreement that all these people are supposed to be mathematicians. The primary group of four in the most lower left of the painting are believed to be Archimedes – who creating a mathematical equation to predict when an object would float in water, Pythagoras – famous for his Pythagorean Theorem used in geometry (a2 * b2 = c2), Abu al-Walid Muhammad ibn Ahmad ibn Rushd (known to the Romans as Averroes) – a Muslim scholar who applied philosophy and logic to the study of astronomy (among many other wide ranging interests), and Anaximander – an early proponent of using observation to understand the natural world and possibly a teacher of Pythagoras. The two figures off to the right are believed to be people somewhat connected to the mathematicians but notice that Raphael has included space between them to represent that they are not as connected as the four are to each other. The figure wearing purple is believed to be Heraclitus, a philosopher who advocated that mathematics and observation proved that everything is changing all the time. The quote “It is not possible to step into the same river twice” is often attributed to him. Notice how he has his back turned to the figure wearing yellow and blue. This figure is believed to be Parmenides who used mathematics and observation to argue that change is impossible and reality is timeless. Here space and bodily orientation are used to depict that the ideas of these two individuals have a similar source, but that they are fundamentally at odds with one another.

There are many other such groups in this painting which art historians use to make inferences on the identity of the figures. However, we will focus only on one other, the figure laying on the stairs wearing blue just below the central two.

Notice how no one is interacting with this person. In fact, they aren’t even looking at him. This is believed to be Diogenes, one of the founders of the philosophical school of Cynicism. Diogenes was a piece of work. He believed in being an extreme non-conformist against society and social norms. He would act in ways that were considered rude and strange, both for the time and today. It is said he slept in a ceramic jar in the Athens marketplace. He believed Plato was wrong about Plato’s interpretation of the philosophy of Socrates (Plato was Socrates’s student and worked closely with Socrates for years while Diogenes was not and did not). Supposedly, Diogenes would show up at lectures Plato was giving and deliberately distract

the audience. Some sources say he would show up with food and encourage the audience to eat during the lecture. Others say he would interrupt Plato’s lecture and argue with the philosopher. There is a statue of Diogenes in Sinop, Turkey (possibly Diogenes’s home town) showing him holding a lamp because stories say he would carry a lamp around during the day, walk up to people, and hold the lamp up to their face explaining that he was looking for an honest man. He would always say he had not yet succeeded.

He is also known for mocking Alexander the Great to his face when Alexander visited Corinth. Take a moment to imagine who this guy is and think if you have ever interacted with a person like this before. His house is a jar, he tells everyone around him that they are deceitful and corrupt, and he is noted for walking up to not one, but two of the most prominent historical figures of his era – people whose names are still known 2,300 years later – and being distinctly rude to them. It should come as no surprise that Raphael believed that no one would want to interact with this man. Raphael uses spacing, gaze direction, and body orientation to indicate that Diogenes is very much off on his own. He is nearby Plato, one of the central figures of the painting, but they are by no means in conversation with one another or even tolerating each others company. Perhaps Diogenes is waiting for Plato to descend the stairs so he can disrupt Plato’s philosophizing some more.

Interpersonal Space

We will use the term interpersonal space to refer to the general topic area of how much space feels comfortable to give other people when we interact with them. It’s possible you have heard the term “personal space” to refer to this topic. However, we will use the term interpersonal space because as the term “personal space” will be used in a more specific way. So, interpersonal space will refer to the general topic and personal space will refer to a specific amount of space given with specific people. More details about this will be provided below.

Interpersonal space is the most researched topic in the field of proxemics. However, most studies on interpersonal space seek to answer smaller scale questions about individuals. They ask questions like “Does interacting with particular people feel uncomfortable if you are at one distance vs. another?” and “How do our feelings of comfort differ if we change either the person we are interacting with or the distance we are interacting from?”. To date, we do not have a large-scale, integrative theory about why we have interpersonal space. We know how individuals tend to exist within interpersonal space and the important contexts that can alter and adjust the rules people follow when interacting with others. However, we do not know many of the whys about interpersonal space.

The first rule of interpersonal space is: Who Matters. Whom one is interacting with changes how much space people feel they need to feel comfortable. There tend to be four zones of space and we tend to move to the edges of each zone depending on whom we are interacting with. Within each category, a general range of how much space is used for each one is given but note that these are ranges are flexible. We will discuss the reasons for this flexibility later in the chapter.

Intimate Space: Intimate space is the amount of space we give to our closest relationships. Generally, only intimate partners, close family, and pets are allowed within intimate space. If anyone else were to come into this space, we tend to feel uncomfortable and mildly upset. Intimate space tends to be between 0-0.5 feet.

Personal Space: Personal space refers to the amount of space we give to close friends. We tend to stand much closer to our close friends than we are to conversation partners we don’t know. Personal space tends to be between 2.5-4 feet.

Social Space: Social space is for anyone we are engaged with in a back-and-forth interaction. We may not know the people we engage with in these interactions, but we are open to conversations with these people. Many business interactions are conducted in social space. We might be bothered by a random stranger that we don’t want to interact with entering our social space, but generally most people are welcome. Social space exists between 4-12 feet.

Public Space: Public space is for anyone in the general public. Public speakers talking to a general audience tend to use this level. We tend to not be bothered by anyone coming into our public space. Public space exists anywhere between 12 and 30 feet.

The second rule of personal space is that different cultures have different levels that the zones of space exist in. Some cultures are referred to as contact cultures. In contact cultures, the zones of space tend to be smaller and closer together. Public space might be 6 feet, Social 3, Personal 1, and intimate 0. In some Middle Eastern cultures, it would be viewed as strange to be in conversation with someone and not be in direct, physical contact with them. Other cultures are referred to as non-contact cultures. In non-contact cultures, space is extended. Public space might be 12, Social 6, Personal 3, and Intimate 0.5. In these cultures, close contact can be uncomfortable, even among close relationships. Even interactions like being in line at the grocery store might become uncomfortable with people from non-contact cultures. This distinction is often a source of misunderstanding when people from a contact culture interact with people from a non-contact culture. For example, I was born into an extreme non-contact culture (the Upper Great Plains of North America). However, during graduate school, I encountered many people who were born into contact cultures but were advancing their educations abroad. There was a master’s student from Qatar whom I would drink tea with once a week. Subconsciously, he would grip my elbow during conversations before remembering that I found such contact extremely uncomfortable for an informal affiliation based around work. To me, that was a very intimate space type of interaction, but to him it was a social space interaction.

We don’t know much about why a culture develops into a contact vs. non-contact culture. We do know that there seems to be a correlation with geography, but why that correlation exists is still a mystery. Contact cultures tend to develop closer to the equator and non-contact cultures tend to develop at latitudes further away from the equator. This can be seen in that most Middle Eastern, northern African, southern European, tropical Asian, Central American, and Mexican cultures are contact cultures. On the other hand, the United States and Canada as well as north Asian, northern European, and Australian cultures tend to be non-contact. This relationship does not hold in every single situation, however, most notably with southern African cultures tending to be contact cultures. However, without an understanding of why that correlation might exist, we don’t have a way of understanding or contextualizing that relationship. It could be a spurious relationship that doesn’t mean anything, it could be just a curious quirk of cultural development, close contact could be somehow beneficial to survival in environments closer to the equator, or avoiding close contact could benefit survival in environments further from the equator. No one is sure at this moment.

The third rule of interpersonal space is that interpersonal space moves with the person. Our zones of interpersonal space are always centered on us. Interpersonal space is tied to our physical bodies. However, interpersonal space is shaped in an odd way. We tend to require less interpersonal space around our feet, want more interpersonal space around our hips and want the most interpersonal space up toward the head. The shape could be visualized as a cone with the narrow end at the feet that moves up to the hips and then the sides go mostly straight up from the hips to the head. This can be seen when people get too close to someone and that person feels uncomfortable. The person who is having their space invaded tends to lean back at the hips but leave their feet stationary. This is because the person feels most uncomfortable with the closeness to head and hips. Closeness to the feet is not nearly as bothersome.

Section Summary

Interpersonal space refers to how much space we are comfortable giving others given our relationship with them. There are four zones of interpersonal space, public space, social space, personal space, and intimate space. Who is welcome in each zone depends on our relationship with that person. Different cultures also tend to adjust the ranges of which relationships are welcome in which spaces. Finally, interpersonal space is centered on a person’s body and tends to be shaped like a cone or inverted birthday hat with the pointed end at the feet.

Section 2: Crowding

Hungary’s Bold Income Tax Initiative

In February 2019, the president of Hungary announced a bold policy initiative. In fact, it was one of the largest investments in social programs in Hungary’s history and took the country from one of the lowest investors in social programs in Europe to one of the highest. The big headline from the announcement was that women citizens of Hungary that have four or more children would be exempt from income tax for the rest of their lives. In addition, he announced several subsidy programs to help with costs associated with raising multiple children that families could take advantage of if they had fewer than four children. These programs include things like government help paying for daycare, groceries, and diapers.

The introduction of this policy may come as a surprise to some. After all, the estimated human population of Earth has just passed 8 billion people. Keeping all these people alive, fed, and growing requires an enormous amount of resources. So why would a government that for years has avoided investing in social programs that reduce the cost of having children suddenly make a massive investment in incentivizing its population to have children?

The answer to this question has a lot to do with how we think about crowding in modern times. For multiple centuries now, the idea of overpopulation has sunk into the deep levels of peoples’ ideas of how the world works. However, to truly understand the idea of crowding and how crowding works in relation to human populations and demographics we must examine both the history of crowding and how ideas about crowding have changed.

Crowding

The idea of crowding faces what is called a levels-of-analysis problem. Imagine this type of problem as levels of magnification. If you are zoomed all the way in, you can see one set of important elements, processes, and conflicts. But if you zoom out one level, you see an entirely different set of important elements, processes, and conflicts. And if you zoom all the way out, the things that seemed very important at the smaller levels don’t seem to matter at all at the largest levels.

Individual level

On an individual level, crowding is very much related to the idea of interpersonal space. When our interpersonal space is being violated, we tend to feel crowded. This also means that on the individual level, feelings of being crowded are very context dependent. We could have huge numbers of family and loved ones around us and not feel crowded at all. However, we could be in an empty room with one other stranger and feel very crowded. Return to the chapter on Personal Space for a review of the contexts and situations that lead to individuals feeling crowded.

Group level

When we expand out to the group level, things look a little bit different than they did with interpersonal space. Context still matters regarding who the people are that around you for whether or not you feel crowded. For instance, groups of nuclear families that are all related by a common bond can come together in a relatively small space and not feel crowded. Think about loving families that all gather in Grandma’s small house for a holiday meal. On the other hand, two rival groups may need to have a buffer zone between them lest they invite unnecessary conflict between one another. Think about the rival gangs in works like West Side Story or The Outsiders. In both of those cases, rival groups have a well defined territory that is known by both groups and when that territory is breached, there is conflict. So the who still matters in group level research. However, research on crowding at the group level is much more concerned with basic living processes. Do people remain happy, healthy, and thriving when surrounded by large numbers of others?

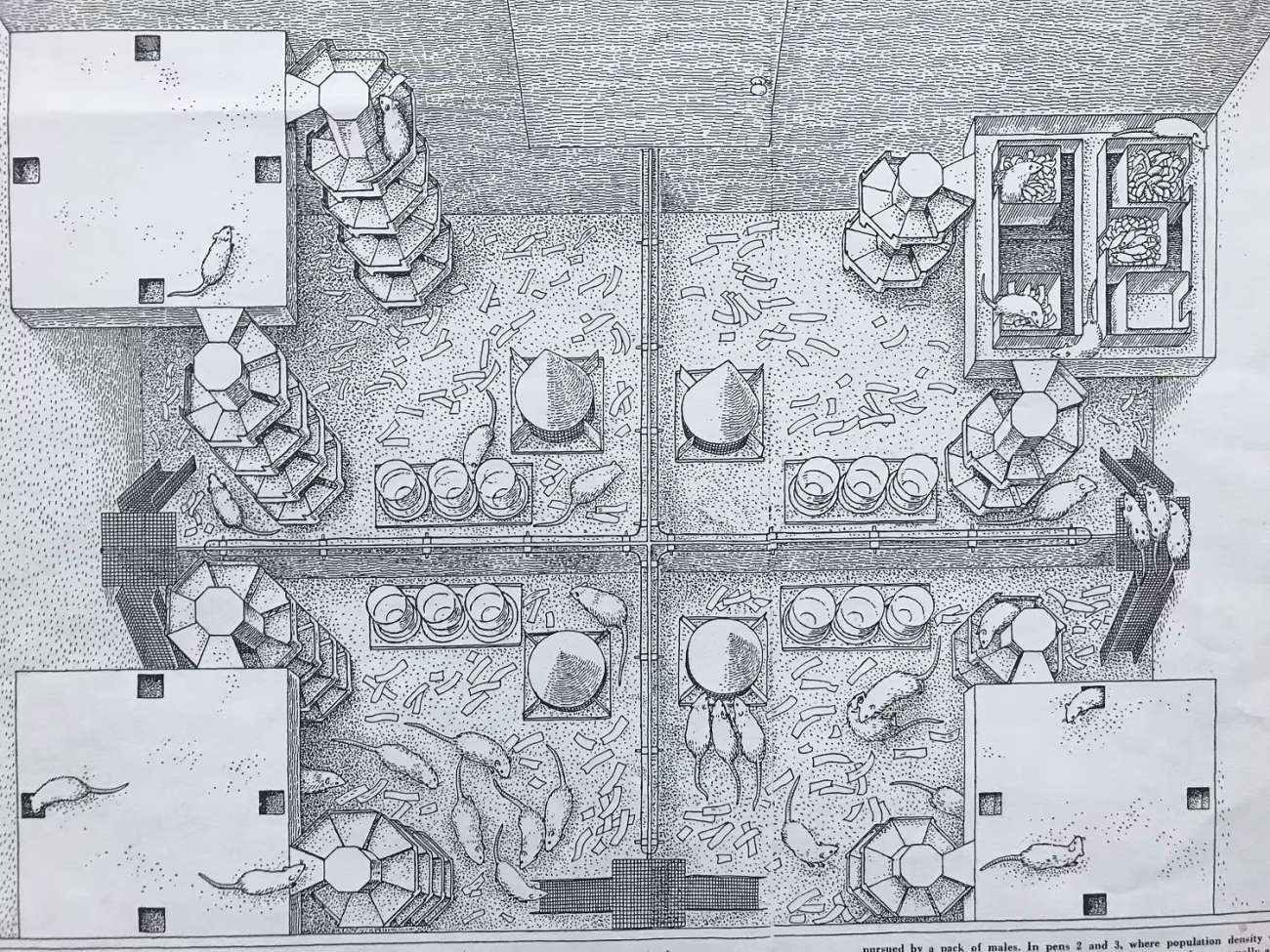

Few studies are able to investigate these questions systematically as it would be extremely unethical to pack hundreds of people into a building and systematically observe how crowding impacted everything from their survival abilities to their social interactions. Therefore, studies have had to focus on other creatures. Most famously, crowding was studied in rats by John Calhoun in what he called his “behavioral sink” studies, but what others have since called the “rat utopia” studies. In this set of studies, Calhoun created a 10 foot x 14 foot enclosure, separated it into four pens, and created ramps so that rats could easily move between the pens, except for pens 1 and 4. Each pen contained a feeder, a water bottle, and an elevated burrow box large enough to comfortably house twelve rats. Four pens with housing for twelve rats each makes the comfortable population capacity of this area 48 rats. He then placed 80 rats into this environment and observed the rat’s behavior. The feeders and water bottles were consistently refilled so that the rats always had enough food and water to maintain life, regardless of how many rats were in the pens. This is why these studies are referred to as “rat utopia” studies. The rats have everything they need to lead full and healthy lives. The only thing that was constrained was physical space.

Across the studies, the rats developed many social issues. The male rats were consistently fighting one another. Some established territories in pens 1 and 4 and guarded those territories fiercely, going so far as to sleep at the bottom of the ramp so that other male rats would not be able to enter the pen the dominant rat had claimed. Female rats stopped building nests while pregnant, had difficulty moving their pups to safe environments, and sometimes abandoned the pups in the pens. Infant mortality in the pens was between 80% and 97%, depending on the study. The rate of female rats dying during birth was also orders of magnitude higher than one would typically see in a natural environment. Other rats chose to avoid their pen-mates as much as possible, waking and moving around only when most of the other rats were asleep. Still other rats (all males) became hypersexual and pansexual, going so far as to chase female rats all around their pens and even into the burrow boxes, which male rats typically never go into. To avoid these hypersexual males, the female rats typically ran into a dominant male’s pen, who would then either fight with the hypersexual male or engage in sexual behavior with him.

Obviously, humans could never be subjected to an experiment like the rat utopia studies. However, humans, like rats, are highly social creatures. Crowding is likely to affect us somehow, even if we don’t know from experiments exactly how we would be affected. There are non-experimental forms of evidence we can use to gain some insight into how humans are impacted by crowding. For instance, if we keep the size of a room constant but add more people to the room, that tends to create negative psychological outcomes for people. There tends to be a jockeying for position and a tendency to defend territory that can result in aggression. This is generally referred to as social density and is often seen in institutions where people are required to be in the space, the requirements for space are always growing, but the locations are not easily expanded. Examples of such places would be public schools, prisons, and in-patient mental health treatment facilities. In all these places, adding people beyond the capacity of the building has shown to have very negative psychological effects on the people occupying that building.

Another type of crowding, spatial density, results from the opposite situation as social density. In spatial density, the number of people remain the same, but people are placed into smaller and smaller locations to increase the density. In these cases, even though the physical density may be the same as in social density, the fact that the people were placed into an entirely new environment with different expectations regarding amount of space and territory available makes people experiencing spatial density far more resilient to the emotional stress caused by high population densities. People can cope with this type of crowding much better and tend to have many fewer problems with aggression, violence, and general stress.

Society

When we start thinking about crowding on a societal level, this is when we begin thinking about words like over-population and concepts like resource use. Thinking about human population and overcrowding at a societal level was most prominently conducted by the British pastor and mathematician Thomas Malthus. Malthus is most widely known for his 1798 essay On the Principle of Populations. This essay makes many well researched and well calculated arguments about populations, the most prominent of which is Malthus’s argument about how populations interact with the food supply.

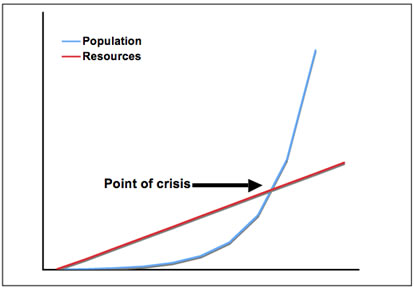

Malthus, Population, and Food

Malthus spent many years modeling the growth of both the human population as he knew it and the ability of that human population to produce food. And from his calculations, he arrived at a surprising and depressing result. He calculated that the population level of any species, with humans being no exception, has the ability to increase geometrically. This means that if you graph it out, the population increase looks like a curved line going up faster and faster and faster as the population grows. This should make sense to us. As more people are born, those people can create even more people. If one person has three children and then each of those children eventually have three children of their own and each of those children have three children of their own, we went from one person in Generation 1 to four total people in Generations 1 and 2 to thirteen people in Generations 1, 2, and 3 and so on. In this way, populations can increase quickly. However, when he compared the possibility of human population growth to how the food supply grows, Malthus encountered a disturbing problem. Using all the available data on grain grown that he had available to him, he observed that the amount of food available to a population can only increase linearly – as in a straight line if graphed out. And the problem occurs when we combine these two graphs. A geometrically increasing population will need a geometrically larger amount of food to sustain itself. But advances in food production did not seem to be moving quickly enough. He predicted that at some point, the human population would no longer be able to produce enough food to sustain itself. When that point was reached, members of the lowest levels of society would be most at risk of starvation as the price of scarce food resources would increase dramatically. He further said that this situation would result in a necessary number of the population dying off to return the population back to a sustainable number.

theory of population.

Malthus in Practice

Malthus’s predictions remained relatively abstract and academic until 1845. This is the year that a potato blight struck Ireland. Potatoes were a staple food crop in Ireland because much of the island’s soil is too rocky to farm grains at a large scale. Potatoes are a very nutrient dense food for the size of farmable land needed, making them an idea crop for Irish farmers. However, in 1845, Irish potato farmers began digging up their crops only to find the edible portions had rotted underground. The potato blight lasted for 8 years and is estimated to have caused 1 million deaths due to starvation and resulted in an additional 2 million people leaving the island and immigrating to other nations – notably a large portion coming to the United States. However, many of the starvation deaths that occurred could have been avoided.

At the time of the potato blight, food was readily available in Ireland. It was simply too expensive for most Irish people to afford. The closest government that can help mitigate the effects of the famine is in England, but many government officials were against directly giving grain to Irish people. However, some were willing to help import American corn into the country to help the starving population ride out the worst parts of the famine. However, Sir Charles Trevelyan, a student of Malthus who was a powerful civil servant within the government advocated against sending American corn to Ireland. He reasoned that sending grain to Ireland would allow the Irish population to become even larger than it already was. Which would simply mean that more food would be needed to feed that larger population. In essence, they feared England would get caught in a loop whereby if they sent food relief to Ireland, then the Irish would make more Irish people, which would require more food to eat which they didn’t have and then England would have to send even more food the next time. Instead, he advocated for the famine to serve as a “natural” check on the population of Ireland.

And though their ideas may have seemed like wisdom when explained this way, I personally find this reasoning to be incredibly cruel. Remember that Ireland was experiencing their lack of food because of an outside force beyond their control. A disease was impacting their usual food crops. Should we have expected that all potatoes forever would be impacted by the blight? English policy advisors at the time like Trevalyan certainly thought the disease would last a very long time. But some potato plants were able to resist the blight. These potatoes became the only ones able to be planted the next year, which increased the proportion of blight resistant potatoes in the population. In addition, potatoes from other areas of the world that were blight resistant were also imported to Ireland to help with this problem. Per capita potato harvests largely returned to pre-famine levels after 8 years, but the damage to Ireland’s population had been done. Millions of people had either starved to death or left Ireland entirely. In fact, so many people were missing or dead that Ireland’s population has not risen above the level it achieved in the 1840s to this day (approx. 8 million in early 1840s compared with approx. 5 million as of 2021). How many people could have been saved from a terrible fate had England simply given excess grain directly to the Irish people in 1847?

Malthus in Modern Times

We now have 225 years of data on how well Malthus’s predictions estimated population levels and food production. We should note two things right away. First, the worst of Malthus’s predictions did not come true. The world’s population continues to increase to this day, yet we do not have widespread famines due to a lack of food production. Second, the reality of population and food production closely matched Malthus’s predictions up until around the 1920s. Throughout the 19th century, advances in medical care, public health, and sanitation lead to ever increasing populations while food scarcities like the Irish Potato Famine and the Famine of 1848 in Europe seemed to increasingly highlight the inability of European farmers to provide food for the population of Europe.

However, the 1920s saw innovations in agriculture that dramatically increased how much food could be grown on an area of land. Some of the most important innovations during this time included the Haber-Bosch process which efficiently converts atmospheric nitrogen into ammonia, which can be used to produce anhydrous ammonia – an effective fertilizer. Other innovations that improved the food supply were mechanized tractors with internal combustion engines, crop rotation, soil conservation techniques, and refrigeration. These innovations together caused a massive increase in the amount of food grown and preserved, which created the conditions to feed a quickly growing population.

One other innovation that also impacted how well Malthus’s model predicted population and food conditions was introduced into the U.S. market in 1960 . That was the introduction of oral contraceptives. Oral contraceptives helped to end the baby boom that occurred after the end of World War II and have also dramatically reduced birth rates around the globe. Populations are now growing much slower than would be predicted by a purely geometric model. In fact, many wealthy industrialized countries are now facing the opposite problem. Their populations are beginning to fall. Notably the populations of China, Japan, Russia, and many other countries in Europe are seeing population reductions – which tend to create labor force problems that often ultimately result in inflation. This is why Hungary is instituting its childcare initiative. They are facing a labor shortage so severe that, by some projections, one out of every four jobs will not have a human in the country to fill it by 2030. This dramatically contrasts with the worst predictions Malthus made regarding populations in 1798. The concerns of the world regarding crowding are much different now than they were in 1798. Technology and innovation have changed the concerns.

Section Summary

Crowding can be considered from many different perspectives, individuals, groups, and societies. Individual crowding is similar to the concept of interpersonal space while group crowding follows concepts of social density and spatial density with social density tending to cause more psychological problems for the members of the group. Societal level crowding was originally modeled by Malthus, but now is governed by other concerns.

Section 3: Territoriality

Hippo Ranchers

In 1910, the United States had reached something of a crisis point. The population of the United States had exploded. Large-scale immigration – from both Europe and China – brought large numbers of people into the country. In addition, improvements in medical health and sanitation which were leading to vastly lower infant and child mortality as well as allowing older people to live longer, more industrious lives. The crisis was occurring because westward expansion had largely ended. Primarily white settlers had established settlements from coast to coast, established railroad networks across the country, and started moving into even more inhospitable environments such as Alaska. To policy makers in Washington, D.C., everything was starting to follow Thomas Malthus’s predictions about increasing populations not being able to grow enough food to feed themselves. When a meat shortage began to impact the country, lawmakers started looking for solutions.

One man with a solution was Robert Broussard, a Congressman from Louisiana. He, along with two individuals – Frederick Russell Burnham and Fritz Duquesne – brought along as “experts” approached Congress with a radical solution to the meat shortage problem. Broussard reasoned that since the United States could not easily obtain more cropland, the solution was instead to raise more food on the land we had. He looked around and found a reasonable large section of land that was not being used to mass produce much food at all: the Mississippi River delta in Louisiana. For all intents and purposes, this land is a swamp. The ground is too wet to raise any grain crops other than rice and too soft and spongy to effectively raise large livestock – their hooved feet tend to sink into the ground causing broken legs. Broussard approached Congress with his radical idea. He would import a large species that could survive in a semi-aquatic environment and ranch them in Louisiana for meat. Specifically, he proposed ranching hippopotamus.

While this idea may sound ridiculous to our ears today, this proposal was taken seriously by a congressional committee tasked with studying the meat shortage problem. This proposal had two things going for it. First was the simple fact that hippopotamus are large creatures with a great deal of meat on them. Average adult hippos weigh around 4,000 pounds with the largest individuals weighing in at more than 6,000 pounds. That’s a lot of meat that can go a long way toward solving a meat shortage. The second issue in favor of importing hippos was that the Louisiana delta was already experiencing problems with another invasive species from South America, the water hyacinth. Water hyacinth are aquatic plants that grow in lakes and rivers. They have long, fibrous stems that extend down to the river bottom. Then, above the water they have large, waxy leaves that form something of a green carpet that can become so thick that birds are able to land and walk on it. And while that may have been fine for birds, the plant stems would become entangled with ship propellers and cause problems for the shipping industry around New Orleans. To Broussard the solution as simple. Introduce a large herbivore to the area, have it eat all the invasive hyacinths, slaughter it, and feed the meat to a nation of people desperate for a protein-rich diet.

Ultimately, the congressional committee rejected the hippo ranching plan. It is probably lucky for us that it did. Because hippos, despite their reputation as very cute and

charismatic megafauna, are incredibly dangerous creatures. On a continent that contains lions, leopards, hyenas, and jackals, it is the hippopotamus that kills more humans than any other African mammal every year. This is because hippopotamus are aggressively territorial animals. If you are in the wild and can see a hippo, it is very likely that the hippo believes you are too close and will use its large size and surprising speed (up to 30 mph under water) to push you away from the area. The problem is that it is a 4,000 pound hippo with sharp tusks and you are a 175 pound human with pierceable skin and squishy insides.

Hippos tend to be territorial for fairly simple reasons. Their natural habitat tends to undergo extreme shifts in rainfall. There will be extensive rains followed by long periods of drought. For a species that needs water to survive, drought is particularly deadly. In fact, drought is the only effective method of reducing the population of hippos in their native habitat. Therefore, hippos tend to aggressively defend any patch of water they choose to call their own. But now imagine an invasive population of hippos – which would remain territorial in their new environments – running around the delta in Louisiana. It never gets dry in that environment. There would be nothing that would check the population of hippos, there are no predators big enough to eat them, the environmental conditions wouldn’t stop them, even hunting them is difficult with their very thick hides. A very dangerous situation could result if any hippo were to take up residence in a recreational lake or river. Damage to both people and property would be very likely.

Territoriality in Animals

Territoriality in hippos, and in many other animals, is often about protecting resources that are needed for survival. This may mean different things for different animals. Some animals defend areas where they can easily access their preferred foods, some – like the hippo – defend areas of water, and some species – like the stickleback fish – only defend territory from objects with the general shape and color of another male stickleback fish because they want to defend the access to reproduction that the place provides. But the general theme is usually the same. Defending a place because of access to something important that the animal feels it needs for survival.

Territoriality in Humans

Humans, of course, add additional complications to this issue. Our ability to think and reason abstractly allow us to be perfectly fine with certain humans entering our territories for reasons we understand due to context. For example, I don’t get upset with the worker who casually walks into my back yard to read my electrical meter. My dog has a massive problem with it, but I don’t. However, this ability to understand context also generates additional complications.

When we consider humans, we can generally think of three different types of territory. Each type allows different interactions, has different feelings of “ownership” attached, and is protected or defended differently.

Primary Territory. Primary territory is a territory that is considered very important to someone. It may be used as a primary residence or sleeping place. The most critical parts of this type of territory are that 1) the person intends to return to this territory repeatedly over the course of at least several days (if not weeks, months, or years) and 2) even when the person is not currently occupying the territory there is an expectation that no one except those with prior approval will be in the territory.

Primary territory also brings out the most feelings of “ownership”. In some cases, the people occupying the primary territory have gone through the legal system to obtain legitimacy for occupying that territory. They have signed an hours’ worth of paperwork to buy a house. Or they have signed a contract with a landlord to rent a space for a prolonged period. However, not all primary territory is granted the legitimacy of the legal system, but it can still be defended in extreme ways. Some individuals utilize cars, storage sheds, or even spaces in the grass as primary territories. And even though they know that their continued existence in that territory would not have the backing of the legal system, they are still likely to defend that territory in whatever way they can. The primary territory is a critical piece to the way they are living their life. A change or loss of that territory would be highly disruptive to their lives.

Primary territory is the most defended type of territory. Large parts of human psychology and the legal system are centered around the security of primary territory. If someone were to enter your home, apartment, or dorm room without your knowledge or permission, this would likely be very upsetting to you. In the most extreme cases we call this the crime of home invasion and experiencing it is highly correlated with being diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder. Therefore, protecting primary territory with locks, passcodes, security key cards, fences, gates, or other means of defense is incredibly common. Some states in the United States have even passed laws saying that property owners are within their rights to use deadly force if they feel threatened by someone invading their primary territory.

Primary territory is critical to someone’s current way of living. And therefore, it is the most thought about type of territory and the most defended. Primary territory is the closest that modern humans get to a hippo’s feelings about its water source. But primary territory is not the only kind of territory we think about or want to defend.

Secondary Territory. Many college students have “their seat” in a class. Usually that seat is the seat they sat in on the first or second day of class and then continued to return to day after day. Studies have shown that approximately 70% of college students will sit in the same seat for an entire semester. But most college students have also experienced walking into class – often on an exam day – to find someone they’ve never seen before sitting in their seat. If you have experienced this, you have experienced an invasion of your secondary territory. Secondary territory has some elements in common with primary territory, but it is less critical to our survival and continued daily routines. We define secondary territories as territories that someone expects to return to and engage in repeated use of, but that are not critical to survival like primary territories. You likely do not have a key for any secondary territories that you have and once you leave that territory, someone else is free to take over that territory – as long as they know you have left for a long time and don’t plan on coming back. We might always expect to find that particular seat in the classroom open at 11:00 A.M. on a Wednesday, but once the class is over we are perfectly fine letting others use that same seat for different classes. In fact, I have observed some college students having back-to-back classes in the same room but moving seats for the second class.

Unlike primary territory, secondary territory has fewer options of response to invasion. Note that we are using the word “invasion” entirely from the perspective of the person that was expecting to use this territory at this particular time. The person currently occupying the territory may have no idea they are being thought of as “invading” the space by someone else. They may just be thinking they need a place to sit down to take the exam. You did not sign a contract to be given exclusive access to that seat during your class, or your favorite study spot in the student union, or the most comfortable chair in the coffee shop. Because of that, feelings of ownership over the space tend to be reduced. We tend to feel less comfortable personalizing a secondary territory, especially with markings that cannot be removed. And while we may feel frustrated or upset when we find someone sitting in “our spot”, that person being there does not typically trigger a psychological reaction that could require years of therapy sessions like an invasion of primary territory can.

Similarly, the options for defending a secondary territory are also reduced. The most common method of defending a primary territory is by marking. This means placing objects or other indicators that the place is currently being used. Perhaps you want to make sure that your classroom seat will not be taken on exam day, so you arrive earlier than usual to make sure you get it. But then, you also need to use the restroom. You could mark your place by leave something of yours at the chair; perhaps a coat, a backpack, or a laptop if you are particularly trusting of your fellow classmates. Markings in territories are almost always respected. In fact, field studies have shown that leaving a single sweater in a booth at a busy sit-yourself restaurant can defend that booth for up to an hour.

Another common method of defending secondary territories involves the spreading of norms within the community of users. Say there is one computer at your workplace that you like using over all the other ones. We’ll imagine you like using it because it has a fun desktop background that the other computers just can’t compete with. You could let your co-workers know that you really like the fun-background computer and would really appreciate using it when you are working. If your co-workers accept this, you have just established a norm within your community and likely established a level of control over this secondary territory at your workplace.

Tertiary Territory. Finally, we have tertiary territory, which is a concept that is a bit difficult to pin down. Most territory theorists agree that there is a level of territory below secondary territory that people treat differently than secondary territories. However, the line between secondary and tertiary territory is much more muddled compared to the line between primary and secondary territories.

Tertiary territories are often thought of as the territory of “right now”. You don’t intend to return to this space, nor do you have any beliefs that if you lose this territory that you will be able to get it back. But for the moment, right here, right now, this space is the space I’m using, and you can’t move me from it. Imagine setting up a picnic spot in a public park. You spread out your blanket, maybe set up a sun umbrella, and for the time that you are there, that is your picnic spot. Nobody is going to come along saying that this is their usual picnic spot and you need to move 20 feet away (well, somebody might say that, but you aren’t going to feel obligated to listen to them).

Tertiary territories therefore lack both critical elements of primary territories. The person occupying the territory is likely not expecting to return repeatedly to this spot over any reasonable length of time and once they leave, they are expecting that others may come in and immediately use that space.

Defending a tertiary territory can also be difficult. Anyone that has tried to save seats at a general admission event knows this. You may place a coat or other marker down, but those markers can be quickly ignored, especially if a person isn’t there to let people know about the “saved seats”. However, some defense is possible with a combination of markers and physical presence by a person.

Qualified Users

What tends to keep most people out of secondary and tertiary territories is actually a sense of community norms. People that frequently use a space can come to believe that only a certain kind of person uses this space. That sort of person is termed a qualified user and will typically be allowed into the space without notice. However, if someone enters the space and is not deemed a qualified user, the community within that space can quickly turn hostile towards the person entering. I have been at target shooting ranges where a woman walking in to participate is viewed as so strange and out of the ordinary that the woman is repeatedly asked inane questions and stared at until she leaves. I have also been to Country Clubs where anyone wearing t-shirts and jean shorts rather than a polo shirt and khakis are viewed as lesser people that should not be using the golf course. Similarly, I have never set foot in the biker bar in my home time. Those people would immediately clock that my suit jacket with the leather elbow patches had no business being in that place and would likely make it very clear to me that I am not welcome there.

Perceptions of qualified users tend to be established by visual cues that are easily distinguished. This also means that people tend to use frequently stereotyped characteristics – gender, race, ethnicity, social class signals – to determine who “belongs” in the space and who does not. This can be expressed in phrases like “X while Black”, where X is any normal, innocuous activity like driving, shoveling snow, or walking that a black person engages in and gets hassled by either community members or the police. White individuals would not be looked at twice for doing the activity, but black individuals are looked at several times over. This phrase is expressing frustration about not being viewed as a qualified user of a space because of race. There are many other spaces where someone must be of a specific gender, or wear a certain attire, or signal a certain amount of wealth to be deemed a qualified user. I should note that by pointing this out, I am not saying that any of this is good, ideal, or something that should be accepted. Perceptions of qualified users are norms, not laws. We all have the power to change our ideas about who belongs in the spaces we inhabit. We simply must acknowledge the reality that some community norms are hostile towards certain people and those people must react to the norms they experience rather than what is just.

Section Summary

Humans are somewhat territorial creatures that have different ideas about territory depending on how often they expect to return and whether they believe someone else will be using a territory while they are gone. Primary territories are the most central territories to people’s lives, followed by secondary territories, and finally tertiary territories. Entry into secondary and tertiary territories tends to be governed by norms around Qualified Users that exist within a community.

Section 4: Privacy

Tracking Military Activity

In January 2018, Nathan Ruser, a 20-year-old student in Australia studying International Security heard about a map posted online from a running blog he frequented. This map was created by a social media company called Strava, which was designed to connect people around a love of running. On Strava, you could connect your Fitbit or other workout trackers and save information about your workout routine – miles ran, environmental conditions, and location. The location tracking is most important for this story. On Strava, location tracking was turned on by default. It was possible to turn it off but required each individual user to navigate two to three layers into a menu to actually find the option to turn it off.

Nathan Ruser checked out the map and thought it was interesting. You could see some areas that were extremely bright, like in Europe and coastal United States indicating a lot of people using the fitness tracking devices and the social network. At this point Nathan, being an International Security student, wondered about areas of global tension and war. He began looking at Syria, a country experiencing a great deal of conflict and turmoil at the time. He noticed limited activity, but the activity that was there was confined to relatively small areas and was highly concentrated. Using knowledge and sources gained from his studies in International Security, he began piecing together that many of these areas of concentrated activity were military installations. He could see the outline of the US Special Forces base in Kandahar, Afghanistan. He could see the outlines of known or suspected military intelligence bases in Syria and Yemen in the Middle East, and Niger and Djibouti in Africa.

The tracings indicated huge amounts of information about the workings of the US and other country’s military operations in these areas. Some branches of the US Military had handed out devices like Fitbits to help soldiers track their workouts and physical activity to monitor fitness goals. Now, through this map published by Strava, they showed the outlines of bases, as many soldiers would jog along the outer perimeter of the base to get the longest workout possible in the space they had available. The map also showed typical routes used to enter and exit the facility, roads that were traveled on to get there, and brighter areas inside the facility that were likely living quarters. An enemy armed with this information could gain a tactical advantage should they want to attack this location. They would know where to ambush supply lines, where people might be caught unaware or relaxing, and where gaps in the patrol route might exist.

So, of course, our 20-year-old International Security student did what many young people do in modern times. He posted his findings on social media – in this case Twitter. Very quickly, a portion of Twitter interested in International Security began crowdsourcing the map uncovering potential secret intelligence bases, Patriot missile sites, and military installations still under construction.

Privacy is usually heavily guarded by military institutions. Information about soldiers’ locations, armaments, capabilities, and specializations can change the course of a battle. Keeping such information hidden can be of vital importance to those engaged in combat. Yet here we see high-ranking members of the US military giving their soldiers a device with the capability to reveal all this information and more and not providing the training needed to shut off the collection of that information. Furthermore, we see a single student in Australia connecting with others through a different social media site to crowdsource what the map means and what information could be obtained from it.

Our modern world asks us to think deeply about what privacy means in modern times. Do we still expect privacy to work the same way it worked before everyone carried smartphones connected to a vast, global information network accessible at nearly all times? Do we apply our notions about physical privacy to the digital world? Do we expect privacy in a digital space to work the same way as closing a fence or door works in the physical space? Do the calculations of “the algorithm” count as social interaction and can we control those calculations the same way we control our social spaces?

Privacy Definitions

As a term, privacy has a problem. It is a common word used by many different people, all with slightly different contexts and perspectives about why they are using the term and what they want to use it for. This is even true for academics as there are two different definitions of privacy that are used in privacy research. Social scientist Irwin Altman defines privacy as “…the selected control of access to oneself or to one’s groups…”. This is typically the definition that is used by social scientists undertaking research into privacy. And because the definition is used by scientists that study social interaction, this definition focuses on the ability to physically remove oneself from people and to control one’s ability to interact with others. However, privacy is an important topic in other fields as well, particularly the law. The legal concept of privacy is used the world over as a philosophical building block undergirding human rights. Legal privacy advocates often argue that basic human rights like freedom of assembly, press, and speech require an element of privacy. Westin, in an essay theorizing about the importance of privacy for people to live in a society of laws, defines privacy as “…the claim of individuals, groups, or institutions to determine for themselves when, how, and to what extent information about them is communicated to others”. Notice how this definition focuses more on controlling information about the person rather than physical interaction. This distinction was largely academic when both definitions were developed in the 1970s as at that time physical interaction and information sharing largely occurred in the same spaces. However, in modern times, this distinction has taken on new meaning with the creation of the internet, where information can be shared without any physical social interaction at all.

Physical Privacy

Perhaps more than having a fully formed, concrete definition of privacy, we need to understand what privacy does for people. It is important to remember that the theorizing about privacy from both Westin and Altman was done in the 1960s and 70s – a time when privacy was much more about physical, face-to-face interactions than it is today.

When we think about what physical privacy does for us, we can recognize that most animals, including humans, will seek solitude or very small group social settings from time to time. In animals, these events often correspond to birth and death, but even creatures known to gather in herds choose to be alone from time to time. In animals, this desire to be alone seems to be highly adaptive. For instance, when rats are given spaces in which they can attain some measure of solitude, even if that space is only eight inches square, they seem to thrive just as well as when they have a quarter-acre of open space. Privacy seems to trigger a calming state – reducing aggression and stress responses and increasing long-term adaptive behaviors like nest building.

This is also true for highly social species such as humans. When humans think about privacy, we may think about the physical privacy that animals seek. Generally, humans do this around biological functions such as urinating, defecating, or lovemaking. Humans also have a general desire to be alone from time to time, just as many social species do. However, this is not the only way humans think about privacy. Before the internet, physical presence and information sharing went hand-in-hand. When people would gather together, they would naturally share information about themselves. When sharing information about themselves, people would be in control of what information is shared and what information is not shared. This information sharing could then be reciprocated by a conversation partner in a process called mutual disclosure. Mutual disclosure is an important element in friendship building. It is a way to build trust in burgeoning friendships.

In some cases, however, people will share information about others. Some might call this gossip. Others would call this letting good friends know about the community. Regardless, through a process of engaging in a behavior, observing the consequences, and discussing those consequences with others, we develop norms about privacy. Each society enters into conversation and constant revision about what information is appropriate to share about others and what is not. In some cultures and contexts, private information can be freely shared within the family unit but not outside it. In others, one can expect that anything shared anywhere will be known to all soon enough.

Finally, privacy can function as an important element of large-scale organization. There are many pieces of information that organizations wish to keep hidden from one another, usually because the organizations are opposed to one another and each fears a tactical imbalance if the other party were to know about plans and strategies being implemented. Military strategy is a good example of this and ties back into our original story. The problem in our original story is not so much our Australian student utilizing a social-media network to report on military installations. The problem is that this information exists at all and could be used by an enemy force to ambush supply shipments, devise attack plans against more poorly defended areas, or simply alert them that an otherwise unknown force is present in the area. These same ideas apply to the business world in which companies are often attempting to outmaneuver one another to achieve greater profits. In both cases, how and with whom information is shared is of critical importance for predicting the success or failure of an operation.

Information Privacy

When Irwin Altman was writing his collected thoughts on privacy in the 1970’s, the experience of privacy was much different than it is today. In the 70’s, privacy meant a physical distancing from other people; a way to remove oneself from a situation and gain refuge from the world around. Today’s world does not afford us many of the same luxuries regarding privacy as then. The ubiquity of smartphones, wearable trackers, and the internet have converged to create a bomb of privacy concerns. Most of us experience our lives with a belief that we have a great deal of privacy. However, every now and again one of our privacy bombs goes off. And when that happens, we understand very quickly how little privacy we have in modern times.

Consider the situation at the beginning of this chapter. The amount of military intelligence that was simply given away to the internet staggers the mind in that case. People’s lives were likely put in danger, for who knows how long. Yet, from a civilian policy standpoint, nothing was done on a wide scale to ensure the same problems would not befall others. Certainly, military policy was adjusted to disallow fitness trackers on Army installations but nothing systematic was extended to the population at large, at least in the United States.

Earlier in the chapter, I introduced Westin as another thinker who applied ideas of privacy to the world. Westin was more interested in the application of privacy to matters of law. He argued that privacy is much more about information sharing that it is about physical presence. According to Westin, a social species like humans getting together isn’t interesting. Instead, it was the information they shared with one another when they got together that was the critical element.

Westin argued that information privacy has four primary functions for human behavior: 1) protected communication, 2) a sense of control, 3) identity development, and 4) emotional release.

Protected Communication: Some communication needs to be, in legal language, privileged for both professional and social reasons. The law provides many protections for people whose job requires them to keep certain communications confidential such as lawyers and counselors. Without that confidentiality, someone may find it difficult to express themselves freely enough to heal from trauma with a counselor or explain a situation so a lawyer can provide a best defense. Privileged communication is also important for the building of social relationships, both to signal to the potential friend that they have an elevated role in someone’s life and as a way for the potential friend to demonstrate that they have the best interests of the person at heart.

Sense of Control: Private spaces are places where people can exert their maximum influence over the space. Without that privacy, someone may be concerned that they must consider the opinions and desires of others in the space, which necessarily reduces the amount of control that the person has. Sense of control has been shown to have a profound impact on people’s general well-being. In a famous study of elderly individuals institutionalized in nursing homes, residents that had control over small elements of their lives, like whether or not they would water a plant or which of two scheduled movies they would attend showed markedly better health outcomes, up to and including longer lifespans compared to residents that were told which movie they would be watching and had the staff water their plant for them.

Identity Development: Westin argued that social situations demand a lot of our cognitive resources. It takes a lot of thinking power to be social. When we are around others, we can spend a lot of attention focusing on them, their reactions, and their needs/desires. However, private spaces allow us the space and additional cognitive resources to reflect on situations and circumstances experienced throughout the day. This helps us to integrate those experience into a coherent, whole person. When attempting to figure out who the “real me” is, very often people will retreat from a situation and seek solitude.

Emotional Release: Many cultures have norms that discourage the release of emotion in public, except in very rare circumstances. Privacy can give people space to express those emotions in a culturally appropriate way that does not feel to the person expressing those emotions that they are losing face with their community.

So how can we apply Westin’s typology to privacy in the digital age? Protected communication has been a place where people often have expectations of privacy, only to be let down by how digital technology works. People may believe they are expressing themselves to a smaller circle of friends and family when their communications on social media may be broadcast to the entire platform by default. And, much like in our military story in the beginning, the ability to turn on protected communication may be very difficult to do for someone not fully immersed in technology. Sense of control may be similarly impacted. Account holders may be expecting that personal information that they have given to the platform is not being used for any purposes that they do not consent to. However, very often, digital media companies are explicitly using information that they know about their users to sell targeted advertising to you and your social network. Indeed, Charles Duhigg recounts a story in his book The Power of Habit in which a retail corporation used information about people’s shopping habits to make predictions about whether or not the person was pregnant. If correct, such predictions can be highly lucrative as the retail store can send coupons for baby related items and get shoppers into the habit of coming into that store for their baby needs. However, not everyone wants to know that their local retail store has knowledge about their body and medical situations, even if that knowledge was an educated guess. Knowing what your local retailer knows about you can be a blow to your sense of control.

So far, our first two elements of privacy show largely misplaced expectations and mishandled hopes of privacy from digital media companies. However, our third and fourth elements, identity development and emotional release, can be argued are afforded too much space on the internet. In terms of identity development, one can find any community one could possibly ever want on the internet. In some cases, this is very helpful for members of marginalized communities to come together and discuss how to help one another in solidarity. However, these same structures can be utilized by people seeking to marginalize others in exactly the same way. Digital spaces can be used to help people express and integrate elements of their sexuality or gender expression just as easily as they can be used by other people to plan and justify violence against another race or social group. How to regulate identity development online is currently an open debate that underlies several current political and social arguments.

Similarly, how to regulate emotional release online is another open question that generates mountains of arguments from many different parties. In a general sense, people interacting in a digital space may feel enough anonymity to express extreme and socially inappropriate emotions in large social spaces. This is well expressed by the web-comic Penny Arcade’s “Green Blackboards (And Other Anomolies)” in which a normal person granted anonymity and an audience cannot help but turn into a curse-spewing monstrosity. However, in other contexts, people may feel that the limited human contact generated through text messages or instant messaging apps provides the safety needed to express emotions that they would not otherwise feel comfortable expressing. Once again, much more thought and effort must be placed into our understanding of regulating this element of privacy in digital spaces.

The European Union has extended privacy laws to be more in line with the concerns of the digital age. In 2018 the European Union passed the General Data Protection Regulation, more commonly known as the GDPR. This large body of legislation applied to any personally identifiable data that was collected about any European Union citizen by any entity on Earth. It doesn’t matter where in the world the data is sent to, if it is about an EU citizen, the company collecting that data must abide by the policies contained in the act. These are things like keeping a log of all the data a company has about a person, making that log available upon request of the person the records pertain to, and ensuring that a person can be “forgotten” – meaning their data can be deleted upon request. And while this is a European Union law that only truly applies to European Union citizens, the global nature of many tech companies means that, even if you are not an EU citizen, you may be able to request and receive this information yourself. If you do, you may be surprised at the amount of information large tech companies have that applies to you.

But there are other open questions about how privacy will connect with new digital technologies. Police departments are already running DNA samples through ancestry databases attempting to find familial matches to narrow down potential suspects. Several high-profile cases have identified suspects in this manner, including Bryan Kohberger who pleaded guilty to the murder of four University of Idaho college students in Moscow, Idaho in 2022. Uber drivers in Texas have shown a propensity for denying rides to women they suspect may be attempting to get an abortion. Texas law makes aiding someone in an abortion a felony and Uber drivers know that their phones are constantly sending location information to Uber. And spouse murderers have been apprehended when their wearable step-tracker indicated that their alibi could not possibly be true. How we will deal with all these privacy concerns will be a defining element of the coming years. Even though we cannot exactly predict how digital technology will interact with privacy in specific ways, we can know something about how people will expect privacy to be upheld when the concept is transferred to digital spaces. The question is whether or not these expectations match the reality of the situation.

Section Summary

Theorizing about privacy comes from two distinct areas. Altman’s depiction of privacy as control of social interactions and Westin’s approach that focuses on information sharing. Privacy provides useful functions for people including protected communication, sense of control, identity development, and emotional expression. Modern digital technology is a minefield of privacy concerns that our norms, policies, and laws are just barely beginning to grapple with.

The study of human use of space and how space impacts behavior, communication, and social interaction.

The distance people maintain between themselves and others during social interactions.

The amount of space we give to close friends

The amount of space we give to our closest relationships. Generally, only intimate partners, close family, and pets are allowed within intimate space.

Space for anyone we are engaged with in a back-and-forth interaction. We may not know the people we engage with very well, but we are open to conversations with these people. Many business interactions are conducted in social space.

Space for anyone in the general public. Public speakers talking to a general audience tend to use this level.

Cultures in which the zones of interpersonal space tend to be smaller and closer together

Culture in which the zones of interpersonal space tend to be larger and more spread out

Also called the "rat utopia" studies, a series of studies in which John Calhoun gave rats enough resources to live, but over crowded them to the point they developed abnormal social behavior.

When density and crowding are increased in a space by keeping the size of a room constant and adding more people.

When density and crowding are increased in a space by keeping the number of people in a space constant and reducing the size of the space.

An economic situation in which prices are rising faster than wages. Results in people feeling as though items are more expensive and being less able to purchase goods and services.

Behavior related to the perceived, attempted, or actual ownership or control of a definable physical space, object, or idea

A space that an individual or group owns and uses. The owner feels they have complete control over access and use of the space, and others recognize it as private.

A space that can be claimed temporarily, but is neither central to a person's life nor exclusively owned. The person using it expects to be able to return to the space and use it semi-periodically.

Territory of “right now”. One doesn’t intend to return to this space, nor has any beliefs that if one loses control of this territory that they will be able to get it back.

A person deemed acceptable to be in a particular space by the other people that typically use that space.