5 Crowding

Hungary’s Bold Income Tax Initiative

In February 2019, the president of Hungary announced a bold policy initiative. In fact, it was one of the largest investments in social programs in Hungary’s history and took the country from one of the lowest investors in social programs in Europe to one of the highest. The big headline from the announcement was that women citizens of Hungary that have four or more children would be exempt from income tax for the rest of their lives. In addition, he announced several subsidy programs to help with costs associated with raising multiple children that families could take advantage of if they had fewer than four children. These programs include things like government help paying for daycare, groceries, and diapers.

The introduction of this policy may come as a surprise to some. After all, the estimated human population of Earth has just passed 8 billion people. Keeping all these people alive, fed, and growing requires an enormous amount of resources. So why would a government that for years has avoided investing in social programs that reduce the cost of having children suddenly make a massive investment in incentivizing its population to have children?

The answer to this question has a lot to do with how we think about crowding in modern times. For multiple centuries now, the idea of overpopulation has sunk into the deep levels of peoples’ ideas of how the world works. However, to truly understand the idea of crowding and how crowding works in relation to human populations and demographics we must examine both the history of crowding and how ideas about crowding have changed.

Crowding

The idea of crowding faces what is called a levels-of-analysis problem. Imagine this type of problem as levels of magnification. If you are zoomed all the way in, you can see one set of important elements, processes, and conflicts. But if you zoom out one level, you see an entirely different set of important elements, processes, and conflicts. And if you zoom all the way out, the things that seemed very important at the smaller levels don’t seem to matter at all at the largest levels.

Individual level. On an individual level, crowding is very much related to the idea of interpersonal space. When our interpersonal space is being violated, we tend to feel crowded. This also means that on the individual level, feelings of being crowded are very context dependent. We could have huge numbers of family and loved ones around us and not feel crowded at all. However, we could be in an empty room with one other stranger and feel very crowded. Return to the chapter on Personal Space for a review of the contexts and situations that lead to individuals feeling crowded.

Group level. When we expand out to the group level, things look a little bit different than they did with interpersonal space. Context still matters regarding who the people are that around you for whether or not you feel crowded. For instance, groups of nuclear families that are all related by a common bond can come together in a relatively small space and not feel crowded. Think about loving families that all gather in Grandma’s small house for a holiday meal. On the other hand, two rival groups may need to have a buffer zone between them lest they invite unnecessary conflict between one another. Think about the rival gangs in works like West Side Story or The Outsiders. In both of those cases, rival groups have a well defined territory that is known by both groups and when that territory is breached, there is conflict. So the who still matters in group level research. However, research on crowding at the group level is much more concerned with basic living processes. Do people remain happy, healthy, and thriving when surrounded by large numbers of others?

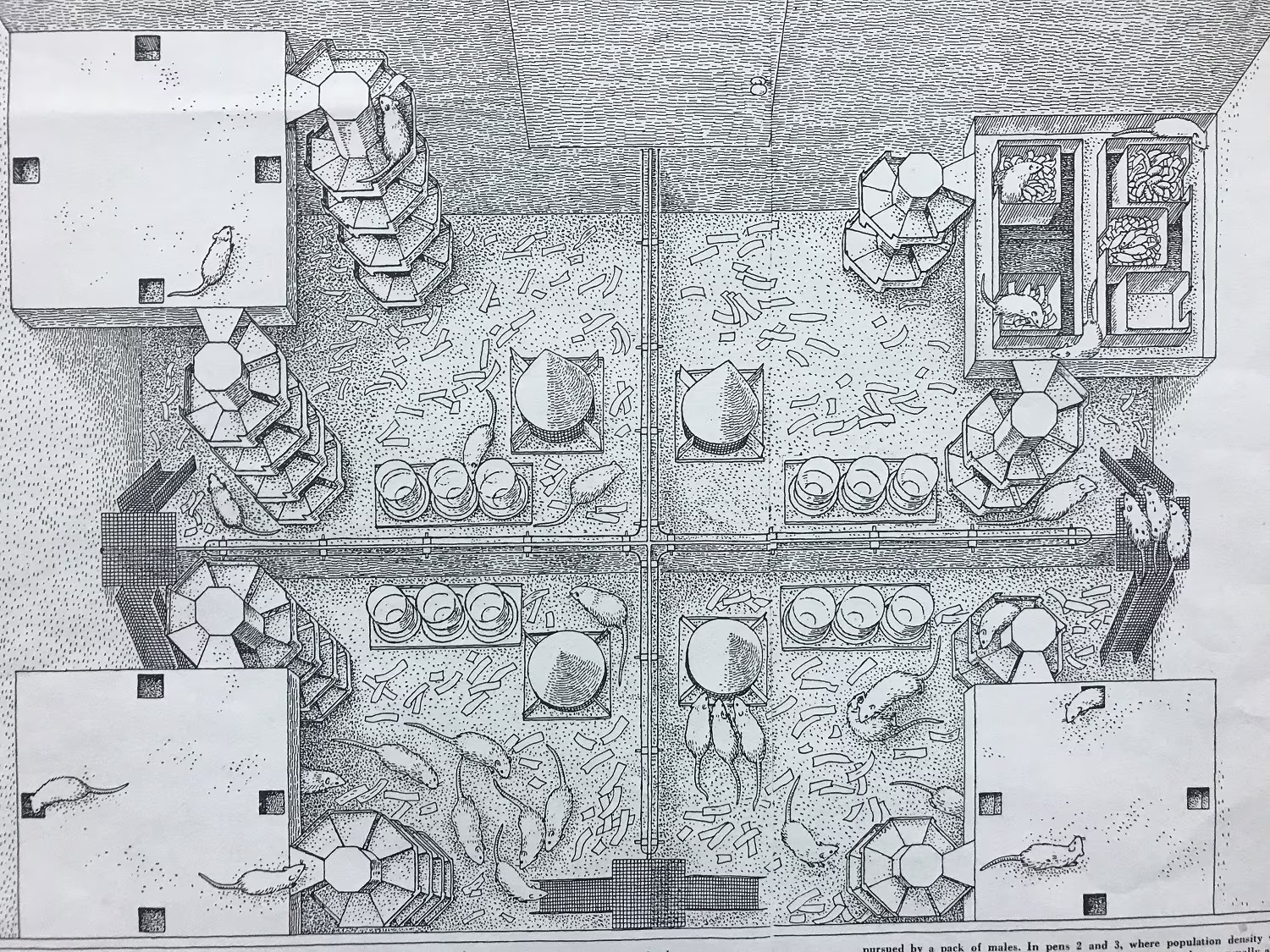

Few studies are able to investigate these questions systematically as it would be extremely unethical to pack hundreds of people into a building and systematically observe how crowding impacted everything from their survival abilities to their social interactions. Therefore, studies have had to focus on other creatures. Most famously, crowding was studied in rats by John Calhoun in what he called his “behavioral sink” studies, but what others have since called the “rat utopia” studies. In this set of studies, Calhoun created a 10 foot x 14 foot enclosure, separated it into four pens, and created ramps so that rats could easily move between the pens, except for pens 1 and 4. Each pen contained a feeder, a water bottle, and an elevated burrow box large enough to comfortably house twelve rats. Four pens with housing for twelve rats each makes the comfortable population capacity of this area 48 rats. He then placed 80 rats into this environment and observed the rat’s behavior. The feeders and water bottles were consistently refilled so that the rats always had enough food and water to maintain life, regardless of how many rats were in the pens. This is why these studies are referred to as “rat utopia” studies. The rats have everything they need to lead full and healthy lives. The only thing that was constrained was physical space.

Across the studies, the rats developed many social issues. The male rats were consistently fighting one another. Some established territories in pens 1 and 4 and guarded those territories fiercely, going so far as to sleep at the bottom of the ramp so that other male rats would not be able to enter the pen the dominant rat had claimed. Female rats stopped building nests while pregnant, had difficulty moving their pups to safe environments, and sometimes abandoned the pups in the pens. Infant mortality in the pens was between 80% and 97%, depending on the study. The rate of female rats dying during birth was also orders of magnitude higher than one would typically see in a natural environment. Other rats chose to avoid their pen-mates as much as possible, waking and moving around only when most of the other rats were asleep. Still other rats (all males) became hypersexual and pansexual, going so far as to chase female rats all around their pens and even into the burrow boxes, which male rats typically never go into. To avoid these hypersexual males, the female rats typically ran into a dominant male’s pen, who would then either fight with the hypersexual male or engage in sexual behavior with him.

Obviously, humans could never be subjected to an experiment like the rat utopia studies. However, humans, like rats, are highly social creatures. Crowding is likely to affect us somehow, even if we don’t know from experiments exactly how we would be affected. There are non-experimental forms of evidence we can use to gain some insight into how humans are impacted by crowding. For instance, if we keep the size of a room constant but add more people to the room, that tends to create negative psychological outcomes for people. There tends to be a jockeying for position and a tendency to defend territory that can result in aggression. This is generally referred to as social density and is often seen in institutions where people are required to be in the space, the requirements for space are always growing, but the locations are not easily expanded. Examples of such places would be public schools, prisons, and in-patient mental health treatment facilities. In all these places, adding people beyond the capacity of the building has shown to have very negative psychological effects on the people occupying that building.

Another type of crowding, spatial density, results from the opposite situation as social density. In spatial density, the number of people remain the same, but people are placed into smaller and smaller locations to increase the density. In these cases, even though the physical density may be the same as in social density, the fact that the people were placed into an entirely new environment with different expectations regarding amount of space and territory available makes people experiencing spatial density far more resilient to the emotional stress caused by high population densities. People can cope with this type of crowding much better and tend to have many fewer problems with aggression, violence, and general stress.

Society. When we start thinking about crowding on a societal level, this is when we begin thinking about words like over-population and concepts like resource use. Thinking about human population and overcrowding at a societal level was most prominently conducted by the British pastor and mathematician Thomas Malthus. Malthus is most widely known for his 1798 essay On the Principle of Populations. This essay makes many well researched and well calculated arguments about populations, the most prominent of which is Malthus’s argument about how populations interact with the food supply.

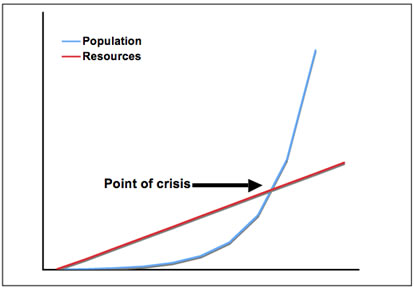

Malthus, Population, and Food: Malthus spent many years modeling the growth of both the human population as he knew it and the ability of that human population to produce food. And from his calculations, he arrived at a surprising and depressing result. He calculated that the population level of any species, with humans being no exception, has the ability to increase geometrically. This means that if you graph it out, the population increase looks like a curved line going up faster and faster and faster as the population grows. This should make sense to us. As more people are born, those people can create even more people. If one person has three children and then each of those children eventually have three children of their own and each of those children have three children of their own, we went from one person in Generation 1 to four total people in Generations 1 and 2 to thirteen people in Generations 1, 2, and 3 and so on. In this way, populations can increase quickly. However, when he compared the possibility of human population growth to how the food supply grows, Malthus encountered a disturbing problem. Using all the available data on grain grown that he had available to him, he observed that the amount of food available to a population can only increase linearly – as in a straight line if graphed out. And the problem occurs when we combine these two graphs. A geometrically increasing population will need a geometrically larger amount of food to sustain itself. But advances in food production did not seem to be moving quickly enough. He predicted that at some point, the human population would no longer be able to produce enough food to sustain itself. When that point was reached, members of the lowest levels of society would be most at risk of starvation as the price of scarce food resources would increase dramatically. He further said that this situation would result in a necessary number of the population dying off to return the population back to a sustainable number.

theory of population.

Malthus in Practice. Malthus’s predictions remained relatively abstract and academic until 1845. This is the year that a potato blight struck Ireland. Potatoes were a staple food crop in Ireland because much of the island’s soil is too rocky to farm grains at a large scale. Potatoes are a very nutrient dense food for the size of farmable land needed, making them an idea crop for Irish farmers. However, in 1845, Irish potato farmers began digging up their crops only to find the edible portions had rotted underground. The potato blight lasted for 8 years and is estimated to have caused 1 million deaths due to starvation and resulted in an additional 2 million people leaving the island and immigrating to other nations – notably a large portion coming to the United States. However, many of the starvation deaths that occurred could have been avoided.

At the time of the potato blight, food was readily available in Ireland. It was simply too expensive for most Irish people to afford. The closest government that can help mitigate the effects of the famine is in England, but many government officials were against directly giving grain to Irish people. However, some were willing to help import American corn into the country to help the starving population ride out the worst parts of the famine. However, Sir Charles Trevelyan, a student of Malthus who was a powerful civil servant within the government advocated against sending American corn to Ireland. He reasoned that sending grain to Ireland would allow the Irish population to become even larger than it already was. Which would simply mean that more food would be needed to feed that larger population. In essence, they feared England would get caught in a loop whereby if they sent food relief to Ireland, then the Irish would make more Irish people, which would require more food to eat which they didn’t have and then England would have to send even more food the next time. Instead, he advocated for the famine to serve as a “natural” check on the population of Ireland.

And though their ideas may have seemed like wisdom when explained this way, I personally find this reasoning to be incredibly cruel. Remember that Ireland was experiencing their lack of food because of an outside force beyond their control. A disease was impacting their usual food crops. Should we have expected that all potatoes forever would be impacted by the blight? English policy advisors at the time like Trevalyan certainly thought the disease would last a very long time. But some potato plants were able to resist the blight. These potatoes became the only ones able to be planted the next year, which increased the proportion of blight resistant potatoes in the population. In addition, potatoes from other areas of the world that were blight resistant were also imported to Ireland to help with this problem. Per capita potato harvests largely returned to pre-famine levels after 8 years, but the damage to Ireland’s population had been done. Millions of people had either starved to death or left Ireland entirely. In fact, so many people were missing or dead that Ireland’s population has not risen above the level it achieved in the 1840s to this day (approx. 8 million in early 1840s compared with approx. 5 million as of 2021). How many people could have been saved from a terrible fate had England simply given excess grain directly to the Irish people in 1847?

Malthus in Modern Times. We now have 225 years of data on how well Malthus’s predictions estimated population levels and food production. We should note two things right away. First, the worst of Malthus’s predictions did not come true. The world’s population continues to increase to this day, yet we do not have widespread famines due to a lack of food production. Second, the reality of population and food production closely matched Malthus’s predictions up until around the 1920s. Throughout the 19th century, advances in medical care, public health, and sanitation lead to ever increasing populations while food scarcities like the Irish Potato Famine and the Famine of 1848 in Europe seemed to increasingly highlight the inability of European farmers to provide food for the population of Europe.

However, the 1920s saw innovations in agriculture that dramatically increased how much food could be grown on an area of land. Some of the most important innovations during this time included the Haber-Bosch process which efficiently converted atmospheric nitrogen into ammonia, which could then be used to produce anhydrous ammonia, an effective fertilizer. Other innovations that improved the food supply were mechanized tractors with internal combustion engines, crop rotation, soil conservation techniques, and refrigeration. These innovations together caused a massive increase in the amount of food grown and preserved, which created the conditions to feed a quickly growing population.

One other innovation was introduced into the U.S. market in 1960 that also impacted how well Malthus’s model predicted population and food conditions. That was the introduction of oral contraceptives in 1960. Oral contraceptives helped to end the baby boom that occurred after the end of World War II and have also dramatically reduced birth rates around the globe. Populations are now growing much slower than would be predicted by a purely geometric model. In fact, many wealthy industrialized countries are now facing the opposite problem. Their populations are now beginning to fall. Notably the populations of China, Japan, Russia, and many other countries in Europe are seeing population reductions – which tend to create labor force problems that often ultimately result in inflation. This is why Hungary is instituting its childcare initiative. They are facing a labor shortage so severe that, by some projections, one out of every four jobs will not have a human in the country to fill it by 2030. This dramatically contrasts with the worst predictions Malthus made regarding populations in 1798. The concerns of the world regarding crowding are much different now than they were in 1798. Technology and innovation have changed the concerns.

Summary

Crowding can be considered from many different perspectives, individuals, groups, and societies. Individual crowding is similar to the concept of interpersonal space while group crowding follows concepts of social density and spatial density with social density tending to cause more psychological problems for the members of the group. Societal level crowding was originally modeled by Malthus, but now is governed by other concerns.

Also called the "rat utopia" studies, a series of studies in which John Calhoun gave rats enough resources to live, but over crowded them to the point they developed abnormal social behavior.

When density and crowding are increased in a space by keeping the size of a room constant and adding more people.

When density and crowding are increased in a space by keeping the number of people in a space constant and reducing the size of the space.

An economic situation in which prices are rising faster than wages. Results in people feeling as though items are more expensive and being less able to purchase goods and services.