7 Justice and cultural sensitivity

Chapter Goals

- Define distributive justice

- Recognize disparities in access to professional jobs and service

- Understand why professional services should not be luxury goods

- Define unfair discrimination

- Understand how tradition can generate unfair discrimination

- Understand the libertarian model of justice

- Understand the consequentialist model of justice

- Understand the egalitarian model of justice

- Understand the need for cultural sensitivity

7.1 Introduction

As a foundation for thinking about justice in the realm of professional services, recall four key points.

- Professions are defined in terms of the basic needs they address, and each profession develops a corresponding body of technical expertise.

- The most desirable professional-client relationship is the fiduciary relationship.

- Professional services are a public good.

- The interests of a client can conflict with the public interest.

These points can generate conflicting duties. An accountant may see that a client’s business has become more profitable because they have reduced their commitment to public safety by illegal means, and this discovery may demand a suspension of client confidentiality. A mental health therapist strives to uphold and increase client autonomy yet may have to abandon those expectations when a client is highly likely to become a serious threat to others. (See Chapter 6, Sections 6.3 and 6.4.)

Conflicts can also arise due to conflicting demands on the distribution of professional resources. This chapter addresses these conflicts through the lens of distributive justice. The focus is fairness in the distribution of benefits and burdens created by social patterns. The primary focus is on access to professional services—and, because services cost money, the distribution and redistribution of wealth. As such, dstributive justice should not be confused with criminal or legal justice.

Unfortunately, almost everyone agrees that professional services are not provided to all who need them in a fair manner. Obviously, high-demand occupations with shortages of qualified workers will tend to have high wages, and the cost for their services will be high. Consequently, many professional services are out of reach for many people. While most people regard this as more or less unfair, a sizeable minority denies that it is unfair. On one common view, there is nothing unfair about restricting services to those who can pay their own way, and nothing unfair about the concentration of professional services in cities, creating “service deserts” in rural areas. Others see these things as profoundly unfair. The second half of this chapter will map out these competing views.

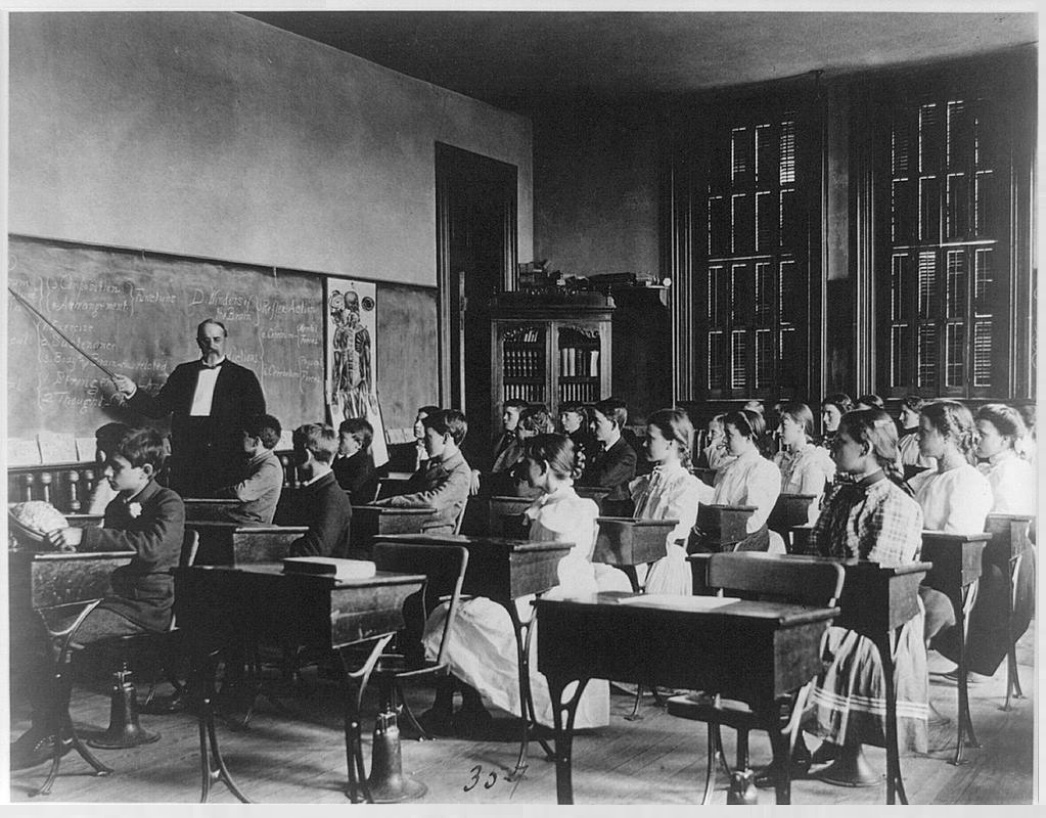

No one denies that the shortage of qualified professionals is a serious ongoing issue. To a large extent, it is an unintended consequence of enforcement of educational standards for entry into the professionals. As explained in earlier chapters, the various professions are defined by their attention to different basic needs (e.g., health care focuses on health). The professions develop technical expertise to address these needs and professional status is restricted to those who acquire this expertise through advanced education. Consequently, social roadblocks and personal missteps at various stages of education combine to limit the pool of future professionals. Even after education is completed, testing and licensing creates a fresh obstacle—most professional testing has unusually high failure rates for college graduates who do not come from middle- and upper-class backgrounds. As a result, the demographic profile of the professions does not mirror the diversity of the population they serve. Again, there is disagreement about whether this creates an unjust system and, if it does, why.

A third issue is generally seen as a matter of concern. As the United States becomes increasingly diverse, the professions are notably lacking in corresponding diversity. Most professionals have no personal knowledge of the issues faced by marginalized groups they will serve. Numerous studies show that most professionals in education and health care provide measurably lower levels of service to clients from traditionally disadvantaged and marginalized communities.

For these and other reasons, the professions have not fulfilled their commitment to provide services to every person who needs their help. As a society, we have a right to expect more from the professions. The difficulty is the lack of agreement about what justice demands in response.

Here are three steps that might be taken to improve things.

- Society might deal with the high cost of services by demanding more pro bono work from professionals. (See Chapter 4, Sections 4.8 and 4.9.)

- Society might put more funding into professional education, removing the education costs that serve as a barrier to becoming a professional.

- Steps might be taken to make employment more attractive in places where professionals tend not to want to live or work.

Does this mean that the government should be more intrusive into professional life? Does it mean that more tax dollars should be directed at providing professional services for low-income clients? Overall, the United States has witnessed declining support for government intervention, with increasing numbers of people adopting a libertarian perspective that regards government intervention as an unjustified expansion of the reach of government. Although rural areas would reap the most benefit from more government intervention to support rural professionals, these areas tend to vote against expansion of government and government-subsidized services.

Another issue is whether the professions have remained sufficiently focused on dealing with basic needs. There is no reason to think that better access to health and legal services means offering every possible medical or legal service to everyone, regardless of ability to pay. Instead, the duty is to address basic needs. (See Chapter 4, Section 4.6.) Each profession has a duty to ensure that everyone gets an appropriate level of service relative to basic needs. The closest we get to reaching this ideal in the United States is free public education. Government mandates in health care have improved access to essential medical care, but only some aspects of health are addressed. For example, dentistry and mental health services are essential services, but the U.S. does a poor job of providing them to large numbers of people who need them. Free legal support is only guaranteed for those charged with a crime who cannot afford a defense lawyer. Yet criminal defense is merely one specialization within the legal profession. Yet people need access to sound legal advice when dealing with many other kinds of legal issues.

Summarizing the main issue, there is no theory of justice that endorses things as they are.

Although they differ, legal justice and distributive justice intertwine. The laws that govern society both reflect and shape social patterns. To consider a common issue, when zoning laws in a town require low density housing on one side of town while allowing high density housing in another part of town, the result is a pattern of segregation by income. Higher income aligns with low density, and low income aligns with higher density. Wealthier people tend to prefer big houses with lots of surrounding space, while economically insecure people tend to be renters who crowd together in apartments. Furthermore, zoning laws frequently locate industries together in one area, and this area is selected so that any escaping pollution will be directed toward lower income neighborhoods while sparing wealthy neighborhoods. In such cases, distributive justice recognizes an injustice created through public policy in the form of zoning laws. Why should social planning favor the wealthy and punish those who are economically less secure?

Similarly, when laws that regulate professions have the effect of directing professional services to some people rather than others, it is appropriate to ask if the resulting distribution is fair.

Few modern industrialized nations have been willing to make the investment to ensure that every citizen has access to a minimum, decent level of the full range professional services. Sweden, Denmark, and Norway come closest. In countries outside of Scandinavia, most professional services are reserved for the middle class and wealthy. It is difficult to avoid the conclusion that prevailing practices are unjust. Unless one says that the professions have no more social responsibility than for-profit businesses, the professions should be evaluated against their pledge to serve the public. As such, “public” must mean all sectors of the public, and so the topic of justice lies at the very heart of professional service.

7.2 Are professional services a luxury good?

Irrelevant facts about a person should not be used by others to make decisions about their opportunities and future. For example, Ruth Bader Ginsburg was so talented that she was the first woman to serve on the Harvard Law Review. Due to her husband’s health issues, she transferred to Columbia Law School, became the first woman to serve on the Columbia Law Review, and graduated in a tie for top standing in the graduating class of 1959. By any objective standard, she was one of the most employable law school graduates of 1959. Unfortunately, the law profession was biased and major legal firms and the U.S. court system both discriminated against women, especially married women. U.S. law did not yet require equal employment opportunities for women. Although the precise number is unknown, her many applications at law firms were ignored and she struggled to remain in the profession. Continuing to find roadblocks to employment after two years as a law clerk, she elected to become a law professor rather than a practicing attorney. Ginsborg is famous, of course, for her later service on the Supreme Court. By that time, she was already famous in legal circles for successfully presenting multiple gender discrimination cases to that court, reducing gender discrimination in U.S. law by showing how frequently it discriminated against men. Ginsborg was treated unfairly in the first half of her career, and dedicated herself to reducing unfair barriers to others.

Reflecting on her story, we can distinguish between two major types of injustice in professional life.

- A profession can be unjust in the selection of entrants into the profession and in the subsequent treatment of some people who become professionals.

- A profession can be unjust in dealing with some people who seek or need professional services.

While Ginsborg’s story illustrates the first type, the main focus of this chapter is the second type of injustice. (But the first type will not be ignored, either.)

Professions exist to address basic human needs, and the professions are supported in their efforts by giving them a favored, protected status. Consequently, professional services are public goods, meaning that everyone should have access to them, and the access of any one person should not reduce access by any other person. Unfortunately professional services are not always handled as public goods. We have professions dedicated to health care and to education, but in contemporary societies these are expensive services. (In part, this is because they are labor-intensive.) Most countries provide government funding for education and health care, but no government can afford to provide them to the full extent that all citizens desire. When they are turned over to private interests that charge clients for service, many people lose access to some or all of the services they need.

In the United States, the professions are often supported by combining government support and private investment, as in the model of health care where non-profit hospitals get tax breaks and receive Medicare payments for patients 65 and older. Public higher education is partially funded by state governments together with federal and state financial aid for students, but they face competition from private colleges that also collect government aid, often at a much higher per-student rate than the public universities. The roughly 40% of higher education students at so-called “private” schools pull a disproportionate share of public funding. In short, these is often no real division between government and private professional services in the American system.

Consider a simple example of how clients are priced out of the market. Dental health is an important aspect of health. However, dentists are specialized professionals whose training is typically longer than, for example, lawyers. When dentists decide where to live to pursue their profession, they tend to select wealthier areas. As a result, rural areas and even whole states experience a shortage of dentists. There are many places where there are simply not enough licensed professionals to provide all the routine, basic dental appointments required by the population. In these places, dental services are rivalrous. If one person gets an appointment for a routine exam, someone else does not get to see a dentist that year. (Notice that this rivalry for services is not a question of the cost of those services. It’s the very availability that is at issue here.)

Where services are rivalrous, that service is not functioning as a true public good. In some manner, it must be rationed. In the United States, the tendency is to let the free market do the rationing. In other words, services are sold on the open market and the price reflects, to a high degree, the economic principle of supply and demand. It says that anything in high demand and short supply will be expensive. By definition, services that address basic needs are high demand services. When they are in short supply, prices rise. (The one major exception is public higher education, were the “flagship” schools and research universities are not allowed to set their own tuition, and so ration access by setting high entrance requirements.) When there is a perennial imbalance of low supply and high demand, the good or service is a luxury good.

Sadly, many professional services have become a luxury good. Where this is the case, the professions may be seen as instruments of injustice. In most of the United States, dentistry is much more like a luxury good than a public good.

Even in places where dentists are plentiful, about 1 in 4 people is unable to pay for a dental appointment. Although the U.S. provides Medicare to cover the health care costs of the elderly and people with certain disabilities, it does not cover routine dental care. As a result, many elderly people will only see a dentist when a true emergency arises. Consequently, many elderly people live with ongoing dental issues.

Contrast this situation with dentists with the following. If someone is charged with a crime but cannot afford a defense lawyer, the United States and many other countries recognizes a right to legal representation, which means free legal services if one cannot afford a defense attorney. In these cases, the government pays a public defender to serve as the person’s defense lawyer. Thus, the majority of those charged wit a crime in the U.S. get a free legal defense. However, 80% of U.S. lawyers specialize in an area other than criminal defense. Although there is a persistent shortage of public defenders, the overwhelming need for legal help is not criminal defense. Many lawyers specialize in family law, corporate law, intellectual property law, immigration law, and tax law. These services are needed by almost everyone at some time, yet people are required to pay out of pocket. Nonetheless, the U.S. only recognizes a right to free legal areas in the limited area of criminal law. The U.S. does not treat other legal services as a basic right. As with dental care, we know that large numbers of people who need legal services are unable to purchase them.

Should the government treat dentistry more like criminal defense? Should the government intervene and pay a special bonus to dentists who will relocate to rural Alabama or West Virginia? Through self-selection, there is also a national shortage of pediatricians, cardiologists, and health providers of geriatric care. Health services for both children and the elderly are hard to get, rivalrous, and rationed. Should medical schools give free tuition to those who specialize in pediatrics, cardiology, and geriatrics in order to increase the supply of doctors in these areas?

In summary, because the professions enjoy a range of government protections, and because this qualifies them as public goods, both the professions and individual professionals should be evaluated from the perspective of justice. Public goods should not be luxury goods, yet the current system renders many professional services into luxury goods.

Architecture affects everyone

Several recent books accuse the profession of architecture of gross injustice. Between them, architects and landscape architects are responsible for the design of much of our “built” environment, most often for their designs of large buildings and public buildings and their landscaped surroundings.

Suppose an architect is hired to design a new building for the business school at a university. In almost all cases, they will begin with the assumption that almost every user of the building will have good eyesight, good hearing, will have the use of their hands, and will be able to walk without assistance. Based on those assumptions, the design of everything from walkways to doors to light switches will follow familiar patterns for that type of building. Accommodations will be made for certain kinds of users: elevators will be large enough for a wheelchair plus a person pushing it, there will small braille markers in the elevator and on some signs, and each classroom will contain a limited number of spots where a wheelchair can park. Parking areas will have some reserved parking spots, and restrooms will have at least one toilet that is wheelchair accessible.

However, slightly more than 15% of the population is disabled as that category is defined in law. This number does not include neurodivergent individuals, such as people with ADHD, autism spectrum disorder (ASD), and sensory processing disorder (SPD). Adding them, we have many people who find the sensory experience of many spaces to be uncomfortable or even unusable. Reliance on fluorescent lighting is a hazard for many people with visual impairments and sensitivity. Priority of the visual elements leads to neglect of auditory design, and much the building will have poor, or even terrible, acoustics. A new business school building is likely to feature entrance spaces and lobbies that are meant to impress, and their open space and hard materials tend to create echoes and harsh sounds that have a negative impact on those with hearing impairment and sensory processing issues. Designs that are favored by architects for their visual power are often designs that have foreseeable consequences of tormenting a portion of the building’s future users.

Granted, there have been improvements in new buildings that are “generally open to the public,” making them somewhat more accessible than they were prior to The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) of 1990. At the same time, these minor changes to traditional architectural design have the effect of dividing most spaces and rooms into two distinct areas: a larger area for “normal” people and an “accommodating” area for those who are treated as “not normal.” Furthermore, the basic design principles for accommodations make many bad assumptions. They assume that no one will have more than one accommodation issue: there will be one grab bar beside an “accessible” toilet, which assumes that anyone using it will have full mobility and strength in the arm that aligns with that grab bar. In Europe, the standard design is a pair of grab bars, but they must be folded down from the wall before using them, so many “accessible” toilets are inaccessible unless the user is accompanied by an assistant who takes care of that task.

More generally, many clients perceive accommodation as an additional expense and are unwilling to consider anything more than the minimum required by building codes and minimums established by lawsuits filed under the Americans with Disabilities Act. The result is that minimally-accommodating buildings are unfriendly (or worse) places for many users. When architects come back later and study user satisfaction for their work, they only get the feedback of people who were successfully accommodated. (They are generally the only ones there to interview.) Thus, the profession often gets a false sense of having succeeded. In the area of retail architecture, there is evidence that some developers of higher-end properties push for as little accommodation as possible. Their reason is not the cost. By providing the bare minimum of accommodation, they actively discourage use by anyone who does not fit the image of an attractive, prosperous consumer. Retail architects often cooperate to please their clients.

7.3 Injustice as unfair discrimination

Most people understand the basic idea of justice, which is that people should be treated fairly. For example, people should be compensated fairly for their work. One unjust practice is “wage theft,” where employers do not pay for part of the time that someone has worked. Another example is that people should not have to deal with discriminatory barriers based on irrelevant factors. For example, same-sex marriage was illegal in most states until 2015. However, the United States Supreme Court then ruled that there was no legal basis for giving various government benefits, such as a special “married filing jointly” tax deduction, to married couples if marriage excluded non-heterosexual couples, thereby giving heterosexual couples a special government subsidy. Why should “traditional” couples get to pay lower taxes? This example points out that there is a gulf between what is fair and what is traditional.

Because traditions are often unfair due to their preservation of longstanding patterns of discrimination, the professions must be on the alert for unfair discrimination preserved as social tradition. This includes the special traditions of the professions themselves. Thus, professionals should be sensitive to two sources of injustice.

- As participants in society, they may replicate injustices that are common in society at large.

- There may be ways their own professions is a sources of additional injustice.

Professionals should avoid unfair and practices whenever possible. For the most part, our concern is with practices that involve unfair discrimination.

At the same time, not every discriminatory practice is unfair. If a mother of two children is disappointed in the career choice made by one of her children—perhaps the child has become manager of a slaughterhouse, and the mother is a committed vegetarian—and she writes a will that leaves everything to the other child, this is discriminatory behavior. However, it is not unfair. The money is hers to do with as she wishes.

The injustice of forced conformity

In 2015, a preschool teacher in Oklahoma made national news for forcing a 4-year-old boy to write using his right hand despite being left-handed. The teacher justified the action on the grounds that being left-handed was “evil” and the work of the devil. While it may be hard to believe this belief is still in circulation and was used as a justification by an educator, it was, for many centuries, standard practice. Left-handed children were forced to copy the dominant group and become right-handed, causing them difficulties for the remainder of their lives.

In other words, we should always be attentive to the harms of forced conformity.

Appeals to “professionalism” and “professional behavior” are frequently used in both business culture and the professions with little understanding that they are appealing to discriminatory standards. They are seldom used to describe the ethical expectations that relate to professional service. Instead, they are a way of indicating that specific social expectations are enforced in professional life. An employee or member of a profession must present themselves in ways that conform to traditional expectations. Judges wear robes in court, and some doctors are expected to wear “scrubs” and lab coats, depending on the setting. But dress codes are only a small part of “professionalism.” In practice, it generally means conforming to relatively narrow standards of behavior and personal presentation. As such, appeals to “professionalism” and “professional behavior” are frequently used to indicate that diversity is “unprofessional,” and these terms can serve as unthinking excuses for discrimination against members of underrepresented and marginalized groups.

For example, although the Civil Rights Act of 1964 prohibits employment discrimination based on race or skin color, it does not prohibit discrimination based on cultural expressions that reflect ancestry and cultural background. There is a prevailing standard that professionals should have neat, tidy hair that does not draw attention. Hair should be in natural colors. Basically, hair standards are highly conservative and reflect the dominant culture. As a result, individuals who come from backgrounds that do not accept these standards frequently find that their hair style can be a barrier to employment and to being taken seriously by other professionals. This problem is especially well-documented for Black professionals, who encounter resistance to braids, Afros, dreadlocks, and other hair styles that are common among Black Americans.

Similar problems arise with speech and writing. The professional expectation of “standard” educated English can be a kind of linguistic racism. It also creates a bias against people with regional dialects and bilingual speakers for whom English is not the primary language. The expectation of a specific mode of grammar and vocabulary and a mid-American accent is frequently directed against speakers of African American Vernacular English; it is well documented that many Black Americans face educational and employment discrimination if they do not become culturally fluent in the kind of English favored by the professional class.

Although these issues are most often studied in relation to Black Americans, they affect many groups. Here are three additional cases where “professional standards” punish cultural diversity:

-

- Long pauses and extended silence is not unusual in the speech patterns of Native Americans and Americans with Scandinavian heritage. However, this cultural pattern can be unpleasant or unnerving for members of other cultural and ethnic groups. Professionals often place a high value on time as a resource and may form negative impressions when professionals from these two traditions slow down conversation or group exchanges with extended pauses when they speak.

- Professionals from the southern United States who leave the South for education and employment often find that they must lose their “Southern” or regional accent to be taken seriously or be accepted as a well-educated professional.

- For the most part, professional scheduling assumes a work calendar inherited from Christian practices. For example, non-emergency professional services are generally closed on Christmas Day. Professionals who seek a parallel accommodation for non-Christian holidays and religious days, such as celebration of the Lunar New Year (so-called “Chinese” new year), can encounter resistance from other professionals in the workplace who see no reason to make allowances for non-Christian traditions.

The remainder of this chapter will explain and contrast three distinct views of injustice in public life—that is, three views defining unfair discrimination. Superficially, the three views agree, because they all say that justice demands fairness, and fairness demands an impartial perspective. A more detailed examination shows that they disagree about what counts as justice in the realm of public services and access to public goods. Although there are more views on the topic than can be covered in an introduction to the topic, these three approaches prevail in modern industrial societies and so they will receive attention.

The three philosophies of distributive justice examined are:

- Libertarian

- Consequentialist

- Egalitarian

7.4 The libertarian model of justice

In one way, the libertarian theory of justice aligns with a major premise of this book, which is that professional ethics should be governed by a commitment to the recognition and promotion of individual autonomy. Granted, not everyone reaches or retains the minimum qualifications for autonomy. But those who possess the basic required capacities should be provided with maximum opportunity to make life choices of their own choosing. In much the same way that the fiduciary relationship is intended to maximize client choice, and paternalism is wrong for not respecting autonomy and free choice, the libertarian model emphasizes that social paternalism restricting choice is unjust.

In the realm of justice, libertarian philosophy essentially says that processes and social arrangements that maximize individual autonomy are fair, but not if they involve involuntary redistribution of resources, even if that is done to help someone else maximize their autonomy. Taxing one person to help another is unfair discrimination against the taxed person in favor of the other. Voluntary private charity is a good thing, but forced participation in charity in the from of government redistribution is unjust.

While there are many elements to libertarian philosophy, the most relevant one in this context is the idea that it is fair—and not unjust—to deny professional services to people with limited income. Support for this view goes as follows. Libertarians will regard a society as having a lesser or greater degree of justice according to the degree that it does or does not interfere with the free pursuit of divergent goals and lifestyles. Different people value different things and different people will make different choices. A system that prioritizes both personal freedom and personal responsibility is therefore likely to have wide economic divisions within society. For example, many people would prefer to work less and earn less, rater than work the 50 to 60 hours per week that is typical of high-earners. Consequently, we should expect to see unequal distributions of wealth and power. Furthermore, libertarians say that a just society does not require individuals to help others they do not choose to help. (At best, they must provide that help only in very special, limited cases.) The fact that many American children are raised in poverty is unfortunate, but it is almost always due to decisions made by their parents and extended family. Using government interventions to educate, feed, and otherwise help these children is an unjust redistribution of wealth. Similarly, the failure of of most people to plan for old age is no reason to have programs such as Social Security and Medicare. These also involve unjust redistribution of wealth.

Consequently, a social arrangement that makes some people wealthy—and who thus have correspondingly more access to expensive professional services—while leaving others in poverty (with correspondingly less access) is not unexpected in a free society, and it is not evidence of injustice.

To put it another way, the ideal of maximum personal autonomy leads libertarian philosophy to embrace small government. At the same time, libertarians recognize that people who harm others reduce the autonomy of those they harm. Therefore, government should play a role in prohibiting and punishing behaviors that directly harm others, either by harming their physical person or by violating their property rights. The other important role for government in interpersonal relationships is enforcement of contracts and prevention of fraudulent transactions. It would be fraud, for example, to offer to sell a bottle of imitation vanilla flavoring labelled as “100% real vanilla extract,” and there is a role for government in running a justice system that punishes fraudulent dealings. With respect to the professions, for example, failure to disclose risks to clients can constitute fraudulent dealings. However, there are no special tasks for government when it comes to the professions. They are simply businesses, like any other business selling a service. There is no important difference between selling professional services and selling cars or donuts.

When it comes to distributive justice, the libertarian model says that market principles should determine distribution of professional services. As such, the government should not license professionals or regulate the buying and selling of professional services. The government should not redistribute income or create incentives to bring services to those who lack resources. For example, libertarians oppose government tax breaks for non-profit organizations. Consequently, our current model of permitting non-profit status when delivering health care and other professional services is a violation of justice. Consider the case of a registered non-profit health clinic. It pays no property taxes (among other things). Therefore, its cost of doing business is much lower than a physician-owned medical clinic that is run as an ordinary business. From a libertarian perspective, the government has created unfair competition by placing more burden on one provider than another.

Libertarians also say that consumers should be free to purchase professional services from anyone who offers them. Our current system of education standards and licensing in health care, law, accounting, and engineering drives up the cost of those services. Government quality standards and enforcement of a fiduciary stance toward clients also drive up the cost of doing business, limiting the ability of newcomers to enter the field. So, the current model of the professions as public goods regulated by government is unfair “big government.” It is unfair discrimination favoring those who have expensive credentials. Furthermore, the prevailing model drives up the cost for clients, because the personal and financial investment needed to become a professional is so high that there is a constant shortage of professionals. This low supply in the face of high demand is yet another factor that escalates the price of professional services.

For libertarians, the proper way to create more access to professional services is to expand the supply, which will drop the price. Expanding the supply requires a reduction in regulations that limit entry into the professions. Fairness requires the removal of government-imposed barriers to becoming a professional. While many professionals will protest that these steps will allow poorly trained individuals to sell professional services, the libertarian model places the task of determining quality on the consumer.

Because the libertarian perspective says that involuntary redistribution of wealth is wrong, they reject the use of tax revenues to support healthcare. Likewise, there is no justification for public schools. It is wrong to require any business or company to hire high-priced accountants to create annual public reports. (People who feel defrauded can sue for damages after the fact.) Finally, the modern field of social work is regarded as an unjust institution that works to undermine the libertarian ideal of small government. Social work should be restricted to private charities.

Obviously, the libertarian theory of justice demands major changes from current practice. Consider health care. Suppose the next deadly pandemic is one in which infected people will need to take doses of turmeric to survive. Hearing an early rumor before the virus arrives in the U.S., an investor buys up all available turmeric in warehouses in the Midwest. The investor pays ten cents per 1,000 milligram capsule. (In stores just before the pandemic arrives, these capsules are selling for about fifteen cents each.) When people realize they need the product and can’t find it, the investor puts bottles of capsules out for auction on eBay. People bid against each other to buy it, and the investor sells the product for $5 per capsule. If this sounds like fiction it is roughly what happened to hand sanitizer in parts of the United States in March 2020. However, that was an illegal activity, and was quickly stopped by the government, and people were punished for it. Libertarians say that government intervention was wrong. This behavior is simply smart business under free market principles, and it is a morally acceptable way to distribute high-demand goods. Libertarians say it was wrong to stop people from selling $3 bottles of hand sanitizer for $100 per bottle, and it would be wrong to stop the investor from selling the turmeric to desperate people at a huge markup.

Likewise, if professional services are a luxury good, that is not unjust unless the supply shortage is caused by government regulations.

To summarize, libertarians say that justice requires repealing the special privileges currently granted to the professions by government. It also demands repeal of legal regulations that are specific to the professions. Generalizing, justice demands removal of any government intervention that interferes with the free market’s determination of a fair price for professional services. The rich may get better services and some poor people will get no services, but that result will be fair and just. Professional organizations will continue to “police” professionals, but professional organizations will be a private enterprise. As such, all professions are likely to operate like the current system of financial advising: a professional organization puts its stamp of quality on Certified Financial Planners who pledge to function as fiduciary advisors, and then everyone else who wants to offer uncertified financial advising is free to do so. It would be left to consumers to investigate the difference and decide whose services they will purchase. (Claiming to be certified when one is not would be fraud, and subject to punishment.) Currently, a range of businesses and organizations are required to hire certified public accountants. Libertarians reject this requirement and would allow the market to determine if anyone wants to pay for certified, rather than uncertified, accountants.

At the same time, libertarian justice does not assume that every exchange of goods or services must be bought and paid for. Voluntary charity is regarded as a virtue. Thus, libertarians endorse social services when they are provided by private charity. If you rightfully possess something of value, you may do with it as you please. Nothing unfair happens if a professional does pro bono work for a friend, charges different hourly rates to different clients who’ve negotiated different contracts for different levels of services, and then rejects several desperate prospective clients because they cannot meet one’s minimum expected fee.

7.5 The consequentialist model of justice

One way to think about libertarian justice is to see it as prioritizing free, unregulated activity. When exchanges of services and goods are not directed by the government and do not proceed through fraud or deception, when they do not involve a violation of property rights of others, when they do not cause any direct harm to anyone, then the social relationship satisfies the demands of justice. Now flip this around and say that unrestricted processes are not a measure of justice. Instead, results are the only criteria for justice, and processes are to be evaluated according to the results they produce. Under consequentialism, a social arrangement or society achieves justice by arranging things in a manner that produces at the maximum best consequences possible, subject to limitations and opportunities generated by the resources available to that society. Regulations are not inherently fair or unfair. Regulations are good, and fair, when they increase benefits and reduce harms.

In identifying justice with processes and social arrangements that maximize good results, consequentialists often endorse rationing. Some people will have to be denied services so that the resources can be directed to those who will get more benefit from them. Given that professional services are in short supply, this approach should be applied to the professions.

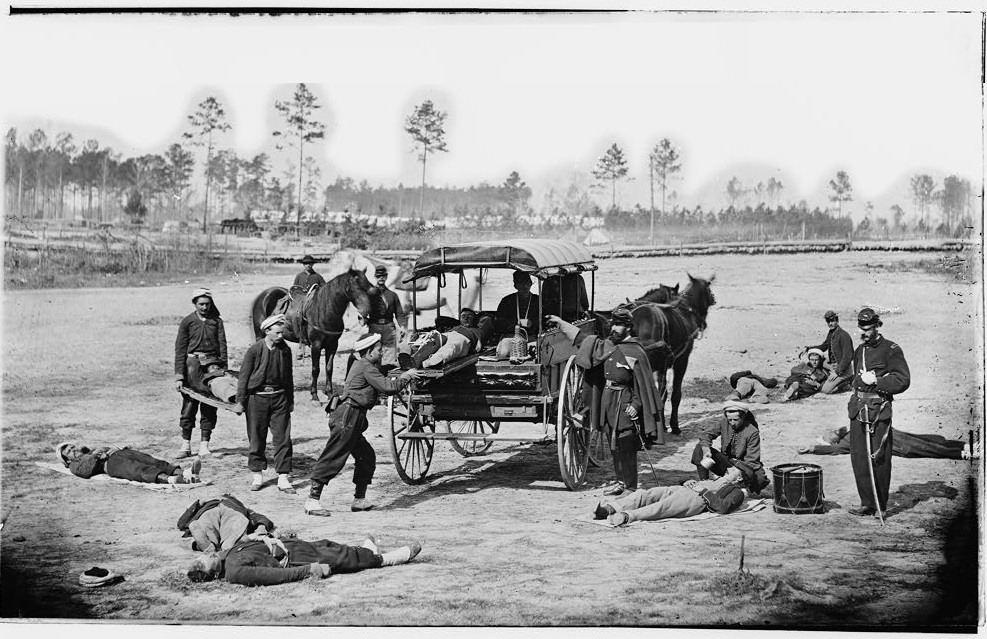

For example, in the field of medicine, consequentialism supports the practice of denying help to some wounded soldiers. This is the doctrine of medical triage. A shortage of surgeons is normal in a combat zone. Time spent with an individual patient is the most precious resource, and it is a limited resource. This shortage of the key resource is managed by providing surgery for those with higher chances of survival. At the same time, care is withdrawn from those who need significant help but are unlikely to recover. A third group of wounded soldiers (hence the word “triage,” for triangulation) is attended by medics who stabilize them in preparation for removal and later treatment. In this way, the limited resource—the immediate care provided by the limited number of surgeons—will produce the greatest number of survivors. Why? The most serious cases will take up the most time, and if the surgeons begin by helping the most serious cases, then surgery will be delayed for any number of less serious cases. But among those less serious cases there will be some who are more likely to survive following immediate surgery, and others who merely need to be stabilized. Therefore, starting off with the most serious cases has the effect of reducing the total good that can be produced with the available resource.

For the consequentialist, it would be unjust to proceed in a manner that reduces the number of people saved. Justice demands maximizing the good outcomes, so justice requires a process of prioritizing some needs over others. Therefore, consequentialist justice requires adoption of whichever criteria of prioritization that produces the best total result. In triage this generally means discriminating against the most seriously injured. Some of the wounded are scarified for the greater good.

Military triage provides consequentialism with a model for addressing the general problem that professional services are always a limited resource. Consequentialism says that justice in the distribution of resources requires whichever distribution has maximum positive impact. Opposing the libertarian ideal of “small government,” consequentialism calls for constant monitoring of outcomes and social intervention to redirect efforts where they will have the best results. (At the same time, micro-management is understood to be counterproductive, because an oversight process requires resources, too, and at some point it becomes inefficient to constantly tinker with the distribution of resources.)

From a consequentialist perspective, social work is the model profession as the professions currently operate. It is generally better to direct our limited resources to prevent a problem from developing than to expend resources to fix it afterwards. This, of course, is one of the guiding principles of social work, the profession that pioneered our understanding of social conditions as the root cause of most crime and health problems. From the start of its professionalization, social work prioritized resources for at-risk children. (See Chapter 1, Section 1.2.) Children are especially susceptible to adverse conditions like abuse, neglect, and poverty. Early intervention reduces long-term negative outcomes, such as mental health issues, substance abuse, and criminal behavior. Similarly, connecting social services to public education can be crucial in determining life-long educational success, which again translates into better lives and fewer social problems. A program of providing free breakfast and lunch for every child in preschool and elementary school has an enormous positive impact. Multiplied across the economy over decades, a small investment in such programs pays economic dividends in a better educated citizenry. Employers are rewarded with greater worker reliability and productivity, as well as more talent in the work pool. There is a corresponding reduction in demand for future social services, criminal justice interventions, and health care.

Pursuing the ideal of professions as social goods, consequentialism does not trust free enterprise to yield justice. For example, Minnesota pays for free breakfast and lunch at every elementary school, public and private alike. Suppose a school district decides to hire one of the available for-profit companies that sells food services to institutions. When creating and delivering a meal, the corporation’s primary goal is making a profit from that meal. The best way to make a profit with mass-produced food is to use the cheapest ingredients and least preparation time possible, thereby maximizing the profit that is extracted from the per-meal price they’ve negotiated. A minimal nutritional profile is set by government regulation, and it is generally more profitable to aim for this minimum than to exceed it. For example, suppose the for-profit company is serving mashed potatoes at lunch. They will use powdered or “instant” mashed potatoes. The process of making them on the premises from scratch is time consuming, and the need to pay for the additional labor cost makes the home-made version far more expensive per serving. As a processed food, the instant version contains fewer vitamins than the same dish prepared on the premises (known as “scratch cooking”), and the instant version contains higher levels of sodium and numerous food additives. Apply this result to all the food served during the average week. Put bluntly, the for-profit business will routinely serve a less nutritious meal than will be delivered by having school-district employees cook all the food from fresh ingredients. Granted, the corporation will have to satisfy minimum requirements. But can we do better? Consequentialism directs us to compare the free-enterprise result with the alternative. Keeping in mind that the schools are providing meals to enhance both student health and the related ability to learn, justice demands healthier food if we can get it for the same cost. Studies conducted over the course of several decades show that school districts that directly hire their own kitchen staff and prepare fresh “scratch” meals routinely provide healthier meals. Yet the cost per meal is roughly the same as for the meals from for-profit companies that compete for institutional contracts. Furthermore, making scratch meals needs a larger staff, so this approach has the added advantage of keeping the state’s money in the local school district, employing local people. Thus, consequentialism says that justice applies to this case because it involves a public good and public funds, and justice favors government-employed kitchen staff rather than free enterprise.

Focusing on results, consequentialism rejects the libertarian’s commitment to private and for-profit businesses. Sometimes private business does a good job, but sometimes it does not. Many public goods require a huge investment and make a limited profit, so they are poorly served by private investors. Since the early 19th century, consequentialists have promoted government intervention to provide public goods that fit this description. Consequentialism supports public schools, public roads, public transportation, public libraries, and government control of such services as water, sewage, and garbage disposal.

In line with other public services and using the consequentialist model, public education used to include free higher education and professional training. For example, in the past many states offered public higher education without charging tuition. This included the University of California system, a group of schools rated as among the world’s best. Anyone meeting the entrance requirements could attend. The cost of textbooks and fees were low. Student loans were rarely needed by anyone attending public higher education. However, this model of public education was overturned in the 1970s. Libertarian-aligned politicians turned against the idea that higher education is a public good. Public higher education started charging tuition. One notable effect of this change is that enrollment in higher education of students from underrepresented populations fell, and then fell again as tuition rates steadily increased. Enrollment from underrepresented groups had been climbing in the wake of Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which eliminated discrimination in college admissions. Charging tuition reversed these gains.

Consequentialists look at the patterns that result from these competing policies and they conclude that it is wrong to treat higher education as an expensive commodity that students must purchase. Consequentialism looks at the before-and-after experiment with American higher education as clear evidence that government investment in public goods is essential to the betterment of society and the advancement of justice. The introduction of tuition in public higher education has made it harder to go to college. It has clearly reduced diversity in higher education. Correspondingly, it has reduced the talent pool in the professions. Students from low-income backgrounds are less likely to seek higher education, and those who do enroll are less likely to finish. (And, of course, those who do not finish cannot join a profession.) For consequentialism, the so-called “neo-liberalism” that privatized public goods and reduced government social services has been a political experiment that failed to produce the benefits promised by its supporters.

Water, consequentialism, medicine, and engineering

Advancing the public welfare often requires the combined efforts of several professions. A famous case from the 19th century brought together medicine and engineering under the banner of consequentialism. In England, consequentialism was popularized by the utilitarian philosophy of Jeremy Bentham. He was among the first to argue that all social arrangements, including all government policy, should be structured to produce the greatest happiness for the greatest number of people. A revised version of Bentham’s philosophy was popularized by John Stuart Mill. The utilitarian version of consequentialism gained popularity as it became clear that private businesses were unwilling to risk the investments needed to solve collective problems.

In the 1840s and 1850s, London, England, became the world’s largest city. London was wracked with waves of deadly cholera, which is an illness caused by a bacterial infection. As cities gained population and became more crowded, cholera regularly sickened and killed people in all the world’s urban centers. Although bacteria had been discovered in the late 17th century, 19th century medicine had not yet confirmed that bacteria cause illnesses. In London, an estimated 10,000 people died of cholera during the extended cholera outbreak of 1853-54. At the time, it was generally believed that little or nothing could be done to stop cholera outbreaks.

However, the doctrine that nothing could be done was proven wrong by the efforts of John Snow, a progressive medical doctor. Snow suspected that cholera was being transmitted in tainted water. He did door-to-door interviewing and mapped the rapid progress of illness and death during a fresh outbreak of cholera in one London neighborhood in 1854. His data established that the outbreak originated from a single location, a water pump near Broad Street. Indoor plumbing and public water service did not exist in major cities of that era. Consequently, cities were strewn with water pumps in open spaces, bringing groundwater to the surface for use by anyone needing it. The water source of the Broad Street pump was very close to a cesspit (sewer pit) that collected the neighborhood’s wastewater. Although no one knew it at the time, the cesspit contaminated the water supply of the Broad Street pump. As a result, if just one person in the area contracted cholera, one trip to the outhouse was enough to spread the bacterium to everyone using the pump. Snow also noted that there was a brewery near the pump, but no one who worked there got cholera. Why not? The workers drank beer rather than water, and the alcohol content was enough to keep them safe. Snow shut down the pump, and the cholera was soon gone from the neighborhood.

Snow also collected data that confirmed the suspicion that wealthier citizens suffered less from cholera. However, his data showed something even more interesting. Families who could afford to buy clean, fresh water had it delivered to their homes in a water wagon. The best quality water was hauled from the Thames River in the west part of London, where the river entered the city. So, this water was fresh and uncontaminated. Snow interviewed homes that bought their water from the “water works” that transported and sold this clean water. These homes were not free of cholera, but the rate was low. He also compiled illness rates for London homes that bought water from a different supplier, who drew their product from the river in central London. This part of the river received substantial runoff from the urban population. Death from cholera was 14 times higher in these homes. The different cholera mortality rates in the two sets of buyers suggested that fresher water did not spread cholera, whereas water acquired further downriver contained some agent that caused cholera. As in Broad Street, the disease was being spread by contaminated water.

Given London’s approach to supplying people with water, a modern reader will see that water was not considered a public good in England at this time. However, Snow was not the first to document the dangers of contaminated water. He was simply providing new and better evidence to supplement medical findings that others had collected for a government report back in 1842. Ironically, Snow’s side-by-side comparison of the two water sources in the Thames was made possible through government intervention based on the 1842 report: the Metropolis Water Act of 1852 had outlawed using or selling water from stagnant and dirtier parts of the river. Snow discovered that the water company that obeyed the law sold safe water, while companies that ignored the law spread cholera. The 1852 law did not prohibit or reduce pollution. It still allowed existing local sewers to empty into the Thames, where human waste mixed with industrial waste and the runoff from slaughterhouses.

Reoccurring cholera outbreaks showed that legal restrictions on the use of river water were ineffective as a public health measure. Neighborhoods with high levels of poverty would continue to use tainted water because the people there could not afford to buy fresh water from a delivery company. They would continue to have cholera outbreaks unless cheap, clean water was brought to their streets and homes. In wealthier areas, for-profit companies were willing to skirt the law to make money, sacrificing public health in the process. Therefore, the solution to the medical problem would have to be public funding of a massive, coordinated engineering project.

The Americans and French were already ahead of the game. New York City built an aqueduct 1842 to supply clean water. Seven years later, the city started work on a comprehensive, integrated sewer project. In France, Paris began work on a comprehensive sewer system in 1850, with an initial plan that involved nearly 400 miles of underground tunnels. In contrast, the English did not nothing about London’s water problem until the summer of 1858, when the Thames River beside the parliament building, the seat of British government, became so polluted that politicians could not bear the smell. Thanks to their own suffering, those with the power to fund a public works solution were finally willing to do so.

Beginning in 1859, the city of London started the digging and urban reconstruction needed for a public sewer and water project. Hydraulic engineers played a major role, reshaping the river itself in central London and mapping out the system that would remove wastewater from the city. Special pumps had to be designed and then installed throughout the city. The core project took 16 years to complete, and then it was gradually expanded into every corner of the city during the rest of the 19th century.

Thus, the solution to the ongoing London public health crisis relied on the expertise of both medicine and engineering.

But the planners also needed to justify taxation on wealthier people to pay for a service that would primarily benefit others. They needed to align it with consequentialism, and so philosophy played a role in the story of how London got city sewers and piped, treated water. At the time, John Stuart Mill was the great popularizer of consequentialist ethics. Because Mill had written extensively in the 1840s on consequentialism and public resources, he was invited to serve as an expert consultant for the Metropolitan Sanitary Association. Mill is famous for the position that the greatest happiness is obtained when government oversight and intervention are balanced against individual liberty. (From today’s perspective, he is a “classical liberal,” more centrist than far left.) Justice demands protection of individual liberty, but it also demands public investment in, and regulation of, public goods that improve the public welfare in cases where these goods cannot be brought to the full population in a profitable way by private businesses. For example, the general welfare is advanced when everyone—or nearly everyone—receives a basic education. However, for-profit education has not found a way to deliver worthwhile education to the poorest families while also making a profit. Therefore, we need public schools. The same applies, Mill concluded, for sewers and water delivery. They demand centralized design and oversight, and the service has the greatest positive impact when delivered free or at a subsidized cost to those who can least afford it. Therefore, it should be a government service. Generalizing, any occupation that lends itself to monopolization should be treated as a public good; therefore, the core professions are, to some extent, public goods and require government oversight and, often, some government funding.

Due to his rising profile on questions of public investment and public oversight, Mill was consulted by the working group that was trying to solve London’s public health crisis concerning water and wastewater. The group hoped he would give public support to their work, and in 1852 he published his thoughts on the issue. Technically, the city of London was only a small portion of greater London. The overall city had no unified government. Instead, each neighborhood or district was self-governing. Knowing that Parliament would never unify these districts under one city government, Mill defended letting each district take control of planning and oversight of the public utility within its district. The British government would take charge of creating and funding the overall project. Local control over implementation in each district would ensure that the preferences of local citizens would be heard by the professionals hired for their part of the project. The engineers would have to work with the people in the neighborhoods. (The model Mill defends is like the American approach to public K-12 education, in which local school districts control the schools in their district.) Rejecting libertarian views of justice, Mill wrote that the principle that “the supply of the physical wants of the community should be left to private agency” did not apply to public goods that must be provided to everyone “at the lowest rates of charge” if they are to be adopted widely, by rich and poor alike. Libertarian principles are good enough if the issue is supplying toilet paper, but not if the issue is supplying clean water and avoiding pollution.

7.6 The egalitarian model of justice

As outlined above, consequentialism justifies some government interventions in the pursuit of justice. Fairness (and thus justice) is achieved by maximizing the benefits gained from any policy or public investment. Clearly, public projects such as sewers and waterworks do this when they improve the sanitary conditions of everyone, without concern for the income or status of the recipients.

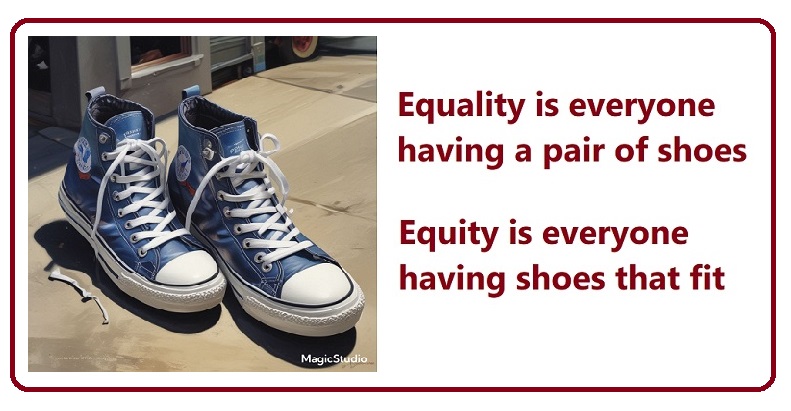

However, the egalitarian theory of justice can also be used to defend public works projects, public education, and similar government programs. Superficially, the two theories look very similar. But where consequentialism asks how much good is produced, the egalitarian asks who gets the major benefit. For the consequentialist, public investment or intervention is justified by the amount of good that it produces, relative to the cost. For the egalitarian, what justifies any public investment or social arrangement is that it specifically improves things for people who were, through no fault of their own, worse off in that area of life.

The egalitarian approach sees public projects such as sewers and clean water as justified by the fact that they do more to improve the lives of the poor and disadvantaged than for the wealthier portion of the population. After all, the wealthy London families who could afford to have water delivered from the clean portion of the Thames did not suffer, and so they gained no great improvement in their quality of life from the public works project they helped fund. (The wealthy merely needed to pay attention and buy water from companies that supplied fresh water.) For egalitarians, this positive result for the least well off is the hallmark of justice.

Let’s contrast the three theories with one example. A relatively small amount of the population benefits from the costly architectural changes demanded by ADA compliance. Libertarians oppose these rules as an unfair burden on property owners. Consequentialism is not clearly in support of these policies, because the small group that benefits might be less than the group that would benefit if, say, the same money was shifted to “green“ architecture and energy efficiency in architectural design. Of the three theories, ADA compliance is most clearly favored by the egalitarian model. With ADA compliance, the benefits go to those who have been disadvantaged by earlier architectural norms. It is not, as consequentialism says, the greatest happiness for the greatest number. Justice in public action is achieved when the greatest positive impact of an intervention or policy is experienced by those most needing help.

An American egalitarian, John Rawls, calls this “the difference principle.” To conform to the demands of justice, any change in social arrangements or change in government policy must do more than make a positive difference. It must make the most difference for those most in need.

However, take care. This does not mean that we can simply identify a fixed group of people as worse off and then take steps to help them. For the egalitarian, worse off does not necessarily mean poverty. People are better or worse off relative to specific social arrangements. Someone can be a professional with a high salary, and so is relatively well off, but as a wheelchair user they qualify as disadvantaged when they try to enter a building that is not ADA compliant. Ruth Bader Ginsburg was a member of the privileged class as she received her law degree from Columbia Law School, but at the same time she was disadvantaged relative to employment in her chosen field. A public school district in rural South Dakota may find that it cannot attract special education teachers. As a result, a child with a reading disorder from a middle-class home may lack proper support and may be worse off, educationally, than a child whose family is classified as living at the poverty line.

The core egalitarian measure of justice is often captured by suggesting that we can think of society as a foot race in which there are winners and losers. However, without intervention and policing, it’s not a fair race. Modern societies have a privileged class, and they (and their children) have a head start. Unless corrections are made, the starting line for most contestants is farther back, so they have farther to run to catch up to society’s privileged class. But it isn’t enough to address the problem by giving everyone the same starting line—a solution often called “leveling the playing field.” Egalitarians note that this looks fair but hides the history of unearned advantages that will still favor a privileged few once the “competition” gets underway.

For a practical application, suppose a public university is going to change its admission policies. For egalitarians, justice is advanced only if the new policy increases enrollment of members of groups excluded by the old policy and by American higher education more generally. Thus, it was unjust for public universities to start charging tuition in the 1970s. The clear result was that those who were least likely to go to college were now even less likely to do so. The compensating solution, loan debt for a majority of college students, was not adequate to restore justice, because this again created more burden for the most burdened. Introducing social changes that make life harder for those who are disadvantaged by current practices is simply unjust. But, again, who counts as disadvantaged is relative to the practice we are examining.

But it is not fair, a libertarian will reply, to force—through involuntary taxation—one group to help another. In reply, egalitarians might refer to the famous saying, “History is written by the victors.” It’s often attributed to British politician Winston Churchill, among others, but versions of this saying have been in circulation since the nineteenth century. The idea is simply that people in power control the history we read, so history books are not an objective story of the past. The history taught in school is basically a justification of present-day power arrangements. For example, the teaching of history in American schools downplays the unethical methods used by the wealthy class and by corporations to gain their current power: the ongoing genocide, forced seizure of property, inhumane treatment of workers, the horrors of slavery. For egalitarians, the libertarian model of justice is an after-the-fact justification of accumulated property and wealth. Libertarianism is a story told by those in power to justify the suffering of those who lack power. It assumes that the “haves” reached their position without violating justice, when in fact most of them were the systematic recipients of unearned privilege. Furthermore, libertarianism is not really an account of justice at all, because there cannot be justice without public support of public goods.

As an opponent of libertarian philosophy, Rawls famously defends egalitarianism by introducing the idea of a veil of ignorance. Suppose the people with the power to set up our social structure and laws had to do so while ignorant about how they would personally fare within the system they design. One might note that Rawls is tapping into a very ancient idea, that “justice is blind,” as in the standard image of Lady Justice as a blindfolded woman holding up a scale.

When the people who control society and its system of justice are not “blind” or veiled about themselves, human self-interest will lead them to describe justice as whatever system favors their current set of advantages. One might see the hand of self-interest in operation in the United States Senate. Almost every senator is a millionaire or better, with a personal fortune that supports a lifestyle that is beyond the reach of the average working American. Why should voters expect these privileged people to understand and support what the average person needs and wants?

The idea of the veil of ignorance is the proposal that those who make the rules should not know if they will reap the major benefits of those rules. Consider this practical example: suppose two children each want the last piece of cake. One child should divide the remaining cake, and the second child should be the one to decide who gets each of the resulting pieces. Obviously, if the one who divides it does not know which piece they will receive, they have an incentive to make the division as equal as possible. Ironically, it sometimes turns out that the privileged class operates with a (temporary) veil of ignorance. They choose to protect their own interests and refuse to help a group in need, only to find themselves later in the group they chose not to help. The English legislature would not tax the middle and upper classes to pay for sewers and clean water as long as they could use their wealth and status to separate themselves from the poor while looking after themselves. They rapidly, collectively reversed their libertarian-leaning policy when “the great stink” arrived at their workplace in 1858 and they found themselves in the ranks of those in need of government help.

Rawls proposes that the ideal of justice is for everyone to have an equal chance to benefit from the social rules and from the decisions made by those who hold power. (Think here of the children dividing tat piece of cake.) But as a practical matter, we cannot always achieve our ideal. Many people would like to live in a house by the ocean with an unspoiled view of their private beach. Some lucky people do. However, most people have no chance of doing so, because the ocean-view property is expensive and the economic deck is stacked against most people from birth, or because of bad luck that befell them—they cannot hold a steady job, a trip to the emergency room bankrupted the family, or they grapple with mental illness in a country that does not provide universal health care. But even if none of these misfortunes happened, we still could not accommodate everyone who would like to live by the ocean. There are simply too many people who want the same limited resource. However, we can compensate: we can require free access to the beaches, and for those who cannot afford a trip to the beach, we can provide public parks and public recreational areas. However, to make this happen, we must engage in some amount of redistribution of wealth, taxing those with greater income in order to address basic needs by funding public goods for those who cannot afford them.

A child of recent immigrants may, through no one’s fault, need extra resources in the public school to become bilingual, becoming a competent speaker, reader and writer of English, the default language. A child who has suffered physical and mental abuse from a violent parent may, through no fault of their own, need mental health services to cope with many situations that do not trouble most people. Or a child might be born with spina bifida, a condition of the spine and nervous system that can require a wheelchair for mobility, and suppose this child is born into a family that cannot afford it. The accident of where one is born is another factor. In many places, gay and lesbian students in the K-12 public schools will experience social isolation and marginalization, if not open discrimination. Depending on where one is born, one’s skin color and perceived ancestry may be either a liability or an unearned benefit.

In a world where some people are already being treated unfairly, egalitarians say that those who are unlucky in life’s lottery deserve equitable support when accessing public goods.

Let us return to the case of higher education. Suppose the government creates equal access to colleges and universities by ending overt discrimination, as was done with the Civil Rights Act of 1964. But suppose the government did nothing else. Groups that are poorly served by underfunded local public schools will be disadvantaged in college applications and in their college studies. Meanwhile, others will be advantaged by having good local schools. Those who get a superior K-12 education are more likely to go to college, and they are more likely to benefit more from their university education. Thus, equal access means that those who started out with an unearned advantage at the K-12 level will get a bonus advantage at the college level. Unearned advantages of childhood multiply as unearned advantages in later life.

In short, justice requires equitable support, which often means more support, rather than equal support.

In many ways, then, social work should not be operating as a separate profession. Every profession should adopt the viewpoint of social work, seeking an equitable distribution society’s public goods. Professional goods should not be luxury goods. Consider the non-profit hospital that operates a spa, offering expensive “wellness” services that are not covered by anyone’s health insurance, and simultaneously pursues payment of emergency room bills from poor families, driving many into bankruptcy. This is not equitable medical care. For egalitarians, the United States is unjust for providing the most expensive health care in the world, and thus the most advantaged people (economically, at least) have the best health. Giving some limited health coverage to poorer Americans is not enough to achieve justice. We need to provide a minimum level of completely free basic health care to poor and otherwise disadvantaged people. Government should address basic health care needs for everyone before providing any advanced medical care to senior citizens: we should not support advanced medical care for anyone until basic medical care is provided to every citizen. An egalitarian argument might also be made that the government should not subsidize employment-related health insurance plans (as the U.S. does now) because these give health care advantages to those who are already advantaged (those with full time employment).

7.7 Cultural sensitivity

The introduction to this chapter noted the relative lack of diversity in the backgrounds of people who become professionals, and suggested that this is a reason for concern. The problem extends to how professionals treat their clients. Childhood culture and its traditions shape the beliefs and values of almost everyone. A disproportionate number of professionals come from a background in a European-derived dominant culture. Yet just under half of all Americans identify primarily with other, non-European cultural traditions. As a result, many professionals do not understand the viewpoints or value systems of many of their clients. Unfortunately, some professionals find it difficult to respect a client’s beliefs and values when they diverge from the dominant culture. Yet the client’s position may be typical of their community or cultural background.

One reason to be concerned is that professionals cannot win the trust and cooperation of their clients unless they respect their values. Ideally, this means being nonjudgmental and working to uphold each client’s values. In practice, this translates into a prima facie duty not to be paternalistic by substituting the professional’s values for those embraced by the client.

However, the professional duty not to push one’s own values onto clients can produce an ethical conflict. What should professionals do when a client has values that directly conflict with those that govern the professions?

Although the professions strive to uphold client autonomy, the European-American model of individual autonomy is not universally embraced. Some cultures either downplay it or reject it. Consequently, cases arise where a client is an adult of sound mind who wants their parents or another relative to assume the client’s role in the fiduciary relationship. In effect, the professional is being asked to facilitate paternalism and to support a social relationship that conflicts with contemporary professional standards. To many professionals, some cultural patterns endorse a family dynamic that can look like coercion and manipulation. The professional may think the right way forward is to encourage “personal growth” in which the client ignores family pressure and cultural expectations. This is especially likely to happen when the client seems unhappy about family and other third-party expectations. Many professionals become frustrated when the client’s community pushes them to reject options that the professional recognizes as aligned with the client’s best interests. For example, an oncologist may have a cancer patient who clearly wishes to cancel further treatments after several rounds of chemotherapy have produced painful mouth sores, nausea, and neuropathy without addressing the cancer. Yet the patient then schedules more chemotherapy because their family pushes it. What is the right approach to these cases?

Again, it is important to grant that it is normal for a client to endorse the values that were presented to them in their childhood upbringing. In most cases, they have internalized and adopted values of an established cultural tradition. They identify strongly with these values, and many clients will experience any challenge to these values as a personal attack. Next, combine this point with the fact that many cultures reject the idea of personal autonomy. Instead, they value group harmony, respect for hierarchy, and collective decision-making. They may place a very high priority on respect for elders. A client raised with these values is likely to struggle with the view that they have a right to pursue their own individual goals and live as they think best for themselves. Recall the discussion of autonomy in Chapter 4 (Section 4.2), which stressed that autonomy is not automatic. Functional autonomy requires self-recognition of one’s personal agency and self-governance. An individual’s degree of autonomy depends on developing various capacities. Autonomous decision making cannot suddenly be imposed on someone who has never been allowed to make personal choices about important aspects of their own life and who sees no value in doing so. When a professional tries to establish a fiduciary relationship with such a client, the client is likely to reject the fiduciary model of professional life.

Many American professionals find this dynamic to be troubling, but it is quite normal in many of the world’s major cultural traditions.