11 Climate Change

An Island Nation is Slowly Going Underwater

In November of 2021, the United Nations held their 26th “Conference of the Parties” meeting on climate change in Glasgow, Scotland – known informally as COP26. This conference was an opportunity for world leaders to come together to discuss the impact of climate change across the globe. The conference included world leaders, scientists, human rights advocates, industry leaders, and activists of all stripes. Attendees did the typical conference things like listening to speakers, eating catered food, and connecting with people around the themes of the conference. One speaker, though, was particularly memorable. This was foreign minister Simon Kofe speaking for Tuvalu, a small island nation in the southern Pacific Ocean. Mr. Kofe recorded his message for the conference dressed in full suit and tie, standing at a lectern with the flags of Tuvalu and the United Nations behind him. He was also standing knee deep in the Pacific Ocean. His message was a powerful one. Where he stood had been the coast of Tuvalu 30 years ago. But now, increasing global temperatures were causing the polar ice caps to melt, releasing trillions of gallons of water into the oceans. Ultimately, this means oceans rising by a foot to a foot and a half. This may not seem like much, but when your small island nation only averages 10-15 feet above sea level, it can mean a dramatic difference in where your coastline is, how much land you have available to grow food, and where people can build their homes.

Ultimately, Mr. Kofe spoke to the COP26 conference to address an existential question that has been circulating among most of the nations in the Pacific whose land is low-lying reef islands. If climate change continues, ocean levels continue to rise, and sovereign island nations that are current members of the United Nations like Tuvalu go underwater, will the United Nations still consider them a country? The World Bank has already issued reports that the Marshall Islands could lose nation status with their organization if ocean levels rise another 3 feet. In that case, projections indicate that 40% of Majuro, the capitol city, would be flooded and one of the atolls that make up the country would be completely under water. Low lying reef island nations like Tuvalu and the Marshall Islands represent the places in the world most dramatically impacted by climate change currently. It is difficult to think of an impact greater than your entire country being swallowed by the ocean. But this is not the only way that climate change has impacted and will continue to impact humans as we move through the 21st century and beyond.

The Greenhouse Effect

Before we get too far into understanding the impact of climate change on humans, it may be helpful to do a quick review of what the problem is. This is intended as a short, broad strokes review and may gloss over some important details of the problem. But being on the same page regarding the general issue can be useful.

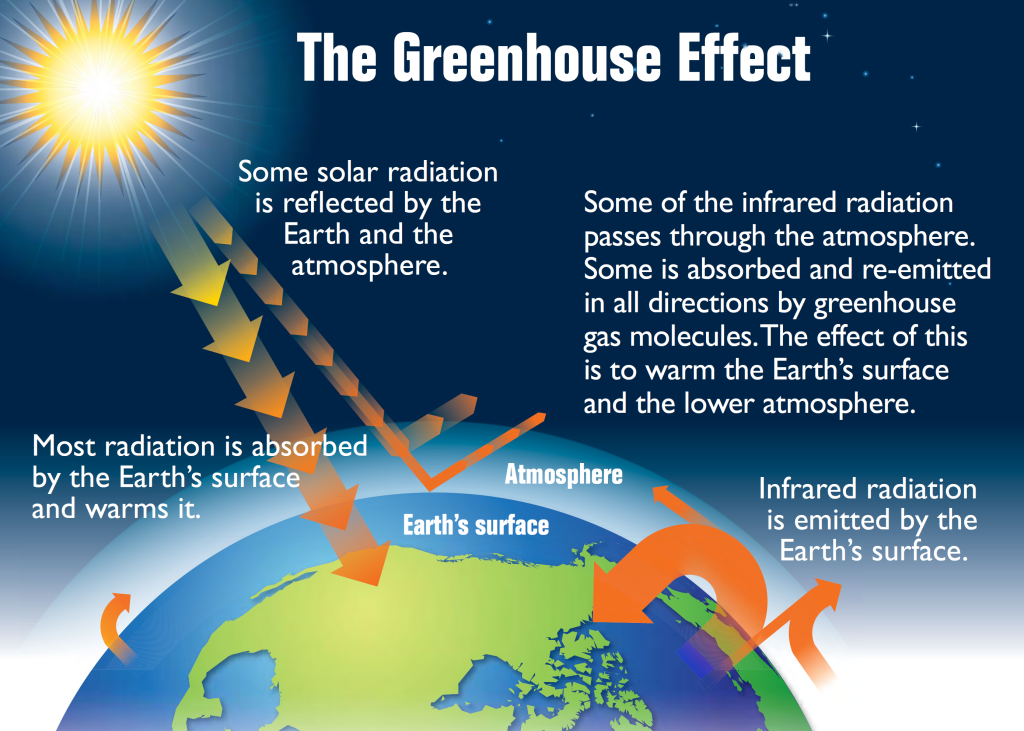

Energy from the sun is transmitted to Earth through radiation. There are many different forms of radiation, from radio waves which can transmit information across vast distances, to infrared which warms us, to the narrow band of visible light we interpret as color, to ultraviolet light which gives us sunburns, to x-rays which can be used to see through soft tissue, to gamma rays which created the Incredible Hulk 😉 are all part of the radiation we receive from the sun. Thankfully, Earth’s atmosphere and magnetic field help filter out some of the most dangerous forms of radiation and allow life to flourish. But this brings up an interesting point. Certain molecules in the atmosphere are opaque to some forms of radiation, but not others. When it comes to carbon dioxide, this molecule is transparent to visible light. Visible light will pass right through it and, as such, our brains will not register that it is there. It’s just part of the air to us. However, carbon dioxide is opaque to infrared radiation – the type of radiation that brings heat. If infrared radiation hits a carbon dioxide molecule, it will bounce off it, returning to where it came from.

Inside the Earth’s atmosphere, infrared radiation bouncing off carbon dioxide molecules creates a situation much like a greenhouse. Indeed, this effect is called the greenhouse effect. Infrared energy transmitted from the sun travels to the atmosphere. Some of it hits carbon dioxide molecules and bounces away into space. But a good amount of it avoids carbon dioxide molecules and travels through the atmosphere and impacts the Earth. Here it bounces off clouds, the ocean, or the ground and starts to head back out into space. However, the more carbon dioxide (and other molecules that are opaque to infrared) in the atmosphere, the more likely that those infrared rays that bounced off the Earth will not make it all the way back out into space. Instead, they bounce off carbon dioxide molecules and return to Earth again, retaining that heat on the planet instead of radiating it back out into space. The general problem with climate change is that our atmosphere is accumulating additional energy.

What makes this additional energy a problem is what the physics of the atmosphere tends to do with it. Increasing heat is one place this energy goes, but the temperature does not rise in all places equally. Temperatures at the poles tend to increase more than temperatures around the equator. In addition, more energy in the atmosphere means higher wind speeds, particularly in severe weather events like hurricanes and tornadoes. In some places, the increased energy might mean additional rainfall, flooding, and higher heat indexes due to increased humidity. In other places, it could mean that high pressure begins to dominate and no rain falls at all leading to exceptionally long droughts. In total, the effects of climate change are uneven across the globe. Some locations might barely notice the changes while other places see dramatic impacts up to and including an island homeland no longer existing.

Human Behavior and Climate Change

When discussing climate change is useful to return to the idea of transactions in Environmental Psychology. In fact, climate change is one of the main places that we see transactions play out. Humans are a large driver of climate change, largely through the burning of fossil fuels. Humans have changed the environmental system through our use of technology in this way. However, now that the environmental system has changed, there are many cascading impacts that occur. Sea level rise is one example. Even on the continents, major cities such as Miami, Florida need to respond to rising ocean levels or risk losing large sections of habitable land to the ocean. And how people and places respond is our first important distinction inside this transaction.

Environmental Psychologists tend to make a distinction in peoples’ responses to climate change. This distinction is somewhat arbitrary, but it does help separate different types of behavior that have different purposes. Just be aware that there is no hard and fast line between these two types of behavior. We can think of people responding to climate change by either coping – which Environmental Psychologists use to mean short-term strategies designed to avoid the symptoms of the problem – or adapting – which Environmental Psychologists use to mean long-term strategies designed to actively deal with the causes of the problem. If you are familiar with the terminology of clinical psychology, coping in this book refers to something like emotion-focused coping and adapting refers to something like problem-focused coping. In the case of sea-level rise, an example of coping would be the efforts by the state of North Carolina to pick up and move a historic lighthouse away from an eroding coastline by several thousand feet.

We would call this coping because the problem continues to occur and, frankly, to get worse. Moving the lighthouse doesn’t change the reality of sea level rise. If nothing else changes, in thirty years the moved lighthouse will again be facing an encroaching sea threatening to swallow up the land it is built upon. But moving the lighthouse does ensure that it will not fall into the ocean in the next year. Adapting, on the other hand, would involve active efforts to stop the problem or permanently ensure that the problem cannot impact humans. An example of is the city of Miami building massive concrete seawalls to ensure that rising sea levels do not encroach on lands homes are already built on. The ultimate adapting would, of course, be to move away from a dependence on fossil fuels for energy but that reality is still several years away.

Moving Toward Climate Action

Many people in the United States are making conscious efforts toward emitting less carbon dioxide. The United States peaked in total carbon emissions entering the atmosphere in 2005 and has been declining ever since. The decline can be attributed to many different factors including increased fuel efficiency standards for transportation, increasing production of wind and solar electricity, decreasing production of electricity produced by burning coal, and increased energy efficiency standards for household lights and appliances. This was a trend already moving in the right direction before the summer of 2022 when the United States Congress passed the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA). The IRA was a massive 2 trillion dollar piece of legislation that addressed many overlapping problems impacting American life. And one of those problems that saw a portion of the funding granted was the impact of climate change.

Inflation Reduction Act. The portions of the Inflation Reduction Act that directly address climate change represent the single largest source of funding to directly reduce climate change ever passed by a democratic country. The total package is estimated to cost approximately 350 billion dollars and reduce the United States’ carbon footprint by 40% by 2030. Like most federal legislation, this portion of the IRA has hundreds of small programs and provisions that add up to the very large price tag. However, we can think of the act having three general goals.

Goal 1 – Reduce the amount of carbon dioxide that is emitted into the atmosphere. Given that we understand the problem of climate change, we can understand why it would be important to reduce carbon dioxide in the atmosphere. To that end, many of the programs that seek to satisfy this goal are directly tied to electricity production that does not require the burning of fossil fuels like solar, wind, and nuclear. Money is available to utilities to defray costs associated with building solar panels, wind turbines, and battery storage units. Battery storage units provide what is called firm power, which refers to power delivered when the sun isn’t shining or the wind isn’t blowing. Money is also available to improve existing nuclear power plants to provide additional firm power. Federal grants and loans are also available to utilities to improve electricity transmission lines, install carbon capture technology in fossil fuel burning electrical plants, and for rural co-ops to install renewable energy production facilities. More grants and loans are available to cities to purchase electric versions of garbage trucks and city busses. In addition, the postal service will be switching entirely to a fleet of electric vehicles.

Note how most of the money in this goal is targeted toward larger organizations like utility companies, power co-operatives, city governments, and the US Postal Service. However, that doesn’t mean that the legislation is entirely geared toward these larger organizations. There are many tax credits geared toward individuals as incentives to switch to electric appliances and vehicles rather than their fossil fuel burning counterparts. This leads us to Goal 2.

Goal 2 – Lower the cost of electrification on individuals. The program creates tax credits for homeowners who replace fossil fuel burning furnaces and water heaters with electric versions. There are also tax credits for home energy efficiency improvements like improving insulation in northern climates. There are also credits for purchasing electric vehicles, though these credits are either already used or held up until 2024 or 2025. The electric vehicle credits are only available for vehicles manufactured in the United States. Currently, there is very little capacity to manufacture electric vehicles in the United States, however more capacity should become available soon. There are also current court cases working out exactly what it means for a vehicle to be manufactured in the United States. Do parts need to be manufactured in the United States or can the vehicle be simply assembled in the United States from parts manufactured elsewhere? These credits are provided because the upfront costs associated with moving away from fossil fuel burning appliances and vehicles can be quite high. These incentives provide the means for families to begin reducing demand for fossil fuels in their own homes.

There are also labor restrictions that the utility companies that are targeted in Goal 1 must follow in order to get the loans and grants associated with the programs. Companies must agree to provide training to workers so they are better positioned to change career fields. Companies must also agree to pay workers wages that can provide a middle-class life when they do the actual building of new renewable energy facilities and transmission lines. All these programs should help reduce the burden of moving toward a more climate-friendly energy system, either by providing financial incentives or by giving workers more money to defray the higher costs.

Goal 3 – Make the United States an industrial center of clean energy production. Finally, many of the tax credits and incentives to utility companies require the components to be manufactured in the United States. This portion of the legislation is designed to increase US manufacturing centered around clean energy production. By tying the incentives to US manufacturing, the goal is to increase demand for US manufactured products. This, in turn, would provide well-paying jobs for workers that can help these individual workers improve their lives and the lives of their families.

Climate Change and Human Action: The climate change portions of the Inflation Reduction Act represent the largest single investment in climate change ever passed by a democratic government. But we can rightly ask the question of why it took the government so long to begin investing in avoiding climate change. Similarly, we can ask why it took so long for reducing climate change to become a priority for the people, at least enough of a priority that the federal government would step in and provide the large levels of funding needed to meaningfully reduce the problem.

Robert Gifford describes what he terms the “Dragons of Inaction” to show why it can be so difficult to motivate people toward actions that will help reduce climate change. By Dragons of Inaction, Gifford is specifically referring to psychological barriers in decision making that make engaging in new or unfamiliar behaviors more difficult. There are seven of these.

- Limited Cognition. Limited cognition refers to the fact that thinking deeply about a subject we are unfamiliar with can be very difficult and require a great deal of energy. As a result, many people avoid it. After all, our brain has evolved to value efficiency in decision making. If something is very complicated or nuanced, or otherwise requires a great deal of effort, our brains often seek to short circuit the thinking process and rely on formalized scripts or previously learned information. Many thinking patterns can fall into this example including avoiding uncertainty and optimistic bias – a tendency to believe that everything will just work out in the end.

- Ideological Barriers. Climate change in particular has seen a lot of ideological ground staked out around it. It has become a topic with a lot of political ideology swept up in it. Some may believe that a completely free-market economy is the best and most proper way to run an economic system and therefore, providing any incentives to action is a bad idea because it runs against the ideals of a free-market.

- Social Norms. As we saw in Chapter 3, other people can have a huge impact on what we ultimately end up doing. If people we value think we shouldn’t be doing something, we probably won’t do it. Similarly, if we see that lots of other people that we value are doing something we are more likely to follow suite. Some city recycling programs are attempting to use social norms to encourage more recycling. In many cities, the bin for recyclables that can be collected by the city is separate from the regular garbage and also a bright, primary color – usually blue. Thus, when people put out their bins to be picked up, suddenly everyone on their block can see how many of their neighbors are participating in the city recycling program. As long as more people are participating than not, this is likely to drive up participation in the recycling program. However, other sustainable actions may not be adopted if people believe that everyone around them is not acting sustainably.

- Sunk Costs. The sunk costs phenomenon is a general finding in research on decision making that says people are less likely to change behavior if they have invested something in the old form of doing things. And particularly Americans have invested a tremendous amount of wealth and treasure into a system that uses fossil fuels as the primary source of energy. Americans have created a vast Interstate highways system for transportation to connect most of the country together. We have millions of refueling stations for gasoline powered vehicles in all areas of the country. There are vast, underground networks of pipes that bring fossil fuels to homes to use for heating. Similar systems are just now being put in place for more renewable energy sources, but they do not exist everywhere in the country. One might find it very difficult to find a place to recharge their electric vehicle in the middle of rural America, at least at the moment.

- Discredence. This dragon of inaction refers to people believing that experts, scientists, and politicians are not being completely honest with them regarding the threat of climate change, or are overplaying the threat of climate change to get something for themselves. Some people have a very negative view of experts – in some cases because of mistrust or in other cases because they have been repeatedly told that experts don’t actually know what they are talking about.

- Perceived Risk. Some people are less inclined to take action that would limit climate change because the new action is perceived as more risky than the old ways. For example, many people in northern climates are concerned that, if they purchase an electric vehicle, the cold would cause the battery to run out prematurely, potentially stranding them on the road with no way to get somewhere warm. Many people need to see the technology in action and see that their concerns about risk are not well founded before they will move toward the behavior in question.

- Limited Behavior. Our final dragon of inaction tends to come in a few different varieties. And, interestingly enough, this dragon does not involve complete inaction. Instead, it refers to actions that are either too little, too late or changes in behavior that negate the positive impact of a behavior that is made. The first example we call tokenism. Tokenism refers to very small behaviors that people make as a way to say that they have made strides toward helping climate change, when really they haven’t done anything. Maybe someone feels pressure to put out their blue bin every week so the neighbors think they are helping to recycle, but the only material that goes into the recycling bin are a few tin cans that get used over the course of the week. The other variety of this dragon is referred to as the rebound effect. This means that, when people make a positive change they sometimes then make a second change that negates the positive impact of the first change. For example, over the last decade LED lightbulbs have become quite popular. They use about 1/6th of the energy as old incandescent bulbs, last much longer, and generally have the same look as the old bulbs. As a result, people have generally adopted their use. However, because these bulbs us so much less energy, standards for lighting in new construction have started to change. People have started requesting more light fixtures in new construction because people generally like brighter, more well light areas in their houses. Since each individual bulb uses less energy, the increase in light fixtures feels justified. But, if the light bulbs use 1/6th of the energy, and we now expect to have 8 times as many light fixtures in our homes, we haven’t made any impact on climate change by adopting the new bulbs. In fact, it’s possible that we made the problem slightly worse.

Direction of the Problem

At the moment, we are near an important point in our efforts to stop the largest impacts of climate change. The most credible models indicate that global temperatures will continue to rise above the average seen between 1960-1990 through the end of the century. However, the actions we take right now can help determine how much they continue to rise and if temperatures can return to the 1960-1990 average. The carbon reduction elements of the Inflation Reduction Act represent one large scale initiative to reduce carbon emissions in the United States. However, climate change is ultimately a global problem that cannot be solved by only one country. And, thankfully, other countries are also increasing electricity production from renewable sources. China is the country with the largest solar power capacity – producing around 880 gigawatts of power from solar sources in 2024. This is enough electricity to power something on the order of 250 million homes, depending on how much electricity each home consumes. Saudi Arabia has a plan to produce 50% of its electricity from renewable sources by 2030. Large scale emitters like the United States must take the lead on decarbonization, but ultimately the world must follow to reduce the impact of climate change.

Summary

Climate change represents a large scale problem that will require many different approaches to solve correctly. The problem of increased carbon dioxide in the atmosphere is driven by the way humans have solved problems related to transportation, heating, and electricity production. Many so called “Dragons of Inaction” conspire to keep people from acting on this significant problem. However, large and small efforts – from federal legislation to local recycling initiatives are helping to slow the impact of climate change.

The transmission of energy through space, in this specific context using electromagnetic waves

A process where gases in the Earth's atmosphere trap heat from the sun, preventing it from escaping into space.

Feedback loops in which people change the environment and the environment, in turn, changes the people

In Environmental Psychology - short-term strategies designed to avoid the symptoms of a problem.

In Environmental Psychology - long-term strategies designed to actively deal with the causes of a problem.

A guaranteed level of power supply that is committed to be available at all times during a specified period, even under adverse conditions

Small behavioral changes made to say that one is helping with climate change. However, the behavioral changes are so small as to have a negligible effect on the climate system.

A phenomenon where improvements in energy efficiency lead to increased consumption, potentially offsetting some or all of the initial energy savings.