4 Upholding client autonomy

Chapter Goals

- Define autonomy

- Understand that autonomy develops over time

- Understand the core limitations on the exercise of autonomy

- Understand the reason for universal free public education

- Review obstacles to an autonomy-based model of education

- Define academic freedom

- Outline reasons why professionals refuse their services

- Understand the doctrine of recusal and referral

- Define pro bono service

- Understand controversies related to pro bono service

4.1 The Core idea of Autonomy

Chapter 2 stressed that the fiduciary model of professional-client interaction is based on the idea that clients are autonomous individuals and should be treated with the kind of respect that comes with that status. Many of the ethical complications that arise in professional life are related to various obstacles that get in the way of pursuing this ideal. Additional complications arise because there are clear cases where the client is simply not autonomous. This holds for infants and young children, and therefore a professional will have to work with parent(s) or some other guardian when helping them. These cases can generate conflicts between a client’s best interests and the values and wishes of their guardian.

Put most simply, an autonomous person is self-directed. The word “autonomy” derives from the combination of the two Greek words “autos” (meaning self, or independent self) and “nomos” (meaning law or legality). The first part of the word should be familiar to everyone. Something is automatic if it is self-acting. An autobiography is a piece of writing in which someone focuses on their own life. An automobile is a vehicle whose mobility or motion is due to its own power source. Following this pattern, a person is autonomous if they have the capacity to self-regulate, that is, to govern their own behavior. In short, someone becomes autonomous once they acquire the capacity for self-determination. In this respect, autonomy is closely associated with the idea of integrity discussed in Chapter 3, because both of these depend on the capacity for self-reflection.

Put simply, people are autonomous when they are in control of their own lives, and professionals should empower their clients to be as autonomous as possible. The controlling assumption behind the fiduciary relationship is that professionals should help autonomous persons set their own life plan. To the greatest extent possible, clients should be free to live their life as they wish. For the most part, people seek help from professionals when they personally lack the specialized knowledge and skills that are needed to permit them to pursue their personal goals. A major part of the work of professionals is to give clients the information they need to deal with their specific issues.

This aspect of autonomy is captured by a traditional saying: knowledge is power. Access to expert advice empowers non-experts. Consequently, informed consent plays a central role in professional-client relationships. A client who does not understand their options is not really autonomous. An individual who does not understand their situation and the consequences of various choices is not in control of the situation. (For more on this topic, see Chapter 5.) Another implication is that professionals should provide multiple options to clients—including the option of rejecting professional help. A failure to effectively communicate options and consequences tends to result in a client’s preference for what is simply common or familiar, rather than solutions that best align with their circumstances and values.

Infants and children are not autonomous because they have not yet developed the capacity to make significant choices about their own lives. A three-year-old should not be allowed to choose their daily diet and bedtime, much less be left alone to take care of themselves without any adults present. The idea that most adults possess autonomy but no child has autonomy implies that people must develop their autonomy during the intervening years. The rebelliousness that is often attributed to adolescents is, in large part, experimentation as they develop a sense of themselves as unique individuals. In the process, many individuals will question—and sometimes abandon—the expectations and values of their family and community.

Different societies have different views about the age at which the average individual gains autonomy. Technically, this is known as “the age of majority”—that is, one is no longer a minor—and is generally aligned with the right to vote and the right to enter into legal contracts, such as taking out a student loan, signing a rental contract, or getting a personal credit card. In the United States and in most of the world, legal adulthood typically begins at 18, granting rights like voting and signing contracts. Israel uses the same rule for men, but sets the age at 17 for women.

At the same time, it is crucial to keep in mind that the concept of autonomy is not equivalent to the legal category of adulthood. Chapter 2 noted that laws can be out of alignment with moral concepts and standards. Historically, voting rights and the freedom to enter into contracts were denied to most people. For much of its history, the United States did not recognize the autonomy of women and people who were racially classified as non-White. Philosophers played an important role in developing a concept of autonomy that could be used to challenge this tradition of discrimination. Emphasizing mental capacity as the key element of autonomy, nineteenth-century English philosophers such as Mary Wollstonecraft and John Stuart Mill redefined autonomy so that it was inclusive of women, which led also to a more inclusive view about non-European peoples.

Because autonomy develops over time and with practice, client autonomy should not be approached as an all-or-none situation. The core philosophical idea is that an individual achieves autonomy when they have enough mental development, life experience, and self-control to make decisions about their own life and future. Those who develop the required capacities acquire the negative right of autonomy: other people have a duty not to interfere in their decisions about their own life. Ethically, we must respect other persons by granting them self-determination. At the same time, many clients—especially young adults—will be in a relatively early stage of developing their autonomy. Professionals have a special duty to work with these individuals to foster their autonomy, which may require extra time, effort, and patience for the professional.

Although the scope of people recognized as autonomous has expanded, not everyone above the age of 18 is autonomous. Some individuals have or develop temporary or permanent mental impairments. Thus, some people must be treated paternalistically, that is, as if they were children, with other persons acting as guardians who will make all important decisions for them. However, cognitive deficits are not the only relevant reason. Obvious examples would be convicted criminals during periods of incarceration and suspects held without bail because they are flight risks. When dealing with either children or adults with reduced autonomy, professionals will consult with, and generally require consent from, their guardians. However, professionals should make every effort to determine the preferences of even their non-autonomous clients to the degree that this is practical, and should consider those preferences when developing solutions that address the client’s needs. For example, judges generally consider a minor’s preferences when making custody arrangements, balancing preferences against what appears to be in their best interests. In social services, caseworkers should involve minors in decisions about their living arrangements or foster care placements, respecting their preferences whenever feasible.

Limits on autonomy

Autonomy is not a license to do whatever you want to do whenever you want to do it. There are important ethical limits on personal freedom. Consider these two major justifications for limiting autonomy.

The most obvious limitation concerns harm to others. There is a popular saying, “Your right to swing your arms ends just where the other man’s nose begins.” Although commonly attributed to various judges and philosophers, this saying seems to have originated in the American Prohibition Movement, as a defense of the idea that personal freedom did not give people the right of public alcohol use or public drunkenness. The community has a right to limit behaviors that pose a risk to others. Generalizing, autonomy ends when it infringes on the rights of others and where it poses a genuine risk to the community. We will see, in Chapter 6, that this idea has important consequences for professional life.

Harm to others doesn’t just mean physical harm. Someone who is renovating their home might throw a pile of scrap lumber into the alley behind their house, blocking passage through the alley. The inconvenience created for neighbors who use the alley limits their autonomy. So, this behavior violates the principle of “your right to swing your arms ends just where the other man’s nose begins” despite the absence of physical harm. Similarly, someone who steals something from a store causes economic harm to the store’s owner, and economic harm reduces autonomy. So, the prohibition against taking the property of others can be another justified limitation on freedom of action.

Second, autonomy is not simply the idea of freedom. It comes with responsibilities. It is worth noting that the original idea behind autonomy was the age of majority, which was the age at which a man could enter into binding contracts, especially financial ones. In other words, an autonomous man was one who had a duty to keep their promises. The modern concept of autonomy expands on this background tradition by recognizing that autonomy belongs to anyone with sufficient mental development and experience. Any autonomous person can make an agreement, such as making promises. However, to make a promise is to accept a duty to do something, either for another person or for society. In this way, promising involves an agreement to limit one’s future freedom. If you have a driver’s license, you got it by promising to obey the traffic laws. You’ve accepted a duty not to do various things—you won’t run red lights, you won’t exceed the speed limit, and so on.

Becoming a member of a profession also involves promising, and so limits the autonomy of each professional. This point will become important in a later section of this chapter.

4.2 Education and autonomy

Section 4.1 explained that the capacity for autonomy is regarded as the basis for both personal freedom and the various rights associated with personal liberty. On the capacity-based model of autonomy, autonomy is understood to be something that individuals gradually develop. In other words, the law may say that it happens at the stroke of midnight when you turn eighteen, but this legal rule masks the fact that mental capacities develop slowly and generally depend on practice and guided training. As explained above, the relevant capacities are mental development, life experience, and self-control.

Consequently, the capacity-based model of autonomy is bound up with one profession in a profound way. Educators play a key role in the extent to which individuals become autonomous. Historically, education’s role in supporting autonomy is the primary reason that public school educators are considered professionals. Contrary to the common view that the mission of public education is workforce preparedness, the public school system of the United States was developed with the main aim of preparing all citizens for participation in a functioning democracy. If people are going to be allowed to generate laws through a democratic process, their participation in collective self-governance depends on a grounding in personal self-governance.

Although universal public education did not yet exist, several of the founders of the United States defended it (that is, they defended education-for-all, conducted by and paid for by government). Notably, John Adams argued that placing political power in the hands of the people requires them to know “how to manage it wisely and honestly … which can be done only, to affect, in their education. The whole People must take upon themselves the education of the whole People and must be willing to bear the expenses of it.” [Letter from John Adams to John Jebb, 10 September 1785] Drawing on the lessons of history, Adams proposed that public schools are the only way to preserve democracy in the long term. This view was first put into practice on a large scale in Massachusetts in the 1830s with the work of Horace Mann, who promoted the professionalization of public-school teachers and compulsory education for all children—the latter achieved by law in 1852. In an age of increasing immigration from places that lacked democratic traditions, Mann introduced education standards and certification for teachers and promoted a curriculum aimed at “civic virtue.” In short, universal public education equips and empowers citizens. It supports and safeguards all other democratic institutions. Given the importance of the printed word as a means of sharing information and as a central vehicle for free speech in the nineteenth century, universal literacy was a key goal of Mann’s educational reforms.

Despite increasing emphasis on job and career training, the professional status of public education arises from its relationship to basic needs and how it provides a public good in relation to that need. Because the United States does not treat employment as a right of every citizen, the task of providing workforce preparation cannot be the reason that we classify education as a profession. In fact, before the development of universal public education, higher education existed almost exclusively to train specialists for professional life. This tradition of professionals who trained other professionals is another reason that education became identified as a profession.

In the same way that a client who does not see that they can pursue their own life plan is minimally autonomous, a citizen who does not understand the consequences of various political and social options is a person with minimal autonomy. Public education is dedicated to providing the development opportunities needed for this dimension of autonomy. In functioning democracies, therefore, universal public education must be funded and operated as a civic commitment. The most important skills to practice and develop are those of accessing information and thinking critically in response to it. Besides literacy (and, today, media literacy), public education should emphasize history, civics, and critical thinking. After all, a voter who is ignorant of the history of political struggles and the basics of how their government works is not in a position to make informed and autonomous choices about the direction of society.

With this in mind, the education profession faces the problem that most public education occurs before students become adults. Consequently, there is an important difference between K-12 education and college instruction. At the beginning of this process, with young children, teachers must act with high levels of paternalism. As students get older, they should be exposed to increasing levels of materials that challenge common views and values. They should be encouraged to engage in free expression, debate, and critical inquiry. At the college level, these skills should play a central role, which is why career-focused courses must be balanced against general education courses that encourage increased intellectual autonomy.

In summary, autonomy is based on mental capacities that develop over time. Trained educators have special expertise in the development of those capacities. Education at the high school level and above is an especially crucial time for exercising the key capacities and skills, and therefore this level of education demands an environment in which students develop critical thinking skills and have ongoing opportunities to exercise these skills. In practice, this generally requires exposure to, and active engagement with, views that are different from the prevailing views that dominate their social environment. An autonomous adult thinks for themselves, and the ability to do this is the result of practice. In modern society, the classroom is the forum for developing the mental habits that produce autonomous citizens.

4.3 Obstacles to the autonomy model of education

Being an autonomous person means being able to set one’s own goals, and this frequently means rejecting the expectations of family, friends, and community. Thus, a core aim of public education frequently generates conflict. As a result of efforts to make students more autonomous, educators increasingly face criticism for exposing students to controversial material and ideas that differ from those of their parents or guardians. The 21st century has witnessed a revival of non-professionals directing public school curriculum, introducing censorship into classrooms and school libraries. (The increased censorship of public library materials is a related problem.) With our increased emphasis on standardized tests and parental veto power over the lessons provided to their children, there is reason to ask if we remain committed to the vision of Horace Mann. By all measures, public school educators are less free to operate as professionals than were previous generations, and many educators feel that their professional status is being limited or even denied. The professional organization that represents them, the National Education Association (NEA), warns of the disastrous effects of recent trends.

Setting those issues to one side, public school educators face the difficult challenge of negotiating and constantly adjusting the delicate balance between their own paternalism and the gradually developing autonomy of their students. At all levels of public education, the commitment to foster student autonomy faces the obstacles of censorship, manipulation, and coercion.

The development of autonomy in personal and civic decision-making requires providing students with regular opportunities to practice key components of autonomous decision-making. First, they must practice sorting through and evaluating conflicting information, which includes evaluating the reliability of the sources of the information they encounter. Second, they must be introduced to the idea that social norms are not always right. Third, they must engage in self-reflection about their personal values in order to understand why the lifestyle choices of others might not be right for them. (These three areas are not meant to be exclusive.)

This model of education generates ethical conflicts. The educator’s duty to develop personal autonomy can create conflicts with family, friends, and the larger community. Fostering a student’s autonomy may result in their embrace of a lifestyle or mode of identity that is not be accepted, or might be judged to be morally wrong, by other people. Using the legal mechanisms of state law and local school boards, many communities and groups actively oppose exposing students to controversial topics and material. In 2022, the state of Georgia banned teaching “divisive concepts.” (The teacher’s major professional organization, the NEA, successfully overturned a similar law in New Hampshire.) But state intervention is not the only mechanism for limiting what students learn. In many places, parents have the right to review and censor material that they regard as inappropriate for their child.

What are these “divisive concepts?” Censorship most often arises concerning the topics of sex, contraceptive use, gender identity, racial identity, and the history of racial discrimination in the United States and other historical topics that are relevant to current political disagreements (e.g., civil rights, immigration policy, labor relations, and the effects of regressive taxation). Censorship extends to science classes, too. Several states attempted to ban teaching of biological evolution. So far, those bans have been ruled unconstitutional for being rooted in religious beliefs. Unable to ban it, a number of states have severely limited exposure to the topic in K-12 education. In some states, students enter higher education with little or no understanding of the core teachings of modern biology.

In summary, educational paternalism that interferes with the promotion of student autonomy arises from two external sources. First, local and state policies say that public school educators are not allowed to engage in discussion of controversial or sensitive topics. Second, some states grant parents the right to remove their children from the classroom during discussions of topics that meet with their disapproval. (In many school districts, the objection of just one parent can ban a book or educational resource for an entire school or school district.) The effect is to shelter students and reduce development of student autonomy. These interventions are paternalistic because a non-professional parent or other non-professional adults determines the degree to which students will be allowed to engage with material that could encourage them to think for themselves or develop their own personal values.

These interventions into teaching methods and curriculum undercut professional expertise. They are a rejection of the professional model of education and of the idea K-12 public educators know best how to achieve their professional goals. Furthermore, paternalistic censorship requires professional educators to become partners in manipulation. This manipulation is in conflict with the standard view that professionals have special expertise that informs the duty of care. The educational goal of developing autonomy is replaced by paternalistic manipulation.

What is meant by saying that micro-managing and silencing teachers makes them partners in manipulation? Manipulation is generally understood to be unjustified influence on someone’s beliefs and actions. Manipulation is present when one person’s beliefs and actions are shaped by information that they receive from someone else, who limits or distorts that information in order to gain that influence. In other words, manipulation succeeds because the individual does not know what it is that they do not know. In political contexts, this method of influencing people is called propaganda. In educational settings, is usually called indoctrination. By telling professional educators that they cannot teach material that they have evaluated as beneficial in education, the community rejects technical expertise. As many educators see it, these interventions de-professionalize the profession.

Unfortunately, these conflicts seem to be built into the design of American public education. There is strong agreement that people need a sense of community and cultural identity. This is normally done by raising children to respect the beliefs and values of their parents and the community that informs their social identity. However, the educational goal of promoting autonomy frequently conflicts with this norm, because promotion of autonomy requires inviting students to think about alternatives that they might pursue for themselves. Many parents do not want their offspring to become highly autonomous: they want their children to think like them and to endorse their values. On the other hand, removing material endorsed by education professionals turns schools into tools of indoctrination and manipulation, which undercuts the mission of public education in a democratic society.

In the ongoing debate about what does and does not belong in K-12 education, educational expertise is frequently attacked with the accusation that professional educators are the ones who use public education for indoctrination. This charge has been used repeatedly to justify state control over teaching materials and teaching goals. Granted, some teachers may see the classroom as an opportunity for advocacy. This happens when the personal beliefs and political values of individual educators lead them to reject the goal of promoting student autonomy. But how common is this?Accusations of this behavior are most often launched against educators on the liberal side of the political spectrum. However, there is no evidence that it is primarily or genuinely a problem of “the left.” The lack of a national database makes it difficult to provide an accurate estimate, but there are relatively few formal complaints about such behavior annually. Almost no K-12 public educators have been disciplined for such behavior. On the contrary, studies by the NEA show that roughly half of its members engage in ongoing self-censorship because they fear discipline or loss of employment by introducing ideas and material that may upset parents or the community.

Moving beyond K-12 education, issues of student autonomy and professional autonomy become more complicated in higher education. Historically, college instructors have been granted set of personal freedoms that are collectively known as academic freedom. Basically, college instructors are not required to adopt a neutral stance concerning the material they teach. They are allowed (even expected) to present and defend their own position in relation to controversial subjects within their academic subject area. Instructors may openly advocate for unpopular views. When conducting research, they are granted the freedom to research sensitive and controversial topics and to defend unpopular views.

As a positive right for teachers, academic freedom creates a negative duty for higher education administrators and oversight bodies. As employers, they should not restrict what instructors say about their field of expertise in the classroom or in their research, and employment cannot be tied to agreement or disagreement with specific viewpoints. In short, the employer cannot fire someone for being controversial. The task of determining whether a view is adequately defended should be left to peers, that is, other professionals with expertise in the same subject. At the same time, academic freedom is not a license to say do whatever one pleases. It does not extend to speech about topics that are unrelated to one’s field of study, and so it would not prevent a school from disciplining a teacher who makes racist remarks or who regularly rants about the trade deficit and tariffs in a calculus class.

Why is academic freedom permitted? A major reason is that it contributes to the process of fostering student autonomy. Because it allows instructors to advocate for ideas and discuss topics that might not be appropriate in K-12 education, it treats students as adults who are capable of engaging directly with ideas and arguments. Thus, student autonomy is expanded, not reduced, by exposure to advocacy that challenges conventional beliefs and values. An individual is not autonomous in the sense of choosing their own direction in life if they do not know how to engage with views that differ from those endorsed in their upbringing. Granted, classroom controversy and advocacy can be unsettling for some students. As inclusive, democratic institutions, colleges and universities face a major challenge when it comes to maintaining an environment for permitting the expression of controversial ideas while also providing support systems and accommodations for students who may be adversely affected by such content.

Academic freedom is sometimes criticized on the grounds that it provides immunity for educators who indoctrinate students and who manipulate students by discouraging or even suppressing opposing viewpoints. In particular, there is concern about the power of instructors to use grading to create a coercive environment. Coercion is manipulation in which a threat is introduced to gain agreement. If students feel that an instructor will punish them with a lower grade if they voice disagreement with the instructor’s position on a controversial topic, then the educational setting can quickly become one-sided and paternalistic. For this reason, an instructor who endorses or defends a specific position on a controversial topic has a duty to separate a student’s course grade from the student’s agreement of views endorsed by the instructor. It is one thing to require students to demonstrate their understanding of views and ideas they reject, but it is quite another thing to demand agreement. Higher education is not an indoctrination camp, and instructors who demand agreement are showing a lack of respect for students’ autonomy. At the same time, it is important to recognize that a student’s feeling of coercion may be misplaced. Some students are troubled by mere exposure to alternative perspectives and may confuse a legitimate requirement to accurately summarize a competing view with a coercive attempt at indoctrination.

When stereotypes influence educators

Educators are not immune from cultural biases and stereotypes, and these can lead to well-intentioned but harmful advice about which courses various students should take.

To consider a well-documented problem, a significant number of high school instructors continue to accept the cultural bias that says males are naturally better at mathematics than females. This stereotype has been proven false. There is no difference in the achievement rates of females and males who take the same classes in advanced algebra, trigonometry, pre-calculus and calculus. However, due to the stereotype, far fewer females are encouraged or advised to take these classes even if they are preparing to go to college after high school. As a result, many females find that they must spend extra time in college learning mathematical subjects that their male peers learned in high school, which delays progress toward graduation and often discourages females from majoring in subjects that require a significant math background.

When male students are encouraged to take calculus in high school but female students are not, these female students become less competitive when applying to highly selective colleges. Consequently, the biases accepted by high school educators limit or delay options for females in college, and this in turn drastically reduces the success rate for females in a number of areas, including the profession of engineering. This, in turn, must be counted as a reduction in their autonomy that arises from paternalism in high school advising and career counseling. Data suggests that similar biases are in place in many high schools with large populations of students who are not of European or Asian ancestry, where the assumption that only “Whites” and “Asians” are naturally good at math leads to a pattern of reduced course offerings in algebra, trigonometry, pre-calculus and calculus. Again, there is no documented achievement gap along these lines, but the effect of the bias is to reduce college achievement and, effectively, reducing the autonomy of the students who are steered away from advanced mathematics.

4.4 Professional education as a special case

In practical terms, respect for client autonomy is normally upheld through the professional’s adoption of value neutrality. This is does not mean the absence of governing values, because various fiduciary duties as well as the profession’s code of ethics will guide the professional’s interactions with clients. However, a professional who imposes their own values on their clients is behaving paternalistically, and doing so conflicts with the fiduciary duty.

The process of training professionals complicates the stance of value neutrality. In higher education, the students are clients. Some of them are preparing to become professionals themselves. At the same time, the professions make public statements of their ethical codes. Some students who hope to join the profession find that parts of these codes conflict with their personal values. In these cases, conflicts concerning values are likely to arise between student and instructor.

If a student plans to join a profession and is being educated for that purpose, it is appropriate to require them to endorse the ethical code governing that profession. For example, suppose a student is pursuing a degree in elementary education in Minnesota. Suppose the student believes that teachers should be free to spank an uncooperative first-grade child. Because this view is contrary to basic professional standards of elementary education, the student’s view might justify removing them from the program. Doing so would not be punishment or coercion. As explained in the discussion of integrity in Chapter 3, educators have a legitimate reason to question the integrity of a student who advocates for corporal punishment in a state that has abolished the practice.

In this way, professional education includes a screening function. Just as a student who wants to be a surgeon will be denied their goal if they repeatedly fail basic anatomy, a student who will not or cannot adopt the basic values of a profession should not be allowed to enter it. The student is a client of the education process, but value neutrality does not apply in the same way that it applies to other clients.

Here are two further examples where educators would be right to examine the values of students during their professional training.

Suppose a college senior who is majoring in social work student is doing an internship at a local shelter for people without housing, and the student refers to the clients as “animals” and frequently expresses disgust for them. At this point in the education process, the student should already know why this behavior is incompatible with the aims of social work. The internship supervisor would be fully justified in removing such a student from the internship placement, and would be justified in doing so even if it resulted in a failing grade that prevents the student from completing the degree in social work.

Or consider the widely reported case of nursing students at the University of Pennsylvania in 2019. Several students shared racist memes and language in a private social media group. The content included offensive jokes and images targeting various racial and ethnic groups. When a student reported this private behavior to school officials, the students involved faced disciplinary actions, and were given the option of suspension or mandatory sensitivity training. Why is this proper? The medical profession is committed to providing health care to everyone without bias or discrimination. Students who demonstrate resistance to these core values should not be certified in the profession, and professionals who train new members of the profession lack integrity if they endorse the professional status of students who have demonstrated that they cannot uphold these standards.

Faith-infused professional training

The explanation provided for classifying teachers as professionals cites Horace Mann and the ideals that shaped American public education. Following the expansion of civil rights in the 1960s, the goal of creating an inclusive and non-discriminatory environment has made American public education neutral about religious beliefs and values. But what about private education? Many of the most prestigious universities in the United States were founded by religious groups as private institutions. In fact, the term “professional” is derived from the idea of someone who has “professed” (publicly accepted) religious vows. Clergy were not alone in this expectation. In ancient Greece, physicians were privately trained but their tradition required new physicians to “profess” a vow to uphold a specific ethical code. In an altered form, this Hippocratic oath is used today by many medical schools. In the Middle Ages, medicine joined law and ministry as a professions demanding formal education, and then other groups gradually joined them. (Ironically, reduced expectations in the training of clergy has led to the general view that they no longer count as a profession.)

Today, a number of religiously-affiliated private institutions continue to integrate faith-based values into their curricula, often offering faith-based ethics and theology courses alongside professional training. These institutions aim to produce professionals who are not only skilled in their fields but also guided by ethical and moral principles rooted in their religious orientation. As a result, professional training at these schools may omit or reject some standard practices of professional life.

One significant example is found in the training of doctors, nurses, and other health care professionals. For example, the Roman Catholic church trains doctors at several private American medical schools. Based on their religious teaching, medical training does not extend to many standard procedures relating to reproductive health. Medical skills and knowledge relating to IVF, abortions, sterilizations, and most common contraceptives are not offered or taught due to religious beliefs.

With respect to K-12 private education, many parents send their children to faith-infused private schools because the schools will emphasize only one perspective on ethical values and controversial issues. In this respect, these schools can be seen as less committed to student autonomy than public education. In contrast, enrollment in higher education is not compulsory and students can select their own school. Because faith-based colleges and universities make no secret of their religious position, professionals trained at faith-based private institutions are understood to have given informed consent to receive training that has been tailored to the school’s religious orientation.

4.5 Refusal of Services

Generalizing from the discussion of education, professionals should not manipulate or coerce clients in order to get the client to do what the professional thinks best. Manipulation and coercion are forms of paternalism that show a lack of respect for the client. Professionals should respect and enhance the autonomy of clients who have the necessary capacities, and an important aspect of respecting client autonomy is to take appropriate steps to place the client in a position of being able to make a properly informed decision to address their needs. (Unless stated otherwise, the remainder of this chapter assumes that every client is an adult who possesses the basic capacities required for autonomy.)

In support of client autonomy, each professional is subject to the prima facie duty to provide a reasonable range of options for clients. A professional who paternalistically withholds reasonable options from clients needs a strong justification for doing so. Furthermore, each professional should work with each client to the degree needed to let the client make an informed, free choice from among these options. So, it is prima facie wrong to manipulate or coerce a client to get them to make the choice personally favored by the advising professional.

However, it would be a mistake to assume that professionals are trying to manipulate or coerce a client every time they limit a client’s choices, or even when they refuse to provide services that match a client’s preferences. A client’s wishes might not match their real needs. In other words, there are times when professional paternalism is appropriate. In these cases, the professional’s attempt to steer the client toward an appropriate choice is neither manipulative nor coercive. In some cases, professional ethics requires a professional to offer no services to a particular client in response to the client’s request.

Therefore, it is crucial to understand when professional “veto power” is appropriate, and when it is not. (This topic will be expanded in Chapter 6 in the discussion of professional complicity.)

An easy case of justified refusal of service is one where a client’s request is contrary to the standards of the profession. Helping with a client’s unjustified request turns the professional-client relationship into an agency relationship. However, client advising is not the same as customer service. Satisfying a client’s wishes is not the same thing as addressing the client’s needs. For example, an accountant has a duty to reject a client’s request to falsify a tax filing to reduce the client’s taxes, and a K-12 teacher can justifiably refuse a parent’s request to move their child to the next grade level despite child’s failure to meet the minimum achievement levels needed to move them forward.

To look at another example in greater detail, many doctors face the problem that patients demand a prescription for antibiotics when the doctor diagnoses the patient with a viral infection, such as influenza or a common cold. Antibiotics have no value in treating viral infections. Furthermore, the overuse of antibiotics creates greater immunity to antibiotics in viruses, and therefore they should not be used unless necessary. Therefore, doctors should refuse many patient requests for antibiotics. An uninsured patient may believe that the medical field is trying to “rip them off” and “make a buck” when the doctor advises them to use an expensive antiviral drug instead of an inexpensive antibiotic. However, if the patient has a viral infection, the doctor’s advice is neither manipulative, coercive, or inappropriate. If the client says they cannot afford the prescribed drug, it may be the case that the physician must stop there, advising the client that there is nothing to be done beyond rest, hydration, and over-the-counter acetaminophen (to reduce fever).

Or consider a college student who wants to graduate sooner by taking some summer courses. However, summer offerings are limited and the only course available in the student’s major is one that has a prerequisite the student has not yet fulfilled. For example, suppose the student is an economics major and sees that the required course in public finance is being taught, but the student has not taken the prerequisite course in macroeconomics. The student asks the teacher for permission to take the course. Based on past experience demonstrating that students who haven’t taken macro cannot handle core concepts of public finance, the instructor refuses the request. Clearly, both the existence of a prerequisite and the refusal to “override” it is paternalistic. Yet the paternalism is justified. When complex material builds on more basic material, sequencing is legitimate and a professionally responsible instructor will deny the wishes of the unprepared student.

To consider a more complex example, suppose that a doctor who practices family medicine is the physician for both a mother and daughter, and suppose the daughter is sixteen. The mother does not know that the daughter is sexually active and instructs the physician not to discuss the topics of sex, reproduction, and contraception with her daughter. The mother remains in the room on those occasions when the daughter has a doctor’s appointment. However, the daughter uses the health system’s online messaging service to tell the doctor that she needs to talk privately, without her mother in the room, during her annual physical exam the following week. Should the physician exclude the mother from the room during the office visit? Collectively, the medical profession recognizes sufficient autonomy in adolescent minors to grant them confidential health care for sensitive issues. The doctor should reject the wishes of the guardian (the mother) and should exclude her from the visit in order to determine why the sixteen-year-old wants confidentiality. Given the issue in this case, the physician should assist the daughter with issues relating to being sexually active even if doing so is contrary to the wishes and values of the girl’s mother.

Generalizing from these examples, there are at least four distinct reasons why a professional might legitimately reject a client’s preferences.

- A client’s preference is rejected because the profession does not recommend it as good practice.

- The individual professional rejects the client’s preference based on the specific circumstances.

- The individual professional objects to a practice or option that is endorsed by the profession and will not offer it to any client.

- A client’s preference is rejected because the client cannot pay for the service.

The doctor’s refusal to prescribe an antibiotic illustrates the first of these, as does the doctor’s rejection of the mother’s wishes concerning her adolescent daughter. The instructor’s refusal to waive the course prerequisite is an example of the second one (because the instructor might waive it for an exceptionally good student who is enrolled in macroeconomics at the same time).

The third and fourth types of cases are the most difficult ones to evaluate.

In the third case, there can be legitimate reasons for a professional to decide that a particular service or strategy should be rejected for every client despite its acceptance by the profession. For example, the novel To Kill a Mockingbird is frequently taught in American high schools—so frequently that it can be seen as a standard practice endorsed by the profession. However, some high school teachers have found that many students are offended by both its treatment of race relations in the American South and by its handling of a character with mental disabilities. They refuse to teach it, even when the school’s curriculum directs them to do so.

Although the novel was seen as progressive when published during the civil rights movement, many twenty-first century readers see that it treats Black characters too simplistically, presenting them as lacking agency and dependent on the “white savior” figure of the central male character, a lawyer. Yet another objection to the story is that the story hinges on a woman’s false accusation of sexual assault, which is troubling because the topic can be traumatic for readers who have experience such assault and because it suggests that women should not be trusted when they make an accusation of assault. Consequently, a number of teachers are openly advising other teachers to replace To Kill a Mockingbird with a more appropriate book, such as Maya Angelou’s I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings. This action can be seen as a display of integrity on their part, as a legitimate attempt to reform a practice despite its professional entrenchment.

Similarly, consider an architect who refuses to design new buildings based on the decision to specialize in architectural preservation, updating and repurposing existing buildings. There is no basis to fault this professional for turning away clients who seek a service that does not fit their thinking about the best service that an architect can provide to their community. Many lawyers are also highly specialized. A lawyer who specializes in intellectual property law may decline to help a regular client who wants their help handling a child custody case. Referring the client to another lawyer who specializes in that area is the right thing to do because it benefits the client and because it avoids putting the professional in a situation where they might not know enough to give the right advice. Finally, a Certified Financial Planner might specialize in the subfield of socially responsible investing (SRI), and will not invest client funds in companies that profit from tobacco, alcohol, gambling, fossil fuels, ultra-processed foods, and firearms. (SRI is also equated with the phrase “sustainable, responsible impact.”) Although investing in fossil fuels and gambling are common in the profession, the subfield of SRI specializes in a mode of investing tailored to a particular type of client, and a professional who acquires official certification as an SRI planner does nothing wrong to refuse service to a client who does not want to adhere to SRI goals and practices. There are plenty of others in the profession who can help them.

4.6 The professions address basic needs

Recall the example that opens Chapter 2 of this book: the pharmacist refused to provide a contraceptive product that is legal and endorsed by the profession. Is this person ethically justified in limiting services, like the SRI financial planner and the architect who only repurposes existing buildings?

These three cases are similar because they involve an individual professional’s decision to refuse certain services even though doing so is otherwise endorsed by the profession. They are also similar because they reflect the individual professional’s ethical objections to a service or option that the profession endorses. Like the teacher who selects I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings instead of To Kill a Mockingbird because the latter is racially problematic, an option is withheld based on a moral evaluation. Like the SRI financial planner, both the high school teacher and the pharmacist are in agreement that a standard option is ethically bad or has ethically troubling consequences and should no longer be presented to clients. Or, at least they themselves cannot personally condone doing so.

At the same time, the high school teacher, the architect, and the SRI financial planner fulfills their fiduciary duty (the moral duty to look out for each client’s best interests) by offering services addressing client need. However, they are also prioritizing the duty to promote the public good. In contrast to these three examples, the pharmacist who exercises conscientious objection by withholding the medication is not providing an alternative service that addresses client need.

Therefore, it would be a mistake to simply fault any professional who paternalistically eliminates certain options. The situation is more complex than that. Different professionals will make different judgments about what is best, and ethical considerations can motivate a professional to break away from standard practices. Dissent of this kind can be evidence of professional integrity.

Yet it would be a mistake to go the other extreme of saying that every professional has a right to refuse any services to any person for any reason. If there are no limitations on refusal of service based on conscientious objection, then the fiduciary duty is meaningless. The professions address basic needs, and clients count on the profession to provide services addressing their needs.

So how does the refusing pharmacist differ from the Certified Financial Planner refuses to invest client funds in specific areas or the attorney who will not handle a child custody case?

The most obvious difference is that this pharmacist was not set up as a specialized pharmacy. There are two sorts of these, but this was neither. One type is the compounding pharmacy dedicated to mixing unique drugs for patients who do not respond to standard drug preparations. They do not carry standard units of drugs for purchase. However, that is a highly specialized service, not a refusal of service. The second type is a pharmacy affiliated with a faith-based hospital, such as the pharmacy within a Roman Catholic hospital. They do not provide contraceptives to anyone. So they are unlike the lone pharmacist making an individual decision about who gets access when it is their time to work. The public expects pharmacists in ordinary pharmacies to provide any and all drugs that have been tested and approved through medical research. Many drugs are restricted by prescription to ensure that they are only administered to appropriate patients, but the idea that a standard, approved drug should not be supplied for its intended purpose runs contrary to the public’s legitimate expectation about this profession.

Public expectation is important here. The professions are permitted to monopolize and restrict access to an area of essential service because the profession promises that, in return, they will ensure high standards of service in meeting public demand for their help. The professions have entered into a social contract in which they promise the public that everyone who seeks help will receive competence and integrity from every professional they encounter. Therefore, an individual professional who will not conform to legitimate expectations of the public is failing to fulfill their prima facie duties to serve the public. (The idea of prima facie duties is explained in Chapter 2.) Professionals assume their duties by virtue of having entered the profession, and to enter the profession and then reject what is expected of professionals is not the behavior of a person of integrity.

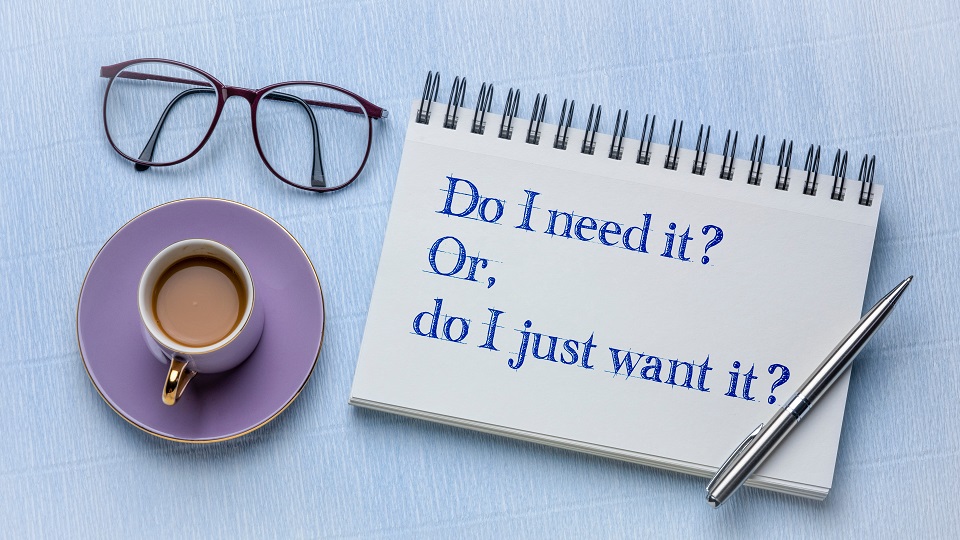

It is crucial to remember that what a client needs and what a client wants are not always the same. Professional duty applies to needs. Furthermore, there is often more than one way to address a need. To Kill a Mockingbird with I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings both address the needs of students (and, arguably, the latter does so in a better way). So, a teacher who selects the latter is not refusing to address students’ needs. But if a woman needs an emergency contraceptive, then that is what she needs. There is no substitute. The pharmacist who appeals to conscientious objection in refusing to provide it is denying responsibility to address a client’s needs. So, it is unlike the case where a professional is willing to address needs while rejecting a specific preference.

Therefore, to better understand when a professional lacks integrity in refusing to provide a service or option, more must be said about professionals as experts who provide the public good of addressing basic needs. The different professions address different basic needs in cases where current knowledge or social organization has resulted in a requirement of advanced knowledge and training for those who provide services addressing that need.

- Medicine, including pharmacy services, address the basic need of health. In addition to this core task, pharmacists often provide services that are only indirectly related to health (such as providing cosmetics that are safe to use) and even ones that can be contrary to health (such as selling candy). They have no duty to sell these products.

- Counseling specializes in the sub-field of mental health, often with attention to the related issue of social interactions.

- Social work addresses the reality that we have needs as social creatures, and human flourishing demands a healthy society and healthy social interactions. Frequently, social workers identify and address social dynamics and dysfunctions that harm individuals or reduce their capacity to flourish.

- The core task of educators is to direct and support intellectual and personal development. Job training and career preparation are specialized sub-fields of education rather than its core purpose. The trend in providing free meals to students in K-12 public schools might seem to be similar to a pharmacy selling cosmetics, but that is not really the case. Hungry students who do not have access to nutritious food cannot learn, and so providing nutritious meals is not incidental to fulfilling their purpose.

- The core task of the accounting profession is to inform the public of the financial stability of businesses, with a related task of providing individuals and businesses with advice about their financial status, such as what they owe annually in taxes.

- The core task of professional financial planners—those who work with clients using the fiduciary model—is to secure the long-term financial stability of clients.

Given that the professions are defined by the needs they address, and given that the professions have a favored and protected status in return for addressing these needs, there is no professional obligation to help someone if what they seek is not aligned with the basic need(s) addressed by that profession.

If a client finds that the local pharmacy does not stock their favorite shampoo or candy, they may be disappointed. However, they have no moral complaint against the pharmacy, for these things are not directly related to the core task and basic need that distinguishes that profession from others.

Similarly, some parents might be unhappy that their local high school has replaced To Kill a Mockingbird with I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings, or there may be parents who are angry because the school district cut funding for the theater program or Inter-mural golf, but these specific options are not essential to the goal of education. There are simply too many options to provide them all. So long as the arts and athletics are available to all students, preferably with some options that meet different preferences, parents and students have no grounds to complain that their favored option is excluded. This is especially true if their favored option tends to create discriminatory or exclusionary barriers. (Public high schools with their own golf course are basically unknown, and many families cannot afford the fees charged by golf courses, resulting in a sport that has a built-in barrier to general participation.)

The story is different when a particular pharmacist refuses to provide morning-after or “Plan-B” contraception, or the pharmacy refuses to stock it. These decisions contradict the core task of the pharmacy profession. The basic facts are indisputable: pregnancy creates far higher health risks than these contraceptives, and an individual who wants to use the drug to avoid pregnancy has made a decision that is consistent with the health mission of the pharmacy. Given that any other option for a woman in this situation places a greater burden on her health than using “Plan B,” the pharmacist who is looking out for her best interests should assist her. Sometimes an objection is raised along the lines of saying that the activity of consensual sex implies acceptance of pregnancy, but this objection violates the core idea that professionals should help unless doing so is clearly unethical. Refusing to provide “Pan B” for this reason would be like an emergency room doctor refusing to help a skier with a broken ankle because the skier assumed the risk of it by skiing. The immediate task of a professional is to address a client’s problems and needs, not to judge their life and reform them.

Still, some individual professionals hold that certain common solutions for clients’ problems are simply unethical. For example, many physicians will not perform abortions. They feel that they cannot, in good conscience, provide these services. What then?

4.7 Recuse and refer

There is a standard position on this situation, captured by the phrase “recuse and refer.” To recuse oneself is to withdraw one’s services for a legitimate reason. When a professional wishes to recuse themselves from addressing a request for help in addressing a need that falls within the profession’s defining area of expertise, that professional has a duty to refer the case to a professional who will provide for the client. (Note, again, the importance of distinguishing a client’s needs from a client’s personal preferences, desires, or wishes.)

There are states that say pharmacists do not have a legal duty to refer a person in need to another professional. However, legality is not morality, and it is difficult to locate any moral objection to requiring referral as part of any recusal. The most common argument is that a religious-based ethical recusal must be honored, and this is the line of argument that has been used to create state laws that permit recusal without requiring referral. However, it is hard to see why recusal without referral on religious grounds should be the allowed of professionals who have voluntarily pledged to provide service in a religiously pluralistic society.

Finally, a professional who recuses but does not refer is unjust. While many individuals can locate a different professional to help them, many others face barriers and a recusal will have the practical effect of simply denying them services. For example, many parts of the country are “pharmacy deserts,” that is, areas where the nearest pharmacy is ten or more miles away. (This would be a distance where even a healthy person would be unlikely to reach a pharmacy by walking there if they lacked a car or public transportation.)

The problem is becoming increasingly severe in rural areas with scattered population. A recusal and referral can have the effect of unfairly burdening or denying services to low-income clients, people with mobility issues and limited resources, and others (e.g., adolescent minors) who face obstacles in traveling any distance for services. To be clear, the problem of service deserts is not just an issue with pharmacies. It holds for many professional services. For example, cardiovascular disease is a prevalent chronic disease and a major cause of death, yet about half of U.S. counties have not a single cardiologist in that county to address cardiovascular issues. Rural counties also have difficulty attracting K-12 teachers in such areas as mathematics, special education, and science. There is also an extreme shortage of attorneys in rural America.

In an urban or suburban setting where another pharmacy is two blocks away, recusal and referral is generally sufficient to meet the professional’s basic duty of care. However, professionals have an ethical duty to provide for needs relating to the profession’s core purpose and professionals should not abandon a client in need. Recusal is unethical if it amounts, in practice, to a denial of relevant services normally available from the profession.

In conclusion, recusal and referral will be an immoral violation of duty in either of two situations. First, it is a violation of duty if it places an impractical obstacle on the client (as in the Chapter 2 example of the woman in Minnesota seeking a “Plan B” contraceptive). Second, referral is wrong when it creates an obstacle or unjust burden for a disadvantaged client. (An example would be a professional referring a client who relies on a wheelchair to a provider located in the upper floor of an older building that does not have an elevator.) Recusal is attached to a duty of genuine referral, where one professional can anticipate successful transfer of the case to someone who will provide the appropriate services. The exceptions are service providers that are too specialized to address a particular need, or which have a clear, strict, and publicly-known policy of not providing a particular service.

4.8 Costs and the duty to the public

The discussion of recusal and referral observed that the expense of professional services can be a barrier to receiving those services. As a result, most people will never establish a professional-client relationship with an architect, accountant, engineer, or professional financial planner. Most people will consult with a lawyer only once or twice in their lifetime. Many will never work with a mental health counselor or social worker. How can this be the case, if professionals address basic needs? How basic are these needs if most people have little or no interaction with most professions?

On the one hand, many people receive some of these services indirectly. They benefit daily from the social improvements and increased safety that is created by engineers, architects, accountants, social workers, lawyers, and public health professionals.

On the other hand, when the cost of a service blocks access for a large number of people whose life choices and opportunities are then reduced, the profession does not fulfill its promise to provide the public good that they address. This is especially troubling where a profession has a monopoly or near-monopoly on providing those services.

Although relatively few people plan to build their own home under the guidance of an architect, almost everyone would benefit from affordable access to dentists, lawyers, accountants, and certified financial planners. Furthermore, when high costs block services, this is done because it is in the interests of the profession and its members, rather than because a professional judges it to be in a client’s best interests. Finally, an inability to receive professional services when needed will frequently result in a loss of autonomy on the part of the person who needs professional help. An untreated chronic disease or loss of one’s home because one has not received proper advice in financial planning are two of countless ways that lack of access can put a halt to the pursuit of one’s goals. Put bluntly, the high cost of many professional services means that wealthier people are more likely to have their needs met, giving them greater autonomy than poorer people. (See also Chapter 7, on justice.)

In summary, it is unfortunate that a “business” or “sales” model of professional services is frequently used to undercut the principle that the professions have a duty of care toward everyone, rich and poor alike. Many professional services are treated more like expensive private benefits for purchase, undercutting the pledge to provide a public good. However, the relationship that holds between professional and client is supposed to be very different from the one that holds between a business and a customer. A shoe store does nothing wrong in refusing to give free shoes to someone who is barefoot and poor, but a hospital does something very wrong if its emergency room refuses to treat a gunshot victim who has no health insurance and who appears unable to pay for services. And what is true in health care is true of other professions, too.

The problem of service denial extends to many not-for-profit professional institutions, such as hospitals and a number of prestigious private universities. Non-profits receive significant financial advantages for promising to prioritize public benefit. Rather than use this advantage to reduce the cost of services, many nonprofits charge more than enough to generate significant profits. They are called “non-profit” only because they do not distribute these earnings to owners and shareholders. Increasingly, non-profits use their excess funds to expand, monopolizing more of a local or regional market and buying up or eliminating alternative providers. As a result, many economists think that non-profit institutions drive up the cost of professional services instead of reducing them.

Generalizing, there is a basic failure of justice in the practice of denying professional services to people with limited funds. The high cost of many professional services blocks access to services that are designed to be a public good. Thus, the pay-as-you-go model is discriminatory. There is also a question of integrity. The professions state that their work is a public service and that they are committed to societal well-being. This pledge is clearly inconsistent with practices that leave many people without genuine access to their expertise.

In passing, it should be noted that the duty to help cannot be restricted to those who are already established clients. As public goods, the professions are obligated to serve the public, meaning all of the public. Thus, there is a prima facie duty reach out to people who do not approach professionals due to the cost.

Recognizing these problems, a number of professions require their members to do pro bono work, that is, to donate some of their time by providing free professional services. The term “pro bono” is short for “pro bono publico,” which is a Latin phrase meaning “for the public good.” Among the professions, law is probably best known for doing pro bono work. The American Bar Association (ABA) recommends that lawyers perform at least one hour of pro bono service per week. However, this is not an enforced requirement. In practice, this means offering free legal representation or advice to a small number of low-income clients, non-profit organizations, or underrepresented communities. At the state level, some bar associations and legal societies require some annual amount of pro bono work. However, pro bono work is not limited to the legal profession. Many medical professionals, including doctors, nurses, and dentists, donate some time annually to working in free clinics that address under-served populations. Architects and engineers often contribute their expertise to community development projects. Many accountants offer their skills to help small non-profits with financial planning and tax preparation, or donate time to free clinics that help lower income people with tax issues.

Despite these efforts, all professions currently fall short of addressing the full needs of society.

Let’s assume that more radical changes would be difficult to make. It is unlikely that American law will step in to solve the problem. For example, there is legal standard for the medical profession, but it is a weak one. The Emergency Medical Treatment & Labor Act (EMTALA) requires Medicare-participating hospital emergency departments to provide access to stabilizing treatment, regardless of ability to pay. (In response, some smaller hospitals have simply closed their emergency departments.) This means that about 30% of U.S. hospitals are not required to offer assistance under this law. Furthermore, the rule is restricted to helping those who health is in “serious jeopardy.” There are countless serious needs that fall short of this standard. So, the strongest requirement that is currently in place in the United States is actually relatively weak. The other professions do even less to address the needs they promise to serve.

Because the government will not hold the professions accountable for addressing needs, the professions have a duty to set higher standards for their members, requiring professionals to provide substantially more pro bono work. Excusing refusal of service by appealing to a business model is not consistent with the idea that professionals have special duties and should aim to uphold a fiduciary relationship with clients. Car dealerships, grocery stores, and the smartphone industry are not expected to prioritize the best interests of customers, and this is why they have “customers” rather than “clients.” Clients for professional services are often customers (i.e., persons who purchase goods and services), but the professions say that they are something more than customers.

4.9 Resistance to additional pro bono work

The expectation of pro bono service is often challenged by appeal to economics. The argument claims that free markets are the best way to distribute resources, or they contend that professionals cannot “stay in business” if they offer free services to large numbers of non-paying clients.

However, these defenses of limiting services for the poor assume that a business model of the professions must be preserved, and that it is right to market and sell professional services on the open market for whatever economically-secure people are willing to pay. (See also Chapter 7, Section 7.4.) In other words, the argument presupposes a commercial model in which professionals are equated with businesses that sell products, and professional services are simply a product for sale, and no different from fast food burgers and shoes.

However, the assumption that the business model is best is undercut by three practices.

- The United States has already accepted that many public goods should be funded with tax revenues instead of personal payments by individual users. Think of law enforcement, public roads and highways and bridges, parks and playgrounds, public libraries, and the subsidized public transportation systems of many cities.

- The United States already promises to meet the basic needs of financial security and health for older citizens by providing Social Security and Medicare. Supplement this aid with the most successful government-funded professional service in our history: free public K-12 education for everyone, citizen and non-citizen resident alike. In short, government already provides considerable free access to public goods and professional expertise for younger and older people.

- Beyond direct government funding, the common use of not-for-profit status in such areas as health care, higher education, and social work demonstrate that we already recognize the value of an alternative to free-market capitalism.

Another powerful reason to endorse government support of the professions is the failure of the business model to provide enough professionals who choose to provide services in key areas. When professions are treated as jobs like other jobs, they have customers rather than clients. Income depends on what customers can and will pay. At the same time, a business model has been imposed on higher education, saying that individual professionals are responsible for the bulk of the costs of their advanced education. In recent decades, state and federal governments have reduced financial support for advanced education. The older tradition of free public college has been replaced by a system in which most of the costs are paid by students. (See Chapter 7, Section 7.5.) Consequently, most college students who become professionals take on loan debt, and this debt burden is often substantial.

Consequently, the result has been a steady drop of doctors who specialize in lower-paying areas of medicine, such a pediatrics and endocrinology. Facing debt and seeing where the opportunity lies, there are fewer and fewer pediatricians, geriatricians, and endocrinologists relative to the demand. Normally, this would increase their wages, because low supply plus high demand translates into higher prices. However, medicine doesn’t fit the standard pattern, because disease often correlates with poverty. The United States has especially high levels of poverty for families with children and people with diabetes, so revenue is low despite the demand. Geriatrics, the specialization of caring for the elderly, is a low-income field of specialization because Medicare caps reimbursement to control costs for seniors. Meanwhile, there are high profits for specializations that cater to wealthier people. For example, medical dermatologists who specialize in skin cancers are in short supply, but there is an oversupply of physicians who provide cosmetic dermatology. A similar pattern plays out with institutions: rural hospitals close at an alarming rate because they serve a sparse, poorer population. In the absence of strong government intervention to stabilize the system, more and more people will experience health desserts and the rationing of health care. The problem is made worse by a business model, not better.

Still, many people oppose “socialism” and the “socialization” of professional services on the model of free public schools. In order to uphold the principle that clients are not mere customers, the obvious solution is to put the burden of responsibility on the economic beneficiaries of the current system, namely, professionals who sell their services directly to the public. Working collectively, they have monopolized control of these services in exchange for the promise of meeting society’s needs. They therefore owe those services to those who need them. We can set aside professionals who are government employees, because their work is already structured as public service. However, all other professionals owe the public a substantial amount of pro bono work, many times more than professional groups currently suggest as the annual goal.

To clarify the point just made, need must always be distinguished from wishes and wants. Many professionals sell their expertise by offering services that go beyond basic need. Consequently, their work is not covered by the pledge to use their expertise to provide for society’s needs. Many professions would be better able to serve real, persistent needs by limiting the training and licensing of professionals who offer inessential services. A strong case can be made, for example, that dermatologists should be licensed on the condition that they will not make appointments for “vanity” care clients if it means a delay for patients with medical conditions. The American Academy of Dermatology (AAD) should require its members to pledge that they will not schedule clients for elective cosmetic procedures (e.g., cosmetic treatment of age spots) if it delays anyone’s service for medically necessary dermatology, and the AAD should police adherence to this pledge. Needs should be prioritized over wants.

Transporting the same issue from medicine to education, children need regular exercise, but this does not mean that every school has an obligation to offer every imaginable sport to those who desire them. No public school district can afford to fund all the coaches and facilities needed to be sure that every junior high school student has access to ice hockey, golf, lacrosse, bowling, diving, equestrian (horse riding), skiing, and rowing. The educational duty is fulfilled if there are several options, including options that are suitable for students with disabilities. Similarly, the proposal that everyone has a right to legal services when needed (beyond the current guarantee of a public defender if one is charged with a crime), does not mean that everyone has a right to free legal help because they wish to file a frivolous lawsuit about the ugly color the neighbor paints their house.

The position presented here is that every profession has a duty to provide a decent minimal level of service to everyone who needs their services, regardless of their ability to pay. However, the professional organizations have done a poor job of seeing that this happens. But this does not absolve individual professionals of a prima facie duty to address needs. To combine this point with the previous discussion of recusal and referral, it is difficult to avoid the conclusion that individual professionals have a prima facie duty of extensive pro bono service in relation to the core needs they have pledge to address. In particular, it is a violation of professional duty to reject, as a client, an individual for merely economic reasons when that person has a strong need for those services. Thus, an individual professional in a “service desert” where there are few other options might carry a higher burden of pro bono work than one who lives where there is a higher concentration of professionals. Professional life is public service, not merely a job or business.

4.10 Chapter Summary