12 Social Design and Emergent Behavior

Propinquity in Action

In 1947, MIT was admitting a lot of additional students. Nearly all the additional students had served in World War II, making them eligible to have some or all their college tuition paid for by the GI Bill. Because so many of these new students had been soldiers, they had different needs than the typical college student. Specifically, many of them were married and wanted to live in married housing on campus. So MIT began construction on many additional housing units that would be suitable for married couples. Once the construction was completed, students began to move in and Leon Festinger, Stanley Schachter, and Kurt Back decided to investigate whether design elements of the buildings people were occupying were related to friendship formation. They distributed surveys to everyone in the new married housing units after they had lived there for at least a half a year. Those surveys asked them who their friends were and where those friends lived.

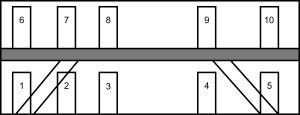

The results of those surveys showed very interesting patterns when compiled all together. First, they showed that most people had friends that lived in the same building as they did. There were many such buildings with many couples all in the same phase of life, but most people had made friends within the building they lived in. Inside each building there were also interesting patterns. It was most common for someone to be friends with another couple that lived right next door. It was also the most uncommon for couples that lived at each end of the building to be friends with one another. Other patterns also emerged. People that lived on the 1st floor of the two-story structure tended to have friends that also lived on the first floor. Except if you lived at the end of the hallway, where the two stairwells were located. In that case, those couples were more than 2.5 times more likely to have friends that lived on the upper floors.

The researchers coined the term propinquity to refer to the relationship patterns they uncovered. They were describing ways that the physical environment was encouraging or discouraging interaction among individuals. If you lived right next to someone, it was very likely that you would eventually bump into each other. And bumping into each other is a good way to begin talking with one another Once you are talking to one another, you are more likely to eventually form a friendship. This is also the explanation for why the first-floor people at the end of the halls had many more friends that lived upstairs than people that lived in the middle of the floor. They were more likely to see and bump into people that lived upstairs because of their proximity to the stairwell.

Social Design

If we take the results of this classic study seriously, we may think that the architect has a lot more influence over our lives that we ever imagined. We have likely never met the person that designed our college dorm or apartment. But their choices on where to place stairwells, how many floors to have in the building, and whether doors of apartments face each other down a central hallway may have a large influence on who we become friends with. If you believe this set of results, you are beginning down the road of architectural determinism, a philosophical position that believes that the spaces we inhabit in the built environment determine a great deal of how we exist socially. At its most extreme, believers in architectural determinism propose that everything from cooperation, community engagement, drug abuse, and divorce can be predicted from architectural design.

We will not go so far in this book. While it is reasonable to evaluate the impact context can have on social behavior, we will not go so far as to say any specific behavior is inevitable inside of a particular design. Instead, we will advocate for a process of social design in which the needs of the people using the space are addressed in elements of the design. Rather than determinism, we will advocate for the eventual users of the space to have input into the design.

An example of Social Design: As a classroom teacher, there is one element of classroom design that I intensely dislike. This element is in nearly every classroom I’ve ever been in and it makes the task of teaching how I want to teach that much more difficult. In most modern classrooms, there is a projector and screen that can be used to display a slide presentation. There is also usually a chalkboard or whiteboard that can be used to draw things on as the instructor is talking. Having both of those things in the classroom is great, but the thing I dislike is that the projector screen and whiteboard almost always occupy the same wall space, so that the screen covers up whatever is written on the white board when the screen is being used. This makes the whiteboard nearly unusable when the screen is in place.

The placement of the white board and projector screen is very often a case of top-down expectations. Most of us have experienced a classroom and been in classrooms. And the typical model of those classrooms – even though we know it isn’t necessarily the best way to learn – is of an instructor standing at the front of the room while all the students face the same direction and receive information. If you are an architect designing a classroom, and this is your dominant model of how things work, it may make perfect sense to put all the equipment that displays information at the front of the room. However, it is possible that by designing the space in this way, one is limiting some interesting and useful behaviors from emerging that could improve the experience for everyone.

Design Popularity

Are popular designs always good? If we design a space for someone and they say that they like it, should we accept that we have done a good job? What people like and don’t like from a design perspective is a very complicated topic. One thing we know for certain about popularity – at least when it comes to ideas – is that popular things tend to be just slightly different from what someone is already used to. You might write the greatest song in the world, but if it sounds too wildly different from what the people are already used to, they will not have a way to understand that song. You’ll end up like Marty McFly on stage at the end of Back to the Future.

One space in architectural design and city planning that this issue comes up in is roundabouts (a.k.a. traffic circles). When I say roundabouts, I am talking about a very specific type of traffic control device. They are placed at intersections with Yield signs at each entrance. When the roundabout is clear, cars may enter the circular lane and go around until they find their intended exit point. The rules of the roundabout are quite simple – entering traffic yields to traffic already in the roundabout, traffic inside the roundabout does not stop, follow the painted lines, and never turn left – but the results can be truly spectacular. Roundabout installation has been shown to reduce fatal collisions at intersections by approximately 90%. There is also evidence that roundabouts are better at keeping traffic flowing compared to traditional intersections. This effect greatly explains why the number of roundabouts in the United States has exploded over the past 20 years. They are a phenomenal design that results in safer transportation. However, there is just one problem. When people find out that a city is planning on installing their first roundabout, very few people like the idea.

Roundabouts are a type of traffic control that is unfamiliar to many people in the United States, particularly in rural areas. Because it is unfamiliar, people are unsure how to navigate them. They may not know or understand the rules that keep traffic flowing effectively in a roundabout. They may find the process of exiting a roundabout difficult because it is so different from their typical driving behavior. And because of this, they may be willing to forgo the positive benefits of the design in favor of something that doesn’t work as well but fits better into their own set of expectations and experiences.

Emergent Behavior

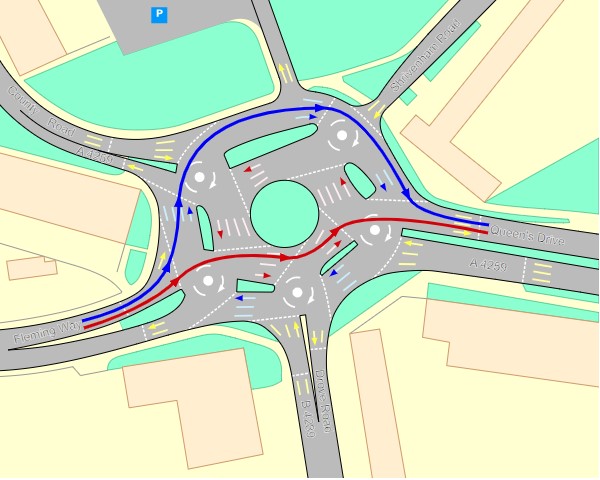

The extreme example of beautiful, effective emergent behavior that receives poor reviews from people that have never experienced the situation before is found in Swindon, U.K. at a large roundabout nicknamed the “Magic Roundabout”. The Magic Roundabout is a large-scale traffic circle that exists at the meeting point of five different major roads. Its design is essentially five different roundabouts all pushed together. One can enter the roundabout and go all the way around and exit out at their intended destination. However, on busy traffic days, drivers are able to transfer themselves between circles inside the roundabout and cut off a great deal of time in traffic. Drivers can do this by following a small, simple set of rules about how traffic should flow in the roundabout. As long as you yield to vehicles already in the roundabout, follow the painted lines and do what you can to avoid collisions, you will get through this traffic feature quickly, safely, and efficiently.

The Magic Roundabout is a great example of emergent behavior – when a small set of rules can create incredibly complex behavior among groups. And a key piece of social design is attempting to understand if the spaces one is designing will create positive emergent behavior or not. With the Magic Roundabout, traffic flows incredibly well through it given how complex it can seem when viewed from the outside. Very few accidents occur in the roundabout, traffic jams almost never happen, and fatalities are nearly non-existent.

However, emergent behavior can also work in a negative direction as well. There are several large-scale housing developments that fit this model. Architects often design housing with the best of intentions to serve large numbers of people in an affordable way, but end up creating feedback loops that reward negative behavior. One famous example of this was the Pruitt-Igoe housing complex in St. Louis, Missouri. The complex was intended to be 2,870 affordable housing units in 33 different 11-story buildings. The architect for the project won design awards for the project because of the many innovative, cost-saving elements that were implemented in this project. On the strength of this project and others, they eventually won the contract to design the World Trade Center. However, those same innovative, cost-saving elements created negative emergent behavior that eventually resulted in the buildings closure and demolition 16 years after it opened.

To save costs, elevators were designed to only stop on every 3rd floor. Elevator doors and the support structures needed for an elevator door are very expensive. So, cutting down the number of doors needed from 11 to 4 in each of the 33 buildings was a tremendous savings. It was reasoned that stopping on every 3rd floor would be acceptable because all residents could either get off on their own floor, or only need to walk one floor up or one floor down to get to their unit. Other costs saving measures included reducing the total size of the apartment and reducing the size of the kitchen appliances. The smaller kitchen appliances created a problem for families moving into the complex. They simply were not large enough to cook for a family, which meant that families did not move into the complex at the rate expected. Because the profit margins on affordable housing can be incredibly small, the fact that families did not move in meant that the complex was never profitable. To save money, maintenance schedules were reduced. And this reduction in maintenance coupled with the stairwells that were required for most people to get to their apartments created a very dangerous situation.

Lights in the stairwells went out and were not replaced. Each building had so many residents that it was impossible to know who lived in the building and who did not. And people with ill intentions that did not belong in the building knew that people had to navigate the stairwells to get home. Soon the stairwells became havens for violent crimes like assaults, robberies, and rapes. This led to a feedback loop in which more and more people moved out of the building because of safety concerns, further eroding the budget for the building, which led to continued maintenance issues, which fed the dangerous behavior. By the time demolition began 16 years after opening, more than half the buildings were completely abandoned and only 600 people lived in the entire complex of 2,870 units.

Predicting Emergent Behavior

At this point, it would be nice if I could give a list of easily digestible guidelines for when emergent behavior will create feedback loops generating positive behavior rather than negative behavior. However, the current state of knowledge does not allow me to do that. Fields that study emergent behavior generally require very intense study and employ reasonably complex methods of answering questions which are beyond the scope of this book. There are some simpler findings that can be reported, but generally these findings are somewhat fragmented and not connected to a larger framework. We know that cooperative behavior tends to emerge among small groups that have a uniform expectation. The surprising result from that means that groups that have a uniform expectation that none of their group members will cooperate still tend to move toward cooperation. But a great deal more research needs to be conducted in this area before we have a more understandable and applicable set of guidelines of how to create positive emergent behavior.

Summary

The design of environments can have a large effect on how people act within that environment. It can change who people become friends with, whether they feel safe in their home, and the severity of traffic accidents. And while understanding emergent behavior is an important area, there are few systematic studies that examine the phenomenon in people.