9 Natural Disasters

The Pandemic Before COVID-19

In September of 2005, an epidemic swept through a distant land. The 2005 epidemic affected nearly everyone in the land, leaving bodies in the streets of nearly abandoned cities. It was so deadly that it forced factions that were usually aligned against one another to band together in cooperation. It also demonstrated just how vulnerable our information system is to misinformation campaigns centered around uncertain and unpredictable events. You may not have even heard about this epidemic, but it was responsible for multiple scientific studies that shaped our understanding of how people would respond to the COVID-19 pandemic fifteen years later. The main reason you may not have heard about this epidemic is that it occurred in a video game.

September 2005 saw World of Warcraft at nearly the height of its popularity. This was a Massively Multiplayer Online Role Playing Game (MMORPG) in which thousands of players would log into the same server to play in the same world. The game featured the typical fantasy video game themes of elves, dwarves, gnomes etc. all going off on Important Adventures, killing large monsters, and returning with fantastic treasures. Blizzard, the company that developed World of Warcraft, introduced a new zone in September of 2005 intended for the most dedicated and coordinated of players. The final “boss” of this zone, and the most difficult encounter, was a summoned demi-god centered around the theme of blood. As the players fought this monster, they would receive an affliction on their character called “Corrupted Blood”. This curse would slowly kill their character unless a healer-type character came along and cured it. The curse would also spread to other players nearby, so it was something that needed to be constantly contained by the healers. Because the characters were generally highly skilled adventurers, they typically had the resources needed to survive the curse and keep fighting until a healer came along.

Once the characters defeated the level “boss”, they generally went back to their home cities. Blizzard understood that Corrupted Blood could cause a major problem in those cities if it were to get out, so they took specific steps to ensure that the curse only remained in their new zone designed for those highly dedicated players. However, they forgot about one thing. Certain types of characters were able to recruit animal companions to fight with them. These animal companions were generally much weaker than the character and died quickly if they were hit with the curse. However, the character could revive their animal companion later if they died. And Blizzard’s programmers forgot that when these characters revived their animal companions, the animal companions returned with all the status affects that had been impacting them when they died. And so, when the Hunters returned from their big adventure and revived their animal companion in their home city, the Corrupted Blood was let loose.

In the cities, the curse caused a much larger problem than it did in the new zone. First, the new zone was designed to only let 20 players in at a time. By contrast, the cities contained hundreds of players all trying to get other business done in the game. Second, most of the characters in the cities were not the highly dedicated, maximum-level players that would enter new, difficult zones. Most were lower level, beginning players just trying to figure the game out. And third, the cities contained non-player-characters (NPCs) that were designed to exist within the game always. Sometimes, bored players would attack these characters just to see what would happen. The developers knew these characters needed massive amounts of hit points or people would just go around killing them constantly. This meant that when the NPCs became infected with the curse, they wouldn’t die but they could spread it to unsuspecting characters who had no idea the NPC was sick at all. All of this created a situation where the curse spread like wildfire throughout the land leaving thousands of dead in the streets (though remember, this is a video game and players could just log back in and revive themselves if they wanted to)

If you are unfamiliar with video games, all this talk may seem a bit weird. However, scientists saw an amazing opportunity they had been given to study an epidemic. Epidemics don’t happen every year. During the time of this virtual epidemic in 2005, the most recent epidemic had happened in 1968 and the most recent pandemic happened in 1918. The Corrupted Blood epidemic represented a space where scientists could gather much needed data about how people would respond to an epidemic in modern times. Of course, scientists recognized that this was a video game and they couldn’t analog everything exactly to the real world. After all, as I mentioned above, you get to respawn in a video game. You don’t get to respawn in real life. However, it is important to remember that the characters in the game were played by people. And in the face of a virtual epidemic, they still acted like people.

Hazard vs. Disaster

The most important distinction to make in this area is the distinction between a hazard and a disaster. A hazard is the possibility or the perception of the possibility of a dangerous event occurring.

A disaster is the actual occurrence of the dangerous event. It is the realization of the hazard. In our World of Warcraft example, the hazard of the curse getting out existed as soon as the new zone was introduced to the game. However, it took some time before even the highly coordinated players could get to the final boss. This means that the hazard of an epidemic existed even though the actual disaster had not yet taken place. The correct mix of circumstances needed to happen before the disaster could occur.

Types of Disasters

Another critical thing to understand with disasters is that they are divided up into three general categories. This helps us understand the causes of the disaster and what lead to each type. This distinction is also sometimes important to insurance companies that have specific riders in certain policies (water damage policies for instance) that will pay out in the event of one type of disaster but not another.

Natural Disaster: A natural disaster is a disaster caused by natural forces. These are what we most typically think about when we think about disasters. Examples of natural disasters include hurricanes, tornadoes, or wildfires sparked by lightning strikes. The critical element is whether the disaster had a force of nature as the cause of the incident. Understanding the ultimate cause of a disaster can be fairly consequential. For instance, in my example above about water damage insurance policies, most policies will not pay out if water damage is caused by natural flooding. One would need to purchase separate flood insurance to pay for that type of damage.

Technological Disaster: A technological disaster, on the other hand, refers to a disaster that is caused by the unintentional failure of human technology. The largest ecological disaster in United States history began in April of 2010. The Deepwater Horizon offshore drilling facility, which was drilling for oil off the coast of Louisiana exploded causing the deaths of 11 people and creating a massive oil spill. Thousands of square miles of ocean and coastline were contaminated and required a large-scale cleanup effort. We call this a technological disaster because it was the failure of technology and human equipment that caused the disaster in the first place. While the effects were mostly experienced by the natural world, with oil contaminating habitats for both shoreline and marine life, since the cause of the disaster was a failure of technology, we refer to this as a technological disaster.

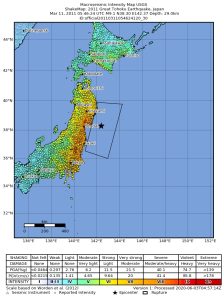

Complex Disaster: Finally, there are complex disasters. Complex disasters have a variety of initial causes. The hallmark of a complex disaster is that natural forces and technological failures combine to create a much larger disaster than would have occurred with either one alone. For example, in March of 2011, a massive 9.0 undersea earthquake occurred off the east coast of Japan. Within minutes, an enormous tsunami was racing toward the coast. This wave would eventually reach 14 meters (46 feet) high, slamming into the coast of Fukushima prefecture. This initial wave was so large and hit so fast it caused the deaths of 20,000 people. If this was the only thing that had occurred here, this would be a tragic natural disaster. However, it was not the only thing that happened.

Nearby was the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant. This plant was built with the possibility of tsunamis in mind. The plant had earthquake sensors that would immediately shut down the reactor if a large enough earthquake was detected. Those sensors worked and the reactor was immediately shut down upon detection of the earthquake. The plant also had flood walls built to hold back any large waves. However, this is one of the largest recorded waves to ever hit Japan and the walls were not built that high. Flood water washed over the walls and into the plant.

The nuclear reactor had shut down by the time the tsunami hit the coast of Fukushima prefecture. However, nuclear reactors produce a lot of heat. This is how they create electricity. The nuclear reaction produces heat which causes water pumping through the reactor to turn to steam. Steam powers a turbine which creates electricity. Even after shutdown, nuclear reactors have a lot of leftover heat that needs to be constantly taken away. Because the electricity produced by the plant is gone, the Fukushima Daiichi plant had diesel engines pumping water through the reactor cool the reactor down. However, when the tsunami came over the plant’s floodwall, the floodwater entered the engine room knocking the diesel engines offline. This led to a buildup of heat within the reactors causing a meltdown in three of the four reactors at the plant – which is when the fuel rods melt and nuclear fuel leaks into places it is not supposed to be causing a radiation disaster.

As the disaster unfolded, nearly 80,000 residents were told to relocate for safety reasons. This compounded the tragedy caused by the tsunami as many residents were unable to properly process the trauma of lost loved ones, lost homes, and lost livelihoods. Instead of being given time to grieve, they had to be removed from the location or risk exposure to deadly radiation. This is a complete example of a complex disaster. Multiple forces had to come together to create the tragedy. From the initial earthquake and tsunami, to the walls that were not tall enough to handle a tsunami larger than any in recorded Japanese history, to the cooling system being knocked offline by that tsunami, a combination of natural and technological forces combined to create this disaster.

Responding to a Disaster

When it comes to humans and disasters, one of the most critical questions is how people respond when disaster strikes. When asked, many people will assume that the most common human response to a disaster is panic. You may even see this when politicians talk about why they were not more forthright with information regarding the scope of a disaster. Very often, you will hear them say they did not want to cause a panic.

It may surprise you, then, to learn that panic is not the most common response to disaster. Certainly, people will panic if there is an immediate threat in a specific location they can point to. Absolutely, people in Fukushima prefecture panicked at the sight of a massive, incoming tsunami. But that is the exact time people will panic: when there is an immediate, localized threat to life and property. During the Deepwater Horizon disaster, people panicked during the initial explosion, when it was unclear if the entire rig was about to fall down around the workers, but nobody panicked during the oil leak portion of the disaster even though we could argue that portion had more long-lasting consequences for more people. Officials certainly tried several ridiculous sounding ideas to get the oil spill to stop, but they weren’t panicking. Similarly, many people do not panic when they see tornadoes – especially if they are in their own homes or near a shelter they feel confident in. Rather than panic many people will confidently film the tornadoes with their cell phone cameras.

When we think about human response to disaster, it can help to think about it in three phases, 1) before the disaster occurs, 2) during the disaster, and 3) after the disaster.

Before the Disaster: Before the disaster, we exist in the hazard phase. A potential disaster exists, but no one knows how close or far away that disaster may be. As a result, people are rarely prepared for a disaster when it occurs. This is not to say that it would be reasonable to ask people to prepare for every possible disaster. We do not know what we do not know. Uncertainty about what could happen means that the list of possible disasters is too long to prepare for. Therefore, we should not be surprised when people are caught unaware as a disaster begins to unfold.

During the Disaster: Once the disaster occurs, humans very often display a remarkable quality. As long as the person is not concerned for their own life or the lives of close others, during disaster people very often form into therapeutic communities to cope with the disaster as it disrupts peoples’ lives. Therapeutic communities are groups of people that provide social support to one another. They may not know one another, or even have had any sort of connection to each other before the disaster occurred. But still, they help one another through the disaster creating a sense of community. In this way, groups of people help one another use active coping strategies to deal with the life upheaval that comes with disaster.

In the northern Great Plains of the United States, flooding is a very common natural disaster. Because it is so common, people generally know how to prepare for a flood and to cope with one as it happens. Very often, a flood fight involves a community banding together to fill sandbags, using those sandbags to build dikes, and monitoring the dikes for leaks to ensure they are holding. Community members come from all over, even if their homes are not in the direct path of danger from the flood. In fact, people whose homes are not in danger tend to show up in greater numbers as they are not dealing with the emotional trauma of having their home threatened by forces one cannot control. This is the essence of therapeutic community. Humans seek to reach out to one another to help through disasters whenever we can.

Therapeutic communities even occurred during the Corrupted Blood epidemic. As the plague spread through cities, many players abandoned the main population centers and ran for more outlying areas. However, players wanted to be sure that these players leaving the cities were not bringing Corrupted Blood with them. Healer characters set up stations at the borders between the city areas and the outlying areas. When a character would come through, the healer characters would ensure that the character coming through was not infected with Corrupted Blood or, if they were infected, that they were cured of it before they went to the other zones. Many people chose to do this with their leisure time. Remember, World of Warcraft is ultimately a video game. People were paying monthly subscription fees to log into a game that they would normally play to feel accomplished or to destress. During the Corrupted Blood epidemic players spent that time standing around well-traveled paths ensuring that sick characters did not travel through their checkpoints

Not everyone experiences the benefit of therapeutic community. For some, the emotional trauma is overwhelming and they are not able to come together with others in social support. For these individuals, withdrawing is the most common response to a disaster. This is done more as an avoidant coping strategy to deal with the emotions caused by the disaster rather than the life circumstances that are causing the emotions. A focus of disaster research in psychology focuses on people who do not feel the healing effects of therapeutic community. Much more research needs to be done on this topic before we can make more definitive statements about these individuals.

After the Disaster: After a disaster, life tends to become more predictable again. For some people, this leads to a restructuring of priorities and a better sense of fulfillment from life. Practitioners call this phenomenon post-traumatic growth. In post-traumatic growth, people find meaning and satisfaction in elements of life that used to cause them stress and worry. They may de-prioritize work to focus more on family, for instance. Many people with families report a “blessing in disguise” of the lockdowns associated with the COVID-19 pandemic was getting to know their family members better.

But post-traumatic growth is not constant nor inevitable. Some people, in field studies about 17% of people, experience post-traumatic stress. This is a negative emotional state that persists even after the disaster has passed and life has become predictable again. It may result in irritability, nightmares, mood swings, obsessive or intrusive thoughts about the traumatic event, etc. Post-traumatic stress is the most common negative psychological reaction to disasters and the effects can last for many years or even for entire lifetimes.

Summary

Disasters can take many forms be they natural, technological or complex. Psychological reactions to disasters tend to be very similar across the different types. Before a disaster happens, people are generally unaware of the hazard that exists to them. As the disaster unfolds, people tend to form into therapeutic communities to help each other through the disaster. After a disaster, people can experience both post-traumatic stress and post-traumatic growth. Much more research is needed to understand what risk factors could lead someone to experience the stress effect rather than the growth.

The possibility or the perception of the possibility of a dangerous event occurring.

The occurrence of a dangerous event. The realization of a hazard.

A disaster caused by natural forces. Examples include hurricanes, tornadoes, floods, and wildfires (not set by humans)

A disaster caused by the failure of human technology

A disaster in which natural forces and human technological failures combine. Often creates a much larger disaster than would have occurred with either one alone.

Groups of people that provide social support and comfort to one another during difficult times

A way of dealing with stress by avoiding or distancing oneself from the source of the stress. Done to avoid the negative emotions the stressful situation brings.

Describes the positive psychological changes that can occur after experiencing a trauma. Changes can include a better sense of meaning and fulfillment from life, restructured priorities, or a new focus on positive interactions with family and friends.

An anxiety disorder that can develop after a person experiences or witnesses a traumatic event.