10 Individual vs. Collective Resource Use

Notre Dame is Burning

In 2019, the famous Notre Dame cathedral in Paris was undergoing renovation. Specifically, construction crews were working in and around the roof and the famous cathedral spire. Sadly, a fire started in the roof caused by either an electrical problem or a cigarette – no one was able to say for certain. Regardless, most of Paris was able to see the large flames coming out of the roof of one of the most famous landmarks in the city. Eventually, the fire consumed a good portion of the roof and the cathedral spire but, thankfully, the rest of the building was saved. Once the fire was out, restoration crews returned to inspect the damage and to see how much restoring the entire cathedral was now going to cost. The renovation project was already expensive. With all the extra damage from the fire, the costs were going to be astronomical.

Before the fire was even extinguished, several wealthy French individuals seemed to get into a bidding war to see who could pledge the most money toward reconstruction efforts. Francois-Henri Pinault – who ultimately owns Gucci – pledged 100 million euros (roughly 110 million U.S. dollars). When this pledge became public the Arnault family, which controls the wealth of the Louis Vuitton company, pledged 200 million euros. After that, members of the French billionaire class seemed to come out of the woodwork offering money to help with restoration. In total, approximately 900 million euros ($990 million U.S.) were raised during the first few weeks after the fire, with two thirds of those donations pledged by wealthy French businessmen. Now, in the time since the fire was put out, a very limited amount of the pledges by these businessmen have actually been collected, but this story is not about that. Instead, this story is about the optics of several wealthy French people getting into a bidding war over who can donate the most money to restore a fire-ravaged cathedral.

The optics were particularly important to the leaders of a political movement that was happening about this same time. Starting in November of 2018, large groups of individuals would congregate together on French streets wearing bright yellow traffic vests protesting for economic justice. This became known as the Yellow Vest Movement. The Yellow Vest Movement’s central argument was that too much of the taxation burden in France was falling on the lower and middle classes. This was especially troubling because prices for everything from fuel to groceries were increasing meaning most people in France were seeing a reduction in their standard of living. They were advocating for more taxation on the wealthy as well as increases to minimum wage and more government transparency on matters of funding.

The leaders of the Yellow Vest movement made many public statements decrying the opposition by wealthy individuals to their demands. These same wealthy people were pledging extreme sums of money to fix Notre Dame cathedral yet were using their money and influence to reduce government action on economic equity measures the movement leaders favored. The Yellow Vest leaders spent a lot of time pointing out the irony that all these wealthy individuals were pledging to help restore a Catholic Church. Not because they disliked the church, but because of the disconnect between having vast sums of money to donate and the messages written in the Christian Bible ascribed to the founder of the faith – Jesus of Nazareth. In multiple places within the Christian Bible, Jesus specifically states that those who hoard wealth are not following his teachings (see Matthew 19:24, Mark 10:25, and Luke 18:25). So why do you want to use your vast wealth to restore a Catholic Church? What does that say about how much the messages of the faith matter to you? Ultimately, the Yellow Vest leaders argued that if these wealthy individuals actually had that much money to give away to help restore an ancient building, then they also should also have plenty of money to give away some of it to the government in the form of a wealth tax so that the government could then afford to provide services and benefits to improve the standard of living for lower- and middle-class people. In essence, they argued that a building is just a building no matter how much cultural significance it may have but the people are the reason we’re all here and should be prioritized.

Depending on who you are and what your values are, you may come down on one side or the other of this debate, or even somewhere in the middle. But the important thing is that this debate does highlight an important tension in human decision making. We are often in tension between doing what is best for the individual and doing what is best for the collective. The collective may be a few other people, or it may be our communities, or it may be a nation. Regardless, sometimes what is best for us as individuals is not what is best for the collectives we belong to. How do we resolve that problem and how do we feel about the processes we take to resolve it? This chapter is all about how we decide to use resources and how we respond to inequity in the ability to use resources.

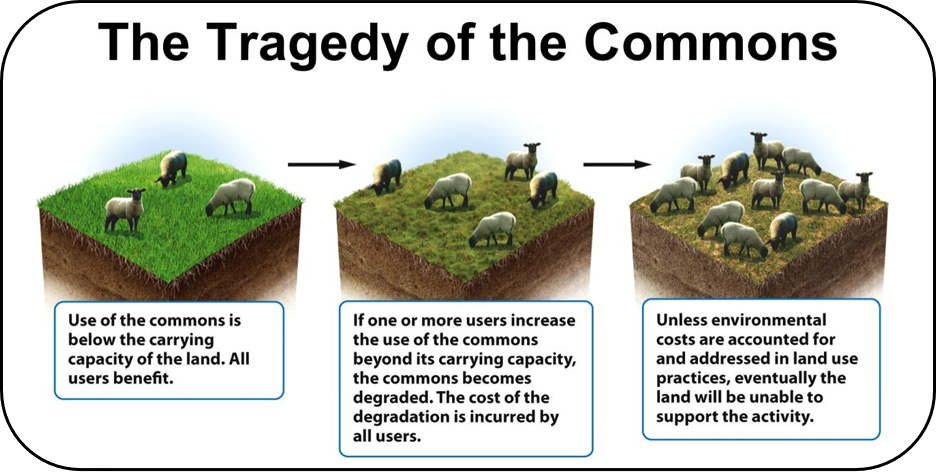

The Tragedy of the Commons

The classic source of much thinking about how humans are in tension between individual and community needs and how that tension applies to resource use is Garrett Hardin’s 1968 article “The Tragedy of the Commons.” In it, Hardin builds on thinking going back to the 1800s about collective ownership and individual responsibility. He presents a hypothetical in which there is a common grazing land for livestock that no individual owns by themselves. Instead, the land is held “in common” for everyone that needs to use it. He then imagines what individual livestock owners would do with this common land. In Hardin’s thinking, the owners would start thinking about all the extra profit they could be making by adding more livestock to their herds. After all, there are no costs to them for the land. So why not try to make some additional profit and make life better? Someone that doesn’t even own livestock may think that raising livestock would be a good way to make some extra side money and come into the market as well. Hardin envisions every livestock owner adding so many animals that the animals eat all the grass, and the common land becomes a dusty wasteland that can no longer support life.

This is Hardin’s entry point into the Tragedy of the Commons. His argument is that, under the economic theories of the time, individual short-term self-interest will always win out over long-term community concerns. Therefore, the only way to safeguard against humans destroying the environment that they depend on to live is to establish governments that will enforce regulations that restrain individual self-interest. Essentially, Hardin argues that one of the functions of government is to protect humanity from humans.

Hardin’s arguments gain a great deal of attention from federal policy makers in the 1970s. Through the research of Hardin and many other scientists focused on individual vs. collective problems – which came to be collectively called social dilemmas – policy makers began to see the importance of using regulation to ensure the continued viability of the environments around us and the resources they contained. This is the era in which the Environmental Protection Agency is founded, the Endangered Species Act, the Clean Air Act and the Clean Water Act are all passed. Regulations on manufacturing are enacted, both emissions from the factories themselves through the Clean Air Act and through regulations on the products created. We have already seen the importance of regulating products when we examined the 1972 regulation requiring automobile manufactures to install catalytic converters in new cars, leading to a reduction of lead emissions in the atmosphere.

Researching Social Dilemmas

The public policy implications of social dilemma problems were intense during the 1970s, but what about the actual research findings? How did we study social dilemmas and what are the major findings? Social dilemmas are typically studied using Game Theory. Game Theory is a large collection of ideas and mathematical approaches that seek to understand how decision making happens in the natural world and to provide a baseline of what “rational” decision making should look like. Since this is a psychology book, we will stick closely to Game Theory’s applications in humans, but Game Theory has many other applications in many other scientific disciplines including biology, economics, and biochemistry.

The most fundamental concept to understand from Game Theory as it relates to our discussion on individual vs. collective decision making is equilibrium. Equilibrium – sometimes called Nash Equilibrium after Nobel Prize winning economist John Nash who originated the concept – refers to a state in which everyone that is inside a situation and able to make a decision cannot make things individually better for themselves by changing their current choice. That can sound very academic and stilted, so let’s work through an example of a famous game used in both psychology and economics to study these things – the Ultimatum Game.

Ultimatum Game: Imagine that you are on a game show with an acquaintance you know somewhat well, but aren’t best friends with. You will be playing a game of “Ultimatum”. The game show host gives your friend the role of “First” and you the role of “Second”. The host then says that the First player will be given $100 and presents a crisp, $100 bill. But, she says, the First player cannot just have the money. No. The First player must share some of their money with you, the Second player. The First player gets total control over how much of the $100 to offer you and can choose any amount from 1 cent all the way up to the full $100. However, once the First player decides how much to share with you, the Second player gets to make a choice. You can choose to Accept the First player’s offer. If you do, you receive what you were offered, and the First player keeps the rest. Or you can Reject the First player’s offer. If you choose to Reject the First player’s offer, you don’t get any money, but neither does the First player. You both walk away empty handed. Take a pause and consider for a second. What is the lowest offer you would accept?

Let us connect back to our concept above of equilibrium and walk through the Ultimatum game step by step. Remember, to find equilibrium, we must change one player’s strategy and see if the outcome is individually better for that person. If it is, we haven’t found equilibrium. If a person making a different choice results in a worse outcome for themselves than before they started, we return to the original strategy and say we have found equilibrium. Let’s remind ourselves of the starting point. Before the game started, both you and your friend had nothing. So we are starting at $0. Now, let’s move ahead to the first choice, in which the First player must decide how much to share with you. And let’s imagine that your friend did what many American university students do and chose to split the money evenly, offering you $50. Then you, as the Second player, need to make a choice about accepting or rejecting and, again assuming you are like most American university students, you accept the offer. Both you and your friend now have $50 more than when you started, so you are both in a better position. That’s good, but what if there was a way for the First player to make a different choice that benefits them more than getting $50 but still satisfies the requirement that you both are ahead compared to where you started the game.

Let’s rewind our scenario. We’re back at the beginning again when both of you have $0. The host offers your friend $100 and says they must share some with you. And they choose to offer you $40, keeping $60 for themselves. Would you accept this offer? If you’re like most American university students, you likely would. After all, it’s still $40 for yourself which is a lot better than nothing at all. You might feel a little upset at your friend, but are you going to be all that upset over $10? Now let’s check again on equilibrium. Your friend improved their return by making a different choice. And we ended up in a place where you were both ahead of where you started. We satisfied our conditions. But we haven’t found equilibrium yet because we haven’t found the point where our conditions break.

Let’s rewind again. Now your friend offers you $25, keeping $75 for themselves. Notice that the same conditions apply, assuming you still accept the offer. And equilibrium suggests that you should. After all, having $25 is better than having $0. Let’s rewind again. Your friend offers you $5 keeping $95 for themselves. Now we are getting to a point where American university students start reliably rejecting offers. But should you? After all, you’re still getting $5. If you reject, you don’t get anything. $5 is greater than $0. Ultimately, Game Theory states that equilibrium in this scenario is that the First player should be offering the Second player $0.01, keeping $99.99 for themselves AND that the Second player should accept that offer since $0.01 is still greater than $0. But now ask yourself, would you accept a penny if your friend offered it to you on this game show? Game Theory says that you should, but are you willing to do that? Again, most American university students that participate in research like this are not willing to accept a penny when it is offered. And Americans are more willing to accept unequal offers than people in other cultures. Some researchers have taken the Ultimatum Game to East Africa. There, most offers below $50 are rejected. A similar result is found in interior Australia among aboriginal populations. In countries around the Mediterranean Sea, unequal offers are tolerated but offers lower than $40 are typically rejected.

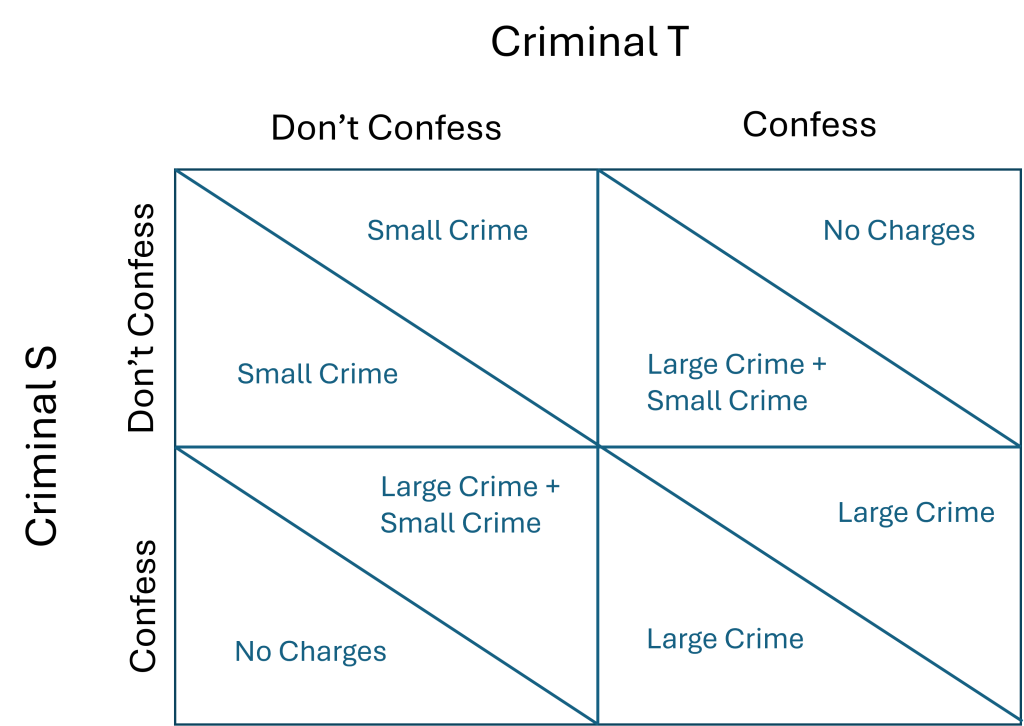

Equilibrium and Social Dilemmas: The key observation regarding equilibrium and social dilemmas, of which the ultimatum game is an example, is that actions corresponding with equilibrium are also usually a very individualistic set of actions. Many social dilemmas used in the laboratory to study individualism vs. cooperation are designed this way purposefully. One very common way to study social dilemmas in the lab is the Prisoner’s Dilemma. The Prisoner’s Dilemma is a social dilemma which is framed around a story of two people that committed a large crime and a small crime. They have both been arrested for the small crime and must decide if they will keep quiet about the large crime or if they will confess to the large crime and become a witness against the other person in exchange for immunity while the other person is sent to prison for both the large and the small crime. The only complication is that if both people confess to the crime, the prosecutor doesn’t need a witness anymore, both will be prosecuted for the large crime, but the prosecutor will forget about the small crime. Pause here and consider before going on. What is equilibrium in the Prisoner’s Dilemma?

To find equilibrium in the Prisoner’s Dilemma, let’s consider the situation entirely from the point of view of one criminal. We will call this criminal Criminal S and his partner in crime Criminal T.

Criminal S does not know what Criminal T will do. He may have ideas, but can’t be certain. So, he must evaluate his two choices. If he chooses to side with his partner, Criminal T, and not confess to the large crime one of two things will happen. Either Criminal T will also not confess to the large crime and they will both be prosecuted for the small crime, or Criminal T will confess and Criminal S will be prosecuted for the large crime and the small crime while Criminal T goes free. But what if Criminal S chooses to confess and be a witness against Criminal T? Well, again one of two things will happen. If Criminal T decides to not confess, then Criminal T gets prosecuted for the large and small crime and Criminal S goes free. Or Criminal T also decides to become a witness, which means both Criminal S and Criminal T are prosecuted for the large crime. Now, let’s compare our possibilities from Criminal S’s point of view. If Criminal S chooses to not confess, either he will be prosecuted for the small crime or he will be prosecuted for both the large crime and the small crime, depending on what Criminal T does. If Criminal S decides to confess and become a witness, he will either go free or be prosecuted for the large crime. So the choices being compared are [Prosecuted for small crime vs. Go free] or [Prosecuted for large and small crime vs. Prosecuted for large crime]. In both cases, Criminal S is better off individually if he turns witness. If Criminal T doesn’t confess, Criminal S goes free rather than being prosecuted for the small crime. If Criminal T does confess, Criminal S is prosecuted for the large crime, but not both the large crime and the small crime. It doesn’t matter what Criminal T does. Criminal S will always be individually better off by offering to be a witness. But what about the collective? Because the exact same incentives are operating on Criminal T, making it individually better for him to confess regardless of what Criminal S does. So then they should both confess. But now they’re both being charged with the large crime – which we can imagine carries a prison sentence – rather than both being charged with the small crime – which we can imagine would result in a fine and maybe some community service. Is it better for both of them to choose prison when both getting fines is a possibility? Maybe for society, but definitely not for them.

We see the same dynamics play out in so-called resource dilemmas, which will be the focus of the remainder of the chapter

Resource Dilemmas: Resource dilemmas are a similar type of problem to the ultimatum game or the Prisoner’s Dilemma, just scaled up more than two people. There are two general types – common’s dilemmas and resource allocation games. In common's dilemma games – also sometimes called give-some-games – each individual in the situation has control of some amount of resources. Each individual is asked if they want to donate some of their resources to a common cause. Having resources is made valuable in some way, sometimes by offering raffle tickets for a cash drawing, sometimes by offering candy for having so many, etc. The point is that people want resources but are asked to donate some. Then there is some way to reward the individuals for their donations – sometimes by returning a percentage of the donations as rewards split among everyone in the group or sometimes by providing a reward only if the total group contributions are above a certain threshold. In resource allocation games – also sometimes called take-some games – the situation is reversed. There is a communal pool of resources that everyone has access to. Each individual is asked if they want to take some of the resources from that central pool. Again, resources are made valuable so people want them. There is also a way to reward the individuals for harvesting resources responsibly, sometimes by having the resource pool grow by a percentage of the resources that are left and sometimes by providing a reward if total harvests are below a certain threshold.

In these types of games, equilibrium is again a very individualistic course of action. Remember that to satisfy equilibrium, we need to reach a situation where someone gets the maximum return and changing their actions does not make things worse. In the common’s dilemma, any contributions are points that you no longer have. So equilibrium would say that you should minimize the amount of points you give. In resource allocation games, any resource that you fail to harvest is profit that has been left in the pool that you could be taking advantage of. Thus, equilibrium would suggest taking the maximum number of resources. Following pure equilibrium would generally tell us that we should contribute as little as possible in the common’s dilemma game and harvest as much as possible in the resource allocation game. However, notice that these are very short-term solutions that don’t allow for the creation of larger, long-term rewards. In the common’s dilemma, no large rewards are given. In the resource allocation game, it’s possible that the entire resource will become depleted very quickly.

We should be thankful, therefore, that in most studies that look at how people behave in these types of situations, people tend to be much more cooperative than what following equilibrium would predict would happen. In studies using the ultimatum game, the most common offer is $60 for the First person and $40 for the Second person. In studies using the Prisoner’s Dilemma, somewhere between 66-80% of pairs choose to cooperate with their partner and remain quiet about the larger crime. This percentage is similar in common’s dilemma and resource allocation games as well. A majority of participants in studies that use common’s dilemma and resource allocation games tend to either contribute enough to get a reward or control their harvesting so that they get a reward. In my own studies using a resource allocation game called Fishbanks, nearly 80% of undergraduate groups maintain not just one but two populations of fish that would be depleted if too many fish were harvested.

From this data, we can make a very interesting conclusion. Humans are much more cooperative and long-term oriented than what equilibrium would predict. That conclusion is a very hopeful one. In the next chapter we will discuss climate change, which can be generally thought of as a giant take-some game. If humans were not exceptionally cooperative in the face of social dilemmas, we might already have used so much of our planet’s fossil fuel resources we would not have the ability to reverse climate change anymore. As it stands, we still can return the climate system to 1990s temperatures by the end of this century.

Summary

How humans cooperate with one another for scare resources has been a high interest research topic since the 1960’s. Most studies begin with an assumption of behavior moving towards equilibrium. However, in many situations, equilibrium results in a net loss of potential rewards. Thankfully, across a variety of situations, humans tend to behave much more cooperatively and long-term oriented than equilibrium would predict. This has important implications for how we will be able to get ourselves out of our currently unfolding climate crisis.

A situation where individuals acting independently and rationally according to their own self-interest deplete a shared resource, ultimately harming everyone involved

A large collection of ideas and mathematical approaches that seek to understand how decision making happens in the natural world and to provide a baseline of what "rational" decision making should look like.

(a.k.a. Nash equilibrium) a situation in which no person in a decision making situation could individually gain by changing their own strategy, assuming all other peoples' strategies remain the same

A game in which players must decide how much of their resources to give to the creation of a community resource that benefits all players and how much to retain for themselves.

A game in which players may harvest resources from a central pool with community-wide rewards given when players harvest the resources in a sustainable way