5 Informed consent and conflict of interest

Chapter Goals

- Define informed consent

- Understand informed consent as a complex process

- Define duty of disclosure

- Address common mistaken assumptions about informed consent

- Understand the “average, reasonable” person test and its application

- Understand how lies display a lack of respect for client autonomy

- Define therapeutic privilege

- Understand the limits on claiming therapeutic privilege

- Define conflict of interest

- Understand conflict of interest in multiple professions

- Understand how to proceed if conflict of interest is unavoidable

- Define nepotism

- Understand why nepotism is a serious issue

5.1 Two examples

In February 2024, parents of junior high school students in Quebec Province, Canada, accused a teacher, Mario Perron, of exploiting their children. The parents notified the school that drawings produced by their children under his direction in art class were being offered for sale on the Internet without their permission.

Perron sold his own art by using personal pages on a website for independent artists. However, parents learned that one of the pages of the site was called “Creepy Portrait Art” and it featured nearly one hundred images that were not by Perron. Instead, they were created by students he taught at Westwood Junior High School. The images included heads with devil horns, faces covered with jagged scars, faces with gouged-out eyes, and people with skulls instead of faces. One image showed a relatively normal looking young man, but behind him the room was in flames. Another image showed a person waiving a butcher knife. Perron got the students to make the “creepy” art by showing them artworks of Jean-Michel Basquiat and telling the students to create portraits of a similar kind: both self-portraits and ones of other students in the class.

Parents were disturbed to see that the images were labeled with their children’s first names, such as “Olivia’s Creepy Portrait” and “Jackson’s Creepy Portrait.” The pictures remained on the Internet without their creator’s permission even after the school board began an investigation of Perron’s behavior.

Here is a second case that might seem unrelated.

In 2020, the Ontario Association of Architects gave a finding of professional misconduct for Francesco Di Sarra, a licensed architect in Ontario Province, Canada. Designing a home for a client, Di Sarra and the client arrived at a design that featured custom-made millwork, that is, wooden molding and trim work that would be unique rather than purchased ready-made from a commercial seller. Di Sarra provided architectural drawings to the client, who then put them out for bid by local firms that did custom millwork. The firm of Capoferro Inc. provided a bid, but the client was never informed that Di Sarra owned Capoferro.

Why should the client care about it? Because it was possible that the architect had created a design where he himself was in the best position to furnish the millwork. The Ontario Association of Architects found that Di Sarra had hidden a conflict of interest, that is, he’d provided professional advice, but the advice opened the door to personal advantage and financial gain. Because Di Sarra never disclosed that he was also a millwork maker and would try to supply his own products to the client, it was reasonable to question the motives behind Di Sarra’s plan for expensive custom millwork in the building’s design.

The common element in the two cases is that the professional failed to secure informed consent before taking action that a client might reject if the client had known more about it. Specifically, each of these two professionals failed to reveal the possibility that their relationship with the client was being manipulated to increase the professional’s income rather than to benefit the client. Thus, the lack of informed consent was coupled with a conflict of interest.

Both the duty to get informed consent and the duty to avoid conflict of interest are policies adopted under the more general fiduciary duty of doing what is best for the client. They are policies that safeguard client autonomy. (In the case of the junior high students, the parents should have been informed and offered the opportunity to refuse.)

The first part of this chapter reviews the basics of informed consent. It then examines the problem of conflict of interest, including the special case of personal relationships between clients and professionals.

5.2 Informed consent

Informed consent is a prima facie duty for professionals who are in a fiduciary relationship with a client. Basically, it requires professionals to ensure that individuals understand their alternatives when dealing with a problem. This includes understanding the potential risks and benefits of various alternatives. (Here, risk means a possible bad outcome.) Informed consent requires clear communication between the client and professional. In practice, informed consent should be understood as a process that aims at ensuring that client decisions are voluntary and free from coercion or manipulation. The process might lead to the client”s decision to do nothing.

The two key elements of informed consent are disclosure of appropriate information and confirmation that there is adequate client comprehension of the information. Both must be secured before a professional asks a client to decide how to proceed to address their needs.

This duty of disclosure is not present when the relationship is justifiably paternalism or agency. (See Chapter 1 for explanations of these alternative relationships.) When a college instructor paternalistically selects a textbook for a course because they judge it to be appropriate, they do not owe an explanation to the students who take the course. Similarly, suppose a structural engineer is hired to retrofit an older house, making it more secure during earthquakes by bolting the house frame to the foundation. If it is a standard approach and the client tells the engineer to use their own judgment about the details while staying within the established budget, then the client has consented to an agency relationship from that point forward. The professional has no need to tell the client why a specific brand of bolts is selected, or to inform the client of the benefits and risks associated with bolts of various sizes and quality grades.

There are three major misunderstandings of the process:

- Many people wrongly think that it requires the professional to provide a client with every possible option.

- Many people wrongly think that it requires the professional to explain every possible risk.

- Many people wrongly think that each professional must share the same information with each client facing the same problem. It is also a mistake to think there is a fixed script the professional must follow.

As with so much else that happens in a fiduciary relationship, the background idea is that professionals should treat their clients as autonomous individuals. Conducted properly, the consultation process helps the client to become more autonomous—more fully in control of their own life. Therefore, whenever a client has sufficient mental capacity and other prerequisites for independent thought and action, the centerpiece of the fiduciary relationship is the aim of having the client understand the source and scope of their problem and the viable solutions that are consistent with the client’s goals, values, and preferences. After that, the client should be the one who chooses what happens to address their needs.

Again, it must be emphasized that informed consent includes the client’s right to reject all the alternatives offered to them. No matter how desperate the situation, every competent client has the right to refuse further action if the client rejects the proposed solutions.

Autonomy assumes that people vary in their preferences and values, and they have a corresponding right to live a life that differs from other people. People also differ with respect to memory, attention, and speed of comprehension. They differ in their preferred language and favored communication styles, in the level of education they bring to the discussion, and in their prior experience with the professional field and its services. Talking to a poorly educated client by using the language professionals use when talking to one another is a recipe for failure of comprehension. The professional has a duty to work with the client where the client is, that is, to “translate” their own technical expertise into language that the specific client can understand.

For example, a structural engineer might simplify information when explaining the need for foundation reinforcement to the owner of a large office building. Instead of using technical jargon, the engineer could say: “The foundation needs extra support to prevent cracks and shifting over time. We’ll add steel beams and concrete to strengthen it, ensuring it remains stable and safe.” This explanation avoids technical terms like “load-bearing capacity” or “shear stress,” focusing instead on the practical outcomes and benefits, making it easier for the client to understand the necessity and process of the reinforcement.

Here is a second example. An accountant might talk about “inflow,” “outflow,” and “assessment of liquidity ratios” when talking to an experienced business owner who has a Master of Business Administration degree. But suppose the accountant is having a first meeting with a cook who has just started a first business. The business involves selling corn dogs and grilled cheese sandwiches from a food truck. The conversation may sound very different. The accountant will make the same points, but will talk about money coming in, money going out, and setting a budget for daily cash on hand. Furthermore, the amount of detail given to this second client might be far less than with the first client. If the accountant sees that the food truck owner is struggling to understand the basics of accounting principles, the professional may decide to start with a handful of priority issues while leaving further topics for later conversations. Issues that do not require an immediate decision can be discussed later, and gradually. This approach avoids overwhelming a less knowledgeable client with too much information.

As these examples suggest, knowing how much to say, and how to say it, is one of the most important skills that professionals bring to their role as advisors of clients. Sadly, effective communication skills are too often treated as a “soft skill” in professional development, leaving many professionals less than effective in fulfilling a central responsibility.

By extension, it should be obvious that the process of achieving informed consent must be carried out in language that the client can understand. In a multilingual community, for example, medical professionals and some legal professionals and social workers have a duty to provide translation services. Other professions generally do not have the same level of emergency need and therefore can place the burden on the client to provide their own translation services.

Because professionals know so much more about their area of expertise than anyone outside the profession, it cannot be the case that they must share everything they know with each client. The idea of “full disclosure” is a misleading, outdated description of the duty to disclose. As a practical matter, full disclosure is impossible. If there were any such duty, doctors could just hand the Physician’s Desk Reference and a stack of medical textbooks to their medical patients, tell them to read all the relevant pages, and come back later to discuss it. But, of course, many medical problems need to be addressed quickly, and there simply isn’t time to cover everything there might be of some possible interest to the client. This is why Chapter 1 stressed the duty to interview each client and to accurately assess the client’s situation and needs, allowing the professional to then focus on the most appropriate alternatives and the most relevant information about possible outcomes.

Because professionals tailor their advice to the individual client, the procedure generates frequent complaints and lawsuits from unhappy clients who do not like the outcome despite their informed consent. Professionals should be aware that unhappy clients will often claim that there was no informed consent, on the grounds that the professional did not provide sufficient information about possible bad outcomes. This is the reason why many professionals require a client’s signature on a document outlining what the professional will (and will not) provide in their services for that client. In other cases, such as the syllabus a college instructor issues to students at the start of the new term, no signature is collected. Yet the document serves the same function. Although not foolproof, both signed and unsigned documents offer some protection should the client later claim that there was no process for informed consent.

5.3 The “average, reasonable” person test

So, what is the minimum that a professional should tell a client? That is, what precisely must be disclosed under the duty of disclosure?

The basic standard for American professionals was established by Judge Spotswood Robinson III. It is provided as part of his ruling in the 1972 case Canterbury v. Spence (409 U.S. 1064, 93 S. Ct. 560, 34 L. Ed. 2d 518, U.S. Nov. 1, 1972). Jerry Canterbury sued a neurosurgeon, Dr. Spence, alleging that Spence had talked him into a procedure for back problems without explaining the risk of paralysis as an outcome of the recommended surgery. Because Canterbury was a minor at the time, Spence did not discuss the details and risks with the patient, but instead scheduled the surgery after discussing it by telephone with his mother. She later testified that Dr. Spence told her that the surgery posed no special risks. When Spence operated on the patient, he discovered that the diagnosis of a ruptured disc was incorrect. There was no ruptured disc. Spence then did a different procedure that he thought appropriate to the real problem, a swollen spinal cord. Following the surgery, the hospital staff left Canterbury unattended for long periods, and he fell when he tried to get out of bed to use the toilet. Within hours, he developed paralysis in his legs from which he never fully recovered.

Ruling in favor of Canterbury’s lawsuit and upholding an award of damages, Judge Robinson laid down a crucial test for informed consent: the reasonable person test. Which risks would an ordinary, reasonable person of average intelligence want to know about? Those are the risks that a professional has a duty to share with any client for the consent to count as informed consent, shifting responsibility for the outcome of the decision to the client. Since the mother had not received this degree of advising from Spence, her consent to her son’s surgery was not informed consent.

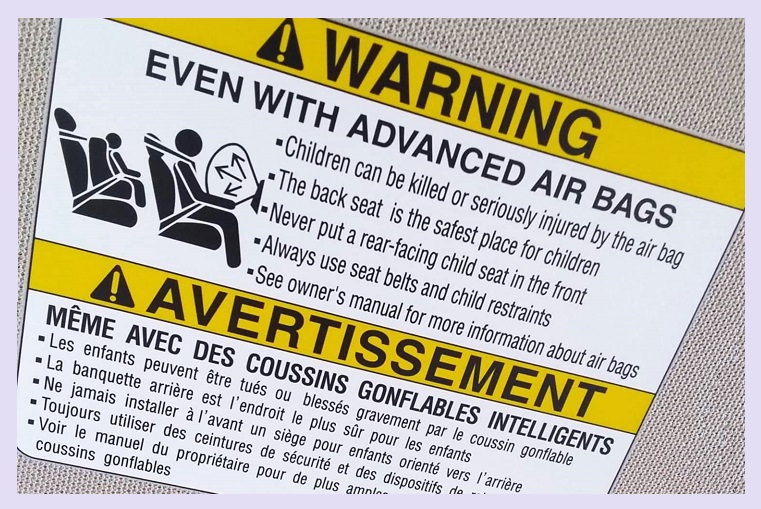

The ”average, reasonable” person test requires the professional to disclose anything that the average person would find “significant” in reaching a decision. A potential disability is significant, even if the risk of it happening is low. At the same time, the duty to warn cannot require the professional to discuss every possible risk, for then the client is likely to be overwhelmed by the information. Some clients will become unreasonable frightened by hearing about how many things might go wrong. To draw a line between significant and insignificant information, Robinson proposed that professionals do not have to discuss things that the average person could already be expected to know, nor to discuss “hazards” and risks that the client already knows about.

For example, anyone entering a hospital at the height of the Covid-19 pandemic in late 2020 must have known that hospitals were full of patients with the respiratory infection, and also that being there put them at high risk of contracting the coronavirus. Therefore, at that time there was no duty for an emergency room physician to warn someone being treated for a broken leg that they might be exposed to the virus in the emergency room. (It is likely that they simply demanded that everyone entering would mask up, without wasting time on an explanation.) Similarly, an engineer would have no reason to tell a client that the construction industry has faced the problem of counterfeit bolts and fasteners for more than 40 years. These cheap counterfeits do not meet quality standards, and there is always a remote possibility that some of them could make their way into the client’s project, reducing its strength. But there is always a possibility that unscrupulous people will sell fraudulent projects, and every reasonable person should already know this.

The Robinson ruling established the basic standard for disclosure for medical care. But it extends far beyond medical care. It has become the standard for all professional-client fiduciary relationships. (In fact, Robinson made the explicit point that the duty of disclosure is essential to the fiduciary relationship.)

For example, real estate agents are expected to disclose known structural defects, past water damage to the property, and planned development that might impact the use and value of the property. Fiduciary financial planners are required to warn clients that stocks and mutual funds are, by definition, high-risk investments. They are not like money in an insured savings account, and putting all one’s money into them as investments can lead to a loss of some or all of the investment. On the other hand, a financial planner does not have to have the same level of discussion about this risk with an experienced investor that they would have to provide to a first-time investor.

Many people continue to associate informed consent with the medical field, especially the practice of having a patient sign a form that summarizes what they’ve consented for the physician or medical team to do for or to them. However, the key point here is that every professional in a fiduciary position has a duty to secure informed consent before taking action for the client. Having the client put a signature on a piece of paper is not itself informed consent. It is, instead, a piece of legal evidence that there has been communication between the professional and the client. It is a document that says that a genuine conversation has taken place, and the client has been told about (and understands!) the risks, benefits, and alternatives. In other cases, the signature merely confirms that additional information has been supplied to the client, providing technical details of policies that are not considered significant enough for to the decision to require verbal disclosure. For instance, medical patients are often advised in writing that they must honor all hospital policies, but then leaves it to the client to educate themselves on visiting hours, nondiscrimination policies, rules governing facility use, and so on.In yet others, the signature confirms that the client was offered an opportunity for discussion, but declined. (This method is common when filling a prescription at a pharmacy.)

A Legal Loophole

A loophole is an error or ambiguity in a law or rule that permits someone to violate its purpose without actually breaking the law. Telehealth companies, which provide selected medical care without an in-person medical visit, have found a loophole in American regulations concerning pharmaceuticals. When drug manufacturers advertise their products to the general public, they are required to present a “balanced” picture of the benefits and risks that are associated with any drug they advertise. However, it never occurred to lawmakers that telehealth firms would try to boost profits by pitching specific drugs to consumers on social media. As a result, telehealth companies target individuals in social media ads and posts, encouraging people to take specific drugs without explaining the associated risks.

Because the telehealth companies are independent of the manufacturers, the law says that requirements to explain a drug’s risk do not apply. Technically, the ads and social media posts are advertising the telehealth medical facility, urging the consumer to use their online process to be screened remotely for a prescription, which is then followed by a direct sale of the drug, which is then shipped to the consumer. (There is an additional element to the loophole: one company employs the doctor and a second company sends the drug, but both companies are owned by the same people. In most places, it is an illegal conflict of interest for a doctor to prescribe you something and then profit from selling it to you, so shady telehealth marketers set up two companies to get around the law. The consumer experiences a seamless move from the physician to the sales team.)

Despite the technical loophole, what is really happening is that a supplier is working to get consumers to select a specific product without first undertaking the process that is expected for informed consent. By the time the consumer talks to a physician, the consumer has decided to buy the product and so the physician-client relationship functions as an agency relationship. The physician’s role is reduced to a legal step in selling, rather than a genuine advisor.

The results can be dangerous. For example, ketamine is used in medical facilities as an anesthesia during surgery. Despite it not being approved for other purposes, it has become increasingly popular both for self-treatment of some mental health issues and for its effects in recreational drug use—and, sometimes, as a sedative used in sexual assaults. As a controlled substance, it requires a prescription. The American telehealth industry expanded rapidly during the coronavirus pandemic, when laws were relaxed, permitting telehealth to be used for treatment of anxiety and depression. Within a few months, one South Carolina doctor prescribed ketamine remotely to more than 3,000 people, which suggests that minimal time was spent with each one before the doctor issued a prescription.

Following the success of remotely prescribing ketamine, telehealth companies have aggressively expanded their advertising. Soon, they paid social media influencers to praise their products on TikTok and other platforms. As a result, people with no medical background are praising drugs without explaining their risks, then providing a link to a telehealth firm that is giving financial support to the influencer. For example, in 2024 there was a sudden spike in sales of the drug Zofran, a powerful drug that reduces nausea and blocks vomiting. Telehealth firms used influencers to recommend it to pregnant women as a cure for morning sickness, as well as to people with a stomach “flu.” None of them informed their audience that the drug is intended for people in chemotherapy, or that its common side effects include pounding heartbeats, diarrhea, hives, dizziness, gut pain, and mental confusion. Because the influencer is not a licensed professional and does not claim to be one, they are not required to reveal these side effects when they urge viewers to connect to their telehealth “partner.”

In short, telehealth firms have found a loophole that lets them advertise controlled substances without clearly telling consumers why they might regret using them. Although they offer compressed summary of the risks just prior to finalizing the prescription, the companies have buried this warning at a late stage in a process that manipulates people to purchase the product—generally for purposes other than its approved use—before they learn anything about its potential harms. From the perspective of professional ethics, any medical professional who profits from this approach is violating their fiduciary duty by using a loophole to shortcut the normal process of informed consent.

5.4 Telling lies

If it is wrong to withhold relevant information from clients, then it is likewise wrong for a professional to lie to a client. However, it is important to see that lying is closely related to a second behavior, lying by omission: withholding information with the intention of deceiving someone.

As with other duties, the duty of honesty is a prima facie duty rather than an absolute duty. Professionals sometimes find that a situation with a client leads to a conflict between two duties, and therefore there may be times when this conflict should be resolved with either a lie or with something less than full honesty.

Suppose an accountant takes on a new client, a pest control business, but soon finds that the business has no documentation of the cost of disposing of leftover pesticides or pesticide containers. However, these are routine costs in pest extermination businesses. The accountant suspects that the business owner is ignoring pesticide containment regulations and is illegally dumping the containers and unused pesticides. The accountant asks about the lack of receipts for payments for the disposal of the hazardous waste, but the business owner says, “I’ve got a deal with someone to handle that for free,” and will say no more. Based on a duty to protect the public, the accountant contacts the state’s office of the Environmental Protection Agency and reports the situation. (The decision to reveal business operations will be discussed from another angle in Chapter 6, as whistleblowing.) The next time they meet, the client asks the accountant, “Are there any issues we need to discuss?” Because the accountant does not want to alert that client that there is an ongoing EPA investigation, the answer is, “No, everything seems routine so far.”

An honest answer would give the client an opportunity to hide evidence of wrongdoing, undercutting the accountant’s effort to protect the public. Here, then, the direct lie to the client seems justified as the lesser of two evils.

Moving beyond the goal of protecting the public, what else could justify dishonesty? Can a lie to a client be justified under the concept of a professional’s fiduciary duty to act in the client’s best interests? The remainder of the section will focus on that possibility.

The core of the issue relates to informed consent. Because clients have a right to understand their situation and options, and professionals have a corresponding duty to put them in a position to give informed consent (or, alternatively, to do nothing), then introduction of lies into the conversation will almost certainly result in a disruption of informed consent. Suppose a client goes to the pharmacy to fill a new prescription. It is for a calcium channel blocker used to treat high blood pressure. The patient asks the pharmacist whether there are any things to avoid while taking the medication, and the pharmacist says, “No. None at all.”

Let’s assume that the pharmacist is competent. The issue here is neither honest mistakes nor professional ignorance (i.e., a failure to know what one is supposed to know). If the pharmacist is competent, they must know that this patient should avoid grapefruit and grapefruit juice, because these neutralize calcium channel blockers. If the patient were to have grapefruit regularly, the result could be the same as not taking the medication, with potentially life-threatening consequences. But suppose the pharmacist is very busy and wants the conversation to be over as quickly as possible, assumes that the patient is like most people and seldom has grapefruit, and simplifies things by telling the lie.

To classify a statement as a lie, at least three things must normally hold:

- The speaker believes that something is factually the case.

- The speaker communicates that the opposite is true.

- The speaker does this to get someone else to believe that the opposite is true.

Our pharmacist lied to shorten the conversation, where the step of producing the client’s false belief was undertaken to create a false sense of security that would (hopefully) end the conversation.

Obviously, this lie is wrong because it puts the client at a risk of harm. But that is not the fundamental problem here. A professional might tell a lie that poses no threat of harm to the client, and it would still be wrong.

For instance, some fiduciary financial planners are art advisors. Original fine art is a common investment for wealthy clients, and some financial planners have special expertise about the topic of buying art as an investment. Some investment firms even have teams specializing in art wealth management. Suppose a financial planner on such a team has a client who has a personal preference for paintings of clowns, and has told the financial advisor to be on the lookout for them. At first, the professional follows these instructions, but it soon becomes clear that this client’s investment preference is leading them to fall short of their financial goals. The professional stops telling the client about available clown paintings and drawings, urging investment in a broader category, such as circus drawings by the 19th-century French artist Henri De Toulouse Lautrec. The client eventually goes along with this advice. As the expert expected, the works by Touluse Lautrec steadily gain value. However, the client regularly asks, “Any clowns for sale?” Although the art advisor is aware of some, they lie, saying, “Not that I’ve come across.”

The financial advisor has lied for the good of the client. Given that the professional has a duty to pursue the client’s interests, isn’t it acceptable to resolve the moral conflict between this duty and the duty of honesty by rejecting honesty?

Some people will point to the practical issue: what if the professional gets caught? This could lead to a loss of trust for this client, and it could feed a more general loss of trust in the profession. While that is a reason not to lie, it involves a calculated risk. The professional might decide it is a risk worth taking, which is likely true of almost everyone who lies. So that is not a very strong reason not to lie.

A more important reason is that the lie reduces the client’s autonomy. Knowing the facts, the client might still prefer to buy clown paintings, accepting a reduced gain on investment because the client will get personal satisfaction from owning a bunch of clown art. The financial planner prioritizes financial gain, but the client wants to balance this against another personal value. It is not the professional’s business to get the client to align their priorities with those of the professional. It’s the other way around: unless doing so will harm others, professionals must aim to provide alternatives that align with the client’s own values and goals. Telling a lie to a client to benefit the client shows a lack of respect for the client. It is a form of disrespectful manipulation.

A similar conclusion holds for deception by omission, that is, leading someone to a false conclusion by saying something true, but also saying less than the whole truth. Suppose the client asks, “Any clowns for sale?” The financial planner answers, “You know they don’t come on the market all that often.” This response may be true, but it avoids answering the question. In this context, it implies that there are none available without saying that there are none. So, there’s no lie. Yet it also a manipulative response that shows a lack of respect for the client.

5.5 Therapeutic privilege

There is a special situation that can justify a lie or a lie of omission, and that is the case of therapeutic privilege. It is mainly relevant in the health services. According to the doctrine of therapeutic privilege, information can be distorted or withheld from a client if learning the information is likely to cause severe harm to the client. Normally, this is understood to mean that the client is so emotionally damaged or unstable that the professional believes they will be psychologically damaged by the truth. Obviously, this decision is always problematic. It shifts the client-professional relationship to paternalism, and it does so without the client’s consent to this paternalism. (Some countries have criminalized therapeutic privilege as an illegal violation of professional duty.)

A plausible example of justifiable therapeutic privilege would be an elderly patient who has developed dementia and has been placed in an assisted living facility. If the patient cannot understand their condition (a common problem in cases of dementia), they may ask repeatedly why they are being held in a facility. Why can’t they leave and go home? At first, the staff tries to explain the patient’s situation to them, but the patient becomes visibly upset. They have to be restrained when they throw themselves against a locked door. But then the patient asks again the next day, and the staff realizes that the patient does not remember the conversation from day to day. Answering the patient’s question with an honest answer does no good and merely upsets the patient, interfering with care. Soon, the staff responds to the patient’s question by saying, “You fell at home and hit your head, and you’re just here overnight so we can observe you.” This answer satisfies the patient until they forget it, and then they ask again and get the same lie repeated to them.

This lie is told to avoid ongoing psychological harm to the patient. However, it involves a patient who lacks the full mental capacity for autonomy. So it is not a situation in which the duty of informed consent applies. That duty is owed to the patient’s guardian.

The question, then, is whether there are cases where therapeutic privilege is justified for a competent person who is not judged to have a diminished capacity for decision making.

One plausible case would be a situation where there are multiple issues and the professional risks overwhelming the client by disclosing too much information. The professional might be justified in deciding to “divide and conquer” the issues, focusing on the most important issue and saying nothing about some others.

For example, a financial advisor meets with a new client for the first time and reviews their existing investment portfolio. The client has three issues: a high concentration in a single stock, an unbalanced asset allocation, and outdated beneficiary designations on retirement accounts. Recognizing that addressing all these at once might overwhelm the client, the advisor focuses on the most critical issue first: the high concentration in one stock. The advisor explains that this poses a significant risk to the client’s financial stability, especially if the stock’s value plummets. By spending their limited time together on just this one issue, the advisor aims to protect the client’s portfolio from immediate volatility. Once they have worked through this first issue, the advisor plans to explain the other issues at a meeting scheduled for the next month.

Or consider the case of a student who has just transferred from a religiously affiliated college to a state university. In terms of credits completed, the student has sophomore standing. The student has decided to switch from their previous major of political science to a major in business administration. Reviewing their transcript, the student’s new advisor sees two major issues. First, the previous college structured its general education program around courses in general humanities, and only two such courses can be counted as general education courses in the state university system. The student is woefully behind in taking general education courses, and there will be limited time to do so while pursuing a business administration major. Second, the student did not take calculus or statistics, and both are required to move forward in coursework for the business administration degree. The student also needs the university’s one-year sequence of introductory courses in economics. The student’s courses for their first two semesters are basically locked into place if the student plans to pursue this major. Seeing this, the advisor provides a fixed set of courses that will fill the student’s schedule for two semesters, and says, “Take these classes in the fall and spring. We’ll address your path through general education once we see how you do with your fall classes.” The advisor intends to recommend general education summer courses during their next meeting, in October, but says nothing more due to a concern that the student might be overwhelmed. After all, the student can see the problem for themselves in the degree audit form that the student brought to the advising session.

Be careful, however. Don’t confuse creating benefit with avoiding harm! Positive impact on a 3rd party is generally irrelevant. For example, a college teacher has a popular course that fills quickly. Another teacher in the same subject knows that the first teacher will let in one student as a favor, but only one per semester. Suppose that a student who has this second teacher as an advisor asks if there’s any chance to get in the popular course, and the advisor says, “You’ll have to go ask yourself.” The advisor does not disclose their power to get the student into the class. The teacher wants to use the favor for another student, a student with a higher GPA who has been waiting two semesters to get into the course. While this behavior will benefit the student with the higher GPA, and while this might be better all around, that is not an acceptable reason to give a less-than-honest answer to the one who asked. This lack of honesty creates benefits for someone else (the student with the higher GPA, who is a 3rd party in the situation where the first student asks the question). However, this lie of omission does not prevent any harm to the student who asked. The key criterion that is generally accepted as a basis for non-disclosure or a lie of omission is the need to avoid significant harm to the client who would normally receive the information.

Summary: basic guidelines for suspension of duty to inform and therapeutic privilege

There are some basic guidelines for when a professional can insert a paternalistic intervention in what is otherwise a fiduciary relationship.

1. A professional can intervene or take action on behalf of a client without permission when the client or client’s guardian cannot be informed in time, and action must be taken because there is imminent risk of serious harm to the client or the client’s interests. (For example, it is a medical emergency with very high probability of very great harm. The most common example would be medical treatment for an unconscious person in a medical emergency.)

2. The professional can intervene and take action without the client’s permission when disclosure would create a strong emotional response that would be psychologically damaging to the client. (In other words, suspend the process of informing the client if there is a very high probability that the information in the disclosure would create a risk of serious harm, either indirectly or directly.)

(Note that these two exceptions cover cases involving suspension of the process, rather than justification of partial disclosure that will be followed by additional disclosure until a later date.)

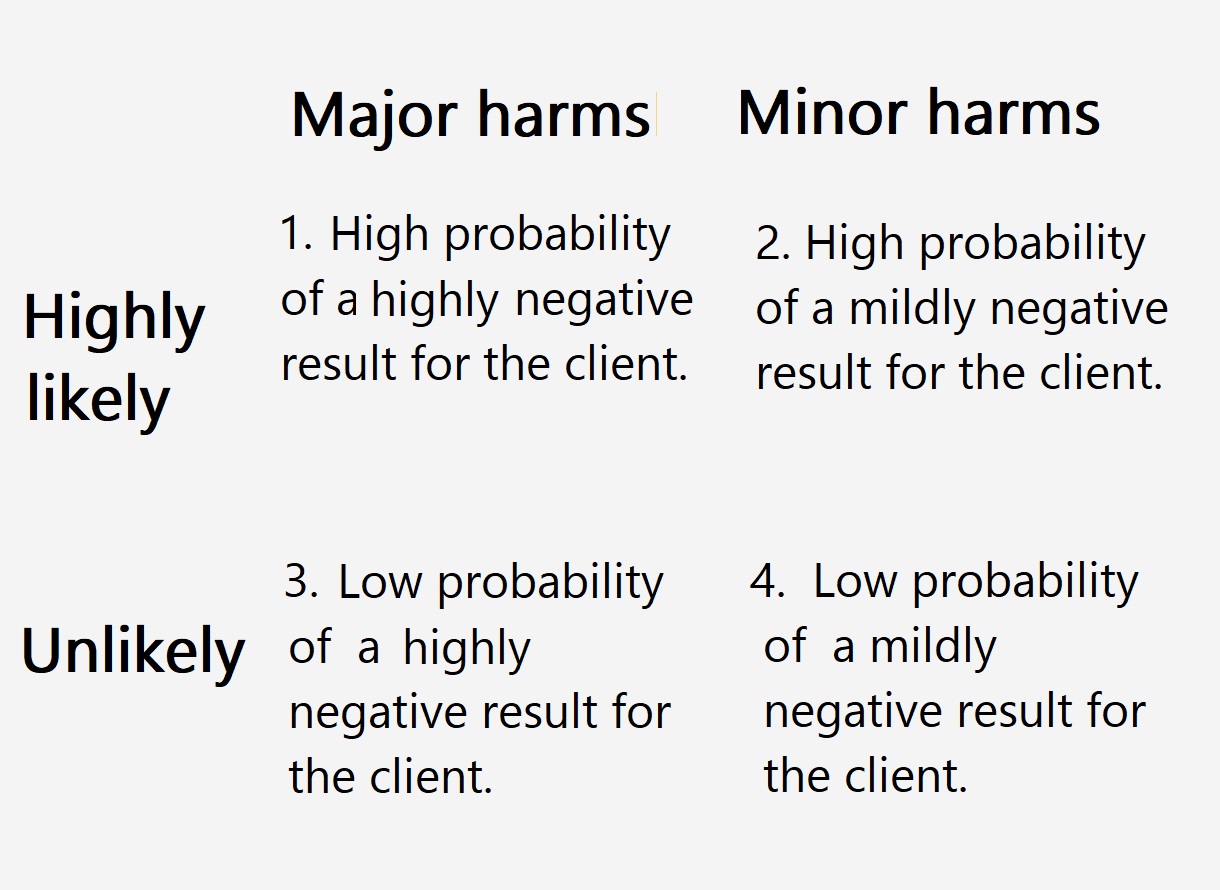

In applying these two exceptions, it is important to that they hinge on two variables:

1. The level of impact from disclosing the information, from little impact to highly negative impact. (Since disclosure is always a process, the amount of time needed for disclosure is relevant to this calculation of impact. For example, waiting for an unconscious patient to regain consciousness would be evaluated under this variable. )

2. The probability of any given impact, from low to high.

Both of these variables require assigning a rating, from low to high, and the duty to get informed consent should be waived only in cases where both variables receive very high scores.

In the simplest terms, assume that every communication with a client has negative consequences of either high or low impact, and each impact has either high or low probability. As such, the process of taking time to get informed consent can be evaluated according to the resulting placement in this grid:

In order to be morally justified in abandoning the process of informed consent, either the process of disclosing the information or the information itself would have to generate the situation identified in box #1 (i.e., very high probability of a highly negative impact to the client or client’s interests). No other analysis justifies abandonment of informed consent with a competent adult client.

5.6 Conflict of interest

A conflict of interest in professional life is present when personal interests or relationships are in conflict with, or might interfere with, professional duties and responsibilities. Many organizations have policies and procedures in place to identify, disclose, and address conflicts of interest. At the same time, some of the policies that are commonly enforced may set minimum standards that are too low.

As with so many other duties that hold in professional life, managing conflicts of interest is essential for maintaining trust and integrity. Professionals should avoid even the appearance of a conflict of interest. But, as has been said before, the public relations value of avoiding these conflicts is not the primary reason to see a problem with conflict of interest. The core problem is that these conflicts undercut client autonomy and the fiduciary duty to prioritize each client’s best interest.

Conflicts of interest can take many forms. As suggested earlier in this chapter, some of them will encourage a professional to withhold important information from clients, adding deception to the core problem. Clients and supervisors have a right to know if a professional has a potential conflict of interest that could compromise their professional judgment. Professionals who are employees of businesses or organizations should always report any potential conflict of interest to their supervisor.

Here are the most common types of conflict of interest.

- Dual roles: In contemporary professional life, professionals are most often employees, and many are employees of a business that seeks to make a profit from their activities. The goal of making a profit frequently clashes with the goal of providing appropriate levels of service, as when the profit-motive leads the business to schedule more clients than they should. As noted earlier, this problem can also arise with non-profit organizations.

- Financial interests: Some professionals work for themselves as small business owners or have a partnership in the business. This is frequently true in the fields of accounting, law, and health services. As such, professionals often have a conflict of interest when their own personal finances depend on the financial success of their business. Besides business ownership and partnerships, this can include ownership of stocks, or other financial arrangements. A health professional who has invested heavily in a specific pharmaceutical company might be more likely to advise clients to use its products even if that is not the best choice for the client.

- Dual employment: Engaging in dual employment can create a conflict because the responsibilities and goals associated with one employer can conflict with those of another. For example, doing work for a competitor or taking on freelance projects can directly compete with one’s existing employer.

- Gifts and favors: Accepting gifts, favors, or other benefits from clients, suppliers, or other stakeholders may create a conflict of interest. These can be seen as attempts to influence decisions or compromise objectivity. Most professions adopt the rule that professionals should not accept any gifts of more than trivial value, such as a cup of coffee, and should not accept any discounts or favors that are not equally available to the public.

- Personal relationships: If a professional has personal relationships with colleagues, clients, or other individuals that could affect their ability to make impartial decisions, it constitutes a conflict of interest. This can include family members, close friends, or romantic partners.

To make better sense of this topic, here are three professions, showing how conflict of interest may play out in very different ways.

Health Care

Not feeling well, someone goes to the local walk-in clinic. An hour of waiting is followed by fifteen minutes of consultation, at the end of which the examining physician says, “Lets do a blood panel to see what might be going on.” In other words, the doctor recommends a spectrum of blood tests. But who owns the clinical diagnostics laboratory where the blood samples are analyzed? Few doctors will offer options about this step in the process. Yet many physicians are either owners or co-owners of the diagnostic laboratory they use, and they directly profit from every test sent to that lab. Basically, this practice amounts to undisclosed self-referral. Studies suggest that a physician who owns or co-owns their own lab orders up to twice as many lab tests per patient as ones who do not have any such financial incentive. It is difficult to see how owning a clinical diagnostic lab is not a financial conflict of interest. The owner-doctor who orders a high number of lab test might sincerely believe that all of the tests are justified, but self-deception is not uncommon when people explore their own motivations. As Upton Sinclair famously noted, it is difficult to get someone to understand something, when financial interest depends on their not understanding it.

The conflict of self-referral is considered so serious that it is, in some cases, prohibited by law. However, this is another case where the law does not align very well with ethics. American law only prohibits self-referral of lab work when the patient is using government-supplied health care insurance, and even then, doctors are allowed to use their own lab if it is in the same building as their practice.

Many patients with good health insurance might not care about the manipulation inherent in lab self-referral. They are likely to pay the same co-pay whether there is one test or five from the blood that’s drawn. However, the evidence implies that self-referral drives up the general cost of health care. For poorer patients who lack good health insurance, any practice that increases the cost of service—such as paying for extra blood tests—results in discrimination that disproportionately affects low-income individuals and marginalized communities.

Education

Teachers face a range of scenarios that generate conflict of interest.

- Favoritism: Preferential treatment to certain students is a conflict of interest. A teacher’s positive or negative feelings about a student can affect grading and other aspects of the student-teacher relationship.

- Financial interests: If a teacher has a financial stake in a particular educational product, service, or institution, it may compromise their ability to provide unbiased guidance or recommendations to students. In higher education, a professor might receive royalty payments by requiring students to purchase a textbook they have written and published with a textbook publisher.

- Personal relationships erode impartiality: Teachers may face conflicts of interest if they have close personal relationships with students, their families, or colleagues. This can impact their ability to make fair and impartial decisions.

- Dual employment or compensation: Engaging in outside employment that directly conflicts with the teacher’s professional duties or responsibilities can be a conflict of interest. For example, some companies that produce educational materials pay instructors a consulting fee for evaluating its materials, but to qualify as an evaluator the teacher must first use the materials in a class, requiring the students to purchase the materials.

- Dual roles: In some cases, teachers may hold additional roles within a school or educational institution, such as being a coach, club advisor, or administrator. Balancing these roles without compromising fairness and objectivity can be challenging. A teacher who coaches the football team may be tempted to give an unearned passing grade to a failing student to keep them eligible for the season.

- Accepting gifts or favors: Teachers should be cautious about accepting gifts, favors, or other benefits from students, parents, or other individuals that could influence their decisions or create the appearance of impropriety.

Accounting

The issues noted for health care and teaching also arise for accounting. Let’s go directly to a detailed example of a conflict of interest in accounting involving an audit firm and its client.

Suppose Melpomene Audit Services is engaged to perform an annual audit for ABC Corporation, a publicly traded company. In part, annual audits are conducted as part of the duty to promote the public good. Both investors and customers have a right to know if a company is financially stable before they do business with it or invest in it.

Next, suppose that key members of the audit team at Melpomene Audit Services hold substantial investments in ABC Corporation. Several senior auditors and partners at Melpomene Audit Services have personal investment portfolios that include a significant number of shares in ABC Corporation. This creates a potential conflict between their financial interests and their professional obligations as auditors. The conflict becomes more pronounced when the audit team is responsible for assessing the accuracy and fairness of ABC Corporation’s financial statements, which will influence the confidence of investors and stakeholders in the company’s financial health. Similarly, it could affect their assessments of ABC’s competitors, should they audit them.

Suppose the auditors come across financial problems at ABC. If they honestly report them, the value of their investments may fall, and they will take a personal financial loss for doing their professional duty. On the other hand, if they quickly pull their investments from ABC upon discovering the financial issues, then they are acting on “insider” information that will be not available to the public until the audit is complete. This response would give them an unfair advantage as investors. Furthermore, it may again encourage them to produce a dishonest audit that is too favorable about ABC, because they would have a strong motive to hide evidence that they dumped their stock ahead of the bad news.

5.7 Personal relationships

Personal relationships merit special attention.

In the spring of 2024, a major legal case was put on hold in Georgia. The criminal case involved former president Trump, and the serious charge was racketeering—working with others to interfere with government processes in Georgia in an attempt to declare Trump the winner of that state’s presidential electors in 2020. Trump’s attorneys alleged that the legal proceeding was tainted by a conflict of interest created by Fulton County District Attorney Fani Willis. The attorneys asked that Willis be removed from the case, a move that would seriously disrupt or delay it. The charge? The conflict of interest was that Willis had hired her romantic partner as a prosecutor to work on the case. Willis soon confirmed that she was in a “personal relationship” with prosecutor Nathan J. Wade, but they both said their relationship developed only after he was hired. They denied claims that he was hired because of an existing personal connection.

Why would this matter? Part of the charge against Willis was that she and Wade had vacationed together, and Wade paid for the trips. If true, the value of the trips could be interpreted as “payback” for hiring him. Thus, Willis would have personally profited from the criminal case she had brought against Trump. In short, she was accused of using her professional status for financial gain beyond her salary.

Judge Scott McAfee of Fulton County Superior Court evaluated the charges made by Trump’s lawyers. After reviewing evidence and hearing witnesses, McAffee ruled that there was no proof of conflict of interest: the relationship might have started after Wade was hired and Willis might have paid her share of the vacation trips, as she claimed. Thus, the evidence did not establish a conflict of interest in which Willis was motivated by personal gain to hire Wade. However, McAffee ruled that the pair acted unprofessionally and showed a “tremendous lapse in judgment” with an “appearance” of ethics violations. As a result, either Wade or Willis was required to leave the case. Wade resigned a few hours after the judge released his ruling.

This case is merits consideration because the Trump connection made it into international news. For our purposes, two other things are important. Willis was found to be in the wrong because she should have known better than to have a relationship that created an “appearance” of conflict, a situation that could reduce public trust in the court system. Second, the core of the case focused on a specific way that a personal relationship could taint professional behavior. When a professional gains financially from a personal relationship, they are likely to make decisions that keep the relationship going and the money flowing, even if doing so is not best for their client. (Here, the client is the citizens of Fulton County.)

Setting the financial aspect to one side, there is another reason to think that the relationship was a conflict of interest. Wade worked under the direction of Willis, so they were not equals in the workplace. Willis was Wade’s supervisor in their professional work. The relationship would make it more difficult for her to treat Wade with the same objectivity that she brought to the other workers she supervised. She might go easy on Wade, overlooking poor work performance, to the detriment of the case. (In fact, something like this was alleged about their relationship. Several legal professionals said that they didn’t think Wade was qualified for the job Willis gave him.) If the relationship started after Wade was hired, then it is possible that their unequal status in the workplace resulted in coercion, with the subordinate party likely to go along with the relationship for fear of upsetting or angering their supervisor.

This issue of coercion is taken very seriously in most professional settings. “Romantic” relationships between professionals and clients are forbidden. (Sometimes, the term “intimate” is used to characterize the problematic relationships.) The ban on such relationships is especially strict in counseling and education. These professions are more centrally involved in developing clients’ personal autonomy than, say, health care or accounting. In other words, there is a presumption that the client is a person with less autonomy than the professional. Therefore, any relationship that starts after they meet in a professional setting is unlikely to be a relationship between equals. The student might enter the relationship only because they feel they have no choice or are subtly coerced by the teacher’s authority. Or the student may feel pressured to enter or stay in the relationship out of fear of negative academic consequences if they refuse. Or they may hope for preferential treatment. Consequently, a teacher who initiates a romantic or intimate relationship with a student invites a charge a of harassment or discrimination due to the significant power imbalance inherent in their roles.

These points apply equally to the fields of counseling and social work and, to a lesser degree, to all other professional settings. Where the relationship pre-exists the client-professional relationship, the standard advice is to recuse and refer. (See chapter 4.) If that is not possible, the professional is expected to conduct the professional service under the close supervision of a second professional.

5.8 Nepotism

Parallel concerns arise when the relationship is a family relationship.

Nepotism is the most common issue. It is a workplace practice that favors relatives or friends in hiring, promotions, or other professional opportunities. Traditionally, it was encouraged. Most obviously, it was standard practice when occupations were owned and passed down within families. But it was not confined to those situations. Many large firms and organizations used family and community in recruitment and hiring practices. They frequently justified the practice on the grounds that family and community members would “police” each other. (It was assumed that poor work from one would bring shame and embarrassment to others in the group.) It was also valued on the grounds of workplace cohesion. Employees would have similar backgrounds, and this lack of diversity was thought to eliminate workplace conflicts that might arise from social and ethnic differences and conflicts.

Famously, nepotism resulted in Irish-American domination of several urban police departments in the U.S. from the 19th through the 20th century. The pattern was set in New York City, which founded a public police service in 1844. In the late 19th century, the majority of the employees of the New York Police Department had Irish surnames, and fully a third of the force had been born in Ireland and brought to the United States by family with the promise of a job in the NYPD.

On the negative side, nepotism undermines meritocracy, that is, hiring based on merit. Nepotism leads to unqualified individuals in key positions, because personnel decisions give priority to family relationships rather than skills and performance. Consequently, it generates resentment among employees and job applicants who do not have the same advantages. It also stifles diversity and contributes to workplace injustice. Historians note that when it was Irish dominated, the NYPD tended to protect Irish criminal gangs while enforcing the law in relation to other ethnic groups.

Nepotism became far less common following passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, particularly Title VII, which prohibits employment discrimination based on race, color, religion, sex, or national origin. A prohibition of discrimination includes prohibition of favoritism, so favoring relatives and members of one’s own ethnic group or ancestral group is a violation of Title VII. To encourage workplace diversity and fight segregation, the law makes it illegal to favor relatives or friends over more qualified candidates. (The law does allow for an exception for small businesses in order to allow nepotism in family businesses.)

Besides bringing about greater diversity in the workplace, Title VII made people more aware of the downside of nepotism. This is especially true of the professions. Because they are based on expertise involved advanced education and training, placement and advancement in a profession should be based on merit. Furthermore, a diverse population is better served by diversity in the professions themselves. Since nepotism favors family and social ties over merit, and favors homogeneity over diversity, it is not acceptable in professional life in a diverse society.

The problem is not confined to hiring and employment. It also arises when both people in a professional-client relationship are related as family or close friends. Setting to one side the financial conflicts discussed in the preceding section, there are other reasons professionals should avoid having family members and friends as clients. Professionals are likely to struggle to provide impartial advice or make unbiased decisions, compromising the quality of their services. In addition, it is likely to blur the lines of privacy, making it difficult to maintain the strict confidentiality expected in the professions. (See Chapter 6.)

Consequently, several professions prohibit having a family member as a client. Attorneys are often prohibited from representing immediate family members (such as spouses, parents, children) in divorce proceedings, child custody disputes, or other family law matters. They are generally prohibited from representing family members in estate planning matters and lawsuits over inheritance. They are generally prohibited from representing family members who’ve been charged with a crime, because the attorney might be needed as a witness. Similar issues arise in financial planning and counseling.

Despite the importance of rules that prohibit having a family member as a client, it is sometimes unavoidable.

For example, educational therapists deal with learning disabilities such as dyslexia, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), and various forms of learning anxiety. Suppose an educational therapist living in a small town in rural mid-America has two children in the public school system. It is the only public school within fifty miles, and both of her children attend the school where she works. The younger child is struggling in first grade, and the evidence points toward dyslexia. She is the only specialist in the school district. The nearby private school does not have a specialist. Even if it did, it would be an unfair burden to expect her to remove her child from the public school and pay tuition. Here, the educational therapist must accept the conflict of interest of working with her own child. She might elect to do so privately, at home, in order not to “rob” time from other children needing her assistance. However, even if she makes that sacrifice, she should inform the child’s teacher of her plan, as well as her supervisor, the school principal.

5.9 Chapter Summary

The purpose of informed consent has less to do with protecting professionals in dispute with unhappy clients and more to do with respect for client autonomy. It is especially important for clients to understand risks associated with options they consider. At the same time, there cannot be a duty to inform clients of every risk, both because it is impractical and because it can overwhelm clients. To find the right balance, the professions use the “average, reasonable” person standard. What would such a person regard as relevant? Honesty is another duty required by respect for client autonomy. Yet here, again, there may be situations where the full truth is not appropriate. Finally, informed consent and the duty of honesty are both violated if there is an undisclosed conflict of interest. Financial gain is not the only type of conflict of interest. Personal and family relationships can also generate serious conflicts of interest.